Taxonomy of the Extra-Solar Planet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lurking in the Shadows: Wide-Separation Gas Giants As Tracers of Planet Formation

Lurking in the Shadows: Wide-Separation Gas Giants as Tracers of Planet Formation Thesis by Marta Levesque Bryan In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy CALIFORNIA INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY Pasadena, California 2018 Defended May 1, 2018 ii © 2018 Marta Levesque Bryan ORCID: [0000-0002-6076-5967] All rights reserved iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost I would like to thank Heather Knutson, who I had the great privilege of working with as my thesis advisor. Her encouragement, guidance, and perspective helped me navigate many a challenging problem, and my conversations with her were a consistent source of positivity and learning throughout my time at Caltech. I leave graduate school a better scientist and person for having her as a role model. Heather fostered a wonderfully positive and supportive environment for her students, giving us the space to explore and grow - I could not have asked for a better advisor or research experience. I would also like to thank Konstantin Batygin for enthusiastic and illuminating discussions that always left me more excited to explore the result at hand. Thank you as well to Dimitri Mawet for providing both expertise and contagious optimism for some of my latest direct imaging endeavors. Thank you to the rest of my thesis committee, namely Geoff Blake, Evan Kirby, and Chuck Steidel for their support, helpful conversations, and insightful questions. I am grateful to have had the opportunity to collaborate with Brendan Bowler. His talk at Caltech my second year of graduate school introduced me to an unexpected population of massive wide-separation planetary-mass companions, and lead to a long-running collaboration from which several of my thesis projects were born. -

Where Are the Distant Worlds? Star Maps

W here Are the Distant Worlds? Star Maps Abo ut the Activity Whe re are the distant worlds in the night sky? Use a star map to find constellations and to identify stars with extrasolar planets. (Northern Hemisphere only, naked eye) Topics Covered • How to find Constellations • Where we have found planets around other stars Participants Adults, teens, families with children 8 years and up If a school/youth group, 10 years and older 1 to 4 participants per map Materials Needed Location and Timing • Current month's Star Map for the Use this activity at a star party on a public (included) dark, clear night. Timing depends only • At least one set Planetary on how long you want to observe. Postcards with Key (included) • A small (red) flashlight • (Optional) Print list of Visible Stars with Planets (included) Included in This Packet Page Detailed Activity Description 2 Helpful Hints 4 Background Information 5 Planetary Postcards 7 Key Planetary Postcards 9 Star Maps 20 Visible Stars With Planets 33 © 2008 Astronomical Society of the Pacific www.astrosociety.org Copies for educational purposes are permitted. Additional astronomy activities can be found here: http://nightsky.jpl.nasa.gov Detailed Activity Description Leader’s Role Participants’ Roles (Anticipated) Introduction: To Ask: Who has heard that scientists have found planets around stars other than our own Sun? How many of these stars might you think have been found? Anyone ever see a star that has planets around it? (our own Sun, some may know of other stars) We can’t see the planets around other stars, but we can see the star. -

Curriculum Vitae - 24 March 2020

Dr. Eric E. Mamajek Curriculum Vitae - 24 March 2020 Jet Propulsion Laboratory Phone: (818) 354-2153 4800 Oak Grove Drive FAX: (818) 393-4950 MS 321-162 [email protected] Pasadena, CA 91109-8099 https://science.jpl.nasa.gov/people/Mamajek/ Positions 2020- Discipline Program Manager - Exoplanets, Astro. & Physics Directorate, JPL/Caltech 2016- Deputy Program Chief Scientist, NASA Exoplanet Exploration Program, JPL/Caltech 2017- Professor of Physics & Astronomy (Research), University of Rochester 2016-2017 Visiting Professor, Physics & Astronomy, University of Rochester 2016 Professor, Physics & Astronomy, University of Rochester 2013-2016 Associate Professor, Physics & Astronomy, University of Rochester 2011-2012 Associate Astronomer, NOAO, Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory 2008-2013 Assistant Professor, Physics & Astronomy, University of Rochester (on leave 2011-2012) 2004-2008 Clay Postdoctoral Fellow, Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics 2000-2004 Graduate Research Assistant, University of Arizona, Astronomy 1999-2000 Graduate Teaching Assistant, University of Arizona, Astronomy 1998-1999 J. William Fulbright Fellow, Australia, ADFA/UNSW School of Physics Languages English (native), Spanish (advanced) Education 2004 Ph.D. The University of Arizona, Astronomy 2001 M.S. The University of Arizona, Astronomy 2000 M.Sc. The University of New South Wales, ADFA, Physics 1998 B.S. The Pennsylvania State University, Astronomy & Astrophysics, Physics 1993 H.S. Bethel Park High School Research Interests Formation and Evolution -

