Context Document for Civil Rights in Ohio

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Woman War Correspondent,” 1846-1945

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Carolina Digital Repository CONDITIONS OF ACCEPTANCE: THE UNITED STATES MILITARY, THE PRESS, AND THE “WOMAN WAR CORRESPONDENT,” 1846-1945 Carolyn M. Edy A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Journalism and Mass Communication. Chapel Hill 2012 Approved by: Jean Folkerts W. Fitzhugh Brundage Jacquelyn Dowd Hall Frank E. Fee, Jr. Barbara Friedman ©2012 Carolyn Martindale Edy ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii Abstract CAROLYN M. EDY: Conditions of Acceptance: The United States Military, the Press, and the “Woman War Correspondent,” 1846-1945 (Under the direction of Jean Folkerts) This dissertation chronicles the history of American women who worked as war correspondents through the end of World War II, demonstrating the ways the military, the press, and women themselves constructed categories for war reporting that promoted and prevented women’s access to war: the “war correspondent,” who covered war-related news, and the “woman war correspondent,” who covered the woman’s angle of war. As the first study to examine these concepts, from their emergence in the press through their use in military directives, this dissertation relies upon a variety of sources to consider the roles and influences, not only of the women who worked as war correspondents but of the individuals and institutions surrounding their work. Nineteenth and early 20th century newspapers continually featured the woman war correspondent—often as the first or only of her kind, even as they wrote about more than sixty such women by 1914. -

The Honorable Harold H. Greene

THE HONORABLE HAROLD H. GREENE U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia Oral History Project The Historical Society of the District of Columbia Circuit Oral History Project United States Courts The Historical Society of the District of Columbia Circuit District of Columbia Circuit The Honorable Harold H. Greene U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia Interviews conducted by: David Epstein, Esquire April 29, June 25, and June 30, 1992 NOTE The following pages record interviews conducted on the dates indicated. The interviews were electronically recorded, and the transcription was subsequently reviewed and edited by the interviewee. The contents hereof and all literary rights pertaining hereto are governed by, and are subject to, the Oral History Agreements included herewith. © 1996 Historical Society of the District of Columbia Circuit. All rights reserved. PREFACE The goal of the Oral History Project of the Historical Society of the District of Columbia Circuit is to preserve the recollections of the judges who sat on the U.S. Courts of the District of Columbia Circuit, and judges’ spouses, lawyers and court staff who played important roles in the history of the Circuit. The Project began in 1991. Most interviews were conducted by volunteers who are members of the Bar of the District of Columbia. Copies of the transcripts of these interviews, a copy of the transcript on 3.5" diskette (in WordPerfect format), and additional documents as available – some of which may have been prepared in conjunction with the oral history – are housed in the Judges’ Library in the United States Courthouse, 333 Constitution Avenue, N.W., Washington, D.C. -

Finding Aid for the Cleveland Press Photograph Collection

Finding aid for the Cleveland Press Photograph Collection Repository: Cleveland State University Title: Cleveland Press Photograph Collection Inclusive Date(s): 1920-1982 Author: Finding aid prepared by Lynn Duchez Bycko Creation: Finding aid encoded by Kiffany Francis using the OhioLINK EAD Application in 2009 Descriptive Rules: Finding aid prepared using Finding aid prepared using Describing Archives: A Content Standard. Origination: Cole, Joseph E. Extent: 882 linear feet Physical Location: Abstract: After the Cleveland Press newspaper ceased publication on June 17, 1982. Joseph E. Cole, its publisher, donated the "morgue" to Cleveland State University. Representing the archived editorial library, sometimes referred to as a "newspaper morgue," topics focus on the news coverage of northeastern Ohio, with national and international news stories holding a secondary level of importance.The Cleveland Press photograph collection is composed of an archive of over one million photographs. Unit ID: PH2000.000PRE Language(s) of the Materials: English History of The Cleveland Press The Cleveland Press, founded by Edward W. Scripps, began as the Penny Press on 2 Nov. 1878. A small, 4-page afternoon daily, the paper continued to prosper. Shortened to the Press in 1884, and finally the Cleveland Press in 1889, by 1903 the Press was Cleveland's leading daily newspaper. As it entered the 1920s, the Press neared 200,000 in circulation. Louis B. Seltzer became the 12th editor of the Press in 1928, and under his 38-year stewardship the Press became one of the country's most influential newspapers. Seltzer readjusted its original working-class bias into a less controversial neighborhood orientation, stressing personal contacts and promoting the slogan "The Newspaper That Serves Its Readers." In the postwar period the Press continued its public service campaigns and remained an unrivaled force in Ohio politics. -

Rivers & Lakes

Rivers & Lakes Theme: Water Quality and Human Impact Age: Grade 3-6 Time: 3 hours including time for lunch Funding The Abington Foundation has funded this program for the STEAM Network to include all third grade classes in the Network. This grant covers professional development, pre and post visit activities, Lakes & Rivers program at the aquarium, transportation, and a family event with the Greater Cleveland Aquarium. The Greater Cleveland Aquarium Splash Fund is the recipient and fiscal agent for this grant from The Abington Foundation. The final report is due November 2015. Professional Development A one and a half hour teacher workshop is in place for this program. It was first presented to 4 teachers at the Blue2 Institute on July 30 by Aquarium staff. We are prepared to present it again this fall to prepare teachers for this experience. Teachers were presented with lesson plans, pre and posttests, and a water quality test kits to prepare their students to the Lakes and Rivers program. Lakes & Rivers program Overview Explore the rich history of Ohio’s waterways while journeying through Lake Erie, and the Cuyahoga River. This program will explore the deep interconnection that Ohio has with its freshwater systems through time. Students will use chemical tests to determine the quality of Cuyahoga River water and learn about Ohio’s native fish, amphibians, reptiles, through hands-on activities that teach students the importance of protecting our local waters. Standards Ohio’s Learning Standards Content Statements in science, social studies and math covered in Lakes and River s are listed below. -

Harrison Park

Harrison Park Harrison West Society Park Committee Formed in association with the Harrison West Society and Wagenbrenner Development to plan and develop a new 4.6-Acre waterfront park. Harrison Park will run along the Olentangy River from Second Avenue on the North to Quality Place to the South. The park will be developed through a joint venture between the developer and the community, funded by Tax Increment Financing. The Harrison West Park Committee will be responsible for the development of a purpose and need statement for the direction of the TIF. The park upon completion will be dedicated to the City of Columbus for public use. Harrison West Society Park Committee Table of Contents: Park Committee Members 2003 1 Tax Increment Finance News Article 33 Parkland Dedication 2003 2 Presentation to Recreation & Parks 34 Committee Park Names 3 Presentation to Victorian Village 35, 36 City of Columbus Park Names 4 Presentation to Harrison West 37 Park Naming Criteria & Endings 5 Gowdy Field 38 Program & Direction 6 Columbus Urban Growth Letter 39, 40 Plan Evaluation by Officers 7 Harrison Park Center 41, 42 Plan Evaluation by Committee 8 Park Details 43-47 Park Naming 9 Gowdy Field Selection Committee 48 Tax Increment Finance Priorities 10 Gowdy Field News Article 49, 50 Tax Increments Finance Q & A 11, 12 Gowdy Field Request for Qualifications 51-53 Park Details 13, 14 Side by Side Park 54, 55 Gazebo Options 15, 16 Street Lighting 56 Recreation & Parks Comments 17 Avenue One Lofts conceptual proposal 57-62 Site Visit Cancelled 18 Avenue -

Armco's Semi-Pro Teams

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol. 10, No. 2 (1988) ARMCO'S SEMI-PRO FOOTBALL TEAMS Courtesy of Armco Corp. The fervor for sports which pervaded the Ashland and Middletown communities in the twenties caused the Armco Associations of both cities, in the fall of 1924, to sponsor and develop semi-professional football teams. The majority of the players were in the employ of the Company. It was an era when the Canton Bulldogs and the Ironton Tanks were nationally known for their prowess in the professional football field. The Portsmouth Spartans and the Dayton Triangles were also severe competition. From 1924 to 1929 the Ashland and Middletown teams were maintained at high efficiency, and their home matches drew large crowds. The rivalry between Ashland and Middletwon was keen, and the records show that Ashland won six to Middletown's two over the years. Some understanding as to the semi-pro calibre of Armco football can be gained from the roster of college players on the Middletwon "Armco Blues" during the five years it was promoted. They included: Forest McGuire, Swathmore; Johnie Becker, Dennison; Dal Gardner, University of Illinois; Pick Reiter, Miami; Joe Cox, Ohio State; Wyatt McCall, Miami; Johnnie Schott, University of Cincinnati; Jerry Tobin, Purdue; "Pude" Beatty, St. Xavier; Wendell Tussing, Georgia Tech; Ad Strosnider, University of Dayton; Buford Potts, University of Missouri; Mat Alger, St. Xavier; Ward Brashares, Miami; Mark Crawford, Purdue; "Swede" Fredirckson, Miami; Pup Graham, Chicago Cardinals; Howard Heavy, University of Cincinnati; Pat Marts, Ohio State; Tom Mincher, Miami; Jim McMillan, Purdue; Clifford Morgan, University of Missouri; Don O'Brien, Purdue; Earl Sullivan, St. -

