Arxiv:1706.07447V1 [Astro-Ph.EP] 22 Jun 2017 Periods

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sirius Astronomer

September 2015 Free to members, subscriptions $12 for 12 issues Volume 42, Number 9 Jeff Horne created this image of the crater Copernicus on September 13, 2005 from his observing site in Irvine. September 19 is International Observe The Moon Night, so get out there and have a look at a source of light pollution we really don’t mind! OCA MEETING STAR PARTIES COMING UP The free and open club meeng will The Black Star Canyon site will open on The next session of the Beginners be held September 18 at 7:30 PM in September 5. The Anza site will be open on Class will be held at the Heritage Mu‐ the Irvine Lecture Hall of the Hashing‐ September 12. Members are encouraged to seum of Orange County at 3101 West er Science Center at Chapman Univer‐ check the website calendar for the latest Harvard Street in Santa Ana on Sep‐ sity in Orange. This month, JPL’s Dr. updates on star pares and other events. tember 4. The following class will be Dave Doody will discuss the Grand held October 2. Finale of the historic Cassini mission to Please check the website calendar for the Saturn in 2017! outreach events this month! Volunteers are GOTO SIG: TBA always welcome! Astro‐Imagers SIG: Sept. 8, Oct. 13 NEXT MEETINGS: October 9, Novem‐ Remote Telescopes: TBA You are also reminded to check the web ber 13 Astrophysics SIG: Sept. 11, Oct. 16 site frequently for updates to the calendar Dark Sky Group: TBA of events and other club news. -

Chaos in the Inert Oort Cloud

EPSC Abstracts Vol. 13, EPSC-DPS2019-1303-1, 2019 EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2019 c Author(s) 2019. CC Attribution 4.0 license. Chaos in the inert Oort cloud Melaine Saillenfest (1), Marc Fouchard (1), and Arika Higuchi (2) (1) IMCCE, Observatoire de Paris, France, (2) RISE Project Office/NAOJ, Mitaka, Tokyo, Japan e-mail: [email protected] µ 16 Abstract 2 εP − εG ÝÖ 14 2 We investigate the orbital dynamics of small bodies in aÙ 9 12 the intermediate regime between the Kuiper belt and − 10 the Oort cloud, i.e. where the planetary perturbations ´ 10 and the galactic tides have the same order of magni- 8 tude. We show that this region is far less inert than it could appear at first sight, despite very weak orbital 6 perturbations. Ô eÖØÙÖbaØiÓÒ 4 Øhe Óf 2 1. Introduction ×iÞe 0 0 500 1000 1500 2000 2500 3000 aÜi× ´aÙµ The orbits of distant trans-Neptunian objects are sub- ×eÑi¹Ña jÓÖ a ject to internal perturbations from the planets, and ex- ternal perturbations from the galactic tides. A distinc- Figure 1: Size of the small parameters appearing in tion is generally made between the Kuiper belt and the the Hamiltonian function (Eq. 1) with respect to the Oort cloud, which are thought to have been initially semi-major axis of the small body. The red curve rep- populated through distinct mechanisms (see e.g. the resents the planetary perturbations, and the blue curve recent review by [4]). However, there is no dynamical represents the galactic tides. boundary between the two populations, and numerical simulations show a continuous transfer of objects in 2. -

NOAO Hosts “Colors of Nature” Summer Academy

On the Cover The cover shows an 8 × 9 arcminutes image of a portion of the Milky Way galactic bulge, obtained as part of the Blanco DECam Bulge Survey (BDBS) using the Dark Energy Camera (DECam) on the CTIO Blanco 4-m telescope. In this image, red, green, and blue (RGB) pixels correspond to DECam’s Y, z and i filters, respectively. The inset image shows the 2 × 3 array of monitors at the “observer2” workstation in the Blanco control room. The six chips shown here represent only 10% of the camera’s field of view. For more information about the BDBS and their experiences observing with DECam, see the “The Blanco DECam Bulge Survey (BDBS)” article in the Science Highlights section of this Newsletter. (Image credit: Will Clarkson, University of Michigan-Dearborn; Kathy Vivas, NOAO; R. Michael Rich, UCLA; and the BDBS team.) NOAO Newsletter NATIONAL OPTICAL ASTRONOMY OBSERVATORY ISSUE 110 — SEPTEMBER 2014 Director’s Corner Under Construction: A Revised KPNO Program Emerges ................ 2 CTIO Instruments Available for 2015A ......................................... 18 Gemini Instruments Available for 2015A ..................................... 19 Science Highlights KPNO Instruments Available for 2015A........................................ 20 The Survey of the MAgellanic Stellar History (SMASH) ................... 3 AAT Instruments Available for 2015A .......................................... 21 Two’s Company in the Inner Oort Cloud ......................................... 5 CHARA Instruments Available for 2015 ....................................... -

