“The Most Vital Question”: Race and Identity in Occupation Policy Construction and Practice, Okinawa, 1945-1946

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A 'A E Plaque Dedicated at Tule Lake Campsit

• ~ep a 'a e ua e aCID • u National Publication of the Japanese American Citizens Le gu Whole. #2,046 (Vol. 88) Friday June 8. 1979 15 Cent Plaque dedicated at Tule Lake campsit minden II row raasm, economic and event "should not be vi wed with her mother and bro r, ~ pdJtical expkJitatian. and as a propaganda vehicle for ~ can uodernUne the (lOl'tStJt'Utio pi' she was forced go to Tul antees II United Stms citIZeN and ah JAa..'s redress campaign." Lake on a train. Her father ens alib. May the IIIjumoes and buJrul. However, Enomoto urged, had been sent to 8 separate I8tJOn suffered ben! I'Ie\W recur. if the "hard-won acceptance" camp. "It was a bleak life." Plaque placed by the Calif. Dept. II of Nikkei today is "worth any Plrks and Recreation m coopei'Ition she said, "filled with 8 deso Wlth the Northern Califomilt-Westem thing, it should stand the test late feeling. The question I of . Nevada DisttJCt Council. JIqIII1'leSe of a legitimate and aggressive ten asked myself was, 'What's American Cni2ensI..eeaue. May V.lm demand for final vindiction going to happen to us?' " On May 27-the same day It was the phrase, "concen that evacuees were flrSt herd "As it stands DOW, no real . tration camps", that the state vindication has occured, and 1 sincerely hope, however ed into Tule lake in 1942 - department of parks objected Nikkei gathered for a plaque the incarceration of Ameri that tJris plaque dedication to, an objection which was ov p~ dedication ceremony on the can citizens without due will help to heal deep scars ercome by changing it to cess can again happen" (Text now-barren site of the concen "American concentration U:ft when the U.s. -

Wwii Webquest

Name:_____________________________ Period:_____ Date:_______________ WWII WEBQUEST Directions: To begin, hold the CTRL button down and click on the links EUROPEAN THEATRE European Theatre – Battles Click here to complete the chart 1939-1942 Date Description / Summarization Invasion of Poland Battle of Britain Lend-Lease Act & Atlantic Charter Pearl Harbor Battle of Stalingrad 1943-1945 Date Description / Summarization Operation Overlord (D-Day) Liberation of Paris Battle of the Bulge European Theatre – People & Events WWII Summary After WWII Summary Omar Bradley Dwight Eisenhower Charles De Gaulle Bernard Law Montgomery Erwin Rommel George S. Patton D-Day Did You Know – Click here • What does the D mean in D-Day? • Who was Andrew Jackson Higgans and what did he do? • How many men were involved in the D-Day landings? Letters from the Front – Click here • Read some of the letters from the soldiers. What are you reactions? PACIFIC THEATRE Advance of Japan – Click here • When does Japan invade China? French Indochina? • What’s happening in Europe at this time? Pacific Theatre – Battles Click here to complete the chart Date Strategic Importance Outcome Casualties Saipan Battle of Leyte Gulf Philippines Campaign Iwo Jima Okinawa Pacific Theatre – People BRIEF Background Info WWII Summary Emperor Hirohito General Douglas MacArthur Admiral Chester Nimitz Bataan Death March What was the Bataan Death March? Click here How were POWs prepared for life in the camp? Click here for this & all other questions What did POWs do to keep their sanity while in the camp? Why was life horrible? Click on the link on the webpage Who was Henry Mucci? Why was Mucci so tough What was his unit training during training? to do? Rescuers of Bataan Click here Pacific Theatre – Events Answer or Summarize the Following: Describe the Context: Summarize her Experience: Koyu Shiroma and the Battle of Saipan Describe the Strategic Importance: What was Combat Like? Harry George and the Strategic Importance of Iwo Jima Summarize Destined to Die: What Eventually Happened to Mr. -

