The Sand-Dunes of the Libyan Desert. Their Origin, Form, And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Middle East Today: Political Map

The Middle East Today: Political Map 19 17 18 11--> 7 6 1 13 8--> 9 <--10 2 12 5 16 20 14 21 Middle East? OR Near East? OR Southwest Asia? OR….? Bodies of Water Black Sea Dardanelles Strait Atlantic Tigris Ocean EuphratesRiver Jordan River River Suez Canal Strait of Hormuz Nile Gulf of River Oman Arabian Sea Gulf of Aden Indian Ocean The Mighty Nile River: “Longest River in the World” Egypt: The “Gift of the Nile” Nile Delta Annual Nile Flooding 95% of the Egyptian people live on 5% of the land! Aswan High Dam, Egypt Hydroelectric Power Plant Suez Canal Completed by the British in 1869 Population Patterns Migrations, claims to ancestral homes, and boundary disputes have influenced population in the eastern Mediterranean. • The people: – About 7.1 million people in this region are Israelis living in Israel. Population Patterns (cont.) – The majority of people live along• Densitycoastal andplains distribution: This area has some of the highest population densities in Southwest Asia. – This subregion is predominantly urban— more than 75% of the people in Israel, Jordan, and Lebanon live in cities. – Just over 50% in Syria and Palestine live in cities. History and Government The eastern Mediterranean is home to three of the world’s major religions that have shaped politics and culture there for centuries. What Are they? • Christian • Islam • Judaism Population Patterns (cont.) – Tensions between Arabs and Jews resulted in six wars over the past 70 years. – 80% of the Israelis are Jewish. – ars. Population Patterns for this region of Ancient Persia Ethnic diversity and the Muslim religion have profoundly shaped the population of the Northeast subregion. -

Page 1 of 7 Location the Nation of Libya Is Located in North Africa And

Libya Location The nation of Libya is located in North Africa and covers approximately one million seven hundred fifty square kilometers, which is slightly larger than the United State’s Alaska. It is one of the largest countries in Africa. Libya lies in the geographic coordinates 25°N and 17°E. It is bordered in the north by the Mediterranean Sea and by Niger and Chad in the south. Libya’s western border connects to Algeria and Tunisia, and connects to Egypt and Sudan in the east. Geography The highest point in Libya is the Bikku Bitti, also known as Bette Peak, which stands at seven thousand four hundred and thirty eight feet at its highest point. It is located in the Tibesti Mountains in southern Libya near the Chadian border. The Sahara, an immense North African desert, covers most of Libya. Much of the country’s land consists of barren, rock-strewn plains and sand sea, with flat to underlying plains, plateaus, and depressions. Two small areas of hills ascend in the northwest and northeast, and the Tibesti mountains rise near the southern border. There are no permanent rivers or streams in Libya. The coastline is sunken near the center by the Gulf of Sidra, where barren desert reaches the Mediterranean Sea. Libya is divided into three natural regions. The first and largest, to the east of the Gulf of Sidra, is Cyrenaica, which occupies the plateau of Jabal al Akhdar. The majority of the area of Cyrenaica is covered with sand dunes, especially along the border with Egypt. -

Very High-Temperature Impact Melt Products As Evidence For

Very high-temperature impact melt products PNAS PLUS as evidence for cosmic airbursts and impacts 12,900 years ago Ted E. Buncha,1, Robert E. Hermesb, Andrew M.T. Moorec, Douglas J. Kennettd, James C. Weavere, James H. Wittkea, Paul S. DeCarlif, James L. Bischoffg, Gordon C. Hillmanh, George A. Howardi, David R. Kimbelj, Gunther Kletetschkak,l, Carl P. Lipom, Sachiko Sakaim, Zsolt Revayn, Allen Westo, Richard B. Firestonep, and James P. Kennettq aGeology Program, School of Earth Science and Environmental Sustainability, Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff, AZ 86011; bLos Alamos National Laboratory (retired), Los Alamos, NM 87545; cCollege of Liberal Arts, Rochester Institute of Technology, Rochester, NY 14623; dDepartment of Anthropology, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802; eWyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA 02138; fSRI International, Menlo Park, CA 94025; gUS Geological Survey, Menlo Park, CA 94025; hInstitute of Archaeology, University College London, London, United Kingdom; iRestoration Systems, LLC, Raleigh, NC 27604; jKimstar Research, Fayetteville, NC 28312; kFaculty of Science, Charles University in Prague, and lInstitute of Geology, Czech Academy of Science of the Czech Republic, v.v.i., Prague, Czech Republic; mInstitute for Integrated Research in Materials, Environments, and Society (IIRMES), California State University, Long Beach, CA 90840; nForschungsneutronenquelle Heinz Maier-Leibnitz (FRM II), Technische Universität München, Munich, Germany; oGeoScience Consulting, Dewey, AZ 86327; pLawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Berkeley, CA 94720; and qDepartment of Earth Science and Marine Science Instititute, University of California, Santa Barbara, CA 93106 Edited by* Steven M. Stanley, University of Hawaii, Honolulu, HI, and approved April 30, 2012 (received for review March 19, 2012) It has been proposed that fragments of an asteroid or comet (2). -

Climatic Changes M the Arid Zones of Africa During Early to Mid-Holocene Times

Reprinted from the RoYAL 11ETEOROLOGICAL SOCIETY PROCEEDINGS OF THE INTERNATIONAL SYMPOSIUM ON WORLD CLUvIATE FROM 8000 To O s.c. 551.583.3 (6) Climatic changes m the arid zones of Africa during early to mid-Holocene times By KARL W. BUTZER Department of Geography, University of Wisc-onsin, Madison* SUMMARY The arid zones of Africa, while always subject to comparatively dry climate during more recent geological times, have nonetheless experienced a succession of moister or drier oscillations during the Pleistocene and Holocene, The various classes of palaeoclimatic evidence (archaeological, geological, pedological, palynolo gical, palaeontological) are reviewed briefly. Despite considerable advances during the last decade, the present status of information is still highly unsatisfactory, due in part to the limited numbers of workers in the field, and in part to the difficulties of exact dating and reliable correlation. In the case_ of the Sahara the available evidence suggests that a hyper-arid oscillation c, 2350-870 s.c. was preceded by a moister sub-pluvial period c. 5500-2350 s.c., possibly interrupted by one or more dry spells. There is some further evidence in favour of moister conditions during the 7th millennium while conditions may have been hyper-arid a millennium earlier. None of these changes in precipitation or effective moisture can be quantitatively defined, and there is no evidence concerning temperature conditions. A palaeoclimatic outline is not yet possible for the remain ing arid zones of Africa, no matter how tentative. 1. INTRODUCTION The Sahara and the Kalahari-Namib deserts of Africa have experienced comparatively dry climates throughout most of geological history. -

Confirmation of a Meteoritic Component in Libyan Desert Glass from Osmium Isotope Data

63rd Annual Meteoritical Society Meeting 5253.pdf CONFIRMATION OF A METEORITIC COMPONENT IN LIBYAN DESERT GLASS FROM OSMIUM ISOTOPE DATA. C. Koeberl, