Evidence Based Policy Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

$1 Billion to Billionaire Adani

CAIRNS ONLY THE LNP WILL HAND $1 BILLION TO BILLIONAIRE ADANI We need more investment in local jobs and services, but it seems like the LNP are more interested in taking care of their billionaire mates. The LNP hasn’t changed since the Campbell Newman days.1 Public funds should go to the community - not bailouts for billionaires. To stop Adani’s billion-dollar bailout, VOTE AGAINST THE LNP Here’s how: INDEPENDENT OR LABOR OR THE GREENS Rob Pyne BALLOT PAPER BALLOT PAPER BALLOT PAPER Electoral District of Electoral District of Electoral District of CAIRNS CAIRNS CAIRNS HODGE, Ian HODGE, Ian HODGE, Ian 5 PAULINE HANSON’S ONE NATION 5 PAULINE HANSON’S ONE NATION 5 PAULINE HANSON’S ONE NATION MCDONALD, Aaron MCDONALD, Aaron MCDONALD, Aaron 2 THE GREENS 3 THE GREENS 1 THE GREENS HEALY, Michael HEALY, Michael HEALY, Michael 3 AUSTRALIAN LABOR PARTY 1 AUSTRALIAN LABOR PARTY 3 AUSTRALIAN LABOR PARTY PYNE, Rob PYNE, Rob PYNE, Rob 1 2 2 MARINO, Sam MARINO, Sam MARINO, Sam 4 LNP 4 LNP 4 LNP Why these candidates? To determine who appears on this how to vote card, parties and candidates were researched and surveyed for their position on 26 policy areas. These are the candidates who pledged to block the $1 billion loan for Adani. For more information and the full results of the survey go to: getup.org.au/qld-votes Remember to number every box to make your vote count. Authorised by E. Roberts, 3/15 Lamington St, New Farm, QLD. 1Why was Newman handing out billions to a coal mining company that didn’t need it? — The Guardian, February 2015 GetUp is a campaigning community of over one million Australians working towards a fair, flourishing and just Australia led by the values and hopes of everyday people. -

PDF File (325.6

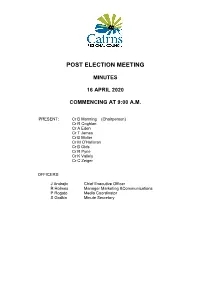

POST ELECTION MEETING MINUTES 16 APRIL 2020 COMMENCING AT 9:00 A.M. PRESENT: Cr B Manning (Chairperson) Cr R Coghlan Cr A Eden Cr T James Cr B Moller Cr M O’Halloran Cr B Olds Cr R Pyne Cr K Vallely Cr C Zeiger OFFICERS: J Andrejic Chief Executive Officer R Holmes Manager Marketing &Communications P Rogato Media Coordinator S Godkin Minute Secretary TABLE OF CONTENTS DECLARATION OF OFFICE AND ADDRESS BY CR MANNING ................................. 3 DECLARATION OF OFFICE AND ADDRESS BY CR MOLLER ................................... 5 DECLARATION OF OFFICE AND ADDRESS BY CR PYNE ........................................ 6 DECLARATION OF OFFICE AND ADDRESS BY CR ZEIGER ..................................... 6 DECLARATION OF OFFICE AND ADDRESS BY CR JAMES ...................................... 7 DECLARATION OF OFFICE AND ADDRESS BY CR EDEN ........................................ 7 DECLARATION OF OFFICE AND ADDRESS BY CR VALLELY .................................. 9 DECLARATION OF OFFICE AND ADDRESS BY CR O’HALLORAN ........................ 10 DECLARATION OF OFFICE AND ADDRESS BY CR COGHLAN .............................. 11 DECLARATION OF OFFICE AND ADDRESS BY CR OLDS ...................................... 11 AGENDA ITEMS AS LISTED 1. ELECTION OF DEPUTY MAYOR ........................................................................ 12 A Agius | 65/4/1-03 | #6322691 2. DAY AND TIME OF ORDINARY MEETINGS....................................................... 12 A Agius | 65/4/1-03 | #6322702 3. COUNCIL STANDING COMMITTEE STRUCTURE ............................................ -

Induced Abortion in Australia: 2000-2020 Published by Family Planning NSW 328-336 Liverpool Road, Ashfield NSW 2131, Australia Ph