National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form

14 NNP5 fojf" 10 900 ft . OW8 Mo 1024-00)1 1 (J United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form This form is for use in documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in Guidelines for Completing National Register Forms (National Register Bulletin 16). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the requested information. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Type all entries. A. Name of Multiple Property Listing Short North Mulitipie Property Area.__________________ B. Associated Historic Contexts Street car Related Development 1871-1910________________________ Automotive Related Development 1911-1940 ______ C. Geographical Data___________________________________________ The Short North area is located in Columbus, Franklin County, Ohio. It is a corridor of North High Street located between Goodale Street and King Avenue. The corridor is situated between the Ohio State University Area on the North and Downtown Columbus on the South. The Near North Side National Register Historic District is situated immediately to the west and Italian Village is local historic district to the east. King Avenue has traditionally been a dividing line between the Short North and University sections of North High Street. Interstate 670 which runs parallel with and under Goodale forms a sharp divider between Downtown and the Short North. Italian Village and the Near North Side District are distinctly residential neighborhoods that adjoin this commercial corridor. LjSee continuation sheet 0. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966. -

University Microfilms, a XEROX Company , Ann Arbor, Michigan

71-7525 MURPHY, Melvin L. , 1936- THE COLUMBUS URBAN LEAGUE: A HISTORY, 1917-1967. The Ohio State University,Ph.D., 1970 H isto r y , modern University Microfilms, A XEROX Company , Ann Arbor, Michigan Copyright by Melvin L. Murphy 1971 THE COLUMBUS URBAN LEAGUE: A HISTORY, 1917-1967 DISSERTATION Presented In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy In the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Melvin L. Murphy, B.A., M.A. ****** The Ohio State University 1970 Approved by Adviser Deparlroent of History ACKNOWLEDGMENT I express thanks to many people. To my professor and adviser. Dr. Merton Dillon, who meticu lously studied the manuscript, offered suggestions and offered encouragement. To Professors Fisher, Young, Coles and others at Ohio State who have encouraged me and have helped me to understand the true value of historical research. To Miss Barbara RIchburg, who greatly contributed to my happiness and well being while the work was going on. To my mother and father, Mr. and Mrs, Harold Murphy, to whom I shall always be indebted. And, general acknowledgments are due to the library staffs of Ohio State University, Ohio State Library, Ohio Historical Society, Columbus Public Library, and the local office of the Columbus Urban League; and Mrs. Florence Horchow and Mr. Nimrod B. AI I en for the Invaluable service rendered. II VITA February 14, 1936 . , Born - Kinston, North Carolina 1964.......................................... B.A., North Carolina Centrai University, Durham, North Carolina 1964-1965 ............................ Instructor, Grambling College, Grambling, Louisiana 1966.......................................... M.A., North Caroiina Central University, Durham, North Carolina 1965-1967 ........................... -

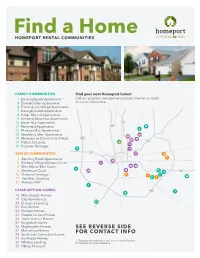

See Reverse Side for Contact Info

FAMILY COMMUNITIES Find your next Homeport home! 1 Bending Brook Apartments1 Call our property management partner (see list on back) 4 Emerald Glen Apartments for more information. 6 Framingham Village Apartments 7 Georges Creek Apartments 8 Indian Mound Apartments 9 Kimberly Meadows Apartments 10 Marsh Run Apartments 11 Parkmead Apartments 12 Pheasant Run Apartments 13 Raspberry Glen Apartments 14 Renaissance Community Village 16 15 Trabue Crossing 23 16 Victorian Heritage1 15 18 SENIOR COMMUNITIES 17 1 Bending Brook Apartments1 2 Eastway Village/Eastway Court 32 3 Elim Manor/Elim Court 5 Fieldstone Court 16 Victorian Heritage1 31 13 21 3 17 Hamilton Crossing 31 Friends VVA2 LEASE-OPTION HOMES 18 Milo Grogan Homes 19 City View Homes 20 Duxberry Landing 21 Elim Estates 22 Fairview Homes 23 Greater Linden Homes 24 Joyce Avenue Homes 25 Kingsford Homes 26 Maplegreen Homes SEE REVERSE SIDE 27 Mariemont Homes 28 South East Columbus Homes FOR CONTACT INFO 29 Southside Homes 1. Property includes both senior and family homes. 30 Whittier Landing 2. Property is in two locations. 32 Hilltop Homes II Call the number listed below for more information, including availability and current rental rates. FAMILY COMMUNITIES BR Phone Management Office Mgmt Partner 1 Bending Brook Apartments 1,2,3 614.875.8482 2584 Augustus Court, Urbancrest, OH 43123 Wallick 4 Emerald Glen Apartments 2,3,4 614.851.1225 930 Regentshire Drive, Columbus, OH 43228 CPO 6 Framingham Village Apartments 3 614.337.1440 3333 Deserette Lane, Columbus, OH 43224 Wallick 7 Georges Creek -