Hayakawa Replies to Open Letter-Adv. Gov. Brown Snubs Asian Heritage

UtIle Tokyo may have been ire of plot to kill Pres. Carter National Publication of the Japanese American Citizens League Gas shortage postpones Whole #2,043 (Vol. 88) Friday, May 18, 1979 25C U S PostpaId 15 Cents Pilgrimage to Pomona 1m Alllelies "A Day of Remembrance" pi.lgrimage born Little 'r: kyo to Pomona VIa Santa Anita has been postponed from Jun 23 to late November because of the current gasolin hortage here, It Hayakawa replies to open letter-adv. was decided by the steering oommittee which held its first session last week (May 12) at the JACL Regional Office. w........... Heve" that the JAU redress a whole. By their tenaclty, coo.r shoulder of giants. In this case, is Santa Anita and Pomona The pilgrimag will be simi- Sen S.I. Hayakawa issued a committee wouJd be that mor tesy, industry and good sense, Ja sei and Nisei pioneers who created were both served as Army as- Jar to earlier Day of Remem reply of about the same num ally insensitive to "wildly ex panese Americans have created the favorable environment in sembly points for most of the brance programs in Seattle, the favorable atmosphere in which we are now privileged to ber of words to an open letter aggerate the hardship of the which one of the1r members oould live. Japanese Americans being Portland and San Francisa> advertising appearing May 9 Japanese". be elected a senator for California evacuated in 1942 from South- where caravans motored to in the Washington PosL It was Noting that the $25,000 is DO only three dec-Ades after the Pacif "Since the redress committee is em California. -

Founding of the Nevada Wing Civil Air Patrol

Founding of the Nevada Wing Civil Air Patrol Col William E. Aceves II Nevada Wing Historian 25 February 2021 Gill Robb Wilson, described in Blazich’s recent book on the Civil Air Patrol as the ‘intellectual founder’ of the organization, started the ball rolling on the creation of the Civil Air Patrol in 1939. He realized that aviation in the United States would be severely curtailed, if not outright banned, within the country should it be dragged into the wars that were being fought on the sides of the oceans that flanked the U.S. mainland. He sought out other similarly minded individuals and they studied what could be done to utilize civilian general aviation as a very useful tool to support whatever national effort for the upcoming involvement in the two-ocean war would look like. By 1941 some individual states were attempting to do the same within their own boarders, but Wilson, et al, were thinking along the lines of a national organization. They studied with great interest the individual state aviation plans. In Ohio, the Civilian Air Reserve (CAR) had been formed in 1939, and by 1941 other CAR units had been formed in Colorado, Connecticut, Florida, Maine, Massachusetts, New York, and Pennsylvania. These groups, with a military organizational structure, would serve their individual states and remain distant from the military. It was clear that civilian pilots wanted to contribute their skills and their machines to a worthy cause. The Federal government also realized that organizing the civilian side of the house was a necessary priority, and President Roosevelt began creating several agencies and offices to study what was needed to prepare the civilian population for war: The Office of Emergency Management, Council on National Defense, National Defense Advisory Commission, and others, came into existence. -

Battle of Okinawa 1 Battle of Okinawa

Battle of Okinawa 1 Battle of Okinawa Battle of Okinawa Part of World War II, the Pacific War A U.S. Marine from the 2nd Battalion, 1st Marines on Wana Ridge provides covering fire with his Thompson submachine gun, 18 May 1945. Date 1 April – 22 June 1945 Location Okinawa, Japan [1] [1] 26°30′N 128°00′E Coordinates: 26°30′N 128°00′E Result Allied victory, Okinawa occupied by U.S. until 1972 Belligerents United States Empire of Japan United Kingdom Canada Australia New Zealand Commanders and leaders Simon B. Buckner, Jr. † Mitsuru Ushijima † Roy Geiger Isamu Chō † Joseph Stilwell Minoru Ota † Chester W. Nimitz Keizō Komura Raymond A. Spruance Sir Bernard Rawlings Philip Vian Bruce Fraser Strength 183,000 (initial assault force only) ~120,000, including 40,000 impressed Okinawans Casualties and losses More than 12,000 killed More than 110,000 killed More than 38,000 wounded More than 7,000 captured 40,000–150,000 civilians killed The Battle of Okinawa, codenamed Operation Iceberg, was fought on the Ryukyu Islands of Okinawa and was the largest amphibious assault in the Pacific War of World War II. The 82-day-long battle lasted from early April until mid-June 1945. After a long campaign of island hopping, the Allies were approaching Japan, and planned to use Okinawa, a large island only 340 mi (550 km) away from mainland Japan, as a base for air operations on the planned Battle of Okinawa 2 invasion of Japanese mainland (coded Operation Downfall). Four divisions of the U.S. -

