Our Awardees from 1979 to 2009 WCA

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Revisiting Cyberfeminism

AUTHOR’S COPY | AUTORENEXEMPLAR Revisiting cyberfeminism SUSANNA PAASONEN E-mail: [email protected] Abstract In the early 1990s, cyberfeminism surfaced as an arena for critical analyses of the inter-connections of gender and new technology Ϫ especially so in the context of the internet, which was then emerging as something of a “mass-medium”. Scholars, activists and artists interested in media technol- ogy and its gendered underpinnings formed networks and groups. Conse- quently, they attached altering sets of meaning to the term cyberfeminism that ranged in their take on, and identifications with feminism. Cyberfemi- nist activities began to fade in the early 2000s and the term has since been used by some as synonymous with feminist studies of new media Ϫ yet much is also lost in such a conflation. This article investigates the histories of cyberfeminism from two interconnecting perspectives. First, it addresses the meanings of the prefix “cyber” in cyberfeminism. Second, it asks what kinds of critical and analytical positions cyberfeminist networks, events, projects and publications have entailed. Through these two perspectives, the article addresses the appeal and attraction of cyberfeminism and poses some tentative explanations for its appeal fading and for cyberfeminist activities being channelled into other networks and practiced under dif- ferent names. Keywords: cyberfeminism, gender, new technology, feminism, networks Introduction Generally speaking, cyberfeminism signifies feminist appropriation of information and computer technology (ICT) on a both practical and theoretical level. Critical analysis and rethinking of gendered power rela- tions related to digital technologies has been a mission of scholars but equally Ϫ and vocally Ϫ that of artists and activists, and those working in-between and across such categorizations. -

Oral History Interview with Senga Nengudi, 2013 July 9-11

Oral history interview with Senga Nengudi, 2013 July 9-11 Funding for this interview was provided by Stoddard-Fleischman Fund for the History of Rocky Mountain Area Artists. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a recorded interview with Senga Nengudi on 2013 July 9 and 11. The interview took place in Denver, Colorado, and was conducted by Elissa Auther for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. This interview is part of the Stoddard-Fleischman Fund for the History of Rocky Mountain Area Artists Oral History Project. Senga Nengudi and Elissa Auther have reviewed the transcript. The transcript has been heavily edited. Many of their corrections and emendations appear below in brackets with initials. This transcript has been lightly edited for readability by the Archives of American Art. The reader should bear in mind that they are reading a transcript of spoken, rather than written, prose. Interview ELISSA AUTHER: This is Elissa Auther interviewing Senga Nengudi at the University of Colorado, in Colorado Springs, Colorado, on July 9, 2013, for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Senga, when did you know you wanted to become an artist? SENGA NENGUDI: I'm not, to be honest, sure, because I had two things going on: I wanted to dance and I wanted to do art. My earliest remembrance is in elementary school—I don't know if I was in the fourth or fifth grade—but in class, I had done a clay dog. -

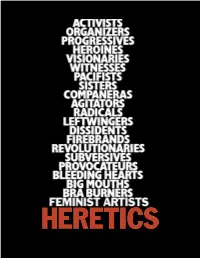

Heretics Proposal.Pdf

A New Feature Film Directed by Joan Braderman Produced by Crescent Diamond OVERVIEW ry in the first person because, in 1975, when we started meeting, I was one of 21 women who THE HERETICS is a feature-length experimental founded it. We did worldwide outreach through documentary film about the Women’s Art Move- the developing channels of the Women’s Move- ment of the 70’s in the USA, specifically, at the ment, commissioning new art and writing by center of the art world at that time, New York women from Chile to Australia. City. We began production in August of 2006 and expect to finish shooting by the end of June One of the three youngest women in the earliest 2007. The finish date is projected for June incarnation of the HERESIES collective, I remem- 2008. ber the tremendous admiration I had for these accomplished women who gathered every week The Women’s Movement is one of the largest in each others’ lofts and apartments. While the political movement in US history. Why then, founding collective oversaw the journal’s mis- are there still so few strong independent films sion and sustained it financially, a series of rela- about the many specific ways it worked? Why tively autonomous collectives of women created are there so few movies of what the world felt every aspect of each individual themed issue. As like to feminists when the Movement was going a result, hundreds of women were part of the strong? In order to represent both that history HERESIES project. We all learned how to do lay- and that charged emotional experience, we out, paste-ups and mechanicals, assembling the are making a film that will focus on one group magazines on the floors and walls of members’ in one segment of the larger living spaces. -

