Classical Music Radio Programming and Listening Trends

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proposed Final Judgment: U.S. V. Entercom Communications Corp

Case 1:17-cv-02268 Document 2-1 Filed 11/01/17 Page 1 of 20 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Plaintiff, v. ENTERCOM COMMUNICATIONS CORP. and CBS CORPORATION, Defendants. PROPOSED FINAL JUDGMENT WHEREAS, Plaintiff, United States of America, filed its Complaint on November 1, 2017, the United States and defendants Entercom Communications Corp. and CBS Corporation, by their respective attorneys, have consented to the entry of this Final Judgment without trial or adjudication of any issue of fact or law, and without this Final Judgment constituting any evidence against or admission by any party regarding any issue of fact or law; AND WHEREAS, defendants agree to be bound by the provisions of this Final Judgment pending its approval by the Court; AND WHEREAS, the essence of this Final Judgment is the prompt and certain divestiture of certain rights or assets by the defendants to assure that competition is not substantially lessened; AND WHEREAS, the United States requires defendants to make certain divestitures for the purpose of remedying the loss of competition alleged in the Complaint; Case 1:17-cv-02268 Document 2-1 Filed 11/01/17 Page 2 of 20 AND WHEREAS, defendants have represented to the United States that the divestitures required below can and will be made, and that defendants will later raise no claim of hardship or difficulty as grounds for asking the Court to modify any of the divestiture provisions contained below; NOW THEREFORE, before any testimony is taken, without trial or adjudication of any issue of fact or law, and upon consent of the parties, it is ORDERED, ADJUDGED, AND DECREED: I. -

I Mmmmmmm I I Mmmmmmmmm I M I M I

PUBLIC DISCLOSURE COPY Return of Private Foundation OMB No. 1545-0052 Form 990-PF I or Section 4947(a)(1) Trust Treated as Private Foundation À¾µ¸ Do not enter social security numbers on this form as it may be made public. Department of the Treasury I Internal Revenue Service Information about Form 990-PF and its separate instructions is at www.irs.gov/form990pf. Open to Public Inspection For calendar year 2014 or tax year beginning , 2014, and ending , 20 Name of foundation A Employer identification number THE WILLIAM & FLORA HEWLETT FOUNDATION 94-1655673 Number and street (or P.O. box number if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite B Telephone number (see instructions) (650) 234 -4500 2121 SAND HILL ROAD City or town, state or province, country, and ZIP or foreign postal code m m m m m m m C If exemption application is I pending, check here MENLO PARK, CA 94025 G m m I Check all that apply: Initial return Initial return of a former public charity D 1. Foreign organizations, check here Final return Amended return 2. Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, checkm here m mand m attach m m m m m I Address change Name change computation H Check type of organization:X Section 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation E If private foundation status was terminatedm I Section 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable trust Other taxable private foundation under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here I J X Fair market value of all assets at Accounting method: Cash Accrual F If the foundation is in a 60-month terminationm I end of year (from Part II, col. -

Georgia High School Association State Football Championships Georgia High School Association State Football Championships