America's Decision to Drop the Atomic Bomb on Japan Joseph H

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2007 America's decision to drop the atomic bomb on Japan Joseph H. Paulin Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Paulin, Joseph H., "America's decision to drop the atomic bomb on Japan" (2007). LSU Master's Theses. 3079. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/3079 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AMERICA’S DECISION TO DROP THE ATOMIC BOMB ON JAPAN A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Liberal Arts in The Inter-Departmental Program in Liberal Arts By Joseph H. Paulin B.A., Kent State University, 1994 May 2007 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT……………………………………………………...………………...…….iii CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION……………………………………...………………….1 CHAPTER 2. JAPANESE RESISTANCE………………………………..…………...…5 CHAPTER 3. AMERICA’S OPTIONS IN DEFEATING THE JAPANESE EMPIRE...18 CHAPTER 4. THE DEBATE……………………………………………………………38 CHAPTER 5. THE DECISION………………………………………………………….49 CHAPTER 6. CONCLUSION…………………………………………………………..64 REFERENCES.………………………………………………………………………….68 VITA……………………………………………………………………………………..70 ii ABSTRACT During the time President Truman authorized the use of the atomic bomb against Japan, the United States was preparing to invade the Japanese homeland. The brutality and the suicidal defenses of the Japanese military had shown American planners that there was plenty of fight left in a supposedly defeated enemy. -

THE JERSEYMAN 5 Years - Nr

1st Quarter 2007 "Rest well, yet sleep lightly and hear the call, if again sounded, to provide firepower for freedom…” THE JERSEYMAN 5 Years - Nr. 53 USS NEW JERSEY Primerman - Turret Two... “I was a primerman left gun, and for a short time, in right gun of turret two on the New Jersey. In fact there was a story written by Stars and Stripes on the gun room I worked in about July or August 1986. But to your questions, yes we wore a cartridge belt, the belt was stored in a locker in the turret, and the gun captain filled the belts. After the gun was loaded with rounds, six bags of powder (large bags were 110 lbs. each) and lead foil, the gun elevated down to the platform in the pit where loaded, and the primer was about the same size as a 30-30 brass cartridge. After I loaded the primer I would give the gun captain a "Thumbs up," the gun captain then pushed a button to let them know that the gun was loaded and ready to fire. After three tones sounded, the gun fired, the gun captain opened the breech and the empty primer fell Primer cartridge courtesy of Volunteer into the pit. Our crew could have a gun ready to fire Turret Captain Marty Waltemyer about every 27 seconds. All communicating was done by hand instructions only, and that was due to the noise in the turret. The last year I was in the turrets I was also a powder hoist operator...” Shane Broughten, former BM2 Skyberg, Minnesota USS NEW JERSEY 1984-1987 2nd Div. -

The Invasion That Didn't Happen

Before the atomic bombs brought an end to the war, US troops were set for massive amphibious landings in the Japanese home islands. The Invasion That Didn’t Happen By John T. Correll Gen. Henry H. “Hap” Ar- nold, commander of the Army Air Forces, predicted that the bombing would be sufficient to prevail and “enable our in- Bettmann/Corbis photo fantrymen to walk ashore on Japan with their rifles slung.” Adm. Ernest J. King, Chief of Naval Operations, believed that encirclement, blockade, and bombardment would eventu- ally compel the Japanese to surrender. Others, notably Gen. George C. Marshall, the influential Army Chief of Staff, were convinced an invasion would be necessary. In the summer of 1945, the United States pursued a mixed strategy: con- tinuation of the bombing and blockading, while preparing for an invasion. Japan had concentrated its strength for a decisive defense Emperor Hirohito reviews Japanese troops in Tokyo in June 1941. Only when Japan of the homeland. In June, Tokyo’s leaders suffered severe hardship did his enthusiasm for the war begin to wane. decided upon a fight to the finish, com- mitting themselves to extinction before surrender. As late as August, Japanese here was never any chance Japanese airpower was mostly kamikaze troops by the tens of thousands were that Japan would win World aircraft, although there were thousands pouring into defensive positions on T War II in the Pacific. When of them and plenty of pilots ready to fly Kyushu and Honshu. Japan attacked the US at Pearl Harbor, on suicide missions. Nevertheless, Japan Old men, women, and children were it bit off more than it could chew. -