Art Power : Tactiques Artistiques Et Politiques De L’Identité En Californie (1966-1990) Emilie Blanc

Art Power : tactiques artistiques et politiques de l’identité en Californie (1966-1990) Emilie Blanc To cite this version: Emilie Blanc. Art Power : tactiques artistiques et politiques de l’identité en Californie (1966-1990). Art et histoire de l’art. Université Rennes 2, 2017. Français. NNT : 2017REN20040. tel-01677735 HAL Id: tel-01677735 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-01677735 Submitted on 8 Jan 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. THESE / UNIVERSITE RENNES 2 présentée par sous le sceau de l’Université européenne de Bretagne Emilie Blanc pour obtenir le titre de Préparée au sein de l’unité : EA 1279 – Histoire et DOCTEUR DE L’UNIVERSITE RENNES 2 Mention : Histoire et critique des arts critique des arts Ecole doctorale Arts Lettres Langues Thèse soutenue le 15 novembre 2017 Art Power : tactiques devant le jury composé de : Richard CÁNDIDA SMITH artistiques et politiques Professeur, Université de Californie à Berkeley Gildas LE VOGUER de l’identité en Californie Professeur, Université Rennes 2 Caroline ROLLAND-DIAMOND (1966-1990) Professeure, Université Paris Nanterre / rapporteure Evelyne TOUSSAINT Professeure, Université Toulouse - Jean Jaurès / rapporteure Elvan ZABUNYAN Volume 1 Professeure, Université Rennes 2 / Directrice de thèse Giovanna ZAPPERI Professeure, Université François Rabelais - Tours Blanc, Emilie. -

Dear Sister Artist: Activating Feminist Art Letters and Ephemera in the Archive

Article Dear Sister Artist: Activating Feminist Art Letters and Ephemera in the Archive Kathy Carbone ABSTRACT The 1970s Feminist Art movement continues to serve as fertile ground for contemporary feminist inquiry, knowledge sharing, and art practice. The CalArts Feminist Art Program (1971–1975) played an influential role in this movement and today, traces of the Feminist Art Program reside in the CalArts Institute Archives’ Feminist Art Materials Collection. Through a series of short interrelated archives stories, this paper explores some of the ways in which women responded to and engaged the Collection, especially a series of letters, for feminist projects at CalArts and the Women’s Art Library at Goldsmiths, University of London over the period of one year (2017–2018). The paper contemplates the archive as a conduit and locus for current day feminist identifications, meaning- making, exchange, and resistance and argues that activating and sharing—caring for—the archive’s feminist art histories is a crucial thing to be done: it is feminism-in-action that not only keeps this work on the table but it can also give strength and definition to being a feminist and an artist. Carbone, Kathy. “Dear Sister Artist,” in “Radical Empathy in Archival Practice,” eds. Elvia Arroyo- Ramirez, Jasmine Jones, Shannon O’Neill, and Holly Smith. Special issue, Journal of Critical Library and Information Studies 3. ISSN: 2572-1364 INTRODUCTION The 1970s Feminist Art movement continues to serve as fertile ground for contemporary feminist inquiry, knowledge sharing, and art practice. The California Institute of the Arts (CalArts) Feminist Art Program, which ran from 1971 through 1975, played an influential role in this movement and today, traces and remains of this pioneering program reside in the CalArts Institute Archives’ Feminist Art Materials Collection (henceforth the “Collection”). -

