Short Guide to Western Mongolia Tour

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

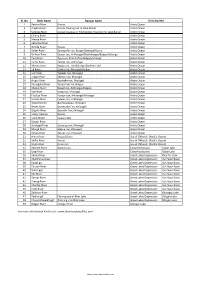

List of Rivers of Mongolia

Sl. No River Name Russian Name Draining Into 1 Yenisei River Russia Arctic Ocean 2 Angara River Russia, flowing out of Lake Baikal Arctic Ocean 3 Selenge River Сэлэнгэ мөрөн in Sükhbaatar, flowing into Lake Baikal Arctic Ocean 4 Chikoy River Arctic Ocean 5 Menza River Arctic Ocean 6 Katantsa River Arctic Ocean 7 Dzhida River Russia Arctic Ocean 8 Zelter River Зэлтэрийн гол, Bulgan/Selenge/Russia Arctic Ocean 9 Orkhon River Орхон гол, Arkhangai/Övörkhangai/Bulgan/Selenge Arctic Ocean 10 Tuul River Туул гол, Khentii/Töv/Bulgan/Selenge Arctic Ocean 11 Tamir River Тамир гол, Arkhangai Arctic Ocean 12 Kharaa River Хараа гол, Töv/Selenge/Darkhan-Uul Arctic Ocean 13 Eg River Эгийн гол, Khövsgöl/Bulgan Arctic Ocean 14 Üür River Үүрийн гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 15 Uilgan River Уйлган гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 16 Arigiin River Аригийн гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 17 Tarvagatai River Тарвагтай гол, Bulgan Arctic Ocean 18 Khanui River Хануй гол, Arkhangai/Bulgan Arctic Ocean 19 Ider River Идэр гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 20 Chuluut River Чулуут гол, Arkhangai/Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 21 Suman River Суман гол, Arkhangai Arctic Ocean 22 Delgermörön Дэлгэрмөрөн, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 23 Beltes River Бэлтэсийн Гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 24 Bügsiin River Бүгсийн Гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 25 Lesser Yenisei Russia Arctic Ocean 26 Kyzyl-Khem Кызыл-Хем Arctic Ocean 27 Büsein River Arctic Ocean 28 Shishged River Шишгэд гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 29 Sharga River Шарга гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 30 Tengis River Тэнгис гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 31 Amur River Russia/China -

INFLUENCE of SOIL-ECOLOGICAL CONDITIONS on VEGETATION ZONATION in a WESTERN MONGOLIAN LAKE SHORE- SEMI-DESERT ECOTONE with 6 Figures, 4 Tables and 4 Photos

72 Erdkunde Band 61/2007 INFLUENCE OF SOIL-ECOLOGICAL CONDITIONS ON VEGETATION ZONATION IN A WESTERN MONGOLIAN LAKE SHORE- SEMI-DESERT ECOTONE With 6 figures, 4 tables and 4 photos ANDREA STRAUSS and UDO SCHICKHOFF Keywords: Vegetation geography, soil geography, environmental change, Central Asia, semidesert environments Keywords: Vegetationsgeographie, Bodengeographie, Umweltforschung, Zentralasien, aride Räume Zusammenfassung: Der Einfluss bodenökologischer Bedingungen auf die Vegetationszonierung in einem Seeufer-Halb- wüsten-Ökoton der westlichen Mongolei Das Becken der Großen Seen in der Westmongolei ist geprägt von ausgedehnten Wüsten-, Halbwüsten- und Steppen- arealen sowie von Seen und umgebenden einzigartigen Feuchtgebieten. Diese Feuchtgebiete sind bedeutende Elemente der Landschaftsökosysteme semi-arider und arider Räume. Andererseits ist die Kenntnis selbst grundlegender Ökosystemkompo- nenten wie Vegetation und Böden noch sehr lückenhaft. Das Ziel der vorliegenden landschaftsökologischen Studie entlang eines Seeufer-Halbwüsten-Ökotons war es, das klein- räumige Muster von Standortfaktoren entlang eines ausgeprägten Umweltgradienten sowie den Einfluss dieses Musters auf die Vegetationszonierung zu analysieren. Um die Veränderungen in dem Übergangsbereich zwischen aquatischen und terres- trischen Lebensräumen adäquat zu erfassen, wurden die Daten mit einem Transekt-Ansatz aufgenommen. Pflanzengesell- schaften wurden nach der Braun-Blanquet-Methode klassifiziert. Die Vegetations- und Bodendaten wurden einer Detrended Correspondence -

