The Wikipedian Discourse: a Foucauldian Archaeology of Power Relations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thesis (844.6Kb)

ABSTRACT You Should Have Expected Us – An Explanation of Anonymous Alex Gray Director: Linda Adams; PhD Anonymous is a decentralized activist collective that has evolved using the technology of the information age. This paper traces its origins as a way of contextualizing and better understanding its actions. The groups composition is examined using its self‐ascribed imagery to illustrate its’ unique culture and relational norms. Its structure and motivation are analyzed using the framework developed for social movements and terrorist networks. Finally a discussion of a splinter cell and official reaction delineate both strengths and weaknesses of the movement while suggesting its future development. The conclusion serves to expound on the ideal end for the online anonymous community as a new frontier in meritocratic activism. APPROVED BY DIRECTOR OF HONORS THESIS: ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ Dr. Linda Adams, Department of Political Science APPROVED BY THE HONORS PROGRAM: ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ Dr. Andrew Wisely, Director. DATE: ________________________ YOU SHOULD HAVE EXPECTED US AN EXPLANATION OF ANONYMOUS A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Baylor University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Honors Program By Alex Gray Waco, Texas May 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface iii Acknowledgements iv Dedication v CHAPTER ONE 1 Introduction CHAPTER TWO 4 The Story of Anonymous CHAPTER THREE 20 A Group with No Head and No Members CHAPTER FOUR 39 Activists or Terrorists CHAPTER FIVE 56 Distraction, Diversion, Division CHAPTER SIX 67 Conclusion Bibliography 71 ii PREFACE Writing a paper about a decentralized, online collective of similarly minded individuals presents a unique set of challenges. In spending so much time with this subject, it is my goal to be both intellectually honest and as thorough as I can be. -

The Coming Swarm.Indb

Sauter, Molly. "Which way to the #press channel? DDoS as media manipulation." The Coming Swarm: DDoS Actions, Hacktivism, and Civil Disobedience on the Internet. New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2014. 59–75. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 30 Sep. 2021. <http:// dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781628926705.0009>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 30 September 2021, 15:01 UTC. Copyright © Molly Sauter 2014. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. CHAPTER THREE Which way to the #press channel? DDoS as media manipulation The direct action DDoS provides participants with the theoretical structure and the tactical pathways to directly interact with systems of oppression. But, though disruption may be an effect of a DDoS action, the disruption itself is not always the greater goal of activists. Often, the disruption caused by the DDoS action is used as a tool to direct and manipulate media attention to issues the activists care about. We saw a related example of this in the Lufthansa/Deportation Class Action covered in the last chapter. The challenge for these types of actions, as with public, performative activism on the street, is getting the media to cover the issues that are driving the activist actions, and not merely the spectacle of the activism itself. In a campaign that primarily seeks to achieve change through the medium of popular attention, activists must enter into an often uneasy symbiotic relationship with the mass media industry. News coverage of an action may result in further coverage of an organization and a cause, which may, in turn, inform a public outcry or directly influence decision makers to initiate desired change. -

From Indymedia to Anonymous: Rethinking Action and Identity in Digital Cultures

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Middlesex University Research Repository From Indymedia to Anonymous: rethinking action and identity in digital cultures To cite this article: Kevin McDonald (2015): From Indymedia to Anonymous: rethinking action and identity in digital cultures, Information, Communication & Society, 18, 8, pp. 968-982, DOI: 10.1080/1369118X.2015.1039561 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2015.1039561 Kevin McDonald Middlesex University, London [email protected] Keywords: Anonymous, digital networking, social movements, transparency, information society, connective action, digital culture Beyond collective identity and networks The period following the mobilizations of 2011 – the Arab Spring, the Indignados movement in Spain, and Occupy Wall Street – has seen a new focus on the relationship between emerging practices of digital communications and emerging forms of collaborative action or movement. This has prompted new disciplinary encounters, as scholars working on social movements and collective action have begun to focus much more on the significance of communication processes. Within dominant approaches to social movement studies this represents a significant shift, to that the extent that the study of social movements has historically not attached a great significance to communication processes, which have been essentially understood within a ‘broadcasting’ paradigm, where collective actors ‘display’ their ‘worthiness, unity, numbers and commitment’ (Guini, McAdam & Tilly, 1999), principally by ‘occupy[ing] public space… to disrupt routines and gain media attention’ (Tilly & Tarrow, 2005 p. 20). This approach to social mobilization underlined the critical importance of ‘the shared definition of a group’ (Taylor & Whittier, 1992, p. -

