Shakespeare and Race

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ANNUAL REVIEW 2015 -16 the RSC Acting Companies Are Generously Supported by the GATSBY CHARITABLE FOUNDATION and the KOVNER FOUNDATION

ANNUAL REVIEW 2015 -16 The RSC Acting Companies are generously supported by THE GATSBY CHARITABLE FOUNDATION and THE KOVNER FOUNDATION. Hugh Quarshie and Lucian Msamati in Othello. 2015/16 has been a blockbuster year for Shakespeare and for the RSC. 400th anniversaries do not happen often and we wanted to mark 2016 with an unforgettable programme to celebrate Shakespeare’s extraordinary legacy and bring his work to a whole new generation. Starting its life in Stratford-upon-Avon, Tom Morton-Smith about Oppenheimer, we staged A Midsummer Night’s a revival of Miller’s masterpiece Dream in every nation and region Death of a Salesman, marking his of the UK, with 84 amateurs playing centenary, and the reopening of Bottom and the Mechanicals and The Other Place, our new creative over 580 schoolchildren as Titania’s hub. Our wonderful production of fairy train. This magical production Matilda The Musical continued on has touched the lives of everyone its life-enhancing journey, playing involved and we are hugely grateful on three continents to an audience to our partner theatres, schools and of almost 2 million. the amateur companies for making this incredible journey possible. Our work showcased the fabulous range of diverse talent from across We worked in partnership with the the country, and we are proud of the BBC to bring ‘Shakespeare Live! From increasing diversity of our audiences. the RSC’ to a television audience of 1.6m and to cinema audiences in People sometimes ask if Shakespeare 15 countries. The glittering cast is still relevant. The response from performed in the Royal Shakespeare audiences everywhere has been a Theatre to an audience drawn from resounding ‘yes’. -

Shakespeare on Film, Video & Stage

William Shakespeare on Film, Video and Stage Titles in bold red font with an asterisk (*) represent the crème de la crème – first choice titles in each category. These are the titles you’ll probably want to explore first. Titles in bold black font are the second- tier – outstanding films that are the next level of artistry and craftsmanship. Once you have experienced the top tier, these are where you should go next. They may not represent the highest achievement in each genre, but they are definitely a cut above the rest. Finally, the titles which are in a regular black font constitute the rest of the films within the genre. I would be the first to admit that some of these may actually be worthy of being “ranked” more highly, but it is a ridiculously subjective matter. Bibliography Shakespeare on Silent Film Robert Hamilton Ball, Theatre Arts Books, 1968. (Reissued by Routledge, 2016.) Shakespeare and the Film Roger Manvell, Praeger, 1971. Shakespeare on Film Jack J. Jorgens, Indiana University Press, 1977. Shakespeare on Television: An Anthology of Essays and Reviews J.C. Bulman, H.R. Coursen, eds., UPNE, 1988. The BBC Shakespeare Plays: Making the Televised Canon Susan Willis, The University of North Carolina Press, 1991. Shakespeare on Screen: An International Filmography and Videography Kenneth S. Rothwell, Neil Schuman Pub., 1991. Still in Movement: Shakespeare on Screen Lorne M. Buchman, Oxford University Press, 1991. Shakespeare Observed: Studies in Performance on Stage and Screen Samuel Crowl, Ohio University Press, 1992. Shakespeare and the Moving Image: The Plays on Film and Television Anthony Davies & Stanley Wells, eds., Cambridge University Press, 1994. -

Universidade Federal De Santa Catarina Pós-Graduação Em Letras/Inglês E Literatura Correspondente

