Avon Local History & Archaeology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stanton Drew 2010 Geophysical Survey and Other Archaeological Investigations

Stanton Drew 2010 Geophysical survey and other archaeological investigations John Oswin and John Richards, Bath and Camerton Archaeological Society Richard Sermon, Archaeological Officer, Bath and North-East Somerset (BANES) Bath and North-East Somerset (BANES) www.bathnes.gov.uk Bath and Camerton Archaeological Society www.bacas.org.uk Stanton Drew 2010 Geophysical survey and other archaeological investigations John Oswin and John Richards, Bath and Camerton Archaeological Society Richard Sermon, Archaeological Officer, Bath and North-East Somerset (BANES) With contributions from Vince Simmonds Bath and North-East Somerset (BANES) www.bathnes.gov.uk Bath and Camerton Archaeological Society www.bacas.org.uk Report compiled by Jude Harris Stanton Drew i The surveys were carried out under English Heritage licences, SAM numbers 22856, 22861, 22862 and BA44 © Bath and Camerton Archaeological Society 2011. Stanton Drew ii Abstract Bath and Camerton Archaeological Society undertook geophysical and other surveys at the stone circles at Stanton Drew, Bath and North East Somerset (BANES), between May and September 2010, in collaboration with the BANES archaeologist, Richard Sermon. The surveys were intended to enhance the knowledge gained by the work carried out the previous year. The completion of a high data density magnetometer survey over the whole of Stone Close has added much extra detail, including a new henge entrance, posthole settings and an area of activity just outside the circle to the south-east. Use of resistance pseudosection profiles, together with an increased area of twin-probe resistance, has given a greater understanding of the underlying geology as well as sub-surface features. In the SSW Circle, an EDM survey has shown how the circle was positioned very deliberately to occupy the small flat plateau, with views northwards across the other circles towards the River Chew, westwards to the Cove, and across the valleys to the south and east. -

Bristol Open Doors Day Guide 2017

BRING ON BRISTOL’S BIGGEST BOLDEST FREE FESTIVAL EXPLORE THE CITY 7-10 SEPTEMBER 2017 WWW.BRISTOLDOORSOPENDAY.ORG.UK PRODUCED BY WELCOME PLANNING YOUR VISIT Welcome to Bristol’s annual celebration of This year our expanded festival takes place over four days, across all areas of the city. architecture, history and culture. Explore fascinating Not everything is available every day but there are a wide variety of venues and activities buildings, join guided tours, listen to inspiring talks, to choose from, whether you want to spend a morning browsing or plan a weekend and enjoy a range of creative events and activities, expedition. Please take some time to read the brochure, note the various opening times, completely free of charge. review any safety restrictions, and check which venues require pre-booking. Bristol Doors Open Days is supported by Historic England and National Lottery players through the BOOKING TICKETS Heritage Lottery Fund. It is presented in association Many of our venues are available to drop in, but for some you will need to book in advance. with Heritage Open Days, England’s largest heritage To book free tickets for venues that require pre-booking please go to our website. We are festival, which attracts over 3 million visitors unable to take bookings by telephone or email. Help with accessing the internet is available nationwide. Since 2014 Bristol Doors Open Days has from your local library, Tourist Information Centre or the Architecture Centre during gallery been co-ordinated by the Architecture Centre, an opening hours. independent charitable organisation that inspires, Ticket link: www.bristoldoorsopenday.org.uk informs and involves people in shaping better buildings and places. -