CFAS Astropicture of the Month

1 What object has the furthest known orbit in our Solar System? In terms of how close it will ever get to the Sun, the new answer is 2012 VP113, an object currently over twice the distance of Pluto from the Sun. Pictured above is a series of discovery images taken with the Dark Energy Camera attached to the NOAO's Blanco 4-meter Telescope in Chile in 2012 and released last week. The distant object, seen moving on the lower right, is thought to be a dwarf planet like Pluto. Previously, the furthest known dwarf planet was Sedna, discovered in 2003. Given how little of the sky was searched, it is likely that as many as 1,000 more objects like 2012 VP113 exist in the outer Solar System. 2012 VP113 is currently near its closest approach to the Sun, in about 2,000 years it will be over five times further. Some scientists hypothesize that the reason why objects like Sedna and 2012 VP113 have their present orbits is because they were gravitationally scattered there by a much larger object -- possibly a very distant undiscovered planet. Orbital Data: JDAphelion 449 ± 14 AU (Q) Perihelion 80.5 ± 0.6 AU (q) Semi-major axis 264 ± 8.3 AU (a) Eccentricity 0.696 ± 0.011 Orbital period4313 ± 204 yr 2 Discovery images taken on November 5, 2012. A merger of three discovery images, the red, green and blue dots on the image represent 2012 VP113's location on each of the images, taken two hours apart from each other. 2012 VP113, also written 2012 VP113, is the detached object in the Solar System with the largest known perihelion (closest approach to the Sun) -

11000 Scientists Around the World Have the Final Say on What's a Planet

International Astronomical Union (IAU) members vote on a new planet definition during a meeting in Prague Aug. 24, 2006. The vote redefined Pluto as a dwarf planet. MICHAL CIZEK/AFP/GETTY IMAGES DEFINITION: PLANET 11,000 scientists around the world have the final say on what’s a planet — or not By Mary Helen Berg a planet is a planet or just an orbiting ice of planetary scientists, academics and ball. Right now, the worlds that make historians support research, confirm HE NUMBER OF PLANETS IN OUR the cut are Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, celestial discoveries, document and solar system is … well, it depends Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune. preserve data and even track potentially on who you ask. Pluto fans, sporting The IAU is “responsible for managing the dangerous asteroids. T-shirts that read “Never Forget,” astronomical world,” said Gareth Williams, Tstill say there are nine. Meanwhile, some associate director of the NASA-funded IAU PLUTO OUT astronomers say the tally should be 13. But Minor Planet Center (MPC). “They define Most of these working groups fly under the arbiter on all things astronomical, the everything that astronomers need to talk the radar. But in 2006, one committee International Astronomical Union (IAU), about objects in a consistent way. So, if I’m found itself under global scrutiny when, for recognizes only eight planets. talking about an object at a certain point the first time, the astronomy community As the world’s largest professional in the sky, some other astronomer knows demanded an official definition of “planet.” organization for astronomers, the IAU exactly what I am talking about.” The seven-member Planet Definition represents 11,000 scientists from 95 In other words, the IAU controls cosmic countries and has the final say on whether chaos on Earth. -

