Geoffroy De Charny's Second Funeral Part I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Late-Medieval France

Late-Medieval France: A Nation under Construction A study of French national identity formation and the emerging of national consciousness, before and during the Hundred Years War, 1200-1453 Job van den Broek MA History of Politics and Society Dr. Christian Wicke Utrecht University 22 June 2020 Word count: 13.738 2 “Ah! Doulce France! Amie, je te lairay briefment”1 -Attributed to Bertrand du Guesclin, 1380 Images on front page: The kings of France, England, Navarre and the duke of Burgundy (as Count of Charolais), as depicted in the Grand Armorial Équestre de la Toison d’Or, 1435- 1438. 1 Cuvelier in Charrière, volume 2, pp 320. ”Ah, sweet France, my friend, I must leave you very soon.” Translation my own. 2 3 Abstract Whether nations and nationalism are ancient or more recent phenomena is one of the core debates of nationalism studies. Since the 1980’s, modernism, claiming that nations are distinctively modern, has been the dominant view. In this thesis, I challenge this dominant view by doing an extensive case-study into late-medieval France, applying modernist definitions and approaches to a pre-modern era. France has by many regarded as one of the ‘founding fathers’ of the club of nations and has a long and rich history and thus makes a case-study for such an endeavour. I start with mapping the field of French identity formation in the thirteenth century, which mostly revolved around the royal court in Paris. With that established, I move on to the Hundred Years War and the consequences of this war for French identity. -

Competing Images of Pedro I: López De Ayala and the Formation of Historical Memory

Competing Images Of Pedro I: López De Ayala And The Formation Of Historical Memory Bretton Rodriguez La corónica: A Journal of Medieval Hispanic Languages, Literatures, and Cultures, Volume 45, Number 2, Spring 2017, pp. 79-108 (Article) Published by La corónica: A Journal of Medieval Hispanic Languages, Literatures, and Cultures DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/cor.2017.0005 For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/669500 [ Access provided at 2 Oct 2021 01:14 GMT with no institutional affiliation ] COMPETING IMAGES OF PEDRO I: LÓPEZ DE AYALA AND THE FORMATION OF HISTORICAL MEMORY. Bretton Rodriguez UNIVERSITY OF NEVADA, RENO Abstract: This article explores how Pero López de Ayala crafted the historical memory of Pedro I. By depicting him as a cruel tyrant, Ayala justified his deposition and murder at the hands of his half-brother, Enrique II, and he shaped the way that Pedro would be remembered by future generations. In the years following Pedro’s death, numerous authors composed narratives that promoted competing images of the deposed king. These narratives were influenced by the continuing conflict between Pedro’s descendants and Enrique’s new dynasty, and they frequently supported specific political positions. By examining Ayala’s depiction of four key moments from Pedro’s reign against those of his contemporaries, this article places his narrative within its larger historical and literary context, highlights some of the ways that political concerns shaped his account, and also provides insight into how he was able to successfully promote his image of the former king. LA CORÓNICA 45.2 SPRING 2017 79-108 RODRIGUEZ LA CORÓNICA 45.2, 2017 The tumultuous life and violent death of Pedro I of Castile (r. -

