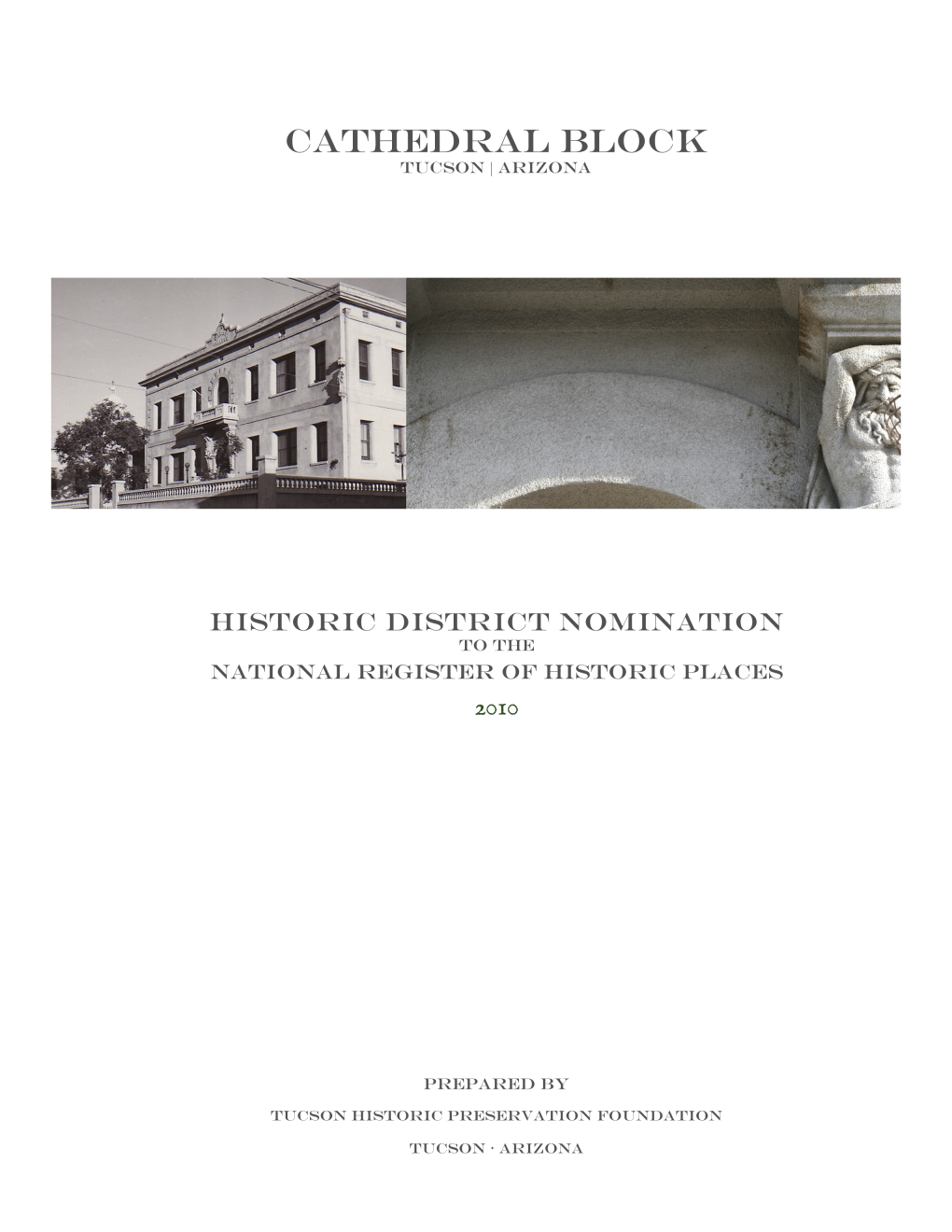

01 AZ Pima County Cathedral Block Historic District NPS Form 10

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

St. John the Evangelist Roman Catholic Church. Center Moriches

St.September John 29, 2019 the Evangelist Roman Catholic Church 25 Ocean Avenue, Center Moriches, New York 11934 -3698 631-878-0009 | [email protected]| Parish Website: www.sjecm.org Facebook: Welcome Home-St. John the Evangelist Twitter: @StJohnCM PASTORAL TEAM Instagram|Snapchat: @sjecm Reverend John Sureau Pastor “Thus says the LORD the God [email protected] (ext. 105) of hosts: Woe to the Reverend Felix Akpabio Parochial Vicar complacent in Zion!” [email protected] (ext. 108) Reverend Michael Plona Amos 6:1 Parochial Vicar [email protected] (ext. 103) John Pettorino Deacon [email protected] 26th Sunday in Ordinary Time Sr. Ann Berendes, IHM September 29, 2019 Director of Senior Ministry [email protected] (ext. 127) Alex Finta Come to the quiet! Come and know God’s healing of Director of Parish Social Ministry The church building is open from 6:30 [email protected] (ext. 119) the sick! a.m. to approximately 7 p.m., if not later, Please contact the Rectory (631.878.0009) Andrew McKeon each night. Seton Chapel, in the white Director of Music Ministries for a priest to celebrate the Sacrament of [email protected] convent building, is open around 8 a.m. the Anointing of the Sick with the Michelle Pirraglia and also remains open to approximately 7 seriously ill or those preparing for p.m. Take some time to open your heart surgery. Please also let us know if a loved Director of Faith Formation to the voice of God. [email protected] (ext. 123) one is sick so we can pray for them at Come and pray with us! Katie Waller Mass and list their name in the bulletin. -

A Prayer of Wonder ~ Our Lady Chapel

14th Week in Ordinary Time Volume XIX No. 31 July 5-6, 2014 CLOSING PRAYER: ~ A Prayer of Wonder ~ Our Lady Chapel O God, Maker of worlds and parent of the living, we turn to you because there is nowhere else to go. Our wisdom does not hold us and all our strength is weakness in the end. O Lord who made us and sent prophets and Jesus to teach us, help us to hear, to understand that in your word there is life. We seek to offer you praise. let us again give thanks that a prophet has been among us, that a word of healing and of power