UYGHUR STUDIES in CENTRAL ASIA: a Historical Review

UYGHUR STUDIES IN CENTRAL ASIA 3 ABLET KAMALOV UYGHUR STUDIES IN CENTRAL ASIA: A Historical Review INTRODUCTION The Uyghurs, a Turkic people comprising a major part of the population of the Xinjiang-Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR), China, also have sizable communities in the former Soviet Central Asian Republics, espe- cially in Kazakhstan, where they numbered 220,000 in 1999 (altogether the Uyghur population in the newly independent states numbers more than 300,000). The Central Asian Uyghur community played a signifi- cant role in the Uyghur nation-building process as well as in Soviet- Chinese relations during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The Soviet authorities used the Uyghurs as a tool in their policy toward Xinjiang (Eastern Turkistan) and for that purpose provided special sup- port for the development of Uyghur culture in Central Asia. A significant part of that policy was the development of Uyghur studies in Central Asia, particularly in Kazakhstan, which became a cultural center for the Soviet Uyghurs. Uyghur studies covers mostly the research done in the sphere of language, literature, history, and culture (art, music, etc). This article will examine the history of Uyghur studies in Soviet Central Asia and outline its trends. 4 KAMALOV THE MAIN STAGES The Initial Stage (1920–1945) The earliest research on Uyghurs conducted in Central Asia exhibited mostly a practical character. The purpose was to pursue specific goals of Soviet national policy aimed at the creation of new socialist “nations” in the region. The Uyghurs, along with other peoples, were recognized by the Soviet state as a “nation” during the period of national delimitation and demarcation in Central Asia during the early 1920s, just after the establishment of Bolshevik power. -

Archaeological Investigations of Xiongnu Sites in the Tamir River

Archaeological Investigations of Xiongnu Sites in the Tamir River Valley Results of the 2005 Joint American-Mongolian Expedition to Tamiryn Ulaan Khoshuu, Ogii nuur, Arkhangai aimag, Mongolia David E. Purcell and Kimberly C. Spurr Flagstaff, Arizona (USA) During the summer of 2005 an archaeological investigations, and What is known points to this area archaeological expedition jointly their results, are the focus of this as one of the most important mounted by the Silkroad Foun- article, which is a preliminary and cultural regions in the world, a fact dation of Saratoga, California, incomplete record of the project recently recognized by the U.S.A. and the Mongolian National findings. Not all of the project data UNESCO through designation of University, Ulaanbataar, investi- — including osteological analysis of the Orkhon Valley as a World gated two sites near the the burials, descriptions or maps Heritage Site in 2004 (UNESCO confluence of the Tamir River with of the graves, or analyses of the 2006). Archaeological remains the Orkhon River in the Arkhangai artifacts — is available as of this indicate the region has been aimag of central Mongolia (Fig. 1). writing. Consequently, the greater occupied since the Paleolithic (circa The expedition was permitted emphasis falls on one of the two 750,000 years before present), (Registration Number 8, issued sites. It is hoped that through the with Neolithic sites found in great June 23, 2005) by the Ministry of Silkroad Foundation, the many numbers. As early as the Neolithic Education, Culture and Science of different collections from this period a pattern developed in Mongolia. The project had multiple project can be reunited in a which groups moved southward goals: archaeological investiga- scholarly publication. -

