Chapter Three Art and Identity: a Specific Reading of the Visual Arts Practices of Assam from 1970 Onwards

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Debojit Saha

DEBOJIT SAHA Debojit hails from a quaint little town called Silchar, which is nestled in the picturesque Barak valley in Assam. His tryst with music is not limited to the last four years of fame and success that the Zee Saregamapa embraced him with, when he won the “Voice of India” title. Since childhood, he grew up amidst nature, feeling and appreciating the nuances of musical notes. He took up the job of a Civil engineer in PWD, Assam, in order to meet ends; while music was the only thing that kept running through his veins. His mother always desired to see him become a professional singer. These dreams shattered when Debojit lost his mother to an illness. His wife Bandana took over from there; encouraged him and gave him the impetus to chase those dreams. It was with her support, that he set out to pursue his dreams - and what followed one after the other was just inevitable! Debojit started out as a singer in All India Radio and the Doordarshan Kendra in Silchar. He also leveraged on several opportunities to sing in concerts around Assam and West Bengal. Finally, life brought him to a crossroad where he had to make his choice between his job and passion for music. He took the plunge to shift base to Mumbai along with Bandana and enrolled himself to learn Indian Classical music from the Maestro Pt Askaran Sharma. He got certified in Sangeet Visharad Part-I, which was one of the building blocks in his musical career. He won the “Mega- final Runner Up” position in a music contest called “GAZAL-e-SARA” on an E-TV’s Urdu Channel. -

Speech-Ridden Dipanwita Pal

A non-profit 501(c)(3) Tax Exempt Organization incorporated in the state of Connecticut Board Of Authority Priest Tarun Chowdhury, Samir Podder, Animesh Chandra and Satyabrata Sau, Suman De Sponsor Tarun Chowdhury, Nirupam Basu and Kaushik Mitra, Samir Podder, Sanchita Maitra, Madhurima De, Saborna Das Publicity: Tarun Chowdhury, Prabir Patra , Animesh Chandra, Satyabrata Sau, Arya Bhattacharya, Subhasish Ganguly Food: Nirupam Basu, Kaushik Mitra, Satyabrata Sau, Ranjit Basak, DhrubaJyoti Chatterjee, Soumitro Mukherjee, Suman De, Arindam Guha, Vivekbrata Basu, Arindam Chakraborty Puja: Sanchita Maitra, Mithu Saha, Joyeeta Basak, Debasish & Kaberi Das Advertisement: Kaushik Mitra, Samir Podder, Satyabrata Sau, Girija Bhunia, Soumitro Mukherjee, Animesh Chandra, Sanchita Maitra Artist: Subhasish Ganguly, Sanjit Sanyal, Nirupam Basu, Animesh Chandra Sound System Prabal Ghosh, Animesh Chandra and Sanjit Sanyal and Light: Decoration: Girija Bhunia, RajNarayan Basak, Abhijit Roy, Arindam Guha Vendor Tarun Chowdhury, Sanjit Sanyal, Prabir Patra, DhrubaJyoti Chatterjee, Samir Podder Management: Venue: Nirupam Basu, Tarun Chowdhury, Sanchita Maitra, Sanjit Sanyal Transportation Kaushik Mitra, Sanjit Sanyal, Raj Basak, Arindam Guha Logistics Priest Transport Sanjit Sanyal, Animesh Chandra, Satyabrata Sau, Samir Poddar Community Kaushik Mitra, Tarun Choudhury, Animesh Chandra, Nirupam Basu, Sanchita Maitra Program Executive Committee Animesh Chandra Kaushik Mitra Sanjit Sanyal RajNarayan Basak Nirupam Basu Soumitro Mukherjee Samir Podder Tarun Chowdhury Sanchita Maitra Souvenir Magazine editing, material acquisition, layout and design Animesh Chandra Message from NASKA Welcome to 2015 NASKA KaliPuja celebration! Over the past several years, NASKA has been laser focused both on connecting with our broader community in North America and continuing to pass on our rich heritage to our future generations. Today, with great pleasure we bring to you an evening of joyful and fulfilling festivities at Hamden Middle School, Connecticut. -