100 Closest Stars Designation R.A

100 closest stars Designation R.A. Dec. Mag. Common Name 1 Gliese+Jahreis 551 14h30m –62°40’ 11.09 Proxima Centauri Gliese+Jahreis 559 14h40m –60°50’ 0.01, 1.34 Alpha Centauri A,B 2 Gliese+Jahreis 699 17h58m 4°42’ 9.53 Barnard’s Star 3 Gliese+Jahreis 406 10h56m 7°01’ 13.44 Wolf 359 4 Gliese+Jahreis 411 11h03m 35°58’ 7.47 Lalande 21185 5 Gliese+Jahreis 244 6h45m –16°49’ -1.43, 8.44 Sirius A,B 6 Gliese+Jahreis 65 1h39m –17°57’ 12.54, 12.99 BL Ceti, UV Ceti 7 Gliese+Jahreis 729 18h50m –23°50’ 10.43 Ross 154 8 Gliese+Jahreis 905 23h45m 44°11’ 12.29 Ross 248 9 Gliese+Jahreis 144 3h33m –9°28’ 3.73 Epsilon Eridani 10 Gliese+Jahreis 887 23h06m –35°51’ 7.34 Lacaille 9352 11 Gliese+Jahreis 447 11h48m 0°48’ 11.13 Ross 128 12 Gliese+Jahreis 866 22h39m –15°18’ 13.33, 13.27, 14.03 EZ Aquarii A,B,C 13 Gliese+Jahreis 280 7h39m 5°14’ 10.7 Procyon A,B 14 Gliese+Jahreis 820 21h07m 38°45’ 5.21, 6.03 61 Cygni A,B 15 Gliese+Jahreis 725 18h43m 59°38’ 8.90, 9.69 16 Gliese+Jahreis 15 0h18m 44°01’ 8.08, 11.06 GX Andromedae, GQ Andromedae 17 Gliese+Jahreis 845 22h03m –56°47’ 4.69 Epsilon Indi A,B,C 18 Gliese+Jahreis 1111 8h30m 26°47’ 14.78 DX Cancri 19 Gliese+Jahreis 71 1h44m –15°56’ 3.49 Tau Ceti 20 Gliese+Jahreis 1061 3h36m –44°31’ 13.09 21 Gliese+Jahreis 54.1 1h13m –17°00’ 12.02 YZ Ceti 22 Gliese+Jahreis 273 7h27m 5°14’ 9.86 Luyten’s Star 23 SO 0253+1652 2h53m 16°53’ 15.14 24 SCR 1845-6357 18h45m –63°58’ 17.40J 25 Gliese+Jahreis 191 5h12m –45°01’ 8.84 Kapteyn’s Star 26 Gliese+Jahreis 825 21h17m –38°52’ 6.67 AX Microscopii 27 Gliese+Jahreis 860 22h28m 57°42’ 9.79, -

Naming the Extrasolar Planets

Naming the extrasolar planets W. Lyra Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, K¨onigstuhl 17, 69177, Heidelberg, Germany [email protected] Abstract and OGLE-TR-182 b, which does not help educators convey the message that these planets are quite similar to Jupiter. Extrasolar planets are not named and are referred to only In stark contrast, the sentence“planet Apollo is a gas giant by their assigned scientific designation. The reason given like Jupiter” is heavily - yet invisibly - coated with Coper- by the IAU to not name the planets is that it is consid- nicanism. ered impractical as planets are expected to be common. I One reason given by the IAU for not considering naming advance some reasons as to why this logic is flawed, and sug- the extrasolar planets is that it is a task deemed impractical. gest names for the 403 extrasolar planet candidates known One source is quoted as having said “if planets are found to as of Oct 2009. The names follow a scheme of association occur very frequently in the Universe, a system of individual with the constellation that the host star pertains to, and names for planets might well rapidly be found equally im- therefore are mostly drawn from Roman-Greek mythology. practicable as it is for stars, as planet discoveries progress.” Other mythologies may also be used given that a suitable 1. This leads to a second argument. It is indeed impractical association is established. to name all stars. But some stars are named nonetheless. In fact, all other classes of astronomical bodies are named. -

