Educational Inequality and Intergenerational Mobility in Latin America: a New Database

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hypothesis Testing with Two Categorical Variables 203

Chapter 10 distribute or Hypothesis Testing With Two Categoricalpost, Variables Chi-Square copy, Learning Objectives • Identify the correct types of variables for use with a chi-square test of independence. • Explainnot the difference between parametric and nonparametric statistics. • Conduct a five-step hypothesis test for a contingency table of any size. • Explain what statistical significance means and how it differs from practical significance. • Identify the correct measure of association for use with a particular chi-square test, Doand interpret those measures. • Use SPSS to produce crosstabs tables, chi-square tests, and measures of association. 202 Part 3 Hypothesis Testing Copyright ©2016 by SAGE Publications, Inc. This work may not be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means without express written permission of the publisher. he chi-square test of independence is used when the independent variable (IV) and dependent variable (DV) are both categorical (nominal or ordinal). The chi-square test is member of the family of nonparametric statistics, which are statistical Tanalyses used when sampling distributions cannot be assumed to be normally distributed, which is often the result of the DV being categorical rather than continuous (we will talk in detail about this). Chi-square thus sits in contrast to parametric statistics, which are used when DVs are continuous and sampling distributions are safely assumed to be normal. The t test, analysis of variance, and correlation are all parametric. Before going into the theory and math behind the chi-square statistic, read the Research Examples for illustrations of the types of situations in which a criminal justice or criminology researcher would utilize a chi- square test. -

Esomar/Grbn Guideline for Online Sample Quality

ESOMAR/GRBN GUIDELINE FOR ONLINE SAMPLE QUALITY ESOMAR GRBN ONLINE SAMPLE QUALITY GUIDELINE ESOMAR, the World Association for Social, Opinion and Market Research, is the essential organisation for encouraging, advancing and elevating market research: www.esomar.org. GRBN, the Global Research Business Network, connects 38 research associations and over 3500 research businesses on five continents: www.grbn.org. © 2015 ESOMAR and GRBN. Issued February 2015. This Guideline is drafted in English and the English text is the definitive version. The text may be copied, distributed and transmitted under the condition that appropriate attribution is made and the following notice is included “© 2015 ESOMAR and GRBN”. 2 ESOMAR GRBN ONLINE SAMPLE QUALITY GUIDELINE CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION AND SCOPE ................................................................................................... 4 2 DEFINITIONS .............................................................................................................................. 4 3 KEY REQUIREMENTS ................................................................................................................ 6 3.1 The claimed identity of each research participant should be validated. .................................................. 6 3.2 Providers must ensure that no research participant completes the same survey more than once ......... 8 3.3 Research participant engagement should be measured and reported on ............................................... 9 3.4 The identity and personal -

Lecture 1: Why Do We Use Statistics, Populations, Samples, Variables, Why Do We Use Statistics?

1pops_samples.pdf Michael Hallstone, Ph.D. [email protected] Lecture 1: Why do we use statistics, populations, samples, variables, why do we use statistics? • interested in understanding the social world • we want to study a portion of it and say something about it • ex: drug users, homeless, voters, UH students Populations and Samples Populations, Sampling Elements, Frames, and Units A researcher defines a group, “list,” or pool of cases that she wishes to study. This is a population. Another definition: population = complete collection of measurements, objects or individuals under study. 1 of 11 sample = a portion or subset taken from population funny circle diagram so we take a sample and infer to population Why? feasibility – all MD’s in world , cost, time, and stay tuned for the central limits theorem...the most important lecture of this course. Visualizing Samples (taken from) Populations Population Group you wish to study (Mostly made up of “people” in the Then we infer from sample back social sciences) to population (ALWAYS SOME ERROR! “sampling error” Sample (a portion or subset of the population) 4 This population is made up of the things she wishes to actually study called sampling elements. Sampling elements can be people, organizations, schools, whales, molecules, and articles in the popular press, etc. The sampling element is your exact unit of analysis. For crime researchers studying car thieves, the sampling element would probably be individual car thieves – or theft incidents reported to the police. For drug researchers the sampling elements would be most likely be individual drug users. Inferential statistics is truly the basis of much of our scientific evidence. -