Spring 2010 Far Horizons Newsletter

NEWSLETTER FAR HORIZONS ARCHAEOLOGICAL & CULTURAL TRIPS Volume 15, Number 1 • Spring 2010 Published Erratically by Far Horizons • P.O. Box 2546 • San Anselmo, CA 94979 USA (800) 552-4575 • (415) 482-8400 • fax (415) 482-8495 • www.farhorizons.com • email: [email protected] Dear Travelers, I am delighted to dedicate this newsletter to those participants who travel with Far Horizons repeatedly – thank you! In fact, we have included articles from some of our frequent travelers in which they eloquently describe their experiences exploring remarkable destinations with our fabulous study leaders. Don’t miss these evocative accounts of their adventures. There are only a very few spaces remaining on the September trip led by Professor Jonathan Phillips of History Channel fame. I am so pleased that people are excited about our Crusades trip! By the way, look for Professor Jonathan Phillips’ new book, Holy Warriors: A Modern History of the Crusades. We plan to design more itineraries relating to the medieval era, so keep watching our webpage. Are you a Bob Brier enthusiast (do you know anyone who isn’t!)? There are still a few spaces left on Bob’s Egypt in Rome May 10-20, 2010, and Oases of Egypt Oct 29 - Nov 15, 2010. Plus Bob Brier heads to Sudan in March of 2011. Be sure and read what former travelers have to say about Bob’s trips and register soon! With this newsletter we begin a new series written by Heather Stoeckley and Sara Barbieri, two members of the Far Horizons team who travel several times each year with our groups as tour manager. -

Sundowners Overland - Gobi Desert Explorer Page 1 of 6 Itinerary

Journey Itinerary Gobi Desert Explorer Days Westbound, Eastbound Countries Distance Activity level 16 Ulaanbaatar to Ulaanbaatar Mongolia 1,750 km Discover the very best of Mongolia, from the bustling capital Ulaanbaatar we journey across the steppe to Kharkhorin. We will encounter ancient Buddhist monasteries and the remarkable diversity of the Gobi Desert; sacred mountains, dinosaur ‘cemeteries’, flaming cliffs, singing sand dunes and spectacular canyons. Sundowners Overland - Gobi Desert Explorer Page 1 of 6 Itinerary Day 1: Ulaanbaatar Mongolia is the world’s most sparsely populated country with just 3 million people inhabiting the 1.5 million square kilometres of pristine desert, steppe and mountain. Almost half the population lives in its frenetic capital Ulaanbaatar where we will start our journey. Join your Tour Leader and fellow travellers on Day 1 at 5:00pm for your Welcome Meeting as detailed on your joining instructions. Meals - Day 1 – Dinner Day 2: To Bayangobi via Khustai National Park Beyond the city one million Mongolian’s still live a traditional nomadic or semi nomadic life and the horse is central to their existence. We visit the Gandan Monastery, with its huge gold Buddha, the spiritual home of the Mongolian people, before traveling to the Khustai National Park where wild horses, known as Tahki or Przewalski horses are bred and reintroduced to the wild. Once close to extinction, Takhi are the world’s only true wild horse. Mongolia is a country with such diverse landscapes and today we continue our way across the steppe to experience the uniqueness of the Bayangobi. Here we have the opportunity to hike in the stunning sand dunes that stretch over a distance of 80kms. -

An Old Turkic Statue from Borili, Ulytau Hills, Central Kazakhstan: Issues in Interpretation

THE METAL AGES AND MEDIEVAL PERIOD DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2018.46.1.059-065 L.N. Ermolenko1, A.I. Soloviev2, and Zh.K. Kurmankulov3 1Kemerovo State University, Krasnaya 6, Kemerovo, 650043, Russia E-mail: [email protected] 2Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography, Siberian Branch, Russian Academy of Sciences, Pr. Akademika Lavrentieva 17, Novosibirsk, 630090, Russia E-mail: [email protected] 3A.K. Margulan Institute of Archaeology, Committee of Science of the Ministry of Education and Science of the Republic of Kazakhstan, Pr. Dostyk 44, Almaty, 050010, Republic of Kazakhstan E-mail: [email protected] An Old Turkic Statue from Borili, Ulytau Hills, Central Kazakhstan: Issues in Interpretation We describe an unusual Old Turkic statue from Borili (Ulytau, Central Kazakhstan), distinguished by a peculiar position of the hands and holding an unusual object––a battle axe instead of a vessel. Stylistic features and possible prototypes among actual battle axes suggest that the statue dates to the 7th to early 8th centuries AD. The composition attests to the sculptor’s familiarity with Sogdian/Iranian art and with that of China. Several interpretations of the statue are possible. The standard version regarding Old Turkic statues erected near stone enclosures is that they represent divine chiefs––patrons of a specifi c group of the population. Certain details carved on the statue indicate an early origin of the image. It is also possible that such statues are semantically similar to those of guardians placed along the “path of the spirits” near tombs of members of the Chinese royal elite. Keywords: Old Turks, statues, Central Kazakhstan, Sogdian art, China, “path of the spirits”, bladed weapons. -