World War Ii Veteran’S Committee, Washington, Dc Under a Generous Grant from the Dodge Jones Foundation 2

W WORLD WWAR IIII A TEACHING LESSON PLAN AND TOOL DESIGNED TO PRESERVE AND DOCUMENT THE WORLD’S GREATEST CONFLICT PREPARED BY THE WORLD WAR II VETERAN’S COMMITTEE, WASHINGTON, DC UNDER A GENEROUS GRANT FROM THE DODGE JONES FOUNDATION 2 INDEX Preface Organization of the World War II Veterans Committee . Tab 1 Educational Standards . Tab 2 National Council for History Standards State of Virginia Standards of Learning Primary Sources Overview . Tab 3 Background Background to European History . Tab 4 Instructors Overview . Tab 5 Pre – 1939 The War 1939 – 1945 Post War 1945 Chronology of World War II . Tab 6 Lesson Plans (Core Curriculum) Lesson Plan Day One: Prior to 1939 . Tab 7 Lesson Plan Day Two: 1939 – 1940 . Tab 8 Lesson Plan Day Three: 1941 – 1942 . Tab 9 Lesson Plan Day Four: 1943 – 1944 . Tab 10 Lesson Plan Day Five: 1944 – 1945 . Tab 11 Lesson Plan Day Six: 1945 . Tab 11.5 Lesson Plan Day Seven: 1945 – Post War . Tab 12 3 (Supplemental Curriculum/American Participation) Supplemental Plan Day One: American Leadership . Tab 13 Supplemental Plan Day Two: American Battlefields . Tab 14 Supplemental Plan Day Three: Unique Experiences . Tab 15 Appendixes A. Suggested Reading List . Tab 16 B. Suggested Video/DVD Sources . Tab 17 C. Suggested Internet Web Sites . Tab 18 D. Original and Primary Source Documents . Tab 19 for Supplemental Instruction United States British German E. Veterans Organizations . Tab 20 F. Military Museums in the United States . Tab 21 G. Glossary of Terms . Tab 22 H. Glossary of Code Names . Tab 23 I. World War II Veterans Questionnaire . -

Sec Row Num Victor E

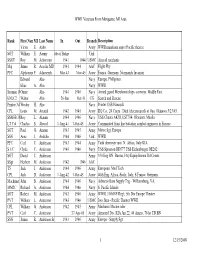

Rank and Name Line One Line Two Line Three In Out Brnch Description Sec Row Num Victor E. Aalto VICTOR AALTO WWII Army WWII munitions supvr Pacific theatre 7 E 42 SGT William E. Aarmy WM E CUYLER SGT WWIIWWII, ARMY combat inf. Europe, Dday, Battle of Bulge 1 1 7 CPRL Aarno J. Aartila CPRL AARNO J AARTILA USMC 1952 1954 USMC 6 19 ADAN Richard F. Aartila AN RICHARD F AARTILA USN 1951 1955 USN 6 20 SSGT Roy M. Ackerman ROY ACKERMAN SGT USMC WWII 1941 1944 USMC Aircraft mechanic 1 58 5 Maj James R. Acocks MD JAMES ACOCKS MAJ WWII 1941 1944 Army AF Flight Physician 2 28 1 PFC Alphonsus F. Adamezyk AL ADAMCZYK WWII 101ST POW Mar-43 Nov-45 Army France, Germany, Normandy Invasion. 5 19 5 Elias A. Aho ELIAS A AHO USN WWII Navy WWII 7 S 3 CPL Elmer M. Aho ELMER M AHO CPL US ARMY 18-Apr-52 25-Mar-54 Army Korean War 1 1 6 Chateauroux France, Bentwater AFB, England. A2C Gary E. Aho GARY E AHO USAF 1962-65 1962 1965 USAF Acft Mech 6 25 BT3 Tim A. Aho BT3 TIM AHO US NAVY 1970 1974 Navy Vietnam War 1 59 6 ENLC2 Walter Aho WALTER AHO ENLC2 WWII 26-Jun Oct-51 USCG Search and Rescue 1 57 6 EN1 Walter P. Aho WALT AHO JR EN1 VIETNAM Jul-63 Jul-67 USCG Search and Rescue 1 55 6 Connie J. Aho CONNIE J AHO JOHNSON USN 1980 1984 Navy California, Florida, Japan 7 S 4 Atch to submarine at Pearl Harbor. -

