Download (14Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Additions to CASCAT from Carlisle Archives

Cumbria Archive Service CATALOGUE: new additions August 2021 Carlisle Archive Centre The list below comprises additions to CASCAT from Carlisle Archives from 1 January - 31 July 2021. Ref_No Title Description Date BRA British Records Association Nicholas Whitfield of Alston Moor, yeoman to Ranald Whitfield the son and heir of John Conveyance of messuage and Whitfield of Standerholm, Alston BRA/1/2/1 tenement at Clargill, Alston 7 Feb 1579 Moor, gent. Consideration £21 for Moor a messuage and tenement at Clargill currently in the holding of Thomas Archer Thomas Archer of Alston Moor, yeoman to Nicholas Whitfield of Clargill, Alston Moor, consideration £36 13s 4d for a 20 June BRA/1/2/2 Conveyance of a lease messuage and tenement at 1580 Clargill, rent 10s, which Thomas Archer lately had of the grant of Cuthbert Baynbrigg by a deed dated 22 May 1556 Ranold Whitfield son and heir of John Whitfield of Ranaldholme, Cumberland to William Moore of Heshewell, Northumberland, yeoman. Recites obligation Conveyance of messuage and between John Whitfield and one 16 June BRA/1/2/3 tenement at Clargill, customary William Whitfield of the City of 1587 rent 10s Durham, draper unto the said William Moore dated 13 Feb 1579 for his messuage and tenement, yearly rent 10s at Clargill late in the occupation of Nicholas Whitfield Thomas Moore of Clargill, Alston Moor, yeoman to Thomas Stevenson and John Stevenson of Corby Gates, yeoman. Recites Feb 1578 Nicholas Whitfield of Alston Conveyance of messuage and BRA/1/2/4 Moor, yeoman bargained and sold 1 Jun 1616 tenement at Clargill to Raynold Whitfield son of John Whitfield of Randelholme, gent. -

The Gretna Bombing – 7Th April 1941

Acknowledgements This booklet has been made possible by generous funding from the Heritage Lottery Fund, The Armed Forces Community Covenant and Dumfries and Galloway Council, who have all kindly given The Devil’s Porridge Museum the opportunity to share the fascinating story of heroic Border people. Special thanks are given to all those local people who participated in interviews which helped to gather invaluable personal insights and key local knowledge. A special mention is deserved for the trustees and volunteers of the Devil’s Porridge Museum, who had the vision and drive to pursue the Solway Military Coast Project to a successful conclusion. Many thanks also to the staff from local libraries and archives for their assistance and giving access to fascinating sources of information. Written and Researched by Sarah Harper Edited by Richard Brodie ©Eastriggs and Gretna Heritage Group (SCIO) 2018 1 th The Gretna Bombing – 7 April 1941 The township of Gretna was built during the First World War to house many of the workers who produced cordite at the ‘greatest munitions factory on Earth’ which straddled the Scottish-English border. You might be forgiven if you had thought that Gretna and its twin township of Eastriggs would be constructed on a functional basis with little attention to detail. This was the case in the early days when a huge timber town was built on a grid system for the labourers and tradesmen, but, so intent was the Government on retaining the vital workforce, that it brought in the best town planners and architects to provide pleasant accommodation. -