Assessment of Socio-Demographic Sample Composition in ESS Round 61

Assessment of socio-demographic sample composition in ESS Round 61 Achim Koch GESIS – Leibniz Institute for the Social Sciences, Mannheim/Germany, June 2016 Contents 1. Introduction 2 2. Assessing socio-demographic sample composition with external benchmark data 3 3. The European Union Labour Force Survey 3 4. Data and variables 6 5. Description of ESS-LFS differences 8 6. A summary measure of ESS-LFS differences 17 7. Comparison of results for ESS 6 with results for ESS 5 19 8. Correlates of ESS-LFS differences 23 9. Summary and conclusions 27 References 1 The CST of the ESS requests that the following citation for this document should be used: Koch, A. (2016). Assessment of socio-demographic sample composition in ESS Round 6. Mannheim: European Social Survey, GESIS. 1. Introduction The European Social Survey (ESS) is an academically driven cross-national survey that has been conducted every two years across Europe since 2002. The ESS aims to produce high- quality data on social structure, attitudes, values and behaviour patterns in Europe. Much emphasis is placed on the standardisation of survey methods and procedures across countries and over time. Each country implementing the ESS has to follow detailed requirements that are laid down in the “Specifications for participating countries”. These standards cover the whole survey life cycle. They refer to sampling, questionnaire translation, data collection and data preparation and delivery. As regards sampling, for instance, the ESS requires that only strict probability samples should be used; quota sampling and substitution are not allowed. Each country is required to achieve an effective sample size of 1,500 completed interviews, taking into account potential design effects due to the clustering of the sample and/or the variation in inclusion probabilities. -

Summary of Human Subjects Protection Issues Related to Large Sample Surveys

Summary of Human Subjects Protection Issues Related to Large Sample Surveys U.S. Department of Justice Bureau of Justice Statistics Joan E. Sieber June 2001, NCJ 187692 U.S. Department of Justice Office of Justice Programs John Ashcroft Attorney General Bureau of Justice Statistics Lawrence A. Greenfeld Acting Director Report of work performed under a BJS purchase order to Joan E. Sieber, Department of Psychology, California State University at Hayward, Hayward, California 94542, (510) 538-5424, e-mail [email protected]. The author acknowledges the assistance of Caroline Wolf Harlow, BJS Statistician and project monitor. Ellen Goldberg edited the document. Contents of this report do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Bureau of Justice Statistics or the Department of Justice. This report and others from the Bureau of Justice Statistics are available through the Internet — http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov/bjs Table of Contents 1. Introduction 2 Limitations of the Common Rule with respect to survey research 2 2. Risks and benefits of participation in sample surveys 5 Standard risk issues, researcher responses, and IRB requirements 5 Long-term consequences 6 Background issues 6 3. Procedures to protect privacy and maintain confidentiality 9 Standard issues and problems 9 Confidentiality assurances and their consequences 21 Emerging issues of privacy and confidentiality 22 4. Other procedures for minimizing risks and promoting benefits 23 Identifying and minimizing risks 23 Identifying and maximizing possible benefits 26 5. Procedures for responding to requests for help or assistance 28 Standard procedures 28 Background considerations 28 A specific recommendation: An experiment within the survey 32 6. -

Chapter 3: Simple Random Sampling and Systematic Sampling

Chapter 3: Simple Random Sampling and Systematic Sampling Simple random sampling and systematic sampling provide the foundation for almost all of the more complex sampling designs that are based on probability sampling. They are also usually the easiest designs to implement. These two designs highlight a trade-off inherent in all sampling designs: do we select sample units at random to minimize the risk of introducing biases into the sample or do we select sample units systematically to ensure that sample units are well- distributed throughout the population? Both designs involve selecting n sample units from the N units in the population and can be implemented with or without replacement. Simple Random Sampling When the population of interest is relatively homogeneous then simple random sampling works well, which means it provides estimates that are unbiased and have high precision. When little is known about a population in advance, such as in a pilot study, simple random sampling is a common design choice. Advantages: • Easy to implement • Requires little advance knowledge about the target population Disadvantages: • Imprecise relative to other designs if the population is heterogeneous • More expensive to implement than other designs if entities are clumped and the cost to travel among units is appreciable How it is implemented: • Select n sample units at random from N available in the population All units within the population must have the same probability of being selected, therefore each and every sample of size n drawn from the population has an equal chance of being selected. There are many strategies available for selecting a random sample. -