GEORGIA HIGH SCHOOL ASSOCIATION STATE FOOTBALL CHAMPIONSHIPS GEORGIA HIGH SCHOOL ASSOCIATION STATE FOOTBALL CHAMPIONSHIPS taBLE OF contents FEATURES 2011 State SPONSOR INDEX Letter from the Executive Director 3 Verizon 2 Georgia Dome Information 5 CHAMPionsHIPS Wilson 2 The Athletic Image 4 GPB Coverage 23 Friday, December 9 Georgia Meth Project 4 Fall Champions 25 Class AA Championship Sports Med South 4 GACA Hall of Fame 26 4:30 p.m. Buford vs. Calhoun Mizuno 16 Sportsmanship Award 27 Class AAAA Championship GA Army National Guard 16 Past State Champions 29 8:00 p.m. Lovejoy vs. Tucker Gatorade 18 Georgia EMC 18 Sports Authority 20 TEAM INFORMATION Saturday, December 10 Georgia Photographics 20 Class AAAAA Team Information 6-7 Class A Championship Marines 21 Class AAAA Team Information 8-9 1:00 p.m. Savannah Chr. vs. Landmark Chr. Choice Hotel 21 Class AAA Team Information 10-11 Class AAA Championship Musco Lighting 22 Class AA Team Information 12-13 4:30 p.m. Burke Co. vs. Peach Co. Bauerfeind 22 Class A Team Information 14-15 Class AAAAA Championship Score Atlanta 24 PlayOn Sports 26 Class AAAAA Bracket 17 8:00 p.m. Grayson vs. Walton Regions Bank 28 Class AAAA Bracket 17 All games will be televised live in HD on Georgia Public Broad- Jostens 28 Class AAA Bracket 19 casting, streamed live on GPB.org and GHSA.tv and available by Field Turf 30 radio on the Georgia News Network, which are available to GNN’s Class AA Bracket 19 statewide radio network of 115 affiliates. The games will be avail- Team IP 30 Class A Bracket 20 able On Demand at GPB.org/sports and GHSA.tv and rebroadcast Georgia Public Broadcasting 31 next week on GPB Knowledge on Atlanta Comcast channel 246 or statewide on over-the-air service at the .3 digital channel. -

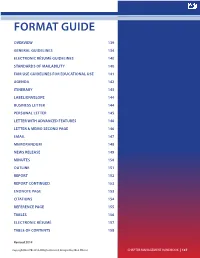

Format Guide

FORMAT GUIDE OVERVIEW 139 GENERAL GUIDELINES 134 ELECTRONIC RÉSUMÉ GUIDELINES 140 STANDARDS OF MAILABILITY 140 FAIR USE GUIDELINES FOR EDUCATIONAL USE 141 AGENDA 142 ITINERARY 143 LABEL/ENVELOPE 144 BUSINESS LETTER 144 PERSONAL LETTER 145 LETTER WITH ADVANCED FEATURES 146 LETTER & MEMO SECOND PAGE 146 EMAIL 147 MEMORANDUM 148 NEWS RELEASE 149 MINUTES 150 OUTLINE 151 REPORT 152 REPORT CONTINUED 153 ENDNOTE PAGE 153 CITATIONS 154 REFERENCE PAGE 155 TABLES 156 ELECTRONIC RÉSUMÉ 157 TABLE OF CONTENTS 158 Revised 2014 Copyright FBLA-PBL 2014. All Rights Reserved. Designed by: FBLA-PBL, Inc CHAPTER MANAGEMENT HANDBOOK | 137 138 | FBLA-PBL.ORG OVERVIEW In today’s business world, communication is consistently expressed through writing. Successful businesses require a consistent message throughout the organization. A foundation of this strategy is the use of a format guide, which enables a corporation to maintain a uniform image through all its communications. Use this guide to prepare for Computer Applications and Word Processing skill events. GENERAL GUIDELINES Font Size: 11 or 12 Font Style: Times New Roman, Arial, Calibri, or Cambria Spacing: 1 space after punctuation ending a sentence (stay consistent within the document) 1 space after a semicolon 1 space after a comma 1 space after a colon (stay consistent within the document) 1 space between state abbreviation and zip code Letters: Block Style with Open Punctuation Top Margin: 2 inches Side and Bottom Margins: 1 inch Bulleted Lists: Single space individual items; double space between items -

ANNUAL REPORT 2007 a Year of Historic Change PAGE 1 the SENTENCING PROJECT ANNUAL REPORT 2007

ANNUAL REPORT 2007 A Year of Historic Change PAGE 1 THE SENTENCING PROJECT ANNUAL REPORT 2007 A YEAR OF HISTORIC CHANGE In 2007 The Sentencing Project took full advantage of the newly emerging bipartisan movement for change occasioned by a renewed focus on evidence-based policies and concern about fiscal realities. Years of organizing by The Sentencing Project and our coalition partners created hope for reform of policies that had been challenged for years with little success. When opportunity knocked, The Sentencing Project was at the door. Historic changes were made to the patently unjust and racially biased federal sentences for crack cocaine offenses, more than twenty years after their adoption. The Sentencing Project has challenged these unfair policies for years with research to highlight the racial disparities produced by the federal mandatory sentences for crack, and the tremendous burden that families from already economically disadvantaged communities experience as a result. Change took place at nearly every point of the system. The U.S. Sentencing Commission lowered the guideline sentences for crack offenses, and subsequently made the change retroactive, making 19,500 people eligible to apply for sentence reductions that are expected to average about two years. The U.S. Supreme Court then ruled that federal judges were permitted to take into account the unfairness of the 100-to-1 quantity ratio for powder vs. crack cocaine when imposing sentences for crack offenses. Reform bills were introduced by Democrats and Republicans in both houses of Congress. The Sentencing Project’s efforts to remove barriers to voting by the more than 5 million people in the United States with felony convictions who are disenfranchised also moved forward. -