The Porridge Grand Tour of Scotland

PEERIE SHOP CAFÉ Shetland 24 ISLAND LARDER 23 Shetland THE PORRIDGE GRAND TOUR OF SCOTLAND KIRKWALL HOTEL SCOTLAND Orkney MACKAY’S HOTEL 13 Highlands GLENGOLLY B&B Highlands FOODSTORY CAFÉ Aberdeen LOCH NESS INN 14 12 Highlands SAND DOLLAR CAFÉ THREE CHIMNEYS Aberdeen Highlands BONOBO CAFÉ BALLINTAGGART Aberdeen FARM Perthshire 15 BRIDGEVIEW STATION THE WHITEHOUSE RESTAURANT RESTAURANT 11 Dundee & Angus Argyll & Bute 21 20 PORTERS BAR & 22 NINTH WAVE RESTAURANT RESTAURANT Dundee & Angus Argyll & Bute 19 4 MONACHYLE MHOR 18 10 9 TANNOCHBRAE TEA HOTEL ROOMS Stirlingshire 5 8 Fife 17 16 IT ALL STARTED HERE 2 Glasgow THE EDINBURGH 3 1 LARDER Edinburgh EUSEBI DELI 6 Glasgow CONTINI ON GEORGE STREET FIORLIN B&B Edinburgh Scottish Borders RESTAURANT MARK SELKIRK ARMS HOTEL 7 GREENAWAY Dumfries & Galloway Edinburgh THE ITINERARIES EDINBURGH TO PERTHSHIRE AND STIRLINGSHIRE DAY ONE When you arrive at Edinburgh via the Caledonian Sleeper, start the day o with a warming bowl of porridge with fresh apricots, bananas and toasted pecans and sunflower seeds at Contini on George Street 1 (available from 8am weekdays; 10am weekends). From there, why not take a walk up the Mound in Edinburgh to explore the Museum on the Mound and Edinburgh’s historic Royal Mile to work up your appetite for lunch. What’s on the menu? Porridge of course! Head to Blackfriar’s Street and the Edinburgh Larder 22 which has on oer slow cooked meat (beef or lamb) with seasonal vegetables and skirlie (an alternative to stuing which includes oatmeal). By now you’ll be itching for a bit of history so enjoy an underground history or ghost tour with Mercat Tours. -

Ww1gap Worksheet Answers

WW1Gap Worksheet answers HM Factory Gretna – Watch the film and look at the panels in The Devil’s Porridge Museum to find out the information to fill in the gaps. HM Factory Gretna was Britain’s largest munitions factory during WWI, stretching 9 miles along the Solway Coast from Dornock to Mossband. It was built in response to the shell crisis of 1915, when The Times newspaper reported The British Army was running dangerously short of artillery shells on The Western Front. This led to a change of government and the development of a national programme for munition production. A new government department was created to solve the munitions shortage with David Lloyd- George becoming the Minister of Munitions. Over 10 thousand labourers, mostly Irish navvies as well as 8,000 experts from the fields of chemistry, engineering and project management planned and built the factory in only 9 months. The townships of Gretna and Eastriggs were built to house the munition workers. These new settlements were seen as ideal communities, designed by the architects Raymond Unwin and Courtney Crickmer. The settlements had many amenities including church halls, shops, police barracks, a fire station, bakeries, a kitchen and dance halls. At its height, 30,000 people worked at HM Factory Gretna, 11,000 of whom were women. By June 1917, the factory produced1,100 tonnes of RDB cordite per week, more than all the other factories in Britain combined. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle visited the factory as a war correspondent and nicknamed the explosive mixture of nitro – cotton and nitro- glycerine the ‘Devil’s Porridge’. -

Housing Land Requirement Technical Paper Housing Land Requirement

Dumfries and Galloway Council Dumfries and Galloway Council LOCAL DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2 LOCAL DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2 ArchaeologicallyHousing Land SensitiveRequirement Areas (ASAs) TECHNICALTECHNICAL PAPERPAPER JANUARY 2018 JANUARY 2018 www.dumgal.gov.uk www.dumgal.gov.uk Local Development Plan 2 - Technical Paper Contents Introduction 3 Identifying Housing Need and Demand 3 Housing Supply Target (HST) 6 Setting the Housing Supply Target 35 Housing Land Requirement 37 Appendix A 40 Appendix B 43 2 Dumfries & Galloway Local Development Plan 2 – Proposed Plan: Housing Land Requirement Technical Paper Housing Land Requirement Introduction This Report explains the basis on which the housing land requirement contained in the Proposed Plan was determined. The performance of the adopted Local Development Plan (LDP) (Sept 2014) against the former housing land requirement is outlined within the LDP Monitoring Statement. The provision of land for housing and the timely release of that land to enable building of homes is a key component of the Plan. The broader objective of the Plan in relation to housing is the creation of places with a range and choice of well-located homes, ensuring that the right development comes forward within the right places. It is vital these considerations underpin the whole process of planning for housing even at the earliest stages of setting the housing land requirement. Identifying Housing Need and Demand An understanding and assessment of the need and demand for additional households within the area forms the basis for setting the housing supply target and the overall land requirement requiring to be allocated within the Local Development Plan 2 (LDP2). -