Liste Des Communes Situées Sur Une Zone À Enjeu Eau Potable

Liste des communes situées sur une zone à enjeu eau potable Enjeu eau Nom commune Code INSEE potable ABANCOURT 59001 Oui ABBEVILLE 80001 Oui ABLAINCOURT-PRESSOIR 80002 Non ABLAIN-SAINT-NAZAIRE 62001 Oui ABLAINZEVELLE 62002 Non ABSCON 59002 Oui ACHEUX-EN-AMIENOIS 80003 Non ACHEUX-EN-VIMEU 80004 Non ACHEVILLE 62003 Oui ACHICOURT 62004 Oui ACHIET-LE-GRAND 62005 Non ACHIET-LE-PETIT 62006 Non ACQ 62007 Non ACQUIN-WESTBECOURT 62008 Oui ADINFER 62009 Oui AFFRINGUES 62010 Non AGENVILLE 80005 Non AGENVILLERS 80006 Non AGNEZ-LES-DUISANS 62011 Oui AGNIERES 62012 Non AGNY 62013 Oui AIBES 59003 Oui AILLY-LE-HAUT-CLOCHER 80009 Oui AILLY-SUR-NOYE 80010 Non AILLY-SUR-SOMME 80011 Oui AIRAINES 80013 Non AIRE-SUR-LA-LYS 62014 Oui AIRON-NOTRE-DAME 62015 Oui AIRON-SAINT-VAAST 62016 Oui AISONVILLE-ET-BERNOVILLE 02006 Non AIX 59004 Non AIX-EN-ERGNY 62017 Non AIX-EN-ISSART 62018 Non AIX-NOULETTE 62019 Oui AIZECOURT-LE-BAS 80014 Non AIZECOURT-LE-HAUT 80015 Non ALBERT 80016 Non ALEMBON 62020 Oui ALETTE 62021 Non ALINCTHUN 62022 Oui ALLAINES 80017 Non ALLENAY 80018 Non Page 1/59 Liste des communes situées sur une zone à enjeu eau potable Enjeu eau Nom commune Code INSEE potable ALLENNES-LES-MARAIS 59005 Oui ALLERY 80019 Non ALLONVILLE 80020 Non ALLOUAGNE 62023 Oui ALQUINES 62024 Non AMBLETEUSE 62025 Oui AMBRICOURT 62026 Non AMBRINES 62027 Non AMES 62028 Oui AMETTES 62029 Non AMFROIPRET 59006 Non AMIENS 80021 Oui AMPLIER 62030 Oui AMY 60011 Oui ANDAINVILLE 80022 Non ANDECHY 80023 Oui ANDRES 62031 Oui ANGRES 62032 Oui ANHIERS 59007 Non ANICHE 59008 Oui ANNAY 62033 -

Docob Site Natura 2000 Fr3100498.Pdf

Site NPC 025 ‘’Forêt de Tournehem et pelouses de la cuesta du pays de Licques’’. FR3100498 DOCUMENT D’OBJECTIFS Site NPC 025 ‘’Forêt de Tournehem et pelouses de la cuesta du pays de Licques’’. FR3100498 DOCUMENT D’OBJECTIFS Rédacteur Théophile DETAILLEUR (Parc naturel régional des Caps et Marais d’Opale) Etudes écologiques Biodiversita – Vincent Lejeune Office National des forêts- Bruno Dermaux Coordination Mammalogique du Nord de la France (CMNF) – Simon Dutilleul Etudes socio-économiques Chambre départementale d’agriculture du Pas-de-Calais – Thomas Froidure Office National des forêts- Bruno Dermaux Fédération départementale des chasseurs du Pas-de-Calais (FDC62) – Anais Caron Benjamin Bigot Cartographie Théophile Détailleur (Parc naturel régional des Caps et Marais d’Opale) Crédit photographique page de couverture (PNR CMO et CRPF photo Hêtraie). Document d’objectifs du site Natura 2000 ‘’Forêt de Tournehem et pelouses de la cuesta de Licques 2 PREAMBULE : PRESENTATION GENERALE DE NATURA 2000 A. Natura 2000 : le réseau des sites européens les plus prestigieux B. Qu’est ce qu’un document d’objectifs ? C. La désignation de la forêt de Tournehem et des pelouses de la cuesta du pays de Licques au sein du réseau Natura 2000. D. La fiche d’identité du site NPC025 E. Description synthétique du site Natura 2000 PARTIE I : PRESENTATION GENERALE DU SITE 18 I.1- Caractéristiques administratives et géographiques 19 I.1.1- Situation administrative 19 I.1.2- Périmètre du site 19 I.1.3- Description générale du site 20 I.2- Paysages 22 I.2.1- Unités -