November 2014 20P

November 2014 20p United Benefice of Publow with Pensford, Compton Dando and Chelwood Parish News Tool Hire - Diggers & Dumpers - Toilet Hire 01225 331669 www.alidehire.co.uk are proud to sponsor the local Parish News United Benefice of Publow with Pensford, Leaves from the Rector’s Diary Compton Dando and Chelwood 19 September 27 September There is one little ceremony which has become After I had dedicated the new organ at Publow, Rector quite popular during the past few years - Peter King shook the dust out of it, and the bats Revd Canon John Simpson The Rectory, Old Rd, Pensford 01761 490221 thanksgiving for Marriage. Today a couple came from the rafters, in an invigorating organ recital. Reader to Publow where they had married fifty years There was a good and appreciative audience. Mrs Noreen Busby 01761 452939 ago - same day, same time. We have a homely 28 September little service to offer, and it is a joy to share in Church wardens people’s rejoicing in this way. We sent out 50 invitations to couples who had Publow with Pensford Mr Andrew Hillman 01761 490324 been married in the Benefice since I arrived, for Mrs Janet Smith 01761 490584 24 September a Marriage Thanksgiving Service at St Mary’s Compton Dando Mr David Brunskill 01761 490449 We must stop calling him “the new bishop” this morning. We usually make good contact for Peter of Bath and Wells has been with us with couples before their weddings, but often Mrs Fiona Gregg-Smith 01761 490323 in Somerset since the beginning of June, and little afterwards. -

Clifton & Hotwells Character Appraisal

Conservation Area 5 Clifton & Hotwells Character Appraisal & Management Proposals June 2010 www.bristol.gov.uk/conservation Prepared by: With special thanks to: City Design Group Clifton and Hotwells Improvement Society Bristol City Council Brunel House St. Georges Road Bristol BS1 5UY www.bristol.gov.uk/conservation June 2010 CLIFTON & HOTWELLS CONTENTSCharacter Appraisal 1. INTRODUCTION P. 1 2. PLANNING POLICY CONTEXT P. 1 3. LOCATION & SETTING P. 2 4. SUMMARY OF CHARACTER & SPECIAL INTEREST P. 4 5. HisTORIC DEVELOPMENT & ARCHAEOLOGY P. 5 6. SPATIAL ANALYSIS 6.1 Streets & Spaces P. 14 6.2 Views P. 17 6.3 Landmark Buildings P. 21 7. CHARACTER ANALYSIS 7.1 Overview & Character Areas P. 24 7.1.1 Character Area 1: Pembroke Road P. 27 7.1.2 Character Area 2: The Zoo & College P. 31 7.1.3 Character Area 3: The Promenade P. 34 7.1.4 Character Area 4: Clifton Park P. 37 7.1.5 Character Area 5: Victoria Square & Queens Road P. 41 7.1.6 Character Area 6: Clifton Green P. 44 7.1.7 Character Area 7: Clifton Wood Slopes P. 48 7.1.8 Character Area 8: Clifton Spa Terraces P. 50 7.1.9 Character Area 9: Hotwells P. 55 7.2 Architectural Details P. 58 7.3 Townscape Details P. 62 7.4 Materials P. 67 7.5 Building Types P. 68 7.9 Landscape & Trees P. 70 8. TYPICAL LAND USE & SUMMARY OF ISSUES 8.1 Overview P. 73 8.2 Residential P. 73 8.3 Institutions & Churches P. 74 8.4 Open Spaces & Community Gardens P. -

The Wickets, Sandy Lane, Stanton Drew BS39 4EL

Non-printing text ignore if visible The Wickets, Sandy Lane, Stanton Drew BS39 4EL Non-printing text ignore if visible The Wickets , Sandy Lane, Stanton Drew, BS39 4EL Price: £545,000 A detached family home Large sitting room with feature fireplace Brilliant village location Master bedroom with ensuite Boasting countryside views Double garage and off street car parking DESCRIPTION Set along a quiet country lane this detached family home benefits from deceptively spacious Chew Valley is unique in the West Country, comprising some thirty five thousand acres of accommodation, pleasant countryside views and has only ever had one owner since new! The unspoilt and protected countryside which occupies the middle ground of the Bath, Bristol and property is positioned within the heart of Stanton Drew, just a stones throw from the village Wells triangle. Dominating the scene are the Chew Valley and Blagdon Lakes, notable for their Pub, Primary School and Village Hall. The village position is also bound to suit the commuter as fishing, birdlife, sailing and nature study amenities. The villages in the Valley are all unspoilt and the property sits almost equidistant from Bristol, Bath & Wells. each has its individual charm and character. Only seven miles to the north of the Chew Valley is the City of Bristol, the West Country's financial and business centre, whilst the charming City of The property itself is entered at the front through a porch straight into a large entrance hall. Bath with its Roman origins and Georgian architectural masterpieces is under half an hour's The downstairs accommodation includes; a large sitting room with a feature fireplace and drive to the East. -

Bristol's Urban Farm?