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE SANTA CATARINA PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM LETRAS/INGLÊS E LITERATURA CORRESPONDENTE SHAKESPEARE IN THE TUBE: THEATRICALIZING VIOLENCE IN BBC’S TITUS ANDRONICUS FILIPE DOS SANTOS AVILA Supervisor: Dr. José Roberto O’Shea Dissertação submetida ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Letras/Inglês e Literatura Correspondente da Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina em cumprimento parcial dos requisitos para obtenção do grau de MESTRE EM LETRAS FLORIANÓPOLIS MARÇO/2014 Agradecimentos CAPES pelo apoio financeiro, sem o qual este trabalho não teria se desenvolvido. Espero um dia retribuir, de alguma forma, o dinheiro investido no meu desenvolvimento intelectual e profissional. Meu orientador e, principalmente, herói intelectual, professor José Roberto O’Shea, por ter apoiado este projeto desde o primeiro momento e me guiado com sabedoria. My Shakespearean rivals (no sentido elisabetano), Fernando, Alex, Nicole, Andrea e Janaína. Meus colegas do mestrado, em especial Laísa e João Pedro. A companhia de vocês foi de grande valia nesses dois anos. Minha grande amiga Meggie. Sem sua ajuda eu dificilmente teria terminado a graduação (e mantido a sanidade!). Meus professores, especialmente Maria Lúcia Milleo, Daniel Serravalle, Anelise Corseuil e Fabiano Seixas. Fábio Lopes, meu outro herói intelectual. Suas leituras freudianas, chestertonianas e rodrigueanas dos acontecimentos cotidianos (e da novela Avenida Brasil, é claro) me influenciaram muito. Alguns russos que mantém um site altamente ilegal para download de livros. Sem esse recurso eu honestamente não me imaginaria terminando essa dissertação. Meus amigos. Vocês sabem quem são, pois ouviram falar da dissertação mais vezes do que gostariam ao longo desses dois anos. Obrigado pelo apoio e espero que tenham entendido a minha ausência. -

Julius Caesar

BAM 2013 Winter/Spring Season Brooklyn Academy of Music BAM, the Royal Shakespeare Company, Alan H. Fishman, and The Ohio State University present Chairman of the Board William I. Campbell, Vice Chairman of the Board Adam E. Max, Julius Vice Chairman of the Board Karen Brooks Hopkins, President Joseph V. Melillo, Caesar Executive Producer Royal Shakespeare Company By William Shakespeare BAM Harvey Theater Apr 10—13, 16—20 & 23—27 at 7:30pm Apr 13, 20 & 27 at 2pm; Apr 14, 21 & 28 at 3pm Approximate running time: two hours and 40 minutes, including one intermission Directed by Gregory Doran Designed by Michael Vale Lighting designed by Vince Herbert Music by Akintayo Akinbode Sound designed by Jonathan Ruddick BAM 2013 Winter/Spring Season sponsor: Movement by Diane Alison-Mitchell Fights by Kev McCurdy Associate director Gbolahan Obisesan BAM 2013 Theater Sponsor Julius Caesar was made possible by a generous gift from Frederick Iseman The first performance of this production took place on May 28, 2012 at the Royal Shakespeare Theatre, Leadership support provided by The Peter Jay Stratford-upon-Avon. Sharp Foundation, Betsy & Ed Cohen / Arete Foundation, and the Hutchins Family Foundation The Royal Shakespeare Company in America is Major support for theater at BAM: presented in collaboration with The Ohio State University. The Corinthian Foundation The Gladys Krieble Delmas Foundation Stephanie & Timothy Ingrassia Donald R. Mullen, Jr. The Fan Fox & Leslie R. Samuels Foundation, Inc. Post-Show Talk: Members of the Royal Shakespeare Company The Morris and Alma Schapiro Fund Friday, April 26. Free to same day ticket holders The SHS Foundation The Shubert Foundation, Inc. -

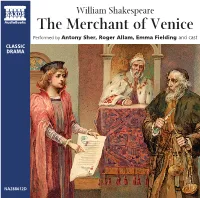

The Merchant of Venice Performed by Antony Sher, Roger Allam, Emma Fielding and Cast CLASSIC DRAMA

William Shakespeare The Merchant of Venice Performed by Antony Sher, Roger Allam, Emma Fielding and cast CLASSIC DRAMA NA288612D 1 Act 1 Scene 1: In sooth, I know not why I am so sad: 9:55 2 Act 1 Scene 2: By my troth, Nerissa, my little body is aweary… 7:20 3 Act 1 Scene 3: Three thousand ducats; well. 6:08 4 Signior Antonio, many a time and oft… 4:06 5 Act 2 Scene 1: Mislike me not for my complexion… 2:26 6 Act 2 Scene 2: Certainly my conscience… 4:21 7 Nay, indeed, if you had your eyes, you might fail of… 4:19 8 Father, in. I cannot get a service, no; 2:49 9 Act 2 Scene 3: Launcelot I am sorry thou wilt leave my father so: 1:15 10 Act 2 Scene 4: Nay, we will slink away in supper-time, 1:50 11 Act 2 Scene 5: Well Launcelot, thou shalt see, 3:16 12 Act 2 Scene 6: This is the pent-house under which Lorenzo… 1:32 13 Here, catch this casket; it is worth the pains. 1:49 14 Act 2 Scene 7: Go draw aside the curtains and discover… 5:04 15 O hell! what have we here? 1:23 16 Act 2 Scene 8: Why, man, I saw Bassanio under sail: 2:27 17 Act 2 Scene 9: Quick, quick, I pray thee; draw the curtain straight: 6:48 2 18 Act 3 Scene 1: Now, what news on the Rialto Salerino? 2:13 19 To bait fish withal: 5:17 20 Act 3 Scene 2: I pray you, tarry: pause a day or two… 4:39 21 Tell me where is fancy bred… 6:52 22 You see me, Lord Bassanio, where I stand… 9:56 23 Act 3 Scene 3: Gaoler, look to him: tell not of Mercy… 2:05 24 Act 3 Scene 4: Portia, although I speak it in your presence… 3:56 25 Act 3 Scene 5: Yes, truly; for, look you the sins of the father… 4:28 26 Act 4 Scene 1: What, is Antonio here? 4:42 27 What judgment shall I dread, doing. -