Flags and Banners

Flags and Banners A Wikipedia Compilation by Michael A. Linton Contents 1 Flag 1 1.1 History ................................................. 2 1.2 National flags ............................................. 4 1.2.1 Civil flags ........................................... 8 1.2.2 War flags ........................................... 8 1.2.3 International flags ....................................... 8 1.3 At sea ................................................. 8 1.4 Shapes and designs .......................................... 9 1.4.1 Vertical flags ......................................... 12 1.5 Religious flags ............................................. 13 1.6 Linguistic flags ............................................. 13 1.7 In sports ................................................ 16 1.8 Diplomatic flags ............................................ 18 1.9 In politics ............................................... 18 1.10 Vehicle flags .............................................. 18 1.11 Swimming flags ............................................ 19 1.12 Railway flags .............................................. 20 1.13 Flagpoles ............................................... 21 1.13.1 Record heights ........................................ 21 1.13.2 Design ............................................. 21 1.14 Hoisting the flag ............................................ 21 1.15 Flags and communication ....................................... 21 1.16 Flapping ................................................ 23 1.17 See also ............................................... -

A Knights Own Book of Chivalry: Geoffroi De Charny Free

FREE A KNIGHTS OWN BOOK OF CHIVALRY: GEOFFROI DE CHARNY PDF Geoffroi de Charny,Richard W. Kaeuper,Elspeth Kennedy | 128 pages | 12 May 2005 | University of Pennsylvania Press | 9780812219098 | English | Pennsylvania, United States Geoffroi de Charny - Wikipedia Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to read. Want to Read saving…. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. Other editions. Enlarge cover. Error rating book. Refresh and try again. Open Preview See a Problem? Details if other :. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Return to Book Page. Richard W. Kaeuper Introduction. Elspeth Kennedy Translator. On the great influence of a valiant lord: "The companions, who see that good warriors are honored by the great lords for their prowess, become more determined to attain this level of prowess. Read how an aspiring knight of the fourteenth century would conduct himself and learn what he would have needed to know when traveling, fighting, appearing in court, and engaging fellow knights. This is the most authentic and complete manual on the day-to-day life of the knight that has survived the centuries, and this edition contains a specially commissioned introduction from historian Richard W. Kaeuper that gives the history of both the book and its author, who, among his other achievements, was the original owner of the Shroud of Turin. Get A Copy. Paperbackpages. More Details Original Title. Other Editions 3. Friend Reviews. To see what your friends thought of this book, please sign up. Lists with This Book. Community Reviews. Showing Average rating 4. Rating details. More filters. Sort order. -

The Downfall of Chivalry

Bucknell University Bucknell Digital Commons Honors Theses Student Theses Spring 2019 The oD wnfall of Chivalry: Tudor Disregard for Medieval Courtly Literature Jessica G. Downie Bucknell University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bucknell.edu/honors_theses Part of the European History Commons, and the Medieval History Commons Recommended Citation Downie, Jessica G., "The oD wnfall of Chivalry: Tudor Disregard for Medieval Courtly Literature" (2019). Honors Theses. 478. https://digitalcommons.bucknell.edu/honors_theses/478 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses at Bucknell Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Bucknell Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. iii Acknowledgments I would first like to thank my thesis advisor, Professor Jay Goodale, for guiding me through this process. You have challenged me in many ways to become a better historian and writer, and you have always been one of my biggest fans at Bucknell. Your continuous encouragement, support, and guidance have influenced me to become the student I am today. Thank you for making me love history even more and for sharing a similar taste in music. I promise that one day I will understand how to use a semi-colon properly. Thank you to my family for always supporting me with whatever I choose to do. Without you, I would not have had the courage to pursue my interests and take on the task of writing this thesis. Thank you for your endless love and support and for never allowing me to give up. -

Les Monts D'audrehem (Identifiant National : 310013682)

Date d'édition : 05/07/2018 https://inpn.mnhn.fr/zone/znieff/310013682 Les Monts d'Audrehem (Identifiant national : 310013682) (ZNIEFF Continentale de type 1) (Identifiant régional : 00330007) La citation de référence de cette fiche doit se faire comme suite : CBNBl, GON, CSN NPDC, DREAL NPDC , .- 310013682, Les Monts d'Audrehem. - INPN, SPN-MNHN Paris, 11P. https://inpn.mnhn.fr/zone/znieff/310013682.pdf Région en charge de la zone : Nord-Pas-de-Calais Rédacteur(s) :CBNBl, GON, CSN NPDC, DREAL NPDC Centroïde calculé : 576144°-2642832° Dates de validation régionale et nationale Date de premier avis CSRPN : 12/10/2010 Date actuelle d'avis CSRPN : 12/10/2010 Date de première diffusion INPN : 01/01/1900 Date de dernière diffusion INPN : 04/02/2015 1. DESCRIPTION ............................................................................................................................... 2 2. CRITERES D'INTERET DE LA ZONE ........................................................................................... 3 3. CRITERES DE DELIMITATION DE LA ZONE .............................................................................. 4 4. FACTEUR INFLUENCANT L'EVOLUTION DE LA ZONE ............................................................. 4 5. BILAN DES CONNAISSANCES - EFFORTS DES PROSPECTIONS ........................................... 5 6. HABITATS ...................................................................................................................................... 5 7. ESPECES ...................................................................................................................................... -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G. Phd, Mphil, Dclinpsychol) at the University of Edinburgh