Discover Create Share

9TH ANNUAL UNDERGRADUATE SYMPOSIUM DISCOVER CREATE SHARE 9 AM – 4 PM J . L e a om wre yd nce Walkup Sk nau.edu/symposium DOME FLOOR MAP 32 29 26 23 20 17 14 11 8 3 AGE ST ST 34 5 AGE i i 31 28 25 22 19 16 13 10 7 2 FCB D 33 4 C 30 27 24 21 18 15 12 9 6 1 HHS T 118 T CEFNS 121 111 43 COE CAL HONORS 114 GL 117 38 120 113 110 42 46 53 T T 106 108 116 48 R2 R3 37 HONORS 119 112 109 45 52 41 50 CAL FLOOR i i 105 115 FLOOR 107 47 36 R1 51 49 40 44 T 104 35 UC 39 SBS 130 127 124 T 94 87 80 73 66 103 100 97 90 83 76 69 62 59 56 129 126 123 93 86 79 72 65 i 128 125 122 A 102 99 96 89 82 75 68 61 58 55 B 92 85 78 71 64 STAGE 101 98 95 88 81 74 67 60 57 54 STAGE 91 84 77 70 63 i Volunteers CEFNS Room Judges’ Room Skydome East Concourse ADA Section i CHECK-IN / Main Entrance IWP - Video Gaming Symposium EAST CONCOURSE FCB CEFNS GL POSTER DISPLAY The W.A. Franke College of Business College of Engineering, Forestry, and Natural Science Global Learning Program PRESENTATION STAGE KIOSK POSTER DISPLAY BOARD COE SBS HHS College of Education Social and Behavioral Sciences College of Health and Human Services ROUNDTABLE T DISPLAY TABLE D B 1-130 C A CAL HONORS UC College of Arts and Letters University Honors Program University College i INFORMATION MAP NOT TO SCALE Message from the President Dear Students, Faculty Mentors, and Guests, I am privileged to welcome you to NAU’s ninth annual Undergraduate Symposium. -

Patricia Hills Professor Emerita, American and African American Art Department of History of Art & Architecture, Boston University [email protected]

1 Patricia Hills Professor Emerita, American and African American Art Department of History of Art & Architecture, Boston University [email protected] Education Feb. 1973 PhD., Institute of Fine Arts, New York University. Thesis: "The Genre Painting of Eastman Johnson: The Sources and Development of His Style and Themes," (Published by Garland, 1977). Adviser: Professor Robert Goldwater. Jan. 1968 M.A., Hunter College, City University of New York. Thesis: "The Portraits of Thomas Eakins: The Elements of Interpretation." Adviser: Professor Leo Steinberg. June 1957 B.A., Stanford University. Major: Modern European Literature Professional Positions 9/1978 – 7/2014 Department of History of Art & Architecture, Boston University: Acting Chair, Spring 2009; Spring 2012. Chair, 1995-97; Professor 1988-2014; Associate Professor, 1978-88 [retired 2014] Other assignments: Adviser to Graduate Students, Boston University Art Gallery, 2010-2011; Director of Graduate Studies, 1993-94; Director, BU Art Gallery, 1980-89; Director, Museum Studies Program, 1980-91 Affiliated Faculty Member: American and New England Studies Program; African American Studies Program April-July 2013 Terra Foundation Visiting Professor, J. F. Kennedy Institute for North American Studies, Freie Universität, Berlin 9/74 - 7/87 Adjunct Curator, 18th- & 19th-C Art, Whitney Museum of Am. Art, NY 6/81 C. V. Whitney Lectureship, Summer Institute of Western American Studies, Buffalo Bill Historical Center, Cody, Wyoming 9/74 - 8/78 Asso. Prof., Fine Arts/Performing Arts, York College, City University of New York, Queens, and PhD Program in Art History, Graduate Center. 1-6/75 Adjunct Asso. Prof. Grad. School of Arts & Science, Columbia Univ. 1/72-9/74 Asso. -

First Cyberfeminist International

editorial In September 1997 the First Cyberfeminist International Who is OBN and what do they do? took place in the Hybrid Workspace at Documenta X, in The Old Boys Network was founded in Berlin in spring Kassel, Germany. 37 women from 12 countries partici- 1997 by Susanne Ackers, Julianne Pierce, Valentina pated. It was the first big meeting of cyberfeminists Djordjevic, Ellen Nonnenmacher and Cornelia Sollfrank. organized by the Old Boys Network (OBN), the first inter- OBN consists of a core-group of 3-5 women, who take national cyberfeminist organisation. responsibility for administrative and organisational tasks, and a worldwide network of associated members. OBN is dedicated to Cyberfeminism. Although cyber- feminism has not been clearly defined--or perhaps OBN’s concern is to build spaces in which we can because it hasn't--the concept has enormous potential. research, experiment, communicate and act. One Cyberfeminism offers many women--including those example is the infrastructure which is being built by weary of same-old feminism--a new vantage point from OBN. It consists of a cyberfeminist Server (currently which to formulate innovative theory and practice, and under construction), the OBN mailing list and the orga- at the same time, to reflect upon traditional feminist nisation of Real-Life meetings. All this activities have the theory and pratice. purpose to give a contextualized presence to different artistic and political formulations under the umbrella of The concept of Cyberfeminism immediately poses a lot Cyberfeminism. Furthermore we create and use different of questions. The most important ones are: 1. What is kinds of spaces, spaces which are more abstract. -