Finding and Using African American Newspapers

Finding and Using African American Newspapers Timothy N. Pinnick [email protected] http://blackcoalminerheritage.net/ INTRODUCTION African American researchers will find black newspapers an extremely valuable part of their search strategy. Although mainstream newspapers should always be consulted, African American newspapers will provide nuggets of information that can be found nowhere else. Although the first African American newspaper was established in 1827, it is in the post Civil War period that the black press experienced tremendous growth. Hundreds of newspapers appeared to quench the thirst for knowledge in the newly freed slaves, and to provide an accurate and positive image of the race. Clint C. Wilson took the incomplete manuscript of the foremost historian of the African American press, Armistead Pride and produced A History of the Black Press in 1997. It is a great source of information on black newspapers. Another worthwhile source can be found online at the public television website of PBS. They produced the documentary film, “The Black Press: Soldiers Without Swords” in 1999, and their website is rich in reference material. http://www.pbs.org/blackpress/index.html VALUE OF BLACK NEWSPAPERS Aside from the most obvious benefit of locating obituaries, researchers can discover: an exact or nearly exact event date (birth, death, or marriage) of an ancestor, therefore enhancing the odds of a successful outcome when the eventual request for the vital record is made. Remember, some places will only search a short span of years in their index, and charge you whether they find the record or not. additional information on the event that will not be found on the vital record. -

C a L L a L O O

C A L L A L O O WHAT WE MEAN WHEN WE SAY ‘CREOLE’ An Interview with Salikoko S. Mufwene by Michael Collins Salikoko S. Mufwene is an internationally renowned theorist of language evolution, language contact, and sociolinguistics, among other subjects. He sat for the following interview on April 7 and April 8, 2003, during a visit he paid to Texas A & M University in College Station to lecture on controversies surrounding Ebonics. Mufwene’s ability to dazzle audiences was just as evident in Texas as it had been in the city-state of Singapore, where I first heard him lecture. His ability was indeed already apparent early in his life in Congo: Robert Chaudenson of the Université d’Aix-en-Provence reports that in 1973 “Mufwene received a License en Philosophie et Lettres (with a major in English Philology) from the National University of Zaire at Lubumbashi (with Highest Honors). The same year he also obtained his Agrégation d’enseignement moyen du degré supérieur (with Honors). Let me comment a bit on the significance of these diplomas, especially for readers who are not familiar with (post)colonial Africa. That the young Salikoko, born in Mbaya-Lareme, would find himself twenty years later in Lubumbashi at the University, with not one but two diplomas, should in itself count as an obvious sign of intellectual excellence for anyone who is in any way familiar with the Congo of that era. Salikoko must have seriously distinguished himself among his peers: at that time, overly limited opportunities and a brutally elitist educational system did entail fierce competition.” For the rest of Chaudenson’s remarks, and for further information on Mufwene, see http://humanities.uchicago.edu/faculty/mufwene/index.html. -

Viewing an Exhibition

Winter 1983 Annual Report 1983 Annual Report 1983 Report of the President Much important material has been added to our library and the many patrons who come to use our collections have grown to the point where space has become John Diehl quite critical. However, collecting, preserving and dissemi- President nating Cincinnati-area history is the very reason for our existence and we're working hard to provide the space needed Nineteen Eight-three has been another banner to function adequately and efficiently. The Board of Trustees year for the Cincinnati Historical Society. The well docu- published a Statement of the Society's Facility Needs in December, mented staff reports on all aspects of our activities, on the to which you responded very helpfully with comments and pages that follow clearly indicate the progress we have made. ideas. I'd like to have been able to reply personally to each Our membership has shown a substantial increase over last of you who wrote, but rest assured that all of your comments year. In addition to the longer roster, there has been a are most welcome and carefully considered. Exciting things heartening up-grading of membership category across-the- are evolving in this area. We'll keep you posted as they board. Our frequent and varied activities throughout the develop. year attracted enthusiastic participation. Our newly designed The steady growth and good health of the quarterly, Queen City Heritage, has been very well received.Society rest on the firm foundation of a dedicated Board We are a much more visible, much more useful factor in of Trustees, a very competent staff and a wonderfully the life of the community.