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: • This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. • A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. • This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. • The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. • When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Wearing Identity: Colour and Costume in Meliador and Sir Gawain and the Green Knight Elysse Taillon Meredith Ph.D. in Medieval Studies The University of Edinburgh 2012 The contents of this thesis are my own original work, research, and composition, and have not been submitted for any other degree or professional qualification. Elysse Taillon Meredith 23 May 2012 Abstract Worn items are a crucial part of non-verbal social interaction that simultaneously exhibits communal, cultural, and political structures and individual preferences. This thesis examines the role of fictional costume and colour in constructing identities within two fourteenth-century Arthurian verse narratives: Froissart’s Middle French Meliador and the anonymous Middle English Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. To emphasise the imaginative value of material cultures and discuss the potential reception of fictional objects, the argument draws on illuminations from nine manuscripts of prose Arthurian stories. -

The Battles of Crécy and Poitiers

Hexkit Strategy Game System The Battles of Crécy and Poitiers Christoph Nahr [email protected] Abstract This document describes two scenarios (with variants) based on the battles of Crécy and Poitiers during the Hundred Years War. The scenarios themselves ship with Hexkit, a construction kit for turn-based strategy games. The current versions of the Hexkit software packages and related documents are available at the Hexkit home page, http://www.kynosarges.de/Hexkit.html. Please consult the ReadMe file in- cluded with the binary package for system requirements and other information. Online Reading. When viewing this document in Adobe Reader, you should see a document navigation tree to the left. Click on the “Bookmarks” tab if the navigation tree is hidden. Click on any tree node to jump to the corresponding section. Moreover, all entries in the following table of contents, and all phrases shown in blue color, are clickable hyperlinks that will take you to the section or address they describe. Hexkit User’s Guide Revision History Revision 2.0, published on 27 September 2009 Enhanced to cover the initial release of the Poitiers scenario with Hexkit 4.2.0. Revision 1.0.4, published on 27 June 2009 Changed visual appearance of open terrain (again) in Hexkit 4.1.5. Revision 1.0.3, published on 24 December 2008 Changed visual appearance of sloping terrain in Hexkit 4.0.0. Revision 1.0.2, published on 10 June 2008 Added spontaneous rallying of routed units, introduced with Hexkit 3.7.2. Revision 1.0.1, published on 02 June 2008 Slight stylistic revision, coinciding with the release of Hexkit 3.7.1. -