Mongolian Vision Tours

Mongolian Vision Tours FROM DESERT TO STEPPE Nomadic Mongolia waits for you in this tour in the heart of the nomadic life. From family to family, you will start your horse trek tour by the green Orkhon Valley, before going deeper in the remote area of Naiman Nuur. Then you'll go towards South, where the track disappears to give place to a legendary spot: the Gobi Desert, and the arid majesty of its lunar landscapes, with its towering rocky formations, frozen canyon and sand dunes. Day1. The granite formations of Baga Gazriin Chuluu Ulan Bator – Baga Gazriin Chuluu 250km Visit of Mountains Baga Gazriin Chuluu, where we'll observe stunning granite rock formations eroded by the violent elements of this area. In the 19th century, two respected lamas lived here, and we still can see their inscriptions in the rock. According to the legend, Genghis Khan to is supposed to have lived in this wonderful area where it's pleasant to walk. Stay overnight: Nomadic Family’s ger or tourist ger camp Day2. The great white stupa in the desert Baga Gazar Chuluu – white stupa 220km We travel in one of the emptiest areas of Mongolia. Between rock desert and semi-arid steppes, we reach the white stupa, Tsagaan Suvarga. For centuries, this 30-metre (98,43 feet) high, abrupt, stupa- shaped mountain, is honored by the Mongolians. The traveler will be surprised by the sumptuous lunar landscapes that evoke the end of the world, and by the many fossils. This area was totally covered by the sea a few million years ago. -

Review the Legacy of Nomadic Empires in Steppe Landscapes Of

ISSN 10193316, Herald of the Russian Academy of Sciences, 2009, Vol. 79, No. 5, pp. 473–479. © Pleiades Publishing, Ltd., 2009. Original Russian Text © A.A. Chibilev, S.V. Bogdanov, 2009, published in Vestnik Rossiiskoi Akademii Nauk, 2009, Vol. 79, No. 9, pp. 823–830. Review Information about the impact of nomadic peoples on the landscapes of the steppe zone of northern Eurasia in the 18th–19th centuries is generalized against a wide historical–geographical background, and the objec tives of a new scientific discipline, historical steppe studies, are substantiated. DOI: 10.1134/S1019331609050104 The Legacy of Nomadic Empires in Steppe Landscapes of Northern Eurasia A. A. Chibilev and S. V. Bogdanov* The steppe landscape zone covering more than settlements with groundbased or earthsheltered 8000 km from east to west has played an important role homes were situated close to fishing areas, watering in the history of Russia and, ultimately, the Old World places, and migration paths of wild ungulates. Steppe for many centuries. The ethnogenesis of many peoples bioresources were used extremely selectively. of northern Eurasia is associated with the historical– Nomadic peoples affected the steppe everywhere. The geographical space of the steppes. The continent’s nomadic, as opposed to semisedentary, lifestyle steppe and forest–steppe vistas became the cradle of implies a higher development of the territory. The nomadic cattle breeding in the early Bronze Age (from zone of economic use includes the whole nomadic the 5th through the early 2nd millennium B.C.). By area. Owing to this, nomads had an original classifica the 4th millennium B.C., horses and cattle were pre tion of its parts with regard to their suitability for set dominantly bred in northern Eurasia. -