Observational Constraints on Planet Nine: Astrometry of Pluto and Other

Observational Constraints on Planet Nine : Astrometry of Pluto and Other Trans-Neptunian Objects Matthew J. Holman and Matthew J. Payne Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, 60 Garden St., MS 51, Cambridge, MA 02138, USA [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] ABSTRACT We use astrometry of Pluto and other TNOs to constrain the sky location, distance, and mass of the possible additional planet (Planet Nine ) hypothesized by Batygin and Brown (2016). We find that over broad regions of the sky the inclusion of a massive, distant planet degrades the fits to the observations. However, in other regions, the fits are significantly improved by the addition of such a planet. Our best fits suggest a planet that is either more massive or closer than argued for by Batygin and Brown (2016) based on the orbital distribution of distant trans-neptunian objects (or by Fienga et al. (2016) based on range measured to the Cassini spacecraft). The trend to favor larger and closer perturbing planets is driven by the residuals to the astrometry of Pluto, remeasured from photographic plates using modern stellar catalogs (Buie and Folkner 2015), which show a clear trend in declination, over the course of two decades, that drive a preference for large perturbations. Although this trend may be the result of systematic errors of unknown origin in the observations, a possible resolution is that the declination trend may be due to perturbations from a body, additional to Planet Nine , that is closer to Pluto, but less massive than, Planet Nine . Subject headings: astrometry; ephemerides; Pluto; Kuiper belt 1. -

If Kepler-186F

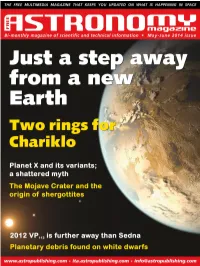

colophon EN:l'astrofilo 30/04/14 07:54 Page 2 A new astronomy magazine for you Dear Readers, Free Astronomy Magazine is pleased to welcome you. After more than 5 years of publications in Italian, the free multimedia magazine “l’Astrofilo” is now broadening its reach by publishing online the English version of the same. Our main objective is to deal in the most simple and detailed way with the latest discoveries made by professional astronomers. The choice of the topics covered takes into account the need to reach a wide as possible audience and avoid, therefore, subject matters or con- tents that are too technical. Any amateur astronomer with minimal scien- tific knowledge will be able to fully appreciate the articles published by Free Astronomy Magazine, but also those less-experienced beginners can surely find some interesting material to read. Accuracy of the scientific content, utmost graphic quality, ease of commu- nication and Readers’ satisfaction are the key concepts of our philosophy and publication activity. We would welcome your opinion about Free Astronomy Magazine. Have a nice read! Michele Ferrara Editor in chief editorial editorial kepler186 EN:l'Astrofilo 30/04/14 07:42 Page 4 4 EXOPLANETS JustJust aa stepstep away away frofromamanewnew EaEarthrth For the first time, the existence of a large planet like the Earth, with an orbit entirely inside the habitable zone of its star, has been confirmed. We do not know if it has an atmosphere and if its surface is favourable to life's flourishing, but its discovery is nonetheless an important landmark in the search for other Earths. -

A New High Perihelion Inner Oort Cloud Object

Draft version October 2, 2018 Typeset using LATEX preprint style in AASTeX62 A New High Perihelion Inner Oort Cloud Object Scott S. Sheppard,1 Chadwick A. Trujillo,2 David J. Tholen,3 and Nathan Kaib4 1Department of Terrestrial Magnetism, Carnegie Institution for Science, 5241 Broad Branch Rd. NW, Washington, DC 20015, USA, [email protected] 2Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff, AZ 86011, USA 3Institute for Astronomy, University of Hawai’i, Honolulu, HI 96822, USA 4HL Dodge Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Oklahoma, Norman, OK 73019, USA ABSTRACT Inner Oort Cloud objects have perihelia beyond the Kuiper Belt with semi-major axes less than a few thousand au. They are beyond the strong gravitational influences of the known planets yet are tightly bound to the Sun such that outside forces minimally affect them. Here we report the discovery of the third known Inner Oort Cloud object after Sedna and 2012 VP113, called 2015 TG387. 2015 TG387 has a perihelion of 65±1 au with a semi-major axis of 1190 ± 70 au. The longitude of perihelion angle for 2015 TG387 is between that of Sedna and 2012 VP113, and thus similar to the main group of clustered extreme trans-Neptunian objects (ETNOs), which may be shepherded into similar orbital angles by an unknown massive distant planet, called Planet X or Planet 9. 2015 TG387’s orbit is stable over the age of the solar system from the known planets and Galactic tide. When including simulated stellar encounters to our Sun over 4 Gyrs, 2015 TG387’s orbit is still mostly stable, but its dynamical evolution depends on the stellar encounter scenarios used. -