Indicators for Support for Economic Integration in Latin America

Pepperdine Policy Review Volume 11 Article 9 5-10-2019 Indicators for Support for Economic Integration in Latin America Will Humphrey Pepperdine University, School of Public Policy, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/ppr Recommended Citation Humphrey, Will (2019) "Indicators for Support for Economic Integration in Latin America," Pepperdine Policy Review: Vol. 11 , Article 9. Available at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/ppr/vol11/iss1/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Public Policy at Pepperdine Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pepperdine Policy Review by an authorized editor of Pepperdine Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. Indicators for Support for Economic Integration in Latin America By: Will Humphrey Abstract Regionalism is a common phenomenon among many countries who share similar infrastructures, economic climates, and developmental challenges. Latin America is no different and has experienced the urge to economically integrate since World War II. Research literature suggests that public opinion for economic integration can be a motivating factor in a country’s proclivity to integrate with others in its geographic region. People may support integration based on their perception of other countries’ models or based on how much they feel their voice has political value. They may also fear it because they do not trust outsiders and the mixing of societies that regionalism often entails. Using an ordered probit model and data from the 2018 Latinobarómetro public opinion survey, I find that the desire for a more alike society, opinion on the European Union, and the nature of democracy explain public support for economic integration. -

Categorical Data Analysis

Categorical Data Analysis Related topics/headings: Categorical data analysis; or, Nonparametric statistics; or, chi-square tests for the analysis of categorical data. OVERVIEW For our hypothesis testing so far, we have been using parametric statistical methods. Parametric methods (1) assume some knowledge about the characteristics of the parent population (e.g. normality) (2) require measurement equivalent to at least an interval scale (calculating a mean or a variance makes no sense otherwise). Frequently, however, there are research problems in which one wants to make direct inferences about two or more distributions, either by asking if a population distribution has some particular specifiable form, or by asking if two or more population distributions are identical. These questions occur most often when variables are qualitative in nature, making it impossible to carry out the usual inferences in terms of means or variances. For such problems, we use nonparametric methods. Nonparametric methods (1) do not depend on any assumptions about the parameters of the parent population (2) generally assume data are only measured at the nominal or ordinal level. There are two common types of hypothesis-testing problems that are addressed with nonparametric methods: (1) How well does a sample distribution correspond with a hypothetical population distribution? As you might guess, the best evidence one has about a population distribution is the sample distribution. The greater the discrepancy between the sample and theoretical distributions, the more we question the “goodness” of the theory. EX: Suppose we wanted to see whether the distribution of educational achievement had changed over the last 25 years. We might take as our null hypothesis that the distribution of educational achievement had not changed, and see how well our modern-day sample supported that theory. -

Synergy of Quantitative and Qualitative Marketing Research − Capi and Observation Diary1

ECONOMETRICS. EKONOMETRIA Advances in Applied Data Analysis Year 2018, Vol. 22, No. 1 ISSN 1507-3866; e-ISSN 2449-9994 SYNERGY OF QUANTITATIVE AND QUALITATIVE MARKETING RESEARCH − CAPI AND OBSERVATION DIARY1 Marcin Lipowski, Zbigniew Pastuszak, Ilona Bondos Maria Curie-Skłodowska University in Lublin, Lublin, Poland e-mails: [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] © 2018 Marcin Lipowski, Zbigniew Pastuszak, Ilona Bondos This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- -NoDerivs license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/) DOI: 10.15611/eada.2018.1.04 JEL Classification: M31, C83 Abstract: The purpose of the publication is to indicate the need for a well thought-out combination of quantitative marketing research with qualitative research. The result of this research approach should be a fuller understanding of the research problem and the ability to interpret results more closely, while maintaining the reliability of the whole research process. In the theoretical part of the article, the essence of quantitative and qualitative research, with particular emphasis on the limitations and strengths of both research approaches, is presented. The increasing popularity of qualitative research does not absolve researchers from the prudent attitude towards the whole marketing research process − including the need to verify hypotheses or research questions. Excessive simplification in the approach to qualitative research can distort the essence of marketing research. In the empirical part of the article, the authors presented an example of combining quantitative marketing research with qualitative research − for this purpose, the results of their research will be used (scientific grant from National Science Centre). -