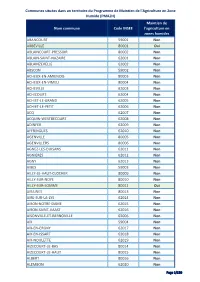

(PMAZH) Nom Commune Code INSEE

Communes situées dans un territoire du Programme de Maintien de l'Agriculture en Zone Humide (PMAZH) Maintien de Nom commune Code INSEE l'agriculture en zones humides ABANCOURT 59001 Non ABBEVILLE 80001 Oui ABLAINCOURT-PRESSOIR 80002 Non ABLAIN-SAINT-NAZAIRE 62001 Non ABLAINZEVELLE 62002 Non ABSCON 59002 Non ACHEUX-EN-AMIENOIS 80003 Non ACHEUX-EN-VIMEU 80004 Non ACHEVILLE 62003 Non ACHICOURT 62004 Non ACHIET-LE-GRAND 62005 Non ACHIET-LE-PETIT 62006 Non ACQ 62007 Non ACQUIN-WESTBECOURT 62008 Non ADINFER 62009 Non AFFRINGUES 62010 Non AGENVILLE 80005 Non AGENVILLERS 80006 Non AGNEZ-LES-DUISANS 62011 Non AGNIERES 62012 Non AGNY 62013 Non AIBES 59003 Non AILLY-LE-HAUT-CLOCHER 80009 Non AILLY-SUR-NOYE 80010 Non AILLY-SUR-SOMME 80011 Oui AIRAINES 80013 Non AIRE-SUR-LA-LYS 62014 Non AIRON-NOTRE-DAME 62015 Non AIRON-SAINT-VAAST 62016 Non AISONVILLE-ET-BERNOVILLE 02006 Non AIX 59004 Non AIX-EN-ERGNY 62017 Non AIX-EN-ISSART 62018 Non AIX-NOULETTE 62019 Non AIZECOURT-LE-BAS 80014 Non AIZECOURT-LE-HAUT 80015 Non ALBERT 80016 Non ALEMBON 62020 Non Page 1/130 Communes situées dans un territoire du Programme de Maintien de l'Agriculture en Zone Humide (PMAZH) Maintien de Nom commune Code INSEE l'agriculture en zones humides ALETTE 62021 Non ALINCTHUN 62022 Non ALLAINES 80017 Non ALLENAY 80018 Non ALLENNES-LES-MARAIS 59005 Non ALLERY 80019 Non ALLONVILLE 80020 Non ALLOUAGNE 62023 Non ALQUINES 62024 Non AMBLETEUSE 62025 Oui AMBRICOURT 62026 Non AMBRINES 62027 Non AMES 62028 Non AMETTES 62029 Non AMFROIPRET 59006 Non AMIENS 80021 Oui AMPLIER 62030 Non AMY -

Wavrans Sur L'aa

Comité d'Histoire du Haut Pays Relevés de mariage Wavrans sur l'Aa avec indication des contrats de mariage se trouvant à la bibliothèque de Saint Omer 1693 - 1913 mise à jour le Jean Luc CHEVALIER d'après un gedcom de Gérard DEMAGNY réalisé à partir des relevés de Mme ANNE et quelques compléments provenant d'autres relevés BMS et des contrats de mariage date conjoints date de naissance lieu de naissance père mère 25.7.1825 ALET Jph Louis 27.1.1781 Thiembronne ALET Jacques CAUX Marie Jeanne FASQUELLE Marie Philippine Jph 26.1.1778 Wavrans sur L'Aa FASQUELLE Gérard DUCROCQ Marie Marguerite Jph 11.3.1891 ALLOUCHERY Artur Jph Faustin 15.2.1869 Wavrans sur L'Aa ALLOUCHERY Marc Jph DUBOIS Adéle Hortense DAVROULT Marie Louise Adèle 17.3.1871 Wavrans sur L'Aa DAVROULT Gustave Jph BARROIS Adele Jph 4013 ALLOUCHERY Casimir Jph 24.11.1884 Cléty ALLOUCHERY Auguste Jph BRICHE Benjamine Léonie DEMBLOCQUE Jeanne Marie Virginie 24.11.1890 Wavrans sur L'Aa DEMBLOCQUE Charles COIGNON Émérance 7.10.1866 ALLOUCHERY Charles Louis 17.8.1839 Wavrans sur L'Aa ALLOUCHERY Jean Marie Célestin BERNARD Marie Augustine Jph WIMILLE Joséphine Eugènie 4.4.1840 Coulomby WIMILLE Jean Marie François LIARD Feumie Eugènie 7.2.1872 ALLOUCHERY Edouard Cesar 20.9.1841 Wavrans sur L'Aa ALLOUCHERY Jean Marie Célestin BERNARD Marie Augustine Jph GARÇON Léocadie Zélie Marie 6.9.1851 Esquerdes GARÇON Désiré GUILBERT Marie Catherine 26.1.1889 ALLOUCHERY Emile Jph Edouard 7.1.1867 Wavrans sur L'Aa ALLOUCHERY Charles Louis WIMILLE Joséphine Eugènie PORTENART Marie Apolline 6.2.1869 Delettes