O:\BPJ 2001\BPJ 2001 Final\Fina

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

COST to COST Toshiba 2600 MORA 1St Floor, Farm Bhawan, 14-15 Nehru Place WD 2700 Seagate 2800 8GB-189/- 16GB-284/- Rate List Date: 05/09/2015

PEN DRIVE HDD 500 GB COST TO COST Toshiba 2600 MORA 1st Floor, Farm Bhawan, 14-15 Nehru Place WD 2700 Seagate 2800 8GB-189/- 16GB-284/- Rate List Date: 05/09/2015 A-DATA SSD (M-sata) 32GB 1790 40 AMD SEMPRON (2650) 2142 81 GIGABYTE H170- GAMING 3(11 10990 122 ASUS M5A78L-M/USB3 4090 41 AMD SEMPRON 145 1590 82 GIGABYTE H170- MD3H (1151) 8990 123 GIGABYTE AM1M-S2H 1990 CPU INTEL 42 AMD TRINITY A10 9190 83 GIGABYTE H81M-S (1150) 3090 124 GIGABYTE 78LMT-S2 2990 1 INTEL CELERON (G470)(1155) 2090 43 AMD TRINITY A4 2790 84 GIGABYTE Z170- D3H (1151) 12090 125 GIGABYTE 78LMT-USB 3 3990 2 INTEL DUAL CORE (G-2030)(115 3290 44 AMD TRINITY A6 3990 85 GIGABYTE Z170 GAMING 5 (11 17290 126 GIGABYTE 970A- DS3P 5290 3 INTEL DUAL CORE (G-3220)(115 3240 45 AMD TRINITY A8 5990 86 GIGABYTE Z170 GAMING 7 (11 20290 127 GIGABYTE A58M-S1 2990 4 INTEL DUAL CORE (G-3240)(115 3400 87 GIGABYTE Z170- MD3H (1151) 11290 128 GIGABYTE A68H-S-1 3390 5 INTEL E3 1220 V3 (SERVER) 13990 88 GIGABYTE ATOM KIT (J1800M-D 3790 129 GIGABYTE A88XM D3H 6290 6 INTEL E3 1230 V3 (SERVER) ASK BOARD INTEL CPU 89 GIGABYTE B85M D3H (1150) 5390 7 INTEL E3 1246 V3 (SERVER) ASK 46 ASROCK B85 (B95M-DGS)(1150 4190 90 GIGABYTE B85M DS3H-A (1150) 4990 8 INTEL I-3 (3220) (1155) 6590 47 ASROCK B85 M (1150) 5190 HARD DISK 91 GIGABYTE G1 SNIPER M5 (Z 87) 14490 9 INTEL I-3 (4130) (1150) 7090 48 ASROCK H61M-S1 PLUS (1155) 2890 130 1 TB WD BLACK CAVIOUR 5142 92 GIGABYTE GA H61M S (1155) 2990 10 INTEL I-3 (4150) (1150) 7090 49 ASROCK H61-VS4 2590 131 1 TB WD LAPTOP (2 YEAR) 3895 93 GIGABYTE GA- Z77M-D3H -

North American Company Profiles 8X8

North American Company Profiles 8x8 8X8 8x8, Inc. 2445 Mission College Boulevard Santa Clara, California 95054 Telephone: (408) 727-1885 Fax: (408) 980-0432 Web Site: www.8x8.com Email: [email protected] Fabless IC Supplier Regional Headquarters/Representative Locations Europe: 8x8, Inc. • Bucks, England U.K. Telephone: (44) (1628) 402800 • Fax: (44) (1628) 402829 Financial History ($M), Fiscal Year Ends March 31 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 Sales 36 31 34 20 29 19 50 Net Income 5 (1) (0.3) (6) (3) (14) 4 R&D Expenditures 7 7 7 8 8 11 12 Capital Expenditures — — — — 1 1 1 Employees 114 100 105 110 81 100 100 Ownership: Publicly held. NASDAQ: EGHT. Company Overview and Strategy 8x8, Inc. is a worldwide leader in the development, manufacture and deployment of an advanced Visual Information Architecture (VIA) encompassing A/V compression/decompression silicon, software, subsystems, and consumer appliances for video telephony, videoconferencing, and video multimedia applications. 8x8, Inc. was founded in 1987. The “8x8” refers to the company’s core technology, which is based upon Discrete Cosine Transform (DCT) image compression and decompression. In DCT, 8-pixel by 8-pixel blocks of image data form the fundamental processing unit. 2-1 8x8 North American Company Profiles Management Paul Voois Chairman and Chief Executive Officer Keith Barraclough President and Chief Operating Officer Bryan Martin Vice President, Engineering and Chief Technical Officer Sandra Abbott Vice President, Finance and Chief Financial Officer Chris McNiffe Vice President, Marketing and Sales Chris Peters Vice President, Sales Michael Noonen Vice President, Business Development Samuel Wang Vice President, Process Technology David Harper Vice President, European Operations Brett Byers Vice President, General Counsel and Investor Relations Products and Processes 8x8 has developed a Video Information Architecture (VIA) incorporating programmable integrated circuits (ICs) and compression/decompression algorithms (codecs) for audio/video communications. -