The Megan Meier Myspace Suicide: a Case Study Exploring the Social

The Megan Meier MySpace Suicide: A case study exploring the social aspects of convergent media, citizen journalism, and online anonymity and credibility By: Jacqueline Vickery M.A. student, University of Texas at Austin, Dept. of Radio-TV-Film In his book, Convergence Culture, Henry Jenkins explores the changing relationship between media audiences, producers, and content, in what he refers to as convergence media. These changes are not only evidenced by changes in technology, but rather involve social changes as well. As historian Lisa Gitelman says, a medium is not merely a communication technology, but also a set of cultural and social practices enabled by the medium. The internet, as a medium, challenges traditional top-down approaches to traditional news gathering and reporting by affording opportunities for “average citizens” to participate in the journalistic process. Anyone with access to a computer and an internet connection can, in theory, participate in the journalistic process by gathering information, offering an alternative opinion, and engaging in dialog via message boards and blogs. However, a social concept entwined within this practice is the formation of disembodied communities and identities, in which participants can opt to remain anonymous. Such anonymity brings to the surface new questions of credibility, questions which seem to have few, if any, definitive answers as of yet. I will be examining the Megan Meier MySpace “hoax”1 as it has been dubbed by the media, as evidence of convergence media, and as an entry point into the unintended consequences of citizen journalism and online anonymity. As I write this, many questions and allegations are still circulating in regards to exactly what events transpired the month leading up to Megan’s suicide, who was involved, and what the legal repercussions (if 1 I am reluctant to use the word “hoax” to describe an event that resulted in the death of a 13 year-old girl, but since that is how the media most often refers to it, I will stick to that language. -

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT of ILLINOIS EASTERN DIVISION JOHN DOE, ) COMPLAINT ) Plaintiff, ) ) V

CaseCase 1:08-cv-01050 1:08-cv-01050 Document Document 28-2 30 Filed Filed 09/23/2008 09/08/2008 Page Page 1 1 of of 22 22 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ILLINOIS EASTERN DIVISION JOHN DOE, ) COMPLAINT ) Plaintiff, ) ) v. ) No. 08 C 1050 ) JASON FORTUNY, ) ) Defendant. ) DEMAND FOR JURY TRIAL AMENDED COMPLAINT NOW COMES the Plaintiff, JOHN DOE (“Plaintiff”), by and through his attorneys, Mudd Law Offices, and complains of the Defendant, JASON FORTUNY (“Mr. Fortuny”), a citizen and resident of the State of Washington, upon personal information as to his own activities and upon information and belief as to the activities of others and all other matters, and states as follows: NATURE OF ACTION 1. This is an action against Mr. Fortuny for violation of the Copyright Act, 17 U.S.C. § 501 et al.; Plaintiff’s right to privacy; and related claims arising from Mr. Fortuny’s unauthorized posting of Plaintiff’s photograph and personal information on the Internet. By this action, Plaintiff seeks, inter alia, compensatory damages, punitive damages, attorney’s fees and costs, and all other relief to which Plaintiff may be entitled as a matter of law and as deemed appropriate by this Court. PARTIES 2. JOHN DOE is a Washington citizen and resident of Seattle, Washington. CaseCase 1:08-cv-01050 1:08-cv-01050 Document Document 28-2 30 Filed Filed 09/23/2008 09/08/2008 Page Page 2 2 of of 22 22 3. Upon information and belief, JASON FORTUNY is a Washington citizen and resident of Kirkland, Washington. -

Hate and Violent Extremism from an Online Sub-Culture the Yom Kippur Terrorist Attack in Halle, Germany

Website: ohpi.org.au Facebook: facebook.com/onlinehate Twitter: twitter.com/OnlineHate E-mail: [email protected] Hate and Violent Extremism from an Online Sub-Culture The Yom Kippur Terrorist Attack in Halle, Germany DRAFT FOR CONSULTATION NOT FOR FURTHER RELEASE Copyright ©2019 Online Hate Prevention Institute Report: IR19-4 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Andre Oboler, William Allington and Patrick Scolyer-Gray Consultation Notes This version of the report is a draft for consultation with stakeholders prior to the release of the final report. All content, including findings and recommendations, are subject to further change as a result of the consultation process. • We invite stakeholders with direct knowledge of the facts described in this report to bring any errors or omissions to our attention. • We invite stakeholders and experts who disagree with a finding or recommendation to provide a brief counter argument. We will consider this and decide if the content ought to be revised. In case we decide not to revise our content, please indicate if you would be willing for your counter view to be included, and if so, what attribution you would like (your name, company / organisation name, anonymous etc) • We invite all stakeholders receiving this to provide a brief statement of support for this report. Such statements can: o Express support for specific aspects of the report o Welcome the contribution to the field without specifically endorsing the content o Raise other related ideas or recommendations Examples of such statements can be seen in our report on Islamophobia in 2013: https://ohpi.org.au/islamophobia-on-the-internet-the-growth-of-online-hate-targeting- muslims/ Feedback and statements are requested by December 12th. -