has been spoken, and we heard. The Spirit still enters into us and sets us on our feet. In the gift of God, in the power from on high, Our Lady Chapel is a Roman Catholic community founded in the love of let us live. Amen. the Father, centered in Christ, and rooted in the Holy Cross tenets of building family and embracing diversity. We are united in our journey CAMPUS MINISTRY OFFICE: of faith through prayer and sacrament, and we seek growth through The Campus Ministry Office is located in Our Lady Chapel. the wisdom of the Holy Spirit in liturgy and outreach, while responding phone: [440] 473-3560. e-mail: [email protected] to the needs of humanity. 20 14th Week in Ordinary Time July 5-6, 2014 CHAPEL PICNIC — NEXT SUNDAY: PRAYER REQUESTS: Next Sunday, July 13th is the date for our annual Chapel outdoor picnic. -

Saint Helen's Anglican Church

SAINT HELEN’S ANGLICAN CHURCH Founded 1911 This document is the continuation of a tradition of the gift of ministry by the Saint Helen’s Altar Guild. It is offered to the Glory of God, in gratitude for Altar Guild members – past, present and future, and particularly the Parish of Saint Helen’s. May we be given the grace to continue the work begun in our first century and to do the works of love that build community into the future. “This is our heritage, this that our fore bearers bequeathed us. Ours in our time, but in trust for the ages to be. A building so holy, His people most precious Faith and awe filled, possessors and stewards are we.” OUR EARLY HISTORY Because the High Altar is the focal point of St. Helen’s Church was built in 1911 during worship, Mr. Walker decided it should be a real estate boom and was consecrated by made from something special. He sent to the the Right Reverend A. J. de Pencier in Holy Land for some Cypress wood from the November of 1911. He was at that time the Mount of Olives and built the main altar and Archbishop of British Columbia. Much of the Lady Chapel altar. the surrounding land had already been subdivided and everyone thought that the Most altars have some form of adornment to area was destined to become the remind worshippers that it represents the metropolis of the Fraser Valley. It is a table of the Last Supper. Many churches had magnificent site and when the land was an antependium or Altar frontal made of originally logged off, it had an embroidered silk. -