Final 2014 Return Shares for Electronics Manufacturers Washington State Electronic Products Recycling Program 4/24/2014

Final 2014 Return Shares for Electronics Manufacturers Washington State Electronic Products Recycling Program 4/24/2014 The E-Cycle Washington program conducted 42 sampling events in 2013 gathering data on over 13,600 TVs, monitors and computers. That data was used to determine Return Share by manufacturer, summarized below. Identified Proportional Total Manufacturer Name Weight (lbs) Brands Return Orphan* Return Share (%) Share (%) Share (%) 605484 92.80937069 Sony Electronics, Inc. 66834 11.04 0.86 11.89 Panasonic Corporation of North America 54226 8.96 0.69 9.65 Philips Electronics 47779 7.89 0.61 8.50 Toshiba America Information Systems, Inc. 43922 7.25 0.56 7.82 Dell Computer Corp. 43199 7.13 0.55 7.69 Thomson, Inc. USA 43078 7.11 0.55 7.67 Hewlett Packard 26370 4.36 0.34 4.69 JVC Americas Corp. 25979 4.29 0.33 4.62 Sharp Electronics Corporation 20274 3.35 0.26 3.61 Acer America Corp. 19327 3.19 0.25 3.44 LG Electronics USA, Inc. 18656 3.08 0.24 3.32 Mitsubishi Electric Visual Solutions America, Inc. 17906 2.96 0.23 3.19 Osram Sylvania 15226 2.51 0.19 2.71 Samsung Electronics Co. 14872 2.46 0.19 2.65 Apple 14537 2.40 0.19 2.59 Hitachi America, LTD. Digital Media Division 11235 1.86 0.14 2.00 ViewSonic Corp. World HQ 9934 1.64 0.13 1.77 Emerson Radio Corp. 7163 1.18 0.09 1.27 General Electric Co. 5691 0.94 0.07 1.01 NEC Display Solutions 4833 0.80 0.06 0.86 TMAX Digital, Inc. -

Driver Download Instructions

Download Instructions Microtek Scanmaker 6700 Usb Driver 8/13/2015 For Direct driver download: http://www.semantic.gs/microtek_scanmaker_6700_usb_driver_download#secure_download Important Notice: Microtek Scanmaker 6700 Usb often causes problems with other unrelated drivers, practically corrupting them and making the PC and internet connection slower. When updating Microtek Scanmaker 6700 Usb it is best to check these drivers and have them also updated. Examples for Microtek Scanmaker 6700 Usb corrupting other drivers are abundant. Here is a typical scenario: Most Common Driver Constellation Found: Scan performed on 8/15/2015, Computer: Toshiba Dynabook T451/59DB Outdated or Corrupted drivers:10/21 Updated Device/Driver Status Status Description By Scanner Motherboards Corrupted By Microtek Scanmaker Intel(R) N10/ICH7 Family PCI Express Root Port - 27D4 6700 Usb Mice And Touchpads Synaptics ThinkPad UltraNav Pointing Device Up To Date and Functioning Usb Devices Corrupted By Microtek Scanmaker Microsoft PM23300 6700 Usb Corrupted By Microtek Scanmaker usb-audio.de Burr-Brown USB Audio Codec 2706 (commercial 2.8.45) 6700 Usb Sound Cards And Media Devices NVIDIA NVIDIA GeForce GT 635M Up To Date and Functioning AVerMedia AVerMedia M791 PCIe Combo NTSC/ATSC Up To Date and Functioning Network Cards ASIX ThinkPad OneLink Dock USB GigaLAN Up To Date and Functioning Keyboards Microsoft HID Keyboard Up To Date and Functioning Hard Disk Controller NVIDIA NVIDIA nForce3 Parallel ATA Controller Outdated Others Intel Intel(r) AIM External Flat Panel -