Unit Plan – Silk Road Encounters

Unit Plan – Silk Road Encounters: Real and/or Imagined? Prepared for the Central Asia in World History NEH Summer Institute The Ohio State University, July 11-29, 2016 By Kitty Lam, History Faculty, Illinois Mathematics and Science Academy, Aurora, IL [email protected] Grade Level – 9-12 Subject/Relevant Topics – World History; trade, migration, nomadism, Xiongnu, Turks, Mongols Unit length – 4-8 weeks This unit plan outlines my approach to world history with a thematic focus on the movement of people, goods and ideas. The Silk Road serves a metaphor for one of the oldest and most significant networks for long distance east-west exchange, and offers ample opportunity for students to conceptualize movement in a world historical context. This unit provides a framework for students to consider the different kinds of people who facilitated cross-cultural exchange of goods and ideas and the multiple factors that shaped human mobility. This broad unit is divided into two parts: Part A emphasizes the significance of nomadic peoples in shaping Eurasian exchanges, and Part B focuses on the relationship between religion and trade. At the end of the unit, students will evaluate the use of the term “Silk Road” to describe this trade network. Contents Part A – Huns*, Turks, and Mongols, Oh My! (Overview) -------------------------------------------------- 2 Introductory Module ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 3 Module 1 – Let’s Get Down to Business to Defeat the Xiongnu ---------------------------------- -

I Am a Linguist Therefore I Am Kalmyk Reclaiming My Ethnic Identity

I am a linguist therefore I am Kalmyk Reclaiming my ethnic identity Elena Indjieva March 13, 2009 Linguistics Department University of Hawai‘i at Manoa Focus Reclaiming my ethnic identity The value of the linguistic heritage Oirat is a Western Mongolian language spoken in China, Russia, and Mongolia In Russia it’s called Kalmyk [xal’mg] In China and Mongolia it’s Oirat [oerd] Oirat = Kalmyk 400 years between Oirats in Russia and Oirats in China Causes of Kalmyk language and culture loss Soviet policies • Fight with illiteracy (early 20s) • Introduction of the Cyrillic alphabet (1924) (Losing touch with the written heritage) • Eradication of the religion (killing of about 2000 Buddhist monks) • Deportation to Siberia as a major blow (13 years of humiliation) • Decidedly assimilationist policies (Drastic cuts in native language education (1960-70s) the last Kalmyk national school was closed in 1963) In 1980s about 98% of Kalmyk pupils entering school at the age of seven don't speak their mother tongue. CPR for the Kalmyk language Revitalization policies • Russian and Kalmyk languages are declared the state languages of the Republic of Kalmykia (1991) • The Concept of the National System of Education (1993) • National schools are opened again (30 years later) • New Terminology Committee As a result we have it all • Oriental architecture, sculpture • Billboards with scenes from the traditional epic • Signs written in the old Kalmyk vertical writing • CDs with national folklore songs • National dance ensemble • Traditional celebrations • -

On the Features of the Sedentary Constructions of Zunghars and Defensive Sistem

JOURNAL OF CRITICAL REVIEWS ISSN- 2394-5125 VOL 7, ISSUE 08, 2020 ON THE FEATURES OF THE SEDENTARY CONSTRUCTIONS OF ZUNGHARS AND DEFENSIVE SISTEM Dordzhi G. Kukeev1, Nina V. Shorvaeva2 1 Federal State Budgetary Educational Institution of Higher Education Kalmyk State university named after B.B. Gorodovikov, 358000, Pushkin Street, 11. Elista, Russia. 2Federal State Budgetary Educational Institution of Higher Education Kalmyk State university named after B.B. Gorodovikov, 358000, Pushkin Street, 11. Elista, Russia. E-mail:1 [email protected] Received: 11.03.2020 Revised: 12.04.2020 Accepted: 28.05.2020 ABSTRACT: Because of the importance of studying the history of relations of the Qing dynasty with the peoples of Central Asia in the 18th and 19th centuries, and the existence of the phenomenon referred to as the “Zunghar heritage”, it is appropriate to study its background in the defensive systems of Zunghar and Qing Empires in Central Asia. There is a recent tendency to mention the so-called “Zunghar legacy” in the works of modern historiography on the history of Central Eurasia. It means like as a combination of political traditions, administrative and economic activities and methods of contacts, which were adopted by the Qing authorities from the Oirats. The researchers, actively using Manchu sources, explain the nature of the using of this “legacy” by the Qing through the model of “North Asian policy”, the “Qing world order” or the “Central Eurasian tradition”. In this regard and according to the logic, a comparative method and an attempt to make clear the genesis of a phenomenon, which had related to the Qing-Oirat relations before the contact of the Qing with Central Asia, west of Xinjiang, should also cause some interest in Qing and Central Asian studies, especially in the area of sedentary constructions of Zunghars and defensive system, named “Karul” or “Karun”.