As General Managers of Public Radio Stations That Serve Millions of Americans in Communities Large and Small, Urban and Rural And;

As General Managers of Public Radio stations that serve millions of Americans in communities large and small, urban and rural and; As Producers of local, regional and national content aired by stations throughout the nation committed to telling the evolving story of America, its proud history, and its committed citizens; We are writing to express our grave concern regarding the House legislation that would prohibit stations from using any Federal funds to pay for national programming and would eliminate CPB’s Program Fund. By prohibiting the use of Federal funds in any national programming, and in particular, by eliminating the CPB Program Fund, millions of Americans will be deprived of critical national and international news, information and cultural programming that cannot be found elsewhere. Local public radio stations will no longer reliably provide the community information and context so necessary to cities and towns challenged by change and faltering economies. Institutions and projects at risk include: - Radio Bilingüe’s national program service, public radio’s principal source of Latino programming - Koahnik Public Media’ Native Voice 1, public radio’s principal source of Native American programming - Youth Media, the California-based media network of young audio and video producers and a key source of a youth voice in the mass media - The Public Insight Network, American Public media’s expanding project to bring citizen experts into public radio journalism - Independent producers who depend upon the Program Fund for money to support production of series such as StoryCorps and This I Believe - Independent organizations dedicated to innovation, training, and excellence in journalism such as the Public Radio Exchange and the Association of Independents in Radio. -

Open Your Mind with the Most Diverse Mid-Day in Public Radio

Open your mind with the most diverse mid-day in public radio. The arc of change at Local Public Radio p. 3 City Visions: Meet the Team p. 4-5 Sandip Roy on India’s Election 2014 p. 6 Smiley & West Go Out Swinging p. 8 New for 2014: Latino USA & BackStory p. 9 Winter 2014 KALW: By and for the community . COMMUNITY BROADCAST PARTNERS AIA, San Francisco • Association for Continuing Education • Berkeley Symphony Orchestra • Burton High School • East Bay Express • Global Exchange • INFORUM at The Commonwealth Club • Jewish Community Center of San Francisco • LitQuake • Mills College • New America Media • Oakland Asian Cultural Center • Osher Lifelong Learning Institute at UC Berkeley • Other Minds • outLoud Radio Radio Ambulante • San Francisco Arts Commission • San Francisco Conservatory of Music • San Quentin Prison Radio • SF Performances • Stanford Storytelling Project • StoryCorps • Youth Radio KALW VOLUNTEER PRODUCERS Rachel Altman, Wendy Baker, Sarag Bernard, Susie Britton, Sarah Cahill, Tiffany Camhi, Bob Campbell, Lisa Carmack, Lisa Denenmark, Maya de Paula Hanika, Julie Dewitt, Matt Fidler, Chuck Finney, Richard Friedman, Ninna Gaensler-Debs, Mary Goode Willis, Anne Huang, Eric Jansen, Linda Jue, Alyssa Kapnik, Carol Kocivar, Ashleyanne Krigbaum, David Latulippe, Teddy Lederer, JoAnn Mar, Martin MacClain, Daphne Matziaraki, Holly McDede, Lauren Meltzer, Charlie Mintz, Sandy Miranda, Emmanuel Nado, Marty Nemko, Erik Neumann, Edwin Okong’o, Kevin Oliver, David Onek, Joseph Pace, Liz Pfeffer, Marilyn Pittman, Mary Rees, Dana Rodriguez, -