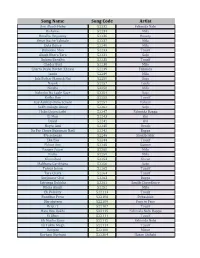

Song Name Song Code Artist

Song Name Song Code Artist Ami Akash Hobo 52232 Fahmida Nabi Bishshas 52234 Mila Bondhu Doyamoy 52236 Beauty Bristi Nache Taletale 52237 Mila Dola Dance 52240 Mila Bishonno Mon 52233 Tausif Akash Bhora Tara 52231 Saju Bolona Bondhu 52235 Tausif Chader Buri 52238 Mila Charta Deyal Hothat Kheyal 52239 Fahmida Jaadu 52249 Mila Jala Bojhar Manush Nai 52250 Saju Nayok 52257 Leela Nirobe 52258 Mila Kolonko Na Lagle Gaye 52254 Saju Kotha Dao 52255 Tausif Kay Aankay Onno Schobi 52251 Tahsan Sokhi Bologo Amay 52262 Saju Hobo Dujon Sathi 52247 Fahmida Bappa Ei Mon 52243 Oni Doyal 52241 Ovi Hoyto Ami 52248 Ornob Du Par Chuya Bohoman Nadi 52242 Bappa Eto sohosay 52246 Shakib Jakir Eka Eka 52244 Tausif Ekhon Ami 52245 Sumon Paaper Pujari 52260 Mila Nisha 52259 Mila Khunshuti 52253 Shuvo Malikana Garikhana 52256 Saju Tomar Jonno 52265 Tausif Tare Chara 52264 Tausif Surjosane Chol 52263 Bappa Satranga Dukkha 52261 Sanjib Chowdhury Khola Akash 52252 Mila Ek Polokey 522113 Tausif Bondhur Prem 522106 Debashish Dhrubotara 522109 Face to Face Bristi 2 522107 Tausif Hate Deo Rakhi 522115 Fahmida Nobi Bappa Ei Jibon 522111 Tausif Ek Mutho Gaan 522112 Fahmida Nobi Ek Tukro Megh 522114 Tausif Danpite 522108 Minar Kurbani Kurbani 522304 Hasan Shihabi Premchara Cholena Duniya 522342 Saju Rodela Dupur 522348 Tahsan Mithila Jeona Durey Chole 522280 Bappa Toni Khachar Bhitor Ochin Pakhi 522291 Labonno Kumari 522303 Shohor Bondi Nach mayuri nach re 522341 Labonno Tumi Amar 522381 Shahed Chandkumari 522385 Purno Soilo Soi 522391 Purno Itihas 71 522534 ROCK 404 Chandrabindu -

Perception Analysis of TV Reality Shows: Perspective of Viewers’ and Entertainment Industry Professionals

International Journal of Media, Journalism and Mass Communications (IJMJMC) Volume 7, Issue 2, 2021, PP 22-31 ISSN 2454-9479 https://doi.org/10.20431/2454-9479.0702003 www.arcjournals.org Perception Analysis of TV Reality Shows: Perspective of Viewers’ and Entertainment Industry Professionals. Souvik Das*, Dr. Partha Sarkar, Dr.S.M Alfarid Hussain Department of Mass Communication, Assam University, Silchar, Assam. *Corresponding Author: Souvik Das, Department of Mass Communication, Assam University, Silchar, Assam. Abstract: Television content is predominantly classified into fiction and non-fiction category which further diversifies in various subcategories. Reality shows are propositioned as entertainment content under non-fiction format in contrast to fictionalised events that are acted in. Road to stardom and affluence is made easier through participation in Reality TV Shows. Extensive audience reach through Television Rating Points(TRP) and support over various social media platforms is achieved through the manufacturing of controversies. Channels are making use of viewer’s emotions both in positive as well as negative ways. Many viewers are obscure about the intent of the show makers. The authenticity of Reality TV Shows as real or unreal has been under contention. Therefore, in the present study, an attempt has been made to understand how an audience perceives the programming tools used in Reality TV shows and how the TV industry professionals perceive the way Reality TV Shows function and delivers their content to the audiences at large. The study employed mixed-method research. Keywords: Societal Perception, Reality Shows, TRPs, Celebrities, Audience Research 1. INTRODUCTION “The world of reality has its limits; the world of imagination is boundless.” – Jean Jacques Rousseau When the famous 18th-century philosopher and writer Jean Jacques Rousseau quoted the lines he too emphasised on the aspects of what appears as reality may have its limitations while the imaginative world is more boundless in presenting them. -

INDIA -.:: GEOCITIES.Ws

1 INDIA RISES IN THE WEST A HISTORY REWRITTEN RANGANATHAN MAGADI 2006 2 INDIA RISES IN THE WEST Author Ranganathan Magadi Copyrighted ©2006 by Ranganathan Magadi Published by Ranganathan Magadi, Shobha Sreenath and Jamuna Mysore No part of this book can be copied or reproduced in any form or in any manner without a written permission from the author or the publishers. First printed and published in USA in 2006 E mail address: [email protected] Or [email protected] 3 Author’s note This book is not a discourse on any abstract ideology but an attempt to provide a layman’s knowledge of India and its people, past and present; to portray the strength, weakness, and follies of their leaders and to sketch the lives and achievements of great men who made India great in the fields of political progress, economic development, social transformation, industrialization, education, literature, sports and entertainment. The author has collected materials from various sources and presented them in such a way as to provide sufficient knowledge regarding the bane and boon of the country, the frailty and strength of its leaders and the myth and reality of its people. While the material is based on historical facts and figures, the author claims that the observations made and the conclusions drawn are his own. The author has no intention of hurting the sentiments of anyone or any group of people and the observations made and the inferences drawn are purely based on author’s evaluation of events, personalities and achievements. There is need to rewrite the History of India because no other history has been so distorted as the History of India.