Publication Information Induced abortion in Australia: 2000-2020 Published by Family Planning NSW 328-336 Liverpool Road, Ashfield NSW 2131, Australia Ph. (02) 8752 4300 www.fpnsw.org.au ABN: 75 000 026 335 © Family Planning NSW 2021 Suggested citation: Wright, S. M., Bateson, D., & McGeechan, K. (2021). Induced abortion in Australia: 2000-2020. Family Planning NSW: Ashfield, Australia. Acknowledgements: Authors: Sarah M. Wright, Research Officer, Family Planning NSW Deborah Bateson, Medical Director, Family Planning NSW Kevin McGeechan, Consultant Biostatistician, Family Planning NSW Internal review: The production of this document would not have been possible without the contributions of the following members of Family Planning NSW staff: Dr Yan Cheng, Senior Research Officer, Family Planning NSW Dr Clare Boerma, Associate Medical Director, Family Planning NSW 1 Contents Data used in this report ____________________________________________________ 3 Key indicators ________________________________________________________________ 3 Primary data sources ___________________________________________________________ 3 Purpose of this report __________________________________________________________ 4 Terms and definitions __________________________________________________________ 4 Data sources and limitations ____________________________________________________ 5 State government abortion notification ______________________________________________________ 5 Medicare Benefits Schedule and Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme data ___________________________ -

Abortion Law Reform)

Health (Abortion Law Reform) Amendment Bill 2016 Report No. 33, 55th Parliament Health, Communities, Disability Services and Domestic and Family Violence Prevention Committee February 2017 Health, Communities, Disability Services and Domestic and Family Violence Prevention Committee Chair Ms Leanne Linard MP, Member for Nudgee Deputy Chair Mr Mark McArdle MP, Member for Caloundra Members Mr Aaron Harper MP, Member for Thuringowa Mr Sidney (Sid) Cramp MP, Member for Gaven Ms Leanne Donaldson MP, Member for Bundaberg Dr Mark Robinson MP, Member for Cleveland Committee Staff Ms Sue Cawcutt, Inquiry Secretary Ms Trudy Struber, Inquiry Secretary Ms Julie Fidler, Committee Support Officer Ms Mishelle Young, Committee Support Officer Technical Scrutiny Ms Renee Easten, Research Director Secretariat Ms Marissa Ker, Principal Research Officer Ms Lorraine Bowden, Senior Committee Support Officer Contact Details Health, Communities, Disability Services and Domestic and Family Violence Prevention Committee Parliament House George Street Brisbane Qld 4000 Telephone +61 7 3553 6626 Fax +67 7 3553 6639 Email [email protected] Web www.parliament.qld.gov.au/hcdsdfvpc Health (Abortion Law Reform) Amendment Bill 2016 Contents Abbreviations and glossary 4 Chair’s foreword 5 1. Introduction 7 1.1 Role of the committee 7 1.2 Referral and committee’s process 7 1.3 Outcome of committee considerations 7 2. Policy context for the Bill 9 2.1 Committee consideration of Abortion (Woman’s Right to Choose) Amendment Bill 2016 9 2.2 Resolution of the Legislative -

Crimes Act 1958 (Vic), Ss 65 & 66; Crimes Act 1900 (NSW), Ss 82-84; and Crimes Act 1900 (ACT), Ss 42-44

Contemporary Australian Abortion Law: The Description of a Crime and the Negation of a Woman's Right to Abortion MARK J RANKIN* This article provides an up-to-date statement of the law with regard to abortion in Australia. The law in each jurisdiction is canvassed and discussed, with particular emphasis upon the most recent developments in the law. In doing so, two aspects of Australian abortion law are highlighted: first, that abortion is a criminal offence; and second, that therefore Australian law denies women a right to abortion. The article dispels the myth that there exists 'abortion-on-demand' in Australia, and argues that any 'rights' that exist with respect to the practice of abortion are possessed and exercised by the medical profession, and not by pregnant women. INTRODUCTION Abortion is a subject which elicits diverse responses. The myriad legal, political, social, religious, economic, and moral issues that abortion raises are well known to all those who seriously contemplate the subject. This article will, however, concentrate on the legal regulation of abortion. It aims to provide a comprehensive and up-to-date statement of the law with regard to abortion in every jurisdiction in Australia. In doing so, the article will highlight two aspects, or consequences, of the law with regard to abortion: first, that abortion is a criminal offence; and second, that therefore Australian law denies women a right to abortion. The fact that abortions in Australia are widespread and Medicare funded' suggests that there exists a substantial gap between abortion practice and the letter of the law.' This is clearly an issue of concern, but it will not be dealt with in this work. -