Abena Busia Oral History Content Summary

Abena Busia Oral History Content Summary Track 1 [duration: 1:35:50] [session one: 18 March 2016] [00:00] Abena Busia [AB] Born in Ghana. Describes spending most of childhood in exile, living in The Netherlands, Mexico. Move to Standlake, Windrush Valley, Oxfordshire, United Kingdom (UK) aged nine. Attendance of Standlake Church of England Primary School. Mentions Headmaster, Gordon Snelling for teaching that ‘everybody could be a poet’. Describes love of poetry, music, words in household. Mentions Witney Grammar School (now The Henry Box School), Headington School. Father, Kofi Abrefa Busia, Leader of the Opposition to Kwame Nkrumah during Ghana’s Independence. Mentions father university professor on sabbatical, Institute of Social Studies, The Hague. Anecdote about father as ‘praying person’. Describes father as staunch Methodist with purely Methodist education from primary school in Wenchi, Ghana, to Oxford University, UK. [05:08] Story about fleeing Ghana by ship aged six with mother and three siblings, borders closed in search of AB’s father. Remarks on mother’s bravery. Mentions Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, Ghana, Freetown, Sierra Leone, Clarks shoes, British Press, Elder Dempster Line. [11:14] Reflects on excitement of journey as a child. Mentions Rowntree’s Fruit Gums, learning to dance the Twist, films ‘Dr. No’, ‘She didn’t say No!’, ‘The Blue Angel’, ‘The Ten Commandments’, Elder Dempster Line SS Accra 3, SS Apam. [15:00] Recollections from early years in Ghana, growing up on University of Ghana campus. Mentions Fuchsia, Gladioli. Story about recurring memory of friend Susan Niculesku, Akwaaba doll. Describes having two exiles, first returning in 1966 after living in The Netherlands and Mexico. -

A Midsummer Night's Dream

CLASSIC DRAMA UNABRIDGED William Shakespeare A Midsummer Night’s Dream With Warren Mitchell Michael Maloney Sarah Woodward and full cast 1 Music and opening announcement 1:21 2 Act 1 Scene 1 6:20 3 Act 1 Scene 1: LYSANDER How now my love, why is your cheek so pale? 5:11 4 Act 1 Scene 1: HELENA How happy some o’er other some can be! 1:51 5 Musical interlude 0:49 6 Act 1 Scene 2 6:05 7 Musical interlude 1:06 8 Act 2 Scene 1 2:50 9 Act 2 Scene 1: OBERON Ill met by moonlight, proud Titania! 4:43 10 Act 2 Scene 1: OBERON Well, go thy way. Thou shalt not from this grove 2:20 11 Act 2 Scene 1: DEMETRIUS I love thee not, therefore pursue me not. 3:10 12 Act 2 Scene 1: OBERON I know a bank where the wild thyme blows 1:09 13 Musical interlude 1:43 14 Act 2 Scene 2 4:50 15 Act 2 Scene 2: PUCK Through the forest have I gone… 1:12 16 Act 2 Scene 2: HELENA Stay though thou kill me, sweet Demetrius! 3:32 2 17 Act 2 Scene 2: HERMIA Help me Lysander, Help me! 1:08 18 Closing music 1:49 19 Opening music 0:50 20 Act 3 Scene 1 7:29 21 Act 3 Scene 1: BOTTOM I see their knavery. This is to make an ass of me 5:16 22 Act 3 Scene 2 2:14 23 Act 3 Scene 2: DEMETRIUS O, why rebuke you him that loves you so? 2:38 24 Act 3 Scene 2: OBERON What hast thou done? Thou hast mistaken… 1:44 25 Act 3 Scene 2: LYSANDER Why should you think that I should woo… 3:52 26 Act 3 Scene 2: HELENA Lo, she is one of this confederacy 8:41 27 Act 3 Scene 2: OBERON This is thy negligence. -