Product Line Card

Product Line Card 3Com Corporation ATI Technologies Distribution CCT Technologies 3M Attachmate Corporation Century Software 4What, Inc. Autodesk, Inc. Certance 4XEM Avaya, Inc. Certance LLC Averatec America, Inc. Chanx Absolute Software Avocent Huntsville Corp. Check Point Software ACCPAC International, Inc. Axis Communications, Inc. Cherry Electrical Products Acer America Corporation Chicony Adaptec, Inc. Barracuda Networks Chief Manufacturing ADC Telecommunications Sales Battery Technology, Inc. Chili Systems Addmaster Bay Area Labels Cingular Interactive, L.P. Adesso Bay Press & Packing Cisco Systems, Inc. Adobe Systems, Inc. Belkin Corporation CMS Products, Inc. Adtran Bell & Howell CNET Technology, Inc. Advanced Digital Information BenQ America Corporation Codi Advanced Micro Devices, Inc. Best Case & Accessories Comdial AEB Technologies Best Software SB, Inc. Computer Associates Aegis Micro/Formosa– USA Bionic CCTV ComputerLand AI Coach Bionic Video Comtrol Corporation Alcatel Internetworking, Inc. Black Box Connect Tech All American Semi Block Financial Corel Corporation Allied Telesyn BorderWare Corporate Procurement Altec Lansing Technologies, Inc. Borland Software Corporation Corsair Althon Micro Boundless Technologies, Inc. Corsair Altigen Brady Worldwide Countertrade Products Alvarion, Inc. Brands, Inc. Craden AMCC Sales Corp. Brenthaven Creative Labs, Inc. AMD Bretford Manufacturing, Inc. CRU-Dataport American Portwell Technology Brooktrout Technology, Inc. CryptoCard American Power Conversion Brother International Corporation CTX Anova Microsystems Buffalo Technology/Melco Curtis Young Corporation Antec, Inc. Business Objects Americas AOpen America, Inc. BYTECC Dantz Development Corp. APC Data911 Arco Computer Products, LLC Cables To Go, Inc. Datago Ardence Cables Unlimited Dataram Areca. US Caldera Systems, Inc. Datawatch Corporation Arima Computer Cambridge Soundworks Decision Support Systems Artronix Canon USA Inc. Dedicated Micros Aspen Touch Solutions, Inc. Canton Electronics Corporation Dell Astra Data, Inc. -

Logos De Fabricantes De Semiconductores Semiconductor Manufacturers Logos

2013 Logos de fabricantes de semiconductores Semiconductor manufacturers logos EugenioNieto Vilardell Fidestec 15/03/2013 Logos de fabricantes de semiconductores 2013 2 8x8 Acer Acer Laboratories Acrian Actel ADDtek ADMtek Advanced Analogic Technology Advanced Communication Devices(ACD) Advanced Hardware Architectures Advanced Linear Devices Advanced Micro Devices(AMD) Advanced Micro Systems Advanced Monolithic Systems Advanced Power Technology Aeroflex Agere (formerly Lucent) Agilent Technologies Aimtron AITech International aJile Systems AKM Semiconductor Alchemy Semiconductor Alesis Semiconductor Allayer Communications(Now Broadcom) Allegro Microsystems Alliance Semiconductor Alogics Alpha & Omega Semiconductor Alpha Industries Alpha Microelectronics Alpha Semiconductor(Now Sipex) Altera Altima Communications AME Inc American Microsystems American Power Devices Logos de fabricantes de semiconductores 2013 3 AMIC Technology Anachip ANADIGICS Anadigm Analog Devices Analog Express Corp. Analog Integrations Corporation Analog Systems Anchor Chips Andigilog Anpec Ansaldo (Now Poseico) Apex Microtechnology API NetWorks Arizona Microtek ARK Logic Array Microsystems Astec Semiconductor AT&T ATAN Technology ATecoM ATI Technologies Atmel Auctor AudioCodes AUK Semiconductor Corp. Aura Vision Aureal Aurora Systems Austin Semiconductor Austria Mikro Systeme International Avance Logic Avantek Averlogic Avic Electronics Corp. AXElite Technology Co., Ltd BCD Semiconductor Manufacturing Limited Bel Fuse Logos de fabricantes de semiconductores 2013 -

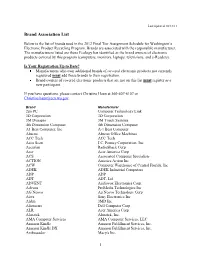

Brand Association List Is Your Registration up to Date?