Annandale South Ward 10 Profile Annandale South Ward 10 Profile

Annandale South Ward 10 Profile Annandale South Ward 10 Profile Local Government Boundary Commission for Scotland Fifth Review of Electoral Arrangements Final Recommendations Dumfries & Galloway Council area Ward 10 (Annandale South) ward boundary 0 0 2.51M.52ilemillees Crown Copyright and database right 0 2 km 2016. All rights reserved. Ordnance ± Survey licence no. 100022179 Key statistics - Settlements Council and Partners Facilities Some details about the main towns and villages in Primary Schools the Annandale South Ward are given below Newington Primary School 376 The Royal Burgh of Annan is the principal town Elmvale Primary School 146 of Annandale and Eskdale and the third largest in Dumfries and Galloway. It has a population of 8389 Hecklegirth Primary School 238 with 4 primary schools and 1 secondary school. It is located on the B721 which is parallel with and St Columbas Primary School 58 linked to the nearby A74(M) and A75, and on the Curruthertown Primary School 26 Carlisle to Glasgow train route. The town contains a number of facilities including a busy high street Cummertrees Primary School 41 that is home to a variety of shops, museum, library, Brydekirk Primary School 33 leisure facilities, 5 churches, hotels and B&B’s. Eastriggs, Dornock and Creca has a population Secondary Schools of 1840 and is located on the B721 which is Annan Academy School 795 parallel with and linked to the nearby A74(M) and A75, and on the Carlisle to Glasgow train route, Customer Service Centres although no station currently exists. Eastriggs has Annan Customer Service Centre a small number of shops, post office, library, public Annan Registry Office house and church along with a primary school Eastriggs Customer Services Centre that feeds into Annan Academy. -

April 2021 Chairman’S Column

THE TIGER The ANZAC Commemorative Medalion, awarded in 1967 to surviving members of the Australian forces who served on the Gallipoli Peninsula or their next of kin THE NEWSLETTER OF THE LEICESTERSHIRE & RUTLAND BRANCH OF THE WESTERN FRONT ASSOCIATION ISSUE 113 – APRIL 2021 CHAIRMAN’S COLUMN Welcome again, Ladies and Gentlemen, to The Tiger. It would be improper for me to begin this month’s column without first acknowledging those readers who contacted me to offer their condolences on my recent bereavement. Your cards and messages were very much appreciated and I hope to be able to thank you all in person once circumstances permit. Another recent passing, reported via social media, was that of military writer and historian Lyn Macdonald, whose Great War books, based on eyewitness accounts of Great War veterans, may be familiar to many of our readers. Over the twenty years between 1978 and 1998, Lyn completed a series of seven volumes, the first of which, They Called It Passchendaele, was one of my earliest purchases when I began to seriously study the Great War. I suspect it will not surprise those of you who know me well to learn that all her other works also adorn my bookshelves! The recent announcement in early March of a proposed memorial to honour Indian Great War pilot Hardit Singh Malik (shown right) will doubtless be of interest to our “aviation buffs”. Malik was the first Indian ever to fly for the Royal Flying Corps, having previously served as an Ambulance driver with the French Red Cross. A graduate of Balliol College, Oxford, it was the intervention of his tutor that finally obtained Malik a cadetship in the R.F.C. -