BRISTOL FOOD NETWORK Bristol’s local food update2012 community project news · courses · publications · events january–february If you’re one of those people who’ll start out 2012 with good intentions, then you may like to add one or two of these suggestions to your resolutions... But if you just love local food, then you may like to try them anyway! 1. I’ll shop on a high street in a part of the city that I don’t know very well. 2. I’ll try out a market or food event that I haven’t been to before 3. I’ll try some local produce that I haven’t tried before. 4. I’ll grow something new. 5. I’ll ask where my food has come from. Please email any suggestions for content of the March–April newsletter to [email protected] by 10 February. Events, courses listings and appeals can now be updated at any time on our website www.bristolfoodnetwork.org Bristol’s urban farm? Keith Cowling Since the article I wrote on ‘Farming the suggested that some form of short term City’ in the September/October issue of agricultural use that does not involve a lot Bristol’s local food update, a very large of public and vehicular access would be Bristol’s local food update is produced (overwhelming possibly) opportunity worth considering (the first thought was by the Bristol Food Network, with support has emerged to trial urban agriculture in growing biomass, such as miscanthus!!!). from Bristol City Council. Bristol on a significant scale. As many The Bristol Food Network is an umbrella This is a huge central site of about 2.5 of you already know, Bristol City Council group, made up of individuals, hectares with little overshadowing and community projects, organisations has been facilitating discussions on a source of river water. -

Notfoprint21.Pdf

2011 Lake Odyssey was a Heritage Lottery Funded project exploring local history through the arts with a particular focus on the 1950’s, when Chew Valley Lake was made. This was a major local event. The town of Moreton was fl ooded to make way for a reservoir supplying water to South Bristol and the Queen visited the area to offi cially open and inaugurate the lake in 1956. The Lake Odyssey 2011 project gave pupils at Chew Valley School and their cluster of primary schools a chance to explore the history of their community in a fun and creative way. Pupils took part in various workshops throughout the spring and summer of 2011 to produce the content for the fi nal Lake Odyssey event day on Saturday 16th July 2011, which saw the local community come together for a day of celebration and performance at Chew Valley Lake. Balloon Launch The Lake Odyssey 2011 project offi cially launched on Friday 4th March with a balloon re- lease. Year seven and eight pupils released the balloons to mark and celebrate the occasion. A logo competition had been running within the primary cluster and Chew Valley School to fi nd a design for the Lake Odyssey logo. The winners were announced by Heritage Lottery representative Cherry Ann Knott. The lucky winners were Bea Tucker from East Harptree Pri- mary School and Hazel Stockwell-Cooke from Chew Valley School, whose designs featured in all publicity for the Lake Odyssey 2011 project. Bishop Sutton Songwriting Swallow class from Bishop Sutton Primary School took part in a song writing workshop, com- posing their own song from scratch with Leo Holloway. -