Clete Roberts Papers, 1938-1986

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt5k4022s2 No online items Finding Aid for the Clete Roberts Papers, 1938-1986 Processed by Elizabeth Sheehan, with assistance from Laurel McPhee, 2005; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé. UCLA Library Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.library.ucla.edu/libraries/special/scweb/ © 2006 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid for the Clete Roberts 1288 1 Papers, 1938-1986 Descriptive Summary Title: Clete Roberts Papers Date (inclusive): 1938-1986 Collection number: 1288 Creator: Roberts, Clete, 1912-1984. Extent: 33 boxes (16.5 linear ft.)2 oversize boxes. Abstract: Clete Roberts (1912-1984) was a broadcast journalist and documentary filmmaker. The collection consists of broadcast scripts, reporter's notes, research materials, contracts, correspondence, articles and publicity material, awards, printed matter and ephemera, financial and legal documents, photographs, and audio reels and cassettes. Language: Finding aid is written in English. Repository: University of California, Los Angeles. Library. Department of Special Collections. Los Angeles, California 90095-1575 Physical location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact UCLA Library Special Collections for paging information. Restrictions on Access Open for research. STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact UCLA Library Special Collections for paging information. Restrictions on Use and Reproduction Property rights to the physical object belong to the UCLA Library, Department of Special Collections. -

WWII Veterans from Marquette, MI Area Rank First Amemi Last Ame in out Branch Description Victor E. Aalto Army WWII Munitions Su

WWII Veterans From Marquette, MI Area Rank First ameMI Last ame In Out Branch Description Victor E. Aalto Army WWII munitions supvr Pacific theatre SGTWWII, combat William inf. Europe, E. Aarmy Dday, Battle of Bulge Unk SSGT Roy M. Ackerman 1941 1944 USMC Aircraft mechanic Maj James R. Acocks MD 1941 1944 AAC Flight Phy PFC Alphonsus F. Adamezyk Mar-43 Nov-45 Army France, Germany, Normandy Invasion. Edward Aho Navy Europe, Phillipines Elias A. Aho Navy WWII Seaman 1ClassOnnie Aho 1944 1946 Navy Armed guard Merchanat ships- convoys. Middle East. ENLC2 Walter Aho 26-Jun Oct-51 CG Search and Rescue Printer 3d Wesley H. Aho Navy Printer USS Hancock CPL Louis M. Airaudi 1942 1945 Army HQ Co., 24 Corps. Died (electrocuted) at Osa, Okinawa 5/23/45. SSM-B 3C Roy L. Alanen 1944 1946 Navy USS Chaara AK58, LST704. Okinawa, Manila LT Col Charles B. Alvord 1-Aug-41 1-Oct-45 Army Commanded front line battalion combat engineers in Europe SGT Paul G. Ameen 1943 1945 Army Motor Sgt, Europe SSG Arne J. Andelin 1944 1946 Unk WWII PFC Carl C. Anderson 1943 1944 Army Tank destroyer unit. N. Africa, Italy.KIA S 1/C Clyde C. Anderson 1945 1946 Navy USS Sproston DD577 USS Eichenberger DE202 SGT David C. Anderson Army 330 Eng BN. Burma. Hvy Equip Burma Rd Constr. SSgt Herbert M. Anderson 1942 1946 AAC T5 Jack I. Anderson 1944 1946 Army European. Med Tech CPL Jack D. Anderson 1-Aug-42 1-Oct-45 Army 40th Eng. Africa, Sicily, Italy, S France, Germany.