Life-Cycle of Internet Trolls

Terho Jussinoja LIFE-CYCLE OF INTERNET TROLLS UNIVERSITY OF JYVÄSKYLÄ FACULTY OF INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY 2018 ABSTRACT Jussinoja, Terho Life-cycle of Internet Trolls Jyväskylä: University of Jyväskylä, 2018, 107 p. Information Systems, Master’s Thesis This paper is a master’s thesis about internet trolls and trolling with the main goal of finding what is the life-cycle of internet trolls. In other words, how a person becomes a troll, how their trolling evolves, and how does trolling stop. Trolling definitions are also examined to see whether they are adequate. This thesis also covers the current state of research done on trolling, with the empha- sis on literature that is relevant to the life-cycle of a troll. The literature will also be evaluated against the results from this study. Past research on trolling is quite scarce when comparing to the multiple topics it holds, suggesting that the scientific understanding of internet trolls is still less than ideal. Most of the pre- vious studies have not been able to utilize trolls’ views, whereas this study only uses commentary from trolls. This study was conducted using a qualitative re- search method, thematic analysis, and used three different methods for data collection. Trolling has become more commonplace in recent years and it has been claimed to be a formidable problem for civil discourse on the internet and there- fore deserves better insight on the matter. Media accounts, literature, and public opinions rarely match when it comes to trolling. This shows that there is plenty of confusion and misunderstandings on the topic. By discovering the reasons why an individual decides to troll, and how they decide to stop, there can be better technological solutions developed that might discourage people to start trolling or encourage them to stop. -

DISAPPEAR HERE Violence After Generation X

· · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · DISAPPEAR HERE Violence after Generation X Naomi Mandel THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS / COLUMBUS All Rights Reserved. Copyright © The Ohio State University Press, 2015. Batch 1. Copyright © 2015 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Mandel, Naomi, 1969– author. Disappear here : violence after Generation X / Naomi Mandel. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8142-1286-8 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Violence in literature. 2. Violence—United States—20th century. 3. Generation X— United States—20th century. I. Title. PN56.V53M36 2015 809'.933552—dc23 2015010172 Cover design by Janna Thompson-Chordas Text design by Juliet Williams Type set in Adobe Sabon Printed by Thomson-Shore, Inc. Cover image: Young woman with knife behind foil. © Bernd Friedel/Westend61/Corbis. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSI Z39.48-1992. 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 All Rights Reserved. Copyright © The Ohio State University Press, 2015. Batch 1. To Erik with love and x x x All Rights Reserved. Copyright © The Ohio State University Press, 2015. Batch 1. All Rights Reserved. Copyright © The Ohio State University Press, 2015. Batch 1. contents · · · · · · · · · List of Illustrations vi Acknowledgments vii introduction The Middle Children of History 1 one Why X Now? Crossing Out and Marking the Spot 9 two Nevermind: An X Critique of Violence 41 three The Game That Moves: Bret Easton Ellis, 1985–2010 79 four Something Empty in the Sky: 9/11 after X 111 five Not Yes or No: Fact, Fiction, Fidelity in Jonathan Safran Foer 150 six I Am Jack’s Revolution: Fight Club, Hacking, Violence after X 178 conclusion X Out 210 Works Cited 227 Index 243 All Rights Reserved. -

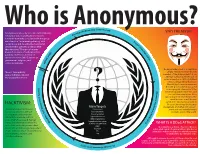

Langis Who Is Anonymous3

Who is Anonymous?atica (2004- Pre ram sent) dia D Anonymous is a loosely associated international lope WHY THE MASK? cyc network of activist and hacktivist entities. En A website nominally associated with the group describes it as "an internet gathering" with P ro "a very loose and decentralized command je ct C structure that operates on ideas rather h a n than directives”. The group became o lo known for a series of well-publicized ) g 3 y 0 ( publicity stunts and distributed 0 2 2 0 denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks on ( 0 N 8 ) government, religious, and A H C corporate websites. 4 The Guy Fawkes mask is a depiction “Anons” have publicly of Guy Fawkes, the best-known supported WikiLeaks and member of the Gunpowder Plot, an the Occupy Movement. attempt to blow up the House of Lords in London in 1605. A stylized version, designed by illustrator David Lloyd, came to represent broader protest after it was used ) t as a major plot element in “V for n O e p s Vendetta”, published in 1982, and e e r r its 2006 lm adaptation. After a P - t i 3 appearing in Internet forums, the o 1 n 0 mask became a well-known : 2 P ( a symbol for Anonymous, used in r y e t HACKTIVISM: b Project Chanology, the Occupy n a i Main Targets c movement, and other anti-govern- k W i Hacktivism (a portmanteau of e US Government s ment and anti-establishment f a a Israeli Government hack and activism) is the use S protests around the world. -