DISTANT Ekos

Issue No. 92 April 2014 ✤✜r s ✓✏ DISTANT EKO ❞✐ ✒✑ The Kuiper Belt Electronic Newsletter ✣✢ Edited by: Joel Wm. Parker [email protected] www.boulder.swri.edu/ekonews CONTENTS News & Announcements ................................. 2 Abstracts of 9 Accepted Papers ......................... 3 Titles of 3 Submitted Papers ........................... .10 Titles of 1 Other Paper of Interest ...................... 10 Conference Information .............................. 11 Newsletter Information .............................. 12 1 NEWS & ANNOUNCEMENTS There were 3 new TNO discoveries announced since the previous issue of Distant EKOs: 2011 HJ103, 2012 HZ84, 2012 XR157 and 10 new Centaur/SDO discoveries: 2011 HK103, 2012 VP113, 2013 FY27, 2013 FZ27, 2013 LU35, 2014 DT112, 2014 FW, 2014 FX43, 2014 GE45, 2014 HY123 Reclassified objects: 2010 GF65 (SDO → Centaur) 2012 GX17 (Centaur → SDO) 2014 FW (Centaur → SDO) 2013 FZ27 (SDO → TNO) Objects recently assigned numbers: 2011 WU92 = (389820) Objects recently assigned names: 2003 QW111 = Manwe Current number of TNOs: 1263 (including Pluto) Current number of Centaurs/SDOs: 393 Current number of Neptune Trojans: 9 Out of a total of 1665 objects: 644 have measurements from only one opposition 631 of those have had no measurements for more than a year 326 of those have arcs shorter than 10 days (for more details, see: http://www.boulder.swri.edu/ekonews/objects/recov_stats.jpg) 2 PAPERS ACCEPTED TO JOURNALS A Sedna-like Body with a Perihelion of 80 Astronomical Units C. Trujillo1 and S. Sheppard2 1 Gemini Observatory, 670 North A‘ohoku Place, Hilo, HI 96720, USA 2 Carnegie Institution for Science, 5241 Broad Branch Road NW, Washington, DC 20015, USA The observable Solar System can be divided into three distinct regions: the rocky terrestrial planets including the asteroids at 0.39 to 4.2 astronomical units (AU) from the Sun (where 1 AU is the mean distance between Earth and the Sun), the gas giant planets at 5 to 30 AU from the Sun, and the icy Kuiper belt objects at 30 to 50 AU from the Sun. -

Unseen Planet May Lurk Near Solar System's Edge

NEWS IN FOCUS PLANETARY SCIENCE Unseen planet may lurk near Solar System’s edge Gravitational signature hints at massive object that orbits the Sun every 20,000 years. BY ALEXANDRA WITZE FAR AFIELD The existence of an unseen 'Planet Nine' could explain the strange orbits of several 22 (2016) century after observatory founder Per- objects (whose orbits are shown in white) in the Kuiper belt beyond Neptune. 151, cival Lowell speculated that a ‘Planet X’ lurks at the fringes of the Solar System, 2010 GB Aastronomers say that they have the best evidence 174 Sedna yet for such a world. They call it Planet Nine. ASTRONOM. J. Orbital calculations suggest that Planet Nine, if it exists, is about ten times the mass of Earth and swings an elliptical path around the Sun once every 10,000–20,000 years. It would never get closer than about 200 times Sun Planet Nine the Earth–Sun distance, or 200 astronomical units (au). That range would put it far beyond AND M. E. BROWN K. BATYGIN 2012 VP113 Pluto, in the realm of icy bodies known as the 2004 VN Kuiper belt. 112 No one has seen Planet Nine, but researchers 2013 RF have inferred its existence from the way several 98 other Kuiper belt objects (KBOs) move. And 2007 TG422 given the history of speculation about distant 100 astronomical units planets (see ‘Solving for X’), Planet Nine may end up in the dustbin of good ideas gone wrong. “If I read this paper out of the blue, my first (K. Batygin and M. -