Last updated: 7/30/19 Brand Association List Below is the list of brands used in the 2020 Tier Assignment Schedule for Washington’s Electronic Product Recycling Program. Brands are associated with the responsible manufacturer. The manufacturers listed are those Ecology has identified as the brand owners of electronic products covered by this program (computers, monitors, laptops, televisions, portable DVD players, tablets, and e-Readers). Is Your Registration Up to Date? • Manufacturers who own additional brands of covered electronic products not currently registered must add those brands to their registration. • Brand owners of covered electronic products that are not on this list must register as a new participant. • Access your registration by going to our webpage for manufacturers and clicking “Submit my annual registration.” If you have questions, please contact Jade Monroe at 360-407-7157 or [email protected]. Brand Manufacturer 2go PC Computer Technology Link 3D Corporation 3D Corporation 3M Dynapro 3M Touch Systems 4th Dimension Computer 4th Dimension Computer 888 (Chinese Characters) Fry's Electronics, Inc. Abacus Abacus Office Machines ABS ABS Computer Technologies Inc ABS Newegg ACC Tech ACC Tech ACC Tech Angel Computer Systems Inc Access HD GXi International Accu Scan J.C. Penney Corporation, Inc. Accurian General Wireless Operations Inc dba RadioShack Accuvision QubicaAMF Acer Acer America Corp ACI Micro ACI Micro ACW Computer Warehouse of Central Florida, Inc ADEK ADEK Industrial Computers Ademco Honeywell ACS Division ADP ADP ADT ADT LLC dba ADT Security Services ADVENT VOXX International Corp. Affinity Kith Consumer Product Inc. AFUNTA Afunta LLC Last updated: 7/30/19 AG Neovo AG Neovo Technology Corp Agasio Amcrest Technologies LLC AGPTEK Mambate USA, Inc. -

2009 Preliminary Tier Assignment, Alphabetic by Manufacturer

Last updated 10/13/11 Brand Association List Below is the list of brands used in the 2012 Final Tier Assignment Schedule for Washington’s Electronic Product Recycling Program. Brands are associated with the responsible manufacturer. The manufacturers listed are those Ecology has identified as the brand owners of electronic products covered by this program (computers, monitors, laptops, televisions, and e-Readers). Is Your Registration Up to Date? Manufacturers who own additional brands of covered electronic products not currently registered must add those brands to their registration. Brand owners of covered electronic products that are not on this list must register as a new participant. If you have questions, please contact Christine Haun at 360-407-6107 or [email protected]. Brand Manufacturer 2go PC Computer Technology Link 3D Corporation 3D Corporation 3M Dynapro 3M Touch Systems 4th Dimension Computer 4th Dimension Computer A1 Best Computer, Inc A-1 Best Computer Abacus Abacus Office Machines ACC Tech ACC Tech Accu Scan J.C. Penney Corporation, Inc. Accurian RadioShack Corp Acer Acer America Corp ACS Associated Computer Specialists ACTION America Action Inc ACW Computer Warehouse of Central Florida, Inc ADEK ADEK Industrial Computers ADP ADP ADT ADT, Ltd ADVENT Audiovox Electronics Corp. Advueu ProMedia Technologies Inc AG Neovo Ag Neovo Technology Corp Aiwa Sony Electronics Inc Alden 3MD Inc. Alienware Dell Computer Corp ALR Acer America Corp Aluratek Aluratek, Inc. AMA Computer Services AMA Computer Services, LLC Amazon Kindle Amazon Fulfillment Services, Inc. Amazon Kindle DX Amazon Fulfillment Services, Inc. Ambassador Macy's Inc. 1 AMBRA International Business Machines Corp. -