Bfi Presents Shakespeare on Film with Ian Mckellen

BFI PRESENTS SHAKESPEARE ON FILM WITH IAN MCKELLEN BIGGEST EVER PROGRAMME OF SHAKESPEARE ON FILM IN THE UK AND ACROSS THE WORLD WITH THE BRITISH COUNCIL Ian McKellen live on stage to present re-mastered Richard III for UK wide simulcast, hosts London bus tours of Richard III’s iconic locations and opens Shanghai Film Festival with Shakespeare on Film International tour of 18 British films to 110 countries with British Council Play On! Shakespeare in Silent Cinema premieres at BFI Southbank with new live score by the Musicians of Shakespeare’s Globe New 4K restorations of Franco Zeffirelli’s Romeo and Juliet and Akira Kurosawa’s Ran Includes landmark films by Laurence Olivier, Orson Welles, Roman Polanski and Kenneth Branagh #ShakespeareLives / www.bfi.org.uk/shakespeare / www.shakespearelives.org Embargoed until 11:00 Monday 25 January 2016 As the world celebrates Shakespeare 400 years after his death, the BFI, the British Council and Ian McKellen today unveiled BFI Presents Shakespeare on Film. With no other writer impacting so greatly on cinema, this programme explores on an epic scale how filmmakers have adapted, been inspired by and interpreted Shakespeare’s work for the big screen. It incorporates screenings and events at BFI Southbank (April-May) and UK-wide, newly digitised content on BFI Player, new DVD/Blu-ray releases and film education activity. As part of Shakespeare Lives, the British Council and the GREAT Britain campaign’s major global programme for 2016, celebrating Shakespeare’s works and his influence on culture, education and society, the BFI has also curated an international touring programme of 18 key British Shakespeare films that will go to 110 countries – from Cuba to Iraq, Russia to the USA – the most extensive film programme ever undertaken. -

~Lagfblll COMPANIES INC

May 2000 Brooklyn Academy of Music 2000 Spring Season BAMcinematek Brooklyn Philharmonic 651 ARTS Saint Clair Cemin, L'lntuition de L'lnstant, 1995 BAM 2000 Spring Season is sponsored by PHiliP MORR I S ~lAGfBlll COMPANIES INC. ~81\L1 ,nri ng ~A~~On Brooklyn Academy of Music Bruce C. Ratner Chairman of the Board Karen Brooks Hopkins Joseph V. Melillo President Executive Producer presents The Royal Shakespeare Company Don Carlos Running time: by Friedrich Schiller approximately Translated by Robert David MacDonald 3 hours 15 minutes, BAM Harvey Lichtenstein Theater including one May 16-20, 2000, at 7:30pm intermission Director Gale Edwards Set design Peter J. Davison Costume design Sue Willmington Lighting design Mark McCullough Music Gary Yershon Fights Malcolm Ranson Sound Charles Horne Music direction Tony Stenson Assistant director Helen Raynor Company voice work Andrew Wade and Lyn Darnley Production manager Patrick Frazer Costume supervisor Jenny Alden Company stage manager Eric Lumsden Deputy stage manager Pip Horobin/Gabrielle Saunders Assistant stage manager Thea Jones American stage manager R. Michael Blanco The play Setting: Spain, the spring of 1568. Act One takes place at the Queen's court in Aranjuez; the remainder of the play is set in the Royal Palace , Madrid. Presented by arrangement with the Royal Shakespeare Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, England. RIC Leadership support is provided by The Peter Jay Sharp Foundation. ROYAL SHAKESPEARE BAM Theater is sponsored by Time Warner Inc. and Fleet Bank. COMPANY Additional support provided by The Shubert Foundation, Inc. Official Airline: British Airways. RSC major support provided by Pfizer Inc. This production was first produced with the assistance of a subsidy from the Arts Council of England. -