Chadwick A. Trujillo September 9, 2016

Chadwick A. Trujillo September 9, 2016 Contact Dept. of Physics and Astronomy phone: (928) 523-6007 Northern Arizona University email: [email protected] NAU Box 6010 Flagstaff, AZ 86011 Degrees 2000, Ph.D. Astronomy, University of Hawaii 1998, M.S. Astronomy, University of Hawaii 1995, B.S. Physics, minor Literature, Massachusetts Institute of Technology Employment 2016– , AssistantProfessor,Physics&AstronomyDept.,Northern Arizona Univ. 2013–2016, Head of Adaptive Optics / Telescope Dept., Gemini Observatory 2012–2016, Astronomer with Tenure, Gemini North Observatory 2006–2012, Assistant Astronomer, Gemini North Observatory 2003–2006, Science Fellow, Gemini North Observatory 2000–2003, Postdoctoral Scholar, California Institute of Technology 1996–2000, Research Assistant, University of Hawaii 1995–1996, Teaching Assistant, University of Hawaii Research Kuiper Belt, Inner Oort Cloud, the Outer Solar System, Planet Interests Formation, Titan, Active Asteroids Grant 2015–2017, Exploring the Inner Oort Cloud, NASA (NNX15AF44G $162,103) Principal 2012–2015, Beyond the Kuiper Belt Edge, NASA (NNX12AG26G $56,693) Investigator 2007–2012, Primordial Solar System Ices, NASA (NNX07AK96G $108,106) Astronomy 2010–2012, NOAO Telescope Allocation Committee, Solar System Service 2011, Thirty Meter Telescope NFIRAOS and IRIS Review Committees 2011, Hubble Space Telescope Cycle 19 Time Allocation Committee 2007, External Reviewer for Canada-France Hawaii and Subaru Telescopes 2006, External Reviewer for NASA Planetary Astronomy Grants 2005, Hubble Space Telescope Cycle 14 Time Allocation Committee 2003, NASA Planetary Astronomy Grant Allocation Committee Frequent Referee for Nature, ApJ, AJ, A&A, and Icarus Astronomy Optical Imaging: Observing 10 m Keck LRIS/B, ESI, DEIMOS 8.2 m Subaru Hyper Suprime-Cam Experience 8.1 m Gemini North & South GMOS 6.5 m Baade/Clay Tels., IMACS, Megacam 5.1 m Palomar JCAM and LFC 4.0 m KPNO Tel., 8k MOSAIC 1.1 4.0 m CTIO Tel. -

Nemesis, Tyche, Planet Nine Hypotheses. I. Can We Detect the Bodies Using Gravitational Lensing?

Publications of the Astronomical Society of Australia (PASA), Vol. 33, e033, 13 pages (2016). C Astronomical Society of Australia 2016; published by Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/pasa.2016.28 Nemesis, Tyche, Planet Nine Hypotheses. I. Can We Detect the Bodies Using Gravitational Lensing? J. P. Philippov1,3 and M. I. Chobanu2 1Samara State University, Academica Pavlova st 1, 443011, Samara, Russian Federation 2Samara International Aerospace Lyceum, Lukacheva st 45, 443086, Samara, Russian Federation 3Email: [email protected] (Received December 21, 2015; Accepted July 18, 2016) Abstract In this paper, the hypothesis of the existence of a massive dark body (Nemesis, Tyche, Planet Nine, or any other trans- Plutonian planet) at the Solar system periphery is analysed. Basic physical properties and orbital characteristics of such massive bodies are considered. The problem of the definition of a scattering angle of a photon in the gravitational field of a spherical lens is studied. It is shown that, the required value of the scattering angle can be measured for the cases of Nemesis and Tyche. The formation of gravitational lensing images is studied here for a point mass event. It is demonstrated that in most cases of the close rapprochement of a source and the lens (for Nemesis and Tyche), it is possible to resolve two images. The possibility of resolving these images is one of the main arguments favouring the gravitational lensing method as its efficiency in searching for dark massive objects at the edge of the Solar System is higher than the one corresponding to other methods such as stellar occultation.