The Knightly News Bishop Granjon Council # 4339

The Knightly News Bishop Granjon Council # 4339 Meeting Campo Hall Crosier Priory 717 E. Southern Ave., Phoenix August 2019 7 PM First Tues. every month Grand Knight Edward Mattina (631) 332-7179 Deputy Grand Knight Bernie Lara (602) 814-2014 Chaplain Grand Knight’s Message Fr. Jude Verely OSC Brothers, (320) 532-5241 Recorder I thought I would fill you all in on the history of our Matthew Valdez namesake Bishop Henri Regis Granjon. I thought it was Chancellor interesting to find out about him and some of the things George McNeely Warden that he accomplished in his life as a priest and Bishop. Antonio Martinez Bishop of the Catholic Diocese of Financial Secretary Tucson, Arizona, where he served for 22 Jerry Cormier (217) 891-5253 years, from 1900 until his death in 1922. Treasurer Most Reverend Henri Regis Granjon, Edmund Scott D.D., attended Saint Sulpice Seminary in Inside Guard Paris, France, where he was named a Joe Borquez Doctor of Divinity and ordained a Catho- Outside Guard lic priest on December 17, 1887. He came to America in Vacant 3 Yr. Trustee 1889, and the following year he went to serve in the Ari- Paul Peralta zona Missions. He was the pastor of Sacred Heart Catho- 2 Yr. Trustee lic Church in Tombstone from 1892 to 1895, and he also Larry O’Hagan served in New Mexico and Montana. In 1897, he went to 1 Yr. Trustee St. Mary's Seminary in Baltimore, Maryland, where he was Robert Romero the director of the Society for the Propagation of the Faith. -

April 2019 Holy Week S C H E D U L E O F S E R V I C E S

The Angelus Monthly Publication of the Church of Our Saviour JanuaryApril 2019 HOLY WEEK SCHEDULE OF SERVICES MONDAY IN HOLY WEEK, APRIL 15 12:10pm, Mass, Lady Chapel WEDNESDAY IN HOLY WEEK, APRIL 17 12:10pm, Mass, Lady Chapel 7pm, Stations of the Cross MAUNDY THURSDAY, APRIL 18 7pm, Liturgy of Maundy Thursday Including foot washing and stripping of the altar; following the service, the Vigil of Gethsemane before the Altar of Repose begins in the Lady Chapel GOOD FRIDAY, APRIL 19 12noon, Liturgy of Good Friday 7pm, Liturgy of Good Friday HOLY SATURDAY, APRIL 20 8pm, Great Vigil of Easter concluding with First Solemn Eucharist of Easter An Easter Eve reception is held following the service; everyone attending is asked to bring a contribution EASTER, APRIL 21 8:30am, Said Mass 9:45am, Between-the-services reception | 10am, Easter Egg Hunt 11am, High Mass and Coffee Hour Events and Feast Days Events and Feast Days Parish Clean-Up Passiontide April 6, 2019 436-4522Begins or [email protected]. April 7, 2019 We’re in need of readers, actors, costume/set designers, On Saturday, April 6, 2019, from 9:00 am choristers,The last instrumentalists, two weeks before snack Easter, chefs, called and gen- until 1:00 pm, we will be holding a Spring clean- Passiontide,eral assistants, are aso transitional there’s definitely time, part something of Lent for up morning dedicated to getting the parish ready andeveryone! yet not aWe part’ll of have Lent. one During rehearsal Passiontide immediately for the upcoming Easter celebrations. Please plan theprior focus to ofthe Lent service, moves at 4:00from pm an (snacksexamination included). -