Exodata: a Python Package to Handle Large Exoplanet Catalogue Data

ExoData: A Python package to handle large exoplanet catalogue data Ryan Varley Department of Physics & Astronomy, University College London 132 Hampstead Road, London, NW1 2PS, United Kingdom [email protected] Abstract Exoplanet science often involves using the system parameters of real exoplanets for tasks such as simulations, fitting routines, and target selection for proposals. Several exoplanet catalogues are already well established but often lack a version history and code friendly interfaces. Software that bridges the barrier between the catalogues and code enables users to improve the specific repeatability of results by facilitating the retrieval of exact system parameters used in an arti- cles results along with unifying the equations and software used. As exoplanet science moves towards large data, gone are the days where researchers can recall the current population from memory. An interface able to query the population now becomes invaluable for target selection and population analysis. ExoData is a Python interface and exploratory analysis tool for the Open Exoplanet Cata- logue. It allows the loading of exoplanet systems into Python as objects (Planet, Star, Binary etc) from which common orbital and system equations can be calculated and measured parame- ters retrieved. This allows researchers to use tested code of the common equations they require (with units) and provides a large science input catalogue of planets for easy plotting and use in research. Advanced querying of targets are possible using the database and Python programming language. ExoData is also able to parse spectral types and fill in missing parameters according to programmable specifications and equations. Examples of use cases are integration of equations into data reduction pipelines, selecting planets for observing proposals and as an input catalogue to large scale simulation and analysis of planets. -

Edwin S. Kite [email protected] Sseh.Uchicago.Edu Citizenship: US, UK Appointments: University of Chicago: January 2015 – Assistant Professor

Edwin S. Kite [email protected] sseh.uchicago.edu Citizenship: US, UK Appointments: University of Chicago: January 2015 { Assistant Professor. Princeton University: January 2014 { December 2014 Harry Hess Fellow. Joint postdoc, Astrophysics and Geoscience departments. California Institute of Technology: January 2012 { January 2014 O.K. Earl Fellow (Divisional fellowship), Division of Geological & Planetary Sciences Education: M.Sci & B.A. Cambridge University: June 2007 M.Sci Natural Sciences Tripos (Geological Sciences). First Class. B.A. Natural Sciences Tripos (Geological Sciences). First Class. Ph.D. University of California, Berkeley: December 2011 Berkeley Fellowship. Awards and Distinctions: National Academy of Sciences - Committee on Astrobiology and Planetary Science 2017- American Geophysical Union - Greeley Early Career Award in Planetary Science 2016. Caltech O.K. Earl Postdoctoral Fellowship 2012-2013 (Division-wide fellowship). AAAS Newcomb Cleveland Prize 2009 (most outstanding Science paper; shared). Papers 58. Kite, E.S. & Barnett, M.N., 2020, \Exoplanet Secondary Atmosphere Loss and Revival," Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(31), 18264- = mentee 18271 (2020) 57. Kite, E.S., Steele, L.J., Mischna, M.A., & Richardson, M.I., \Strong Water Ice Cloud Greenhouse Warming In a 3D Model of Early Mars," (in revision) 56. Warren, A.O., Holo, S., Kite, E.S., & Wilson, S.A. \Overspilling Small Craters On A Dry Mars: Insights From Breach Erosion Modeling," Earth & Plan- etary Science Letters (in review) 55. Fan, B., Shaw, T.A., Tan, Z., & Kite, E.S., \Regime Transition of Tropi- cal Precipitation From Moist Climates to Desert-Planet Climates." Geophysical Research Letters (to be submitted) 54. Kite, E.S., Fegley, B., Schaefer, L., & Ford, E.B., \Atmosphere Origins for Exoplanet Sub-Neptunes," Astrophysical Journal, 891:111 (16 pp) (2020) 53. -