Federal Register / Vol. 61, No. 99 / Tuesday, May 21, 1996 / Notices

25528 Federal Register / Vol. 61, No. 99 / Tuesday, May 21, 1996 / Notices DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE Closing Date, published in the Federal also purchase 74 compressed digital Register on February 22, 1996.3 receivers to receive the digital satellite National Telecommunications and Applications Received: In all, 251 service. Information Administration applications were received from 47 states, the District of Columbia, Guam, AL (Alabama) [Docket Number: 960205021±6132±02] the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, File No. 96006 CTB Alabama ETV RIN 0660±ZA01 American Samoa, and the Commission, 2112 11th Avenue South, Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Ste 400, Birmingham, AL 35205±2884. Public Telecommunications Facilities Islands. The total amount of funds Signed By: Ms. Judy Stone, APT Program (PTFP) requested by the applications is $54.9 Executive Director. Funds Requested: $186,878. Total Project Cost: $373,756. AGENCY: National Telecommunications million. Notice is hereby given that the PTFP Replace fourteen Alabama Public and Information Administration, received applications from the following Television microwave equipment Commerce. organizations. The list includes all shelters throughout the state network, ACTION: Notice, funding availability and applications received. Identification of add a shelter and wiring for an applications received. any application only indicates its emergency generator at WCIQ which receipt. It does not indicate that it has experiences AC power outages, and SUMMARY: The National been accepted for review, has been replace the network's on-line editing Telecommunications and Information determined to be eligible for funding, or system at its only production facility in Administration (NTIA) previously that an application will receive an Montgomery, Alabama. announced the solicitation of grant award. -

Broadcast Actions 5/29/2014

Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 48249 Broadcast Actions 5/29/2014 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR RENEWAL GRANTED NY BR-20140131ABV WENY 71510 SOUND COMMUNICATIONS, LLC Renewal of License. E 1230 KHZ NY ,ELMIRA Actions of: 04/29/2014 FM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR MODIFICATION OF LICENSE GRANTED OH BMLH-20140415ABD WPOS-FM THE MAUMEE VALLEY License to modify. 65946 BROADCASTING ASSOCIATION E 102.3 MHZ OH , HOLLAND Actions of: 05/23/2014 AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR RENEWAL DISMISSED NY BR-20071114ABF WRIV 14647 CRYSTAL COAST Renewal of License. COMMUNICATIONS, INC. Dismissed as moot, see letter dated 5/5/2008. E 1390 KHZ NY , RIVERHEAD Page 1 of 199 Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 48249 Broadcast Actions 5/29/2014 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N Actions of: 05/23/2014 AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR ASSIGNMENT OF LICENSE GRANTED NY BAL-20140212AEC WGGO 9409 PEMBROOK PINES, INC. Voluntary Assignment of License From: PEMBROOK PINES, INC. E 1590 KHZ NY , SALAMANCA To: SOUND COMMUNICATIONS, LLC Form 314 NY BAL-20140212AEE WOEN 19708 PEMBROOK PINES, INC. -

Radio 4 Listings for 2 – 8 May 2020 Page 1 of 14

Radio 4 Listings for 2 – 8 May 2020 Page 1 of 14 SATURDAY 02 MAY 2020 Professor Martin Ashley, Consultant in Restorative Dentistry at panel of culinary experts from their kitchens at home - Tim the University Dental Hospital of Manchester, is on hand to Anderson, Andi Oliver, Jeremy Pang and Dr Zoe Laughlin SAT 00:00 Midnight News (m000hq2x) separate the science fact from the science fiction. answer questions sent in via email and social media. The latest news and weather forecast from BBC Radio 4. Presenter: Greg Foot This week, the panellists discuss the perfect fry-up, including Producer: Beth Eastwood whether or not the tomato has a place on the plate, and SAT 00:30 Intrigue (m0009t2b) recommend uses for tinned tuna (that aren't a pasta bake). Tunnel 29 SAT 06:00 News and Papers (m000htmx) Producer: Hannah Newton 10: The Shoes The latest news headlines. Including the weather and a look at Assistant Producer: Rosie Merotra the papers. “I started dancing with Eveline.” A final twist in the final A Somethin' Else production for BBC Radio 4 chapter. SAT 06:07 Open Country (m000hpdg) Thirty years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, Helena Merriman Closed Country: A Spring Audio-Diary with Brett Westwood SAT 11:00 The Week in Westminster (m000j0kg) tells the extraordinary true story of a man who dug a tunnel into Radio 4's assessment of developments at Westminster the East, right under the feet of border guards, to help friends, It seems hard to believe, when so many of us are coping with family and strangers escape. -