Ap2 Final 16.2.17

PALASZCZUK’S SECOND YEAR AN OVERVIEW OF 2016 ANN SCOTT HOWARD GUILLE ROGER SCOTT with cartoons by SEAN LEAHY Foreword This publication1 is the fifth in a series of Queensland political chronicles published by the TJRyan Foundation since 2012. The first two focussed on Parliament.2 They were written after the Liberal National Party had won a landslide victory and the Australian Labor Party was left with a tiny minority, led by Annastacia Palaszczuk. The third, Queensland 2014: Political Battleground,3 published in January 2015, was completed shortly before the LNP lost office in January 2015. In it we used military metaphors and the language which typified the final year of the Newman Government. The fourth, Palaszczuk’s First Year: a Political Juggling Act,4 covered the first year of the ALP minority government. The book had a cartoon by Sean Leahy on its cover which used circus metaphors to portray 2015 as a year of political balancing acts. It focussed on a single year, starting with the accession to power of the Palaszczuk Government in mid-February 2015. Given the parochial focus of our books we draw on a limited range of sources. The TJRyan Foundation website provides a repository for online sources including our own Research Reports on a range of Queensland policy areas, and papers catalogued by policy topic, as well as Queensland political history.5 A number of these reports give the historical background to the current study, particularly the anthology of contributions The Newman Years: Rise, Decline and Fall.6 Electronic links have been provided to open online sources, notably the ABC News, Brisbane Times, The Guardian, and The Conversation. -

2015 Statistical Returns

STATE GENERAL ELECTION Held on Saturday 31 January 2015 Evaluation Report and Statistical Return 2015 State General Election Evaluation Report and Statistical Return Electoral Commission of Queensland ABN: 69 195 695 244 ISBN No. 978-0-7242-6868-9 © Electoral Commission of Queensland 2015 Published by the Electoral Commission of Queensland, October 2015. The Electoral Commission of Queensland has no objection to this material being reproduced, made available online or electronically but only if it is recognised as the owner of the copyright and this material remains unaltered. Copyright enquiries about this publication should be directed to the Electoral Commission of Queensland, by email or in writing: EMAIL [email protected] POST GPO Box 1393, BRISBANE QLD 4001 CONTENTS Page No. Part 1: Foreword ..........................................................................................1 Part 2: Conduct of the Election ....................................................................5 Part 3: Electoral Innovation .......................................................................17 Part 4: Improvement Opportunities............................................................25 Part 5: Statistical Returns ..........................................................................31 Part 6: Ballot Paper Survey .....................................................................483 PART 1 FOREWORD 1 2 PART 1: FOREWORD Foreword The Electoral Commission of Queensland is an independent body charged with responsibility for the impartial -

Never, Ever, Again... Why Australian Abortion Law Needs Reform Caroline De Costa Boolarong Press (2010) 168 Pages; ISBN 9781921555510

CSIRO PUBLISHING Book Review www.publish.csiro.au/journals/sh Sexual Health, 2011, 8, 133–135 Never, Ever, Again... Why Australian Abortion Law Needs Reform Caroline de Costa Boolarong Press (2010) 168 pages; ISBN 9781921555510 The delight of this book stems from the authorial skills of the women who died. It takes the persistence of an historian, the Professor Caroline de Costa. She is a renaissance woman, a eye of the clinician and the wordsmithing of a novelist to bring scholar, clinician, historian and novelist and she brings all these these tales out from the Archives into public view. They are part skills to her review of the impact of laws restricting abortion of the untold story of women in this country, our mothers and in Queensland. As an experienced author she makes the topic grandmothers and their mothers and grandmothers who did what immediately relevant by starting with a personal story, that they had to when they had no option, and died in the doing. of a young woman, Tegan Leach, 21, from Cairns, who in For those with a greater interest in current access to abortion October 2010 faced a criminal trial charged with conducting an de Costa reviews the role of Children by Choice in organizing illegal abortion on herself under Section 225 of the Queensland abortion access for Queensland women when it was not Criminal Code. Such a charge had not been laid in Queensland available in their state. This is a grand account of citizens’ since the abortion laws were consolidated in 1899 and Professor action in the face of government and police obduracy. -

2017 Abortion Law in Australia 2017

Abortion Law in Australia Research Paper 1 1998-99 Natasha Cica Law and Bills Digest Group 31 August 1998 Contents Major Issues Summary Introduction Unlawful Abortion The Crime of Unlawful Abortion The (changing) Meaning of Unlawful Abortion in Australia Child Destruction The English Model - Victoria and South Australia The Code Jurisdictions - Western Australia, Queensland, the Northern Territory and Tasmania The ACT and NSW Homicide Endnotes Major Issues Summary The vexed question of abortion law reform was unexpectedly back in the news in Australia earlier this year. In February 1998 it was announced that two Perth doctors were to be prosecuted under the Western Australian laws that make abortion a crime. These were the first charges laid against medical practitioners under those Western Australian laws in over 30 years. The political events that followed this decision ultimately culminated in the passage by the Western Australian parliament of legislation introducing what is in many respects the most liberal abortion law in Australia. The legislation originated as a Private Member's Bill introduced into the upper house of the Western Australian parliament by Cheryl Davenport MLC (ALP). The legislation passed with some amendments on 20 May 1998. The question of when, if ever, performing an abortion will be morally justified is one that endlessly consumes many philosophers, theologians, feminists, social scientists and legal commentators. It is also a question that a large number of Australian women address every day in a more applied sense: when they are making an actual decision about whether to continue an unplanned pregnancy. Like many other medical and moral decisions that people make, each woman's abortion decision is made in the context of complex-and sometimes conflicting-personal and societal values. -