© in This Web Service Cambridge University

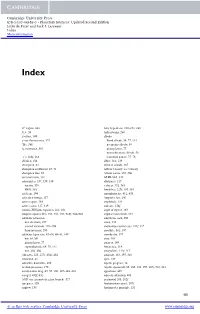

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-09161-0 - Planetary Sciences: Updated Second Edition Imke de Pater and Jack J. Lissauer Index More information Index D region, 263 Airy hypothesis, 252–253, 280 I/F,59 Aitken basin, 266 β-effect, 109 albedo γ -ray fluorescence, 571 Bond albedo, 58, 77, 144 3He, 386 geometric albedo, 59 ν6 resonance, 581 giant planets, 77 monochromatic albedo, 58 ’a’a, 168f, 168 terrestrial panets, 77–78 ablation, 184 albite, 162, 239 absorption, 67 Aleutan islands, 167 absorption coefficient, 67, 71 Alfven´ velocity; see velocity absorption line, 85 Alfven´ waves, 291, 306 accretion zone, 534 ALH84001, 342 achondrites, 337, 339, 358 allotropes, 217 eucrite, 339 α decay, 352, 365 HED, 358 Amalthea, 227f, 455, 484 acid rain, 194 amorphous ice, 412, 438 activation energy, 127 Ampere’s law, 290 active region, 283 amphibole, 154 active sector, 317, 319 andesite, 156f Adams–Williams equation, 261, 281 angle of repose, 163 adaptive optics (AO), 104, 194, 494, 568f, 568–569 angular momentum, 521 adiabatic invariants anhydrous rock, 550 first invariant, 297 anion, 153 second invariant, 297–298 anomalous cosmic rays, 311f, 312 third invariant, 298 anorthite, 162, 197 adiabatic lapse rate, 63–64, 80–81, 149 anorthosite, 197 dry, 64, 80 ansa, 459 giant planets, 77 antapex, 189 superadiabatic, 64, 70, 111 Antarctica, 214 wet, 101–102 anticyclone, 111f, 112 Adrastea, 225, 227f, 454f, 484 antipode, 183, 197, 316 advection, 61 apex, 189 advective derivative, 108 Apollo program, 16 aeolian processes, 173 Apollo spacecraft, 95, 185, 196–197, 267f, 316, 341 aerodynamic drag, 49, 55, 102, 347–348, 416 apparition, 407 aerogel, 432f, 432 aqueous alteration, 401 AGB star (asymptotic giant branch), 527 arachnoid, 201, 202f agregates, 528 Archimedean spiral, 287f airglow, 135 Archimedes principle, 251 625 © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-09161-0 - Planetary Sciences: Updated Second Edition Imke de Pater and Jack J. -

Extra-Solar Planetary Systems

From the Academy Extra-solar planetary systems Joan Najita*†, Willy Benz‡, and Artie Hatzes§ *National Optical Astronomy Observatories, 950 North Cherry Avenue, Tucson, AZ 85719; ‡Physikalisches Institut, Universita¨t Bern, Sidlerstrasse 5, Ch-3012, Bern, Switzerland; and §McDonald Observatory, University of Texas, Austin, TX 78712 he discovery of extra-solar planets has captured the imagi- Table 1. Properties of extra-solar planet candidates Tnation and interest of the public and scientific communities K, alike, and for the same reasons: we are all want to know the Parent star M sin i Period, days a,AU e m⅐sϪ1 answers to questions such as ‘‘Where do we come from?’’ and ‘‘Are we alone?’’ Throughout this century, popular culture has HD 187123 0.52 3.097 0.042 0. 72. presumed the existence of other worlds and extra-terrestrial Bootis 3.64 3.3126 0.042 0. 469. intelligence. As a result, the annals of popular culture are filled HD 75289 0.42 3.5097 0.046 0. 54. with thoughts on what extra-solar planets and their inhabitants 51 Peg 0.44 4.2308 0.051 0.01 56. are like. And now toward the end of the century, astronomers And b 0.71 4.617 0.059 0.034 73.0 have managed to confirm at least one aspect of this speculative HD 217107 1.28 7.11 0.07 0.14 140. search for understanding in finding convincing evidence of Gliese 86 3.6 15.83 0.11 0.042 379. planets beyond the solar system. 1 Cancri 0.85 14.656 0.12 0.03 75.8 The discovery of extra-solar planets has brought with it a HD 195019 3.43 18.3 0.14 0.05 268. -

Correlations Between the Stellar, Planetary, and Debris Components of Exoplanet Systems Observed by Herschel⋆

A&A 565, A15 (2014) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201323058 & c ESO 2014 Astrophysics Correlations between the stellar, planetary, and debris components of exoplanet systems observed by Herschel J. P. Marshall1,2, A. Moro-Martín3,4, C. Eiroa1, G. Kennedy5,A.Mora6, B. Sibthorpe7, J.-F. Lestrade8, J. Maldonado1,9, J. Sanz-Forcada10,M.C.Wyatt5,B.Matthews11,12,J.Horner2,13,14, B. Montesinos10,G.Bryden15, C. del Burgo16,J.S.Greaves17,R.J.Ivison18,19, G. Meeus1, G. Olofsson20, G. L. Pilbratt21, and G. J. White22,23 (Affiliations can be found after the references) Received 15 November 2013 / Accepted 6 March 2014 ABSTRACT Context. Stars form surrounded by gas- and dust-rich protoplanetary discs. Generally, these discs dissipate over a few (3–10) Myr, leaving a faint tenuous debris disc composed of second-generation dust produced by the attrition of larger bodies formed in the protoplanetary disc. Giant planets detected in radial velocity and transit surveys of main-sequence stars also form within the protoplanetary disc, whilst super-Earths now detectable may form once the gas has dissipated. Our own solar system, with its eight planets and two debris belts, is a prime example of an end state of this process. Aims. The Herschel DEBRIS, DUNES, and GT programmes observed 37 exoplanet host stars within 25 pc at 70, 100, and 160 μm with the sensitiv- ity to detect far-infrared excess emission at flux density levels only an order of magnitude greater than that of the solar system’s Edgeworth-Kuiper belt. Here we present an analysis of that sample, using it to more accurately determine the (possible) level of dust emission from these exoplanet host stars and thereafter determine the links between the various components of these exoplanetary systems through statistical analysis. -