Lecture 8: Sampling Methods

Lecture 8: Sampling Methods Donglei Du ([email protected]) Faculty of Business Administration, University of New Brunswick, NB Canada Fredericton E3B 9Y2 Donglei Du (UNB) ADM 2623: Business Statistics 1 / 30 Table of contents 1 Sampling Methods Why Sampling Probability vs non-probability sampling methods Sampling with replacement vs without replacement Random Sampling Methods 2 Simple random sampling with and without replacement Simple random sampling without replacement Simple random sampling with replacement 3 Sampling error vs non-sampling error 4 Sampling distribution of sample statistic Histogram of the sample mean under SRR 5 Distribution of the sample mean under SRR: The central limit theorem Donglei Du (UNB) ADM 2623: Business Statistics 2 / 30 Layout 1 Sampling Methods Why Sampling Probability vs non-probability sampling methods Sampling with replacement vs without replacement Random Sampling Methods 2 Simple random sampling with and without replacement Simple random sampling without replacement Simple random sampling with replacement 3 Sampling error vs non-sampling error 4 Sampling distribution of sample statistic Histogram of the sample mean under SRR 5 Distribution of the sample mean under SRR: The central limit theorem Donglei Du (UNB) ADM 2623: Business Statistics 3 / 30 Why sampling? The physical impossibility of checking all items in the population, and, also, it would be too time-consuming The studying of all the items in a population would not be cost effective The sample results are usually adequate The destructive nature of certain tests Donglei Du (UNB) ADM 2623: Business Statistics 4 / 30 Sampling Methods Probability Sampling: Each data unit in the population has a known likelihood of being included in the sample. -

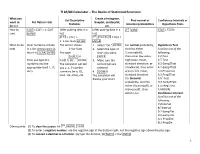

TI 83/84 Calculator – the Basics of Statistical Functions

TI 83/84 Calculator – The Basics of Statistical Functions What you Create a histogram, Get Descriptive Find normal or Confidence Intervals or want to Put Data in Lists boxplot, scatterplot, Statistics binomial probabilities Hypothesis Tests do >>> etc. How to STAT > EDIT > 1: EDIT [after putting data in a [after putting data in a 2nd VARS STAT > TESTS start ENTER list] list] STAT > CALC > 2nd STAT PLOT 1:Plot 1 1: 1-Var Stats ENTER ENTER What to do Clear numbers already The screen shows: 1. Select “On,” ENTER For normal probability, Hypothesis Test: next in a list: Arrow up to L1, 1-Var Stats 2. Select the type of scroll to either Scroll to one of the then hit CLEAR, ENTER. You type: chart you want, 2: normalcdf(, following: 2nd L1 or ENTER then enter low value, 1:Z-Test Then just type the 2nd L2, etc. ENTER 3. Make sure the high value, mean, 2:T-Test numbers into the The calculator will tell correct lists are standard deviation; or 3:2-SampZTest appropriate list (L1, L2, you ̅, s, 5-number selected 3:invNorm(, then enter 4:2-SampTTest etc.) summary (min, Q1, 4. ZOOM 9 area to left, mean, 5:1-PropZTest med, Q3, max), etc. The calculator will standard deviation. 6:2-PropZTest 2 display your chart For binomial C:X -Test probability, scroll to D:2-SampFTest either 0:binompdf(, or E:LinRegTTest A:binomcdf( , then F:ANOVA( enter n,p,x. Confidence Interval: Scroll to one of the following: 7:ZInterval 8:TInterval 9:2-SampZInt 0:2-SampTInt A:1-PropZInt B:2-PropZIn Other points: (1) To clear the screen, hit 2nd, MODE, CLEAR (2) To enter a negative number, use the negative sign at the bottom right, not the negative sign above the plus sign. -

Example Populations and Samples

Example Two strains of mice: A and B. Measure cytokine IL10 (in males all the same age) after treatment. A ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● B ● ● ● ● ● ●●● 500 1000 1500 2000 2500 IL10 A ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● B ● ● ● ●● ●●● 500 1000 1500 2000 2500 IL10 (on log scale) Point: We’re not interested in these particular mice, but in as- pects of the distributions of IL10 values in the two strains. 1 Populations and samples We are interested in the distribution of measurements in the underlying (possibly hypothetical) population. Examples: • Infinite number of mice from strain A; cytokine response to treatment. • All T cells in a person; respond or not to an antigen. • All possible samples from the Baltimore water supply; concen- tration of cryptospiridium. • All possible samples of a particular type of cancer tissue; ex- pression of a certain gene. We can’t see the entire population (whether it is real or hypothetical), but we can see a random sample of the population (perhaps a set of independent, replicated measurements). 2 Parameters The object of our interest is the population distribution or, in particular, certain numerical attributes of the population distribution (called parameters). Population distribution Examples: • mean • median • SD • proportion = 1 σ • proportion > 40 µ • geometric mean 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 • 95th percentile Parameters are usually assigned greek letters (like θ, µ, and σ). 3 Sample data We make n independent measurements (or draw a random sample of size n). This gives X 1, X 2,..., X n independent and identically distributed (iid), following the population distribution. Statistic: A numerical summary (function) of the X’s (that is, of the data).