Silicon Valley's New Immigrant Entrepreneurs

Silicon Valley’s New Immigrant Entrepreneurs ••• AnnaLee Saxenian 1999 PUBLIC POLICY INSTITUTE OF CALIFORNIA Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Saxenian, AnnaLee. Silicon Valley’s new immigrant entrepreneurs / AnnaLee Saxenian. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN: 1-58213-009-4 1. Asian American businesspeople—California—Santa Clara County. 2. Asian American scientists—California—Santa Clara. 3. Immigrants—California—Santa Clara County. I. Title. HD2344.5.U62S367 1999 331.6'235'079473—dc21 99-28139 CIP Copyright © 1999 by Public Policy Institute of California All rights reserved San Francisco, CA Short sections of text, not to exceed three paragraphs, may be quoted without written permission provided that full attribution is given to the source and the above copyright notice is included. Research publications reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the staff, officers, or Board of Directors of the Public Policy Institute of California. Foreword In the 1940s, the author Carey McWilliams coined a phrase to characterize California’s penchant for innovation and experimentation. He called it “the edge of novelty” and remarked that “Californians have become so used to the idea of experimentation—they have had to experiment so often—that they are psychologically prepared to try anything.” Waves of migrants and immigrants over the past 150 years of California history have been attracted to our “edge of novelty,” and they have consistently found California a place that fosters creativity and the entrepreneurial spirit. In this report, AnnaLee Saxenian documents one of the latest, and most dramatic, examples of California as a location that attracts immigrant entrepreneurs. -

Manufacturers Page 1 of 20

Manufacturers Manufacturers Manufacturer Name Date Added 3COM 3M 7-Zip 11/13/2013 Aaron Bishell 11/13/2013 AASHTO ABISource Access Data 10/25/2013 Acer ACL ACRO Software Inc Acronis ACS Gov Systems ACT Actiontec Active PDF ActiveState ActivIdentity 11/13/2013 Adaptec Adaptive ADC Kentrox ADI ADIC ADIX Adkins Resource Adobe ADT ADTRAN Advanced Dynamics Advanced Toolware Advantage Software AE Tools Agfa AGILENT AHCCCS 11/13/2013 Ahead Ai Squared, Inc. 11/13/2013 Aladdin Alera Technologies Alex Feinman 11/13/2013 Alex Sirota 11/13/2013 ALIEN Allegro Allison Transmission Alltel AlphaSmart Altec Lansing Altiris Altova Altronix AMC AMD Amdahl Page 1 of 20 Manufacturers Manufacturer Name Date Added America Online American Business American Cybernetics American Dynamics 11/13/2013 AMX (Formerly ProCon) Analog Devices 11/13/2013 Analytical Software Andover Andrew Antony Lewis 11/13/2013 ANYDoc AOL AOpen AP Technology Apache APC Apex Apple Applian Technologies Appligent Aptana ArcSoft, Inc. 11/13/2013 Artifex Software Inc 11/13/2013 ASAP 11/13/2013 Ascential Software ASG Ask.com 11/13/2013 Aspose AST Astaro AT&T ATI Technologies 11/13/2013 Atlassian Attachmate Audacity AuthenTec 11/13/2013 Auto Enginuity Autodesk AutoIt Team 11/13/2013 Avantstar Avaya Aventail Avenza Systems Inc Averatec Avery Dennison AVG Technologies Avistar Avocent Axosoft Bamboo Banner Blue Barracuda BarScan Bay Networks Page 2 of 20 Manufacturers Manufacturer Name Date Added Bay Systems BEA System BEE-Line Software Belarc Belkin Bell & Howell Bendata BENQ BEST Best Software -