Dorothy Hood

Dorothy Hood Selected Solo Exhibitions 2020 Earth & Space: Dorothy Hood and Daniel Kayne, Deborah Colton Gallery, Houston, Texas Dorothy Hood: Collage, McClain Gallery, Houston, Texas 2018 Kindred Spirits: Louise Nevelson & Dorothy Hood, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Texas Cosmic Attraction: Dorothy Hood & Don Redman, Deborah Colton Gallery, Houston, Texas 2017 Dorothy Hood: Select Paintings, Deborah Colton Gallery, Houston, Texas 2016 Color of Being/El Color del Ser: Dorothy Hood (1918-2000), Art Museum of South Texas, Corpus Christi, Texas 2003 Dorothy Hood: A Pioneer Modernist, Art Museum of South Texas, Corpus Christi, Texas 1988 Dorothy Hood’s Collages: Connecting Change, Wallace Wentworth Gallery, Washington, DC 1986 Dorothy Hood, Wallace Wentworth Gallery, Washington, DC 1978-79 Dorothy Hood, Meredith Long Contemporary, New York, New York 1978 Paintings, Drawings by Dorothy Hood, McNay Art Museum, San Antonio, Texas 1976 Dorothy Hood, Marienne Friedland Gallery, Toronto, Ontario, Canada 1975 Dorothy Hood, Art Museum of South Texas, Corpus Christi, Texas Dorothy Hood, Michener Galleries, University of Texas at Austin, Texas 1974 Dorothy Hood, New York University, Potsdam, New York Dorothy Hood, Tibor de Nagy Gallery, New York, New York 1972 Dorothy Hood, Everson Museum of Art, Syracuse, New York 1971 Dorothy Hood, Rice University, Houston, Texas 1970 Dorothy Hood: Recent Paintings, Contemporary Arts Museum, Houston, Texas 1965 Dorothy Hood, Witte Museum, San Antonio 1963 Dorothy Hood, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Texas 1961 Dorothy -

NINA YANKOWITZ , Media Artist , N.Y.C

NINA YANKOWITZ , media artist , N.Y.C. www.nyartprojects.com SELETED MUSUEM INSTALLATIONS 2009 The Third Woman interactive film collaboration,Kusthalle Vienna 2009 Crossings Interactive Installation Thess. Biennale Greece Projections, CD Yankowitz&Holden, Dia Center for Book Arts, NYC 2009 Katowice Academy of Art Museum, Poland TheThird Woman Video Tease, Karsplatz Ubahn, project space Vienna 2005 Guild Hall Art Museum, East Hampton, NY Voices of The Eye & Scenario Sounds, distributed by Printed Matter N.Y. 1990 Katonah Museum of Art, The Technological Muse Collaborative Global New Media Team/Public Art Installation Projects, 2008- 2009 1996 The Bass Museum, Miami, Florida PUBLIC PROJECTS 1987 Snug Harbor Museum, Staten Island, N.Yl 1985 Berkshire Museum, Pittsfield, MA Tile project Kanoria Centre for Arts, Ahmedabad, India 2008 1981 Maryland Museum of Fine Arts, Baltimore, MD 1973 Whitney Museum of American Art, NY, Biennia 1973 Brockton Museum, Boston, MA 1972 Larry Aldrich Museum, Ridgefield, Conn. Works on paper 1972 Kunsthaus, Hamburg, Germany, American Women Artists 1972 The Newark Museum, Newark, New Jersey 1972 Indianapolis Museum of Contemporary Art 1972 The Art Institute of Chicago, "American Artists Today" 1972 Suffolk Museum, Stonybrook, NY 1971 Akron Museum of Art, Akron, OH 1970 Museum of Modern Art, NY 1970 Larry Aldrich Museum, Ridgefield, Conn. "Highlights" 1970 Trinity College Museum, Hartford, Conn. ONE PERSON EXHIBITIONS 2005 Kiosk.Edu. Guild Hall Museum, The Garden, E. Hampton, New York 1998 Art In General, NYC. "Scale -