Legislative Assembly

LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY ETHICS COMMITTEE Report No. 179 Report on a Right of Reply No. 34 Introduction and Background 1. The Legislative Assembly provides a right of reply to persons and corporations who are the subject of adverse comment in Parliament. The Ethics Committee (the committee) has responsibility for advising the Assembly regarding submissions for a right of reply. 2. The right of reply relates to statements made by members under parliamentary privilege. Persons or corporations who are named, or referred to in such a way as to be readily identified and who consider their reputation has been adversely affected, may request a right of reply. Procedure 3. Chapter 46 of theStanding Rules and Orders of the Legislative Assembly, effective from 31 August 2004 (the Standing Orders), sets out the operation of the right of reply for persons and corporations and the procedure for the committee to foilow when considering submissions. 4. Standing Order 282(5) provides that the committee is not to consider or judge the truth of any statements made in the House or the submission when considering a submission for a right of reply. 5. Under Standing Order 283, the committee may recommend— • that no further action be taken by the committee or the House in relation to the submission; or • that a response by the person who made the submission, in terms specified in the committee's report and agreed to by the person or corporation and the committee, be incorporated in the Record of Proceedings or published in some other manner. Referral 6 . Mr Max Barrie wrote to Speaker Wellington on 6 September 2017 (55*'’ Parliament) to seek a citizen's right of reply to a statement made in a document titled 'Council - Cook Shire Council' tabled by the then Member for Cairns, Mr Rob Pyne MP, on 24 August 2017. -

A Year in Review for the PERIOD 1 July 2015 – 30 JUNE 2016

2015-16: A year in review FOR THE PERIOD 1 JULY 2015 – 30 JUNE 2016 Report OF THE QUEENSLAND NURSES’ UNION OF EMployees AND Australian NURSING AND MIDWIFERY Federation (QNU BRANCH) 35th ANNUAL CONFERENCE 13-15 JULY 2016 BRISBANE CONVENTION AND EXHIBITION CENTRE Introduction It’s quite surprising when you begin to look back over the year’s events to realise just how much you can squeeze into 12 months. Let’s take a moment to reflect. This year … We made history by securing legislated nurse-to-patient and midwife-to-patient ratios. We finalised public sector award modernisation without loss of conditions. We took the public sector EB9 to ballot. Beth Mohle We engaged in one of the longest federal election campaigns in Australian history. In any other year, any one of these would have been achievement enough—but to have all of them come to fruition in one year is quite the feat. And it doesn’t end there. While those big issues were in the spotlight, the important day-to-day work of our union has also been tracking very well. Our membership numbers have reached a record 56,000, we’ve negotiated 34 private, aged care and other enterprise agreements, our social media community has doubled since last year, and our member services and legal team have increased their caseload by about 25%. While it is true the absence of a truly adversarial state government did allow us to turn our focus elsewhere, the secret to our successes this year, and every year, runs deeper than that. -

Background on the Australian Christian Lobby

National Office 4 Campion Street Deakin ACT 2600 T 02 6259 0431 E [email protected] ABN 40 075 120 517 29 June 2016 Research Director Health, Communities, Disability Services and Domestic and Family Violence Prevention Committee Parliament House George Street Brisbane Qld 4000 Re: Abortion Law Reform (Women's Right to Choose) Amendment Bill 2016 Background on the Australian Christian Lobby The Australian Christian Lobby (ACL) is a grassroots movement of over 68,000 people seeking to bring a Christian influence to politics. We want to see Christian principles and ethics accepted and influencing the way we are governed, do business and relate as a society. We want Australia to become a more just and compassionate nation. ACL is a non-party partisan, non-denominational movement that seeks to bring a credible, Christian voice for values to our national debate. Abortion Law Reform (Women's Right to Choose) Amendment Bill 2016 The Australian Christian Lobby (ACL) welcomes the opportunity to provide a submission to the committee on the private members bill Abortion Law Reform (Women's Right to Choose) Amendment Bill 2016 and the committee’s consideration on various aspects of law governing abortion. The bill introduced by Mr Rob Pyne MP, Member for Cairns, Abortion Law Reform (Women's Right to Choose) Amendment Bill 2016, would remove 3 abortion related offences from the Criminal Code, as well as remove disqualifying offences from the Transport Operations (Road Use Management) Act 1995. ACL recommends this bill not be passed. A recent e-petition opposing this bill closed on 23 May 2016 and received 23,869 signatures, a very high number of signatures for any QLD petition.