Sat 14Th and Sun 15Th October 2017 10Am To

CHEW VALLEY BLAGDON BLAGDON AND RICKFORD RISE, BURRINGTON VENUE ADDRESSES www.chewvalleyartstrail.co.uk To Bishopsworth & Bristol Sarah Jarrett-Kerr Venue 24 Venue 11 - The Pelican Inn, 10 South Margaret Anstee Venue 23 Dundry Paintings, mixed media and prints Book-binding Parade, Chew Magna. BS40 8SL North Somerset T: 01761 462529 T: 01761 462543 Venue 12 - Bridge House, Streamside, E: [email protected] E: [email protected] Chew Magna. BS40 8RQ Felton Winford Heights 2 The art of seeing means everything. The wonderful heft and feel of leather To A37 119 7 Landscape and nature, my inspiration. bound books and journals. Venue 13 - Longchalks, The Chalks, Bristol International Pensford B3130 3 & Keynsham Chew Magna. BS40 8SN Airport 149Winford Upton Lane Suzanne Bowerman Venue 23 Jeff Martin Venue 25 Sat 14th and Sun 15th Venue 14 - Chew Magna Baptist Chapel, Norton Hawkfield Belluton Paintings Watercolour painting A38 T: 01761 462809 Tunbridge Road, Chew Magna. BS40 8SP B3130 October 2017 T: 0739 9457211 Winford Road B3130 E: [email protected] E: [email protected] Venue 15 - Stanton Drew Parish Hall, Sandy 192 13 1S95tanton Drew Colourful, atmospheric paintings in a To Weston-Super-Mare 17 An eclectic mix of subjects - landscapes, 5 11 16 10am to 6pm variety of subjects and mediums. Lane, Stanton Drew. BS39 4EL or Motorway South West 194 seascapes, butterflies, birds and still life. Regil Chew Magna CV School Venue 16 - The Druid's Arms, 10 Bromley Stanton Wick Chris Burton Venue 23 Upper Strode Chew Stoke 8 VENUE ADDRESSES Road, Stanton Drew. BS39 4EJ 199 Paintings 6 Denny Lane To Bath T: 07721 336107 Venue 1 - Ivy Cottage, Venue 17 - Alma House, Stanton Drew, (near A368 E: [email protected] 50A Stanshalls Lane, Felton. -

Chew Magna and Stanton Drew

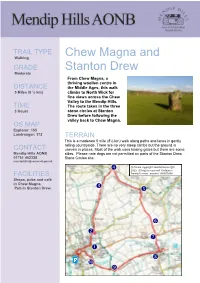

TRAIL TYPE Chew Magna and Walking GRADE Stanton Drew Moderate From Chew Magna, a thriving woollen centre in DISTANCE the Middle Ages, this walk 5 Miles (8 ½ km) climbs to North Wick for fine views across the Chew Valley to the Mendip Hills. TIME The route takes in the three 3 Hours stone circles at Stanton Drew before following the valley back to Chew Magna. OS MAP Explorer: 155 Landranger: 172 TERRAIN This is a moderate 5 mile (8½ km) walk along paths and lanes in gently rolling countryside. There are no very steep climbs but the ground is CONTACT uneven in places. Most of the walk uses kissing gates but there are some Mendip Hills AONB stiles. Please note dogs are not permitted on parts of the Stanton Drew 01761 462338 Stone Circles site. [email protected] © Crown copyright and database right 2015. All rights reserved. Ordnance Survey License number 100052600 FACILITIES Shops, pubs and café in Chew Magna. Pub in Stanton Drew. DIRECTIONS AND INFORMATION START/END Free car park in the Turn left out of the car park then turn right by the co-op. Take the centre of Chew Magna first right and walk along Silver Street. Grid ref: ST576631 (1) At a T-junction turn left and follow the road uphill, stay on the HOW TO road as it bends to the right passing a footpath sign on the left. GET THERE (2) At the next right bend take a signed footpath on the left, going up some steps to a metal kissing gate, then go uphill across a BY BIKE field to another metal kissing gate. -