Hacker, Hoaxer, Whistleblower, Spy: the Story of Anonymous

hacker, hoaxer, whistleblower, spy hacker, hoaxer, whistleblower, spy the many faces of anonymous Gabriella Coleman London • New York First published by Verso 2014 © Gabriella Coleman 2014 The partial or total reproduction of this publication, in electronic form or otherwise, is consented to for noncommercial purposes, provided that the original copyright notice and this notice are included and the publisher and the source are clearly acknowledged. Any reproduction or use of all or a portion of this publication in exchange for financial consideration of any kind is prohibited without permission in writing from the publisher. The moral rights of the author have been asserted 1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2 Verso UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201 www.versobooks.com Verso is the imprint of New Left Books ISBN-13: 978-1-78168-583-9 eISBN-13: 978-1-78168-584-6 (US) eISBN-13: 978-1-78168-689-8 (UK) British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A catalog record for this book is available from the library of congress Typeset in Sabon by MJ & N Gavan, Truro, Cornwall Printed in the US by Maple Press Printed and bound in the UK by CPI Group Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY I dedicate this book to the legions behind Anonymous— those who have donned the mask in the past, those who still dare to take a stand today, and those who will surely rise again in the future. -

W Internet Phenomenon

Category: Web Technologies 8015 Internet Phenomenon W Lars Konzack University of Copenhagen, Denmark INTRODUCTION INTERNET MEMES Internet phenomenon is a new field of research. The most common internet phenomenon is an An internet phenomenon is an occurrence on the internet meme. The idea of memes takes it root in internet about somebody, a website, or a picture the memetics of Richard Dawkins but the concept that for some reason captures the attention of of internet memes have evolved since then. Internet numerous internet users and develops a craze that memes has become part of everyday life on the fast-spreads through the internet. The most com- internet. Research has been done to understand this mon internet phenomenon is an internet meme, internet phenomenon as regards the development but also internet celebrities, political campaigns, of internet memes, categorization of memes, and or simply something out of the ordinary. how they work. An Internet meme is defined as a motif that is virally disseminated through the Internet. The BACKGROUND motif often undergoes lots of variations (mash- ups) and may consist of sound, picture, movie clip, Before the internet there were the existence of game and written text, or as is mostly the case, a folk tales and urban legends, folk songs and oral combination by two or more modalities. Moreover poetry as a way share content (Duggan, Haase, & the motif can be connected to only one of these Callow, 2016). Internet phenomenona have often modalities but need not be and in such case may been compared to folklore and urban legends; enter different kinds of modalities. -

The Force of Digital Aesthetics Olga Goriunova

The Force of Digital Aesthetics On Memes, Hacking, and Individuation Olga Goriunova abstract The paper explores memes, digital artefacts that acquire a viral character and become globally popular, as an aesthetic trend that not only entices but propels and molds subjective, collective and political becoming. Following both Simondon and Bakhtin, memes are first considered as aes- thetic objects that mediate individuation. Here, resonance between psychic, collective and technical individuation is established and re-enacted through the aesthetic consummation of self, the collective and the technical in the various performances of meme cultures. Secondly, if memes are followed in the making, from birth to their spill-over onto wider social networks, the very expressive form of meme turns out to be borne by specific technical architec- ture and mannerisms of a small number of platforms, and, most notably, the image board 4chan. The source of memes’ various forms of power is concen- trated here. Memes are intimately linked to 4chan’s /b/ board, the birthplace of Lulzsec and the Anonymous hacking networks. Memes’ architectonics, as an inheritance of a few specific human-technical structures, in turn informs the production of new platforms (memes generators), forms of networked expressions, and aesthetic work in the life cycles of mediation. keywords Bakhtin, Simondon, Guattari, memes, digital aesthetics, hacker, Lulzsec, Anonymous, individuation, subjectivity, viral video, social network Introduction Aesthetic morphogenesis has been entrenched