Qualified Vendors List – Devices 1. Power Supplies

Qualified Vendors List – Devices 1. Power Supplies Model AcBel R88 PC7063 700W Aero Cool STRIKE-X 600W EA-500D 500W EA-650 EarthWatts Green 650W Antec EDG750 750W HCP-1000 1000W TP-750C 750W AYWUN A1-550-ELITE 550W BQ L8-500W Be quiet BQT L7-530W BitFenix FURY 650G 650W BUBALUS PG800AAA 700W RS-550-ACAA-B1 550W RS-750-AMAA-G1 750W CoolerMaster RS-850-AFBA-G1 850W RS-A00-SPPA-D3 1000W RS-C00-AFBA-G1 1200W AX1500i 75-001971 1500W CMPSU-850TXM 850W CS850M 75-010929 850W CX850M 75-011012 850W Corsair CX750M 750W RM750-RPS0019 750W RPS0002 (HX750i) 750W RPS0007 (RM650i) 650W RPS0014 (RM550x) 550W D.HIGH DHP-200KGH-80P 1000W ERV1200EWT-G 1200W EnerMAX ERX730AWT 730W ETL450AWT-M 450W EVGA 220-P2-1200-X1 1200W FSP PT-650M 650W Huntkey WD600 600W JPower SP-1000PS-1M 1000W OCZ OCZ-FTY750W 750W Power Man IP-S450HQ7-0 450W HIVE-850S 850W Rosewill PHOTON-1200 1200W RBR1000-M 1000W S12 II SS-330GB 330W SS-1200XP3 Active PFC F3 1200W Seasonic SS-400FL 400W SSR-450RM Active PFC F3 450W Seventeam ST-550P-AD 550W SST-60F-P 600W Silverstone SST-ST85F-GS 850W Copyright 2015 ASUSTeK Computer Inc. PAGE 1 Z170-PREMIUM Model Super Flower SF-1000F14MP 1000W Toughpower TPX775 775W Thermaltake TPD-1200M 1200W TPG-0850D 850W 2. Hard Drives 2.1. HDD Devices Type Model H31K40003254SA H3IKNAS600012872SA Hitachi HDS723030ALA640 HDS724040ALE640 Samsung HD103SM ST1000DM003 ST1000LM014-3Y/P ST1000NM0011 ST1000DX001 ST1000NX0303 ST2000NM0033 Seagate ST2000NX0243 ST3000DM001 ST4000DM000 ST500DM002 ST500LM000-3Y/P ST6000NM0024 SATA 6G ST750LX003 Toshiba HDS721010DLE630 WD1002FAEX WD1003FZEX WD10EZEX WD10J31X WD10PURX WD20EFRX WD20PURX WD25EZRX WD WD30EFRX WD30EZRX WD4001FAEX WD5000AAKX WD5000AZLX WD5000HHTZ WD60EFRX WD60EZRX Hitachi HDS721050CLA362 Simmtrnics HDP725050GLA360 ST3750528AS Seagate ST95005620AS SATA 3G MK5061SYN Toshiba MK5061GSYN WD30EZRS WD WD5000BPKT Copyright 2015 ASUSTeK Computer Inc. -

Last Updated 10/02/12 Brand Association List Below Is the List Of

Last updated 10/02/12 Brand Association List Below is the list of brands used in the 2013 Final Tier Assignment Schedule for Washington’s Electronic Product Recycling Program. Brands are associated with the responsible manufacturer. The manufacturers listed are those Ecology has identified as the brand owners of electronic products covered by this program (computers, monitors, laptops, televisions, tablets, and e-Readers). Is Your Registration Up to Date? • Manufacturers who own additional brands of covered electronic products not currently registered must add those brands to their registration. • Brand owners of covered electronic products that are not on this list must register as a new participant. If you have questions, please contact Christine Haun at 360-407-6107 or [email protected]. Brand Manufacturer 2go PC Computer Technology Link 3D Corporation 3D Corporation 3M Dynapro 3M Touch Systems 4th Dimension Computer 4th Dimension Computer A1 Best Computer, Inc computer-fix Abacus Abacus Office Machines ACC Tech ACC Tech Access HD GXi International Accu Scan J.C. Penney Corporation, Inc. Accurian RadioShack Corp Acer Acer America Corp ACI Micro ACI Micro ACS Associated Computer Specialists ACTION America Action Inc ACW Computer Warehouse of Central Florida, Inc ADEK ADEK Industrial Computers ADP ADP ADT ADT, Ltd ADVENT Audiovox Electronics Corp. Advueu ProMedia Technologies Inc Affinity Kith Consumer Product Inc. Afunta Afunta, LLC AG Neovo AG Neovo Technology Corp Agasio Amcrest Technologies LLC AGPTEK Mambate USA, Inc. Aiwa Sony Electronics Inc Alden 3MD Inc. Alienware Dell Computer Corp Allegra Electronics Calypso Electronics ALR Acer America Corp Last updated 10/02/12 Aluratek Aluratek, Inc.