99.7 Now / Kmvq-Fm Pay Your Bills

The following contest is intended for participants in the United States only and will be governed by United States laws. Do not proceed in this contest if you are not eligible or not currently located in the United States. Further eligibility restrictions are contained in the official rules below. 99.7 NOW / KMVQ-FM $5,000 SECRET SOUND OFFICIAL RULES NO PURCHASE OR PAYMENT OF ANY KIND IS NECESSARY TO ENTER OR WIN. A PURCHASE OR PAYMENT WILL NOT INCREASE AN ENTRANT’S CHANCE OF WINNING. VOID WHERE PROHIBITED BY LAW. Contest Administrator/Sponsor: KMVQ-FM, 2001 Junipero Serra Blvd., Suite 350, Daly City, CA 94014 1. HOW TO ENTER a. These rules govern the 99.7 NOW $5,000 Secret Sound (“Contest”), which is being conducted by KMVQ-FM (“Station”). The Contest begins on Monday, September 20, 2021, and ends on Friday, November 5, 2021 (“Contest Dates”). Entrants may enter on-air only. KMVQ-FM may elect at its sole discretion, to continue the contest beyond this date if it so chooses. b. To enter the Contest, entrant may enter on-air beginning on Monday, September 20, 2021, at 9:20am (PT) “Pacific Time” and ending on Friday, November 5, 2021 at 5:20pm (PT) or after $40,000 has been awarded, whichever comes first (“Entry Period”). i. To enter on-air, listen to the Station each weekday beginning on Monday, September 20, 2021, at 9:20am (PT) and ending on Friday, November 5, 2021 at 5:20pm (PT) or after $40,000 has been awarded, whichever comes first during the Entry Period for the air personality to announce the cue to call. -

Your Guide to Arts and Culture in Colorado's Pikes Peak Region

2014 - 2015 Your Guide to Arts and Culture in Colorado’s Pikes Peak Region PB Find arts listings updated daily at www.peakradar.com 1 2 3 About Us Every day, COPPeR connects residents and visitors to arts and culture to enrich the Pikes Peak region. We work strategically to ensure that cultural services reach all people and that the arts are used to positively address issues of economic development, education, tourism, regional branding and civic life. As a nonprofit with a special role in our community, we work to achieve more than any one gallery, artist or performance group can do alone. Our vision: A community united by creativity. Want to support arts and culture in far-reaching, exciting ways? Give or get involved at www.coppercolo.org COPPeR’s Staff: Andy Vick, Executive Director Angela Seals, Director of Community Partnerships Brittney McDonald-Lantzer, Peak Radar Manager Lila Pickus, Colorado College Public Interest Fellow 2013-2014 Fiona Horner, Colorado College Public Interest Fellow, Summer 2014 Katherine Smith, Bee Vradenburg Fellow, Summer 2014 2014 Board of Directors: Gary Bain Andrea Barker Lara Garritano Andrew Hershberger Sally Hybl Kevin Johnson Martha Marzolf Deborah Muehleisen (Treasurer) Nathan Newbrough Cyndi Parr Mike Selix David Siegel Brenda Speer (Secretary) Jenny Stafford (Chair) Herman Tiemens (Vice Chair) Visit COPPeR’s Office and Arts Info Space Amy Triandiflou at 121 S. Tejon St., Colo Spgs, CO 80903 Joshua Waymire or call 719.634.2204. Cover photo and all photos in this issue beginning on page 10 are by stellarpropellerstudio.com. Learn more on pg. 69. 2 Find arts listings updated daily at www.peakradar.com 3 Welcome Welcome from El Paso County The Board of El Paso County Commissioners welcomes you to Colorado’s most populous county.