Eastriggs, Dumfries and Galloway

(https://maps.google.com/maps?ll=56.358169,-6.286315&z=7&t=m&hl=en-GB&gl=UMSa&pm daapctlaie n©t=2a0p1iv83 G) eoBasis-DE/BKG (©2009), Google Eastriggs, Dumfries and Galloway Population 1,876 Eastriggs in Dumfries and Galloway is located between Annan and Gretna. It was planned as a settlement for the workers at the explosives factory in 1915, many of whom were migrants from Commonwealth countries, giving the settlement the name the Commonwealth Village. A munitions depot was established in WWII and the MOD used the site until 2010. This type of small town is extremely mixed in terms of demographics. There are particularly wide ranges of people, housing and activities. The number of older couples with no children is higher than average. There is a mix of professional and non- professional jobs, and part-time and self-employment are both important for a significant proportion of residents. Socioeconomic status is higher than in other types of town and there is a mix of professionals and nonprofessionals, those with higher and lower educational attainment. Eastriggs is a dependent to interdependent town. Its most similar towns are Shieldhill, Dunkeld and Birnam, Ochiltree, and Portknockie. To gain more insight into Eastriggs, compare it to any of the other towns included in USP. Inter-relationships Dependent Interdependent Independent NNuummbbeerr ooff jjjoobbss Number of jobs DDiiivveerrssiiittyy ooff jjjoobbss Diversity of jobs DDiiissttaannccee ttrraavveelllllleedd ttoo wwoorrkk Distance travelled to work NNuummbbeerr ooff ppuubbllliiicc -

Parish Profile ANNAN OLD PARISH CHURCH and DORNOCK CHURCH PARISH PROFILE 16/9/14

Annan Old Parish Church of Scotland linked with Dornock Parish Church of Scotland Annan Old Parish Church Dornock Parish Church Parish Profile ANNAN OLD PARISH CHURCH and DORNOCK CHURCH PARISH PROFILE 16/9/14 The Charge of Annan Old Parish Church of Scotland (also known as “Annan Old”, Scottish Charity No. SC010555) linked with Dornock Parish Church of Scotland (Charity No. SC004542) has two distinct parishes. The Linkage was formed in 2007 when the Minister at Dornock retired. The Dornock Parish also covers the nearby township of Eastriggs. The Charge had, until recently, the services of a Parish Assistant (shared with other local Church of Scotland churches). The post is currently vacant but it has been advertised and expected to be filled in the near future. There are, in addition, two retired Ministers and a Reader among the membership. ANNAN OLD PARISH CHURCH and HALL Both the church and hall are fitted with sound amplification and inductive loop The present church building, which is a Grade ‘A’ listed building, was erected in systems. 1789 and replaced the old Parish Church which stood on the site of the Town Hall. The church hall is owned by the congregation and was built in 1929. The It is a building typical of those commonly built at the time being oblong in shape premises comprise a large hall and with the chancel and pulpit central on the long south wall. Either side of the stage and is capable of seating 250 chancel are particularly fine commemorative stained glass windows which have people; a kitchen which has recently been renovated. -

Scottish Parliamentary Corporate Body

Meeting of the Parliament Wednesday 29 May 2019 Session 5 © Parliamentary copyright. Scottish Parliamentary Corporate Body Information on the Scottish Parliament’s copyright policy can be found on the website - www.parliament.scot or by contacting Public Information on 0131 348 5000 Wednesday 29 May 2019 CONTENTS Col. NEXT STEPS IN SCOTLAND’S FUTURE ................................................................................................................. 1 Statement—[Michael Russell]. The Cabinet Secretary for Government Business and Constitutional Relations (Michael Russell) ............. 1 PORTFOLIO QUESTION TIME ............................................................................................................................. 14 HEALTH AND SPORT ........................................................................................................................................ 14 Passive Smoking ........................................................................................................................................ 14 Health Services (Impact of Brexit) .............................................................................................................. 15 General Practitioner Recruitment (Rural Communities) ............................................................................. 16 Long-term Conditions (Art Therapy) ........................................................................................................... 17 NHS Grampian (Referral to Treatment Target) ......................................................................................... -