The Native American Fine Art Movement: a Resource Guide by Margaret Archuleta Michelle Meyers Susan Shaffer Nahmias Jo Ann Woodsum Jonathan Yorba

2301 North Central Avenue, Phoenix, Arizona 85004-1323 www.heard.org The Native American Fine Art Movement: A Resource Guide By Margaret Archuleta Michelle Meyers Susan Shaffer Nahmias Jo Ann Woodsum Jonathan Yorba HEARD MUSEUM PHOENIX, ARIZONA ©1994 Development of this resource guide was funded by the Nathan Cummings Foundation. This resource guide focuses on painting and sculpture produced by Native Americans in the continental United States since 1900. The emphasis on artists from the Southwest and Oklahoma is an indication of the importance of those regions to the on-going development of Native American art in this century and the reality of academic study. TABLE OF CONTENTS ● Acknowledgements and Credits ● A Note to Educators ● Introduction ● Chapter One: Early Narrative Genre Painting ● Chapter Two: San Ildefonso Watercolor Movement ● Chapter Three: Painting in the Southwest: "The Studio" ● Chapter Four: Native American Art in Oklahoma: The Kiowa and Bacone Artists ● Chapter Five: Five Civilized Tribes ● Chapter Six: Recent Narrative Genre Painting ● Chapter Seven: New Indian Painting ● Chapter Eight: Recent Native American Art ● Conclusion ● Native American History Timeline ● Key Points ● Review and Study Questions ● Discussion Questions and Activities ● Glossary of Art History Terms ● Annotated Suggested Reading ● Illustrations ● Looking at the Artworks: Points to Highlight or Recall Acknowledgements and Credits Authors: Margaret Archuleta Michelle Meyers Susan Shaffer Nahmias Jo Ann Woodsum Jonathan Yorba Special thanks to: Ann Marshall, Director of Research Lisa MacCollum, Exhibits and Graphics Coordinator Angelina Holmes, Curatorial Administrative Assistant Tatiana Slock, Intern Carrie Heinonen, Research Associate Funding for development provided by the Nathan Cummings Foundation. Copyright Notice All artworks reproduced with permission. -

Native American Painters and Sculptors in the Twentieth Century, 1991

BILLIE JANE BAGULEY LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES HEARD MUSEUM 2301 N. Central Avenue ▪ Phoenix AZ 85004 ▪ 602-252-8840 www.heard.org Shared Visions: Native American Painters and Sculptors in the Twentieth Century, 1991 RC 10 Shared Visions: Native American Painters and Sculptors in the Twentieth Century 2 Call Number: RC 10 Extent: Approximately 3 linear feet; copy photography, exhibition and publication records. Processed by: Richard Pearce-Moses, 1994-1995; revised by LaRee Bates, 2002. Revised, descriptions added and summary of contents added by Craig Swick, November 2009. Revised, descriptions added by Dwight Lanmon, November 2018. Provenance: Collection was assembled by the curatorial department of the Heard Museum. Arrangement: Arrangement imposed by archivist and curators. Copyright and Permissions: Copyright to the works of art is held by the artist, their heirs, assignees, or legatees. Copyright to the copy photography and records created by Heard Museum staff is held by the Heard Museum. Requests to reproduce, publish, or exhibit a photograph of an art works requires permissions of the artist and the museum. In all cases, the patron agrees to hold the Heard Museum harmless and indemnify the museum for any and all claims arising from use of the reproductions. Restrictions: Patrons must obtain written permission to reproduce or publish photographs of the Heard Museum’s holdings. Images must be reproduced in their entirety; they may not be cropped, overprinted, printed on colored stock, or bleed off the page. The Heard Museum reserves the right to examine proofs and captions for accuracy and sensitivity prior to publication with the right to revise, if necessary.