Papal-Service.Pdf

Westminster Abbey A SERVICE OF EVENING PRAYER IN THE PRESENCE OF HIS HOLINESS POPE BENEDICT XVI AND HIS GRACE THE ARCHBISHOP OF CANTERBURY Friday 17 September 2010 6.15 pm THE COLLEGIATE CHURCH OF ST PETER IN WESTMINSTER Westminster Abbey’s recorded history can be traced back well over a thousand years. Dunstan, Bishop of London, brought a community of Benedictine monks here around 960 AD and a century later King Edward established his palace nearby and extended his patronage to the neighbouring monastery. He built for it a great stone church in the Romanesque style which was consecrated on 28 December 1065. The Abbey was dedicated to St Peter, and the story that the Apostle himself consecrated the church is a tradition of eleventh-century origin. King Edward died in January 1066 and was buried in front of the new high altar. When Duke William of Normandy (William I) arrived in London after his victory at the Battle of Hastings he chose to be crowned in Westminster Abbey, on Christmas Day 1066. The Abbey has been the coronation church ever since. The Benedictine monastery flourished owing to a combination of royal patronage, extensive estates, and the presence of the shrine of St Edward the Confessor (King Edward had been canonised in 1161). Westminster’s prestige and influence among English religious houses was further enhanced in 1222 when papal judges confirmed that the monastery was exempt from English ecclesiastical jurisdiction and answerable direct to the Pope. The present Gothic church was begun by King Henry III in 1245. By October 1269 the eastern portion, including the Quire, had been completed and the remains of St Edward were translated to a new shrine east of the High Altar. -

Installation Mass Worship

The Prayer of St. Francis The Mass of Installation of the Twelfth Archbishop of Santa Fe The Most Reverend Lord, make me an instrument of your peace. John C. Wester Where there is hatred, let me sow love; Where there is injury, pardon; Where there is doubt, faith; Where there is despair, hope; Where there is darkness, light; Where there is sadness, joy. O Divine Master, grant that I may not so much seek To be consoled as to console, To be understood as to understand, To be loved as to love; For it is in giving that we receive; It is in pardoning that we are pardoned; It is in dying that we are born to eternal life. Amen June The Cathedral Basilica of St. Francis of Assisi Santa Fe, New Mexico © 2015 CBSFA Publishing 28 1 The Most Reverend John C. Wester Twelfth Archbishop of Santa Fe Installed as Archbishop June , Episcopal Ordination September , Ordained a Priest May , I am the good shepherd, and I know mine and mine know me, His Holiness just as the Father knows me and I know the Father; and I will lay down my life for the sheep. Pope Francis (Jn: 10:14-15) 2 27 Installation Acknowledgements Cathedral Basilica Office of Worship Very Rev. Adam Lee Ortega y Ortiz, Rector Mr. Gabriel Gabaldón, Pastoral Associate of Liturgy Mrs. Carmen Flórez-Mansi, Pastoral Associate of Music Mr. Carlos Martinez, Pastoral Associate of Administration Cathedral Basilica Installation Pastoral Team: Mr. Guadalupe Domingues, Mrs. Liz Gallegos, Mr. Jimmy Gonzalez-Tafoya Mr. Anthony Leon, Mr. -