Stanton Drew Parish: Environment and Landscape Character Assessment

Stanton Drew Parish: Environment and Landscape Character Assessment Page 1 of 8 Stanton Drew Parish: Environment and Landscape Character Assessment Stanton Drew parish is set in an undulating environment of mainly grassland and arable farmland containing a variety of habitats including woodlands, hedgerows, mixed flora verges, a river, riparian corridor and a floodplain. Official Designations: Area 2: Chew Valley Green Belt: the Green Belt washes completely over the entire parish Conservation Area: encompassing much of the main residential area near river and church SNCI: one follows the course of the River Chew in the northern sector of the parish another, the Pensford Complex, lies on the western boundary of the Parish and which is a known habitat for European Protected Species. Character Summary Stanton Drew Parish is located approximately nine miles south of Bristol and two miles east of Chew Magna on the southern side of the River Chew, in gently sloping and undulating countryside. The landscape of Stanton Drew Parish is predominantly rural agricultural, with ancient artefacts. In the recent past the Parish was heavily dependent on coal mining, the Pensford Colliery workings having closed down in 1959. The settlements within the Parish are dispersed with the main residential areas being: Stanton Drew main village Upper Stanton Drew Tarnwell Highfields Stanton Wick There are also other smaller clusters of dwellings e.g. Bromley Villas and Bye Mills as well as individual farms and barns. Within the Parish there are two pubs, a church, village primary school and village hall. The Stones, which are of great archaeological and historical value, being the third largest collection of pre-historic standing stones in England, are situated in several locations in the northern sector of the Parish within the Conservation Area, with a newly discovered wooden henge within the boundaries of Quoit Farm on the northern edge of the Parish. -

St Chad's School Newsletter

St Chad’s School Newsletter Merry Christmas, everyone! are still raving about how much they en- and eve- Every term is a roller coaster of exciting joyed the trip. ryone things and term 2 has been no exception. As part of supporting safety in the wider had a We started with Years 2 and 3 having an world we have been holding pedestrian great author visit, meeting Tom Percival training and Level 1 cycle training time; (@TomPercivalsays) which was a great which as always has had a huge take up. some have even said they want to do skat- ing as a hobby! experience. Since our big push on writing Non-uniform day was a great success we have increasing numbers of pupils who in collecting for the Christmas tombola so This week has seen the productions, with want to be authors, so it was great for thank you to everyone who brought in an EYFS / Y1 Christmas production on them to chat with a very popular and suc- something. Monday, a Y2 Christmas production on cessful author to find out what it is like. Tuesday night, and a KS2 Carol Service in We have just held our first whole school On the 8th of November we held our first the Church on Wednesday night. I think house Spelling Bee Competition, everyone agrees that when you have pri- open morning. We had many parents, (following on from the success of our lan- carers and grandparents on site all having mary age children it really helps to remem- guages / culture quiz and sports events ber what Christmas is about, and these a great time. -

Justice & Peace Link Information Sheet on Events and Issues

Justice & Peace Link Information sheet on events and issues concerning justice & peace in and around Bristol and the Clifton Diocese March 2020 Ongoing until 4 March Fairtrade Fortnight. https://www.fairtrade.org.uk/en/get-involved/current-campaigns/fairtrade-fortnight until Tuesday, 31 March City Hall foyer, College Green, Bristol BS1 5TR “Mayors for Peace” art exhibition There are almost 8,000 members of “Mayors for Peace”, in 163 countries (including 80 other cities and towns in the UK). Since it’s formation in 1991, the stated aims of "Mayors for Peace" have been: “To contribute to the attainment of lasting world peace by arousing concern among citizens of the world for the total abolition of nuclear weapons through close solidarity among member cities as well as by striving to solve vital problems for the human race such as starvation and poverty, the plight of refugees, human rights abuses, and environmental degradation”. Bristol’s twin city, Hanover, launched this international art and peace project to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons signed by the nuclear-weapon states USA, the former Soviet Union, and the UK in 1968. The exhibition is currently touring member cities in Europe and North America in the hope that it will inspire local artistic and peace activities. Events Sunday, 1 March Pray and Fast for the Climate – 1st day of every month. The website includes a series of prayer points each month: https://prayandfastfortheclimate.org.uk/ Sunday, 1 March 10:45 am - 12:45 pm Mild West room level 3 (with lift), Hamilton House, 80 Stokes Croft, St Paul's, Bristol BS1 3QY How to be an effective Altruist a talk by Nick Lowry.