Book of Remembrance for Those Who Died in the Solway Within the Area of Annan

BOOK OF REMEMBRANCE FOR THOSE WHO DIED IN THE SOLWAY WITHIN THE AREA OF ANNAN compiled by Clive Bonner edited for website by Robert Mitchell 2019 Profits from the sale of this book to Annan United Reformed Church and Annandale Churches Together for their work in the community of Annan. © Clive Bonner 2009 ISBN 9781 899316540 1 Explanation This work of Remembrance has grown from a suggestion, made by a person who lost his own father to the Solway, that the Annan fishermen who died while fishing in the Solway should have a memorial in Annan. He felt it fitting that the memorial should be in that building he knew as the 'fisherman's church', that is the Annan United Reformed Church, which was from the 1890's to 2000 the Congregational Church. With the backing of the congregation of the Annan United Reformed Church and the members of Annandale Churches Together I undertook to do the research required to bring the memorial into being. A small group of people drawn from all the interested denominations within Annan was formed and at its only meeting was tasked with providing the names of fishermen who fitted the criterion to be included on the memorial. The criterion was to limit the memorial to those who sailed from Annan or were resident in Annan at the time of their loss. Using this information, I researched in the local and national newspapers to find the reports telling the known facts, obtained from people present at the time of the tragedies. I have transcribed the reports from either the original newspapers or microfiche and have only added detail to correct factual inaccuracies using information from death certificates and family when supplied. -

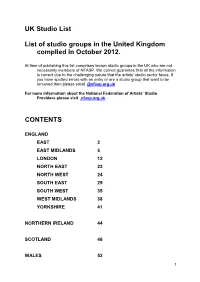

UK Studio List List of Studio Groups in the United Kingdom Complied In

UK Studio List List of studio groups in the United Kingdom complied in October 2012. At time of publishing this list comprises known studio groups in the UK who are not necessarily members of NFASP. We cannot guarantee that all the information is correct due to the challenging nature that the artists’ studio sector faces. If you have spotted errors with an entry or are a studio group that want to be removed then please email @nfasp.org.uk For more information about the National Federation of Artists’ Studio Providers please visit .nfasp.org.uk . CONTENTS ENGLAND EAST 2 EAST MIDLANDS 5 LONDON 12 NORTH EAST 22 NORTH WEST 24 SOUTH EAST 29 SOUTH WEST 35 WEST MIDLANDS 38 YORKSHIRE 41 NORTHERN IRELAND 44 SCOTLAND 46 WALES 52 1 ENGLAND EAST Alby Crafts & Gardens Cromer Road Erpingham Norwich NR11 7QE T:01263 761590 E:[email protected] W:www.albycrafts.co.uk Artshed Ware Ltd Westminll Farm Westmill Road Ware SG12 0ES T:01920 466 446 E:[email protected] W:www.artshedarts.co.uk/ Asylum Studios Building 118, Bentwaters Parks Rendlesham Woodbridge IP12 2TW T:01394 461557 E:[email protected] W:www.asylumstudios.co.uk/ Main Contact: Emma Withers Baas Farm Studios Baas Farm Studios, Broxbourne Herts EN10 7PX T:01992 443600 E:[email protected] Main Contact: V. G. Parsons 2 Butley Mills Studios Mill Lane Butley, Woodbridge Suffolk IP12 3PZ T:01394 450030 E:[email protected] Main Contact: Sian O'Keefe Courtyard Arts & Community Centre Port Vale Hertford SG14 3AA T:01992509596 E:[email protected] Main Contact: Melanie