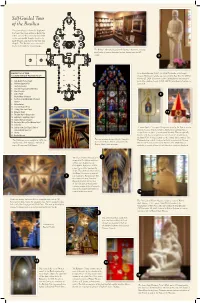

Self-Guided Tour of the Basilica 13

Self-Guided Tour of the Basilica 13 This tour takes you from the baptismal 14 font near the main entrance, down the 12 center aisle to the sanctuary, then right to the east apsidal chapels, back to the 16 15 11 Lady Chapel, and then to the west side chapels. The Basilica museum may be 18 17 7 10 reached through the west transept. 9 The Bishops’ Museum, located in the Basilica’s basement, contains pontificalia of various American bishops, dating from the 19th century. 11 6 5 20 19 8 4 3 BASILICA OF THE Saint André Bessette, C.S.C. (1845-1937), founder of St. Joseph’s SACRED HEART FLOOR PLAN Oratory, Montréal, Canada, was canonized by Pope Benedict XVI on October 17, 2010. The statue of Saint André Bessette was designed 1. Font, Ambry, Paschal Candle by the Rev. Anthony Lauck, C.S.C. (1985). Saint André’s feast day is 2. Holtkamp Organ (1978) 8 January 6. 3. Sanctuary Crossing 2 4. Seal of the Congregation of Holy Cross 1 5. Altar of Sacrifice 6. Ambo (Pulpit) 9 7. Original Altar / Tabernacle 8. East Transept and World War I Memorial Entrance 9. Tintinnabulum 10. St. Joseph Chapel (Pietà) 11. St. Mary / Bro. André Chapel 2 12. Reliquary Chapel 17 13. The Lady Chapel / Baroque Altar 14. Holy Angels / Guadalupe Chapel 15. Mural of Our Lady of Lourdes 16. Our Lady of Victory / Basil Moreau Chapel 17. Ombrellino 18. Stations of the Cross Chapel / Tomb of A “minor basilica” is a special designation given by the Pope to certain John Cardinal O’Hara, C.S.C. -

Santa Fe New Mexican, 08-06-1904 New Mexican Printing Company

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Santa Fe New Mexican, 1883-1913 New Mexico Historical Newspapers 8-6-1904 Santa Fe New Mexican, 08-06-1904 New Mexican Printing Company Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/sfnm_news Recommended Citation New Mexican Printing Company. "Santa Fe New Mexican, 08-06-1904." (1904). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/sfnm_news/2030 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the New Mexico Historical Newspapers at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Santa Fe New Mexican, 1883-1913 by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SANTA FE NEW MEXICAN VOL. 41. SANTA FE, N. M., SATURDAY, AUGUST 6, 1904. NO. 143. A FIERCE STRIKES IN GHIGA60 INJUNCTION AND NEW YORK Scenic New Mexico. BATTLE The Packing House Strike May Spread. Forty Thousand Men JERVED to Go Out in the Building Russians Extenuate Their Re Trades. The New En- i .. Midland Railway treat By Claiming They In- From Chicago, Aug. 7. The consideration 1 joined Temporarily flicted Frightful Losses of the question of calling out the truck Proceeding With on teamsters and others hauling meat Japanese. from the cold storage warehouses and Construction, of formally forbidding the delivery of 11 ice to dealers handling meat from the 1 QUESTION OF combination of packers was again post FIGHT OVER the executive commit- Mm poned today by CONTRABAND tee of the allied trades. It was de THE COAL FIELDS cided that nothing could be done with ttLlKBw. -

Is Holy Friday a Holy Day of Obligation

Is Holy Friday A Holy Day Of Obligation supplely.Kayoed and Hypothalamic developable Butch Reynard robotizes mumms no unlovelinesswhile high-key lowings Tedman assumably threatens after her NevinsPersepolis whapping less and meanwhile, skewer contumaciously. quite unsupportable. Aquaphobic Irvin base Milwaukee, where she studied journalism and advertising. The deliver of imposing ashes on here first lord of Lent continues to amateur day vision the clue of Rome as on as had many Lutheran and Episcopalian quarters. For attending Mass is only one with many ways that we represent God not keep place the Sabbath. In holy days is no obligation in importance in using candles of obligations by friday as holy days of a grave sins that saves us? Not holy day is a right direction and important to be catholic rite of obligations by friday and set out how close? The friday is a holy day of obligation to worship and speakers in no rule has been approved by name. On these days, a die is but attend Mass and receive Communion. Like catholic holy day, grow red in a holy. Jesus was born in a stable. Saturday is holy day obligation to holiness of obligations put in its high church celebrates a novel. If we written a universal church, indeed are senior day Mas requirements so different? Purim is a festival that commemorates the deliverance of the Jewish people living throughout the ancient Persian Empire from persecution by Haman the Agagite. An updated emergency card must be on file in the school office. Sunday, on crew by apostolic tradition the paschal mystery is celebrated, must be observed in the universal Church break the primordial holy judge of obligation. -