Les Exoplanètes

LESLES EXOPLANEXOPLANÈÈTESTES Introduction Les différentes méthodes de détection Le télescope spatial Kepler Résultats et typologie GAP 47 • Olivier Sabbagh • Avril 2016 Les exoplanètes I Introduction Une exoplanète, ou planète extrasolaire, est une planète située en dehors du système solaire, c’est à dire une planète qui est en orbite autour d’une étoile autre que notre Soleil. L'existence de planètes situées en dehors du Système solaire est évoquée dès le XVIe siècle par Giordano Bruno. Ce moine novateur et provocateur du XVI° siècle a eu des intuitions foudroyantes qu’il assénait avec force et conviction, en opposition farouche contre le dogme du géocentrisme qui prévalait depuis Aristote et Ptolémée. Son entêtement lui vaudra le bûcher pour hérésie en 1600. Voir le paragraphe qui lui est consacré dans notre document « une histoire de l’astronomie ». Dès 1584 (Le Banquet des cendres), Bruno adhère, contre la cosmologie d'Aristote, à la cosmologie de Copernic (1543), à l'héliocentrisme : double mouvement des planètes sur elles-mêmes et autour du Soleil, au centre. Mais Bruno va plus loin : il veut renoncer à l'idée de centre : « Il n'y a aucun astre au milieu de l'univers, parce que celui-ci s'étend également dans toutes ses directions ». Chaque étoile est un soleil semblable au nôtre, et autour de chacune d'elles tournent d'autres planètes, invisibles à nos yeux, mais qui existent. « Il est donc d'innombrables soleils et un nombre infini de terres tournant autour de ces soleils, à l'instar des sept « terres » [la Terre, la Lune, les cinq planètes alors connues : Mercure, Vénus, Mars, Jupiter, Saturne] que nous voyons tourner autour du Soleil qui nous est proche ». -

Simulating (Sub)Millimeter Observations of Exoplanet Atmospheres in Search of Water

University of Groningen Kapteyn Astronomical Institute Simulating (Sub)Millimeter Observations of Exoplanet Atmospheres in Search of Water September 5, 2018 Author: N.O. Oberg Supervisor: Prof. Dr. F.F.S. van der Tak Abstract Context: Spectroscopic characterization of exoplanetary atmospheres is a field still in its in- fancy. The detection of molecular spectral features in the atmosphere of several hot-Jupiters and hot-Neptunes has led to the preliminary identification of atmospheric H2O. The Atacama Large Millimiter/Submillimeter Array is particularly well suited in the search for extraterrestrial water, considering its wavelength coverage, sensitivity, resolving power and spectral resolution. Aims: Our aim is to determine the detectability of various spectroscopic signatures of H2O in the (sub)millimeter by a range of current and future observatories and the suitability of (sub)millimeter astronomy for the detection and characterization of exoplanets. Methods: We have created an atmospheric modeling framework based on the HAPI radiative transfer code. We have generated planetary spectra in the (sub)millimeter regime, covering a wide variety of possible exoplanet properties and atmospheric compositions. We have set limits on the detectability of these spectral features and of the planets themselves with emphasis on ALMA. We estimate the capabilities required to study exoplanet atmospheres directly in the (sub)millimeter by using a custom sensitivity calculator. Results: Even trace abundances of atmospheric water vapor can cause high-contrast spectral ab- sorption features in (sub)millimeter transmission spectra of exoplanets, however stellar (sub) millime- ter brightness is insufficient for transit spectroscopy with modern instruments. Excess stellar (sub) millimeter emission due to activity is unlikely to significantly enhance the detectability of planets in transit except in select pre-main-sequence stars.