BBC ONE Spring/Summer 2002 5 Drama

Drama of Tony Blair, IT and gangsta rap can be strange DRAMA and comfortless, leaving these working-class heroes happy to try their luck at one more job. They cemented their friendships in Germany and Auf Wiedersehen, Pet Spain, and this new series takes the “cowboy” builders on an incredible journey from Middlesbrough to Arizona. “The timing seems absolutely right for the return of Auf Wiedersehen, Pet,” says Controller of Drama Commissioning, Jane Tranter. “The fact that all the original team have embraced it so enthusiastically demonstrates the power that the show still has to excite people. It’s moved on, in spirit and in time, and the maturity of the characters has brought a new edge and humour to the storytelling.” A BBC production for BBC ONE, Auf Wiedersehen, Pet is produced by Joy Spink and directed by Paul Seed. The executive producers are Laura Mackie and Franc Roddam. Being April Auf Wiedersehen, Pet, the hit drama of the Eighties, which followed the fortunes of an intrepid band of British brickies, returns to BBC ONE this spring. The production reunites the original cast of Jimmy Nail (Oz), Timothy Spall (Barry), Kevin Whately (Neville), Tim Healy (Dennis), Pat Roach (Bomber), Christopher Fairbank (Moxey) and newcomer Noel Clarke (Wyman), with original writers Dick Clement and Ian La Frenais and creator Franc Roddam. The last 15 years have been kinder to some of the lads than others. One drives a Bentley, another a taxi. Marriages have come and gone. But when Oz turns up with an irresistible offer, the “Magnificent Seven” find that the friendships they made on the road to Düsseldorf Three kids. -

Tiata Fahodzi Info Pack and Job Description.Pages

artistic director leadership programme spring 2017 “why keep going to the theatre if you seldom see yourself reflected there? Lyn Gardner, The Guardian 2014 !1 …gorgeous who we are theatre from a truly diverse company” Lenny Henry OBE tiata fahodzi (tee-ah-ta fa-hoon-zi) – a theatre company for Britain today and the Britain of tomorrow. tiata fahodzi was founded in 1997 by actor and director Femi Elufowoju Jnr. to tell stories about the African diaspora experience and to bring the richness and heritage of African theatre traditions to theatre-making here in the UK. Under his artistic directorship, the company sought to establish itself – project by project – through productions of contemporary texts by African writers, presented in London and sometimes regionally, offering a window into the West African experience – both back home and as immigrants to the UK. In 2010, actor Lucian Msamati became the company’s second Artistic Director. Earlier productions had told stories of emigration and diaspora (tickets and ties), and under Msamati the company’s work began to reflect on the relationship Britain and British Africans have with Africa. In late 2014, director Natalie Ibu took over as Artistic Director, and under her directorship we set ourselves to explore the mixed, multiple, multi- generational experience of what it is to be of African heritage in Britain today. In Natalie’s tenure, we continue to reflect the changing and developing diaspora with a particular interest in the dual and the in-between, in those who straddle worlds, cultures, languages, classes, heritages, races and struggles. It’s in this – the messy, the multiple and the complicated identity politics – that tiata fahodzi sits, acknowledging that our audiences are more complex and contrasting than ever. -

Hybridity in John Wyver's Bbc Shakespeare

TESIS DOCTORAL 2016-2017 HYBRIDITY IN JOHN WYVER’S BBC SHAKESPEARE FILMS: A STUDY OF GREGORY DORAN’S MACBETH (2001), HAMLET (2009) AND JULIUS CAESAR (2012) AND RUPERT GOOLD’S MACBETH (2010) Autor: Víctor Huertas Martín PROGRAMA DE DOCTORADO EN FILOLOGÍA. ESTUDIOS LINGÜÍSTICOS Y LITERARIOS: TEORÍA Y APLICACIONES DIRECTORA: MARTA CEREZO MORENO 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to thank John Wyver, whose contribution to the development of TV theatre has been the main inspiration for this doctoral dissertation. His generosity has been outstanding for having granted me two interviews where many clarifications and useful answers were offered to carry out this research. My heartiest acknowledgements belong to Dr. Marta Cerezo Moreno for her great supervising task, enthusiasm, optimism and energy; for her rigor at correction together with all the methodological and theoretical suggestions she has been making over these last three years. My acknowledgements should be extended to the teachers at the English Studies Department and other Humanities Departments at the UNED. Over a series of seminars, I have had the chance to meet some of them and their advice and contributions have been highly beneficial for my work. Also, I need to thank my partner Olga Escobar Feito for her unconditional support, for her kind words, her frequent smiles and her infinite patience over three years of coexistence with a frequently absent-minded PhD student buried in books and paper. It only remains to dedicate this work to my family, friends, colleagues and students. February 17, 2017 2 Table of Contents 0. INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................7 0.1. Research Statement ........................................................................................................... 8 0.2.