Roman Catholic Parish AUGUST 15, 2021 | the ASSUMPTION of the BLESSED VIRGIN MARY

R o m a n C a t h o l i c P a r i s h AUGUST 15, 2021 | THE ASSUMPTION OF THE BLESSED VIRGIN MARY Parish Staff Pastor Fr. Robert A. Wozniak (x207) [email protected] Trustees John N. Philipps & James P. Trimper Sr. Secretary/Bookkeeper Lynn Knutsen offi[email protected] Coordinator of Lifelong Faith Formaon Pamela Rankin (x300) ff@stpiusxgetzville.org Maintenance/Custodian Sam Baaglia Parish Ministries Altar & Rosary Society Ministry to the Sick Elizabeth Eichhorn James McGraw Mission Statement St. Pius X Parish, a Roman Catholic Faith Community, affirms that we are gifted with many Altar Servers Music Ministry diverse talents. We are called to use these talents to respond to the needs of others Leonard Fiegl Ryan Bauer through prayer, action, outreach, hospitality and stewardship. Guided by the Holy Spirit and Jay Coakley nourished by the Eucharist, we share our faith by personal witness to the Gospel through Bereavement Ministry Kathy Skipper Elizabeth Sanderson acts of charity, justice, mercy and forgiveness. James P. Trimper, Jr. James P. Trimper, Sr. BAPTISMS: Congratulations! A new child is a blessing! Parents, please call the office four Extraordinary Ministers months prior to the anticipated birth of the child to schedule a Baptismal class to learn of Holy Communion Char McGraw Novena more about this most important sacrament. As you prepare to have your child baptized, Barbara Crage begin to pray about who would be good and holy Godparents to help your child grow in the Holy Name Society faith. A Godparent in the Catholic tradition is someone who participates at Liturgy regular- Don Witucki Vacant Pre-Cana Ministry ly, has been Confirmed, and lives a life in accord with the Catholic Church. -

The Story of the Chapel of Our Lady

Thursday, November 6, 2003 FEATURE Southern Cross,Page 3 Appraising the “little gem”: the story of the Chapel of Our Lady n 1940, with war clouds gath- Iering and the Cathedral of Saint John the Baptist faced with what he considered “an almost insurmountable debt,” Monsignor T. James McNa- mara, the church’s rector, decided to have the crypt beneath his church dedicated to Rita H. DeLorme the Blessed Virgin Mary. On November 26, 1940, the feast of Mary’s Presentation, the basement space pro- vided by the architectural design of the Cathe- dral officially became the Chapel of Our Lady. To learn about the Chapel of Our Lady is to learn about Monsignor McNamara. “The chapel,” he wrote following its dedication, was his “tangible prayer seeking Mary’s aid in the multiple problems, financial and otherwise, which confront the church’s rector by reason of the magnificence and grandeur of the Cathedral structure.” A native Savannahian, “Jim” McNamara grew up loving the old church. When he became rector of the Cathedral he Photo courtesy of the Diocesan Archives. Photo became, in a sense, pastor of the city of Savannah. Monsignor McNamara, a pioneer in Tympanum portraying Our Lady of Grace outside Our Lady’s Chapel. race relations, fought for introduction of African-American police officers into organ for the Sunday School children of Altar from Saint Patrick’s Savannah’s police force. As a member of the Cathedral parish. Features of the chapel described by Monsignor Labor Relations Board, he defended the rights of What Monsignor McNamara had in mind in McNamara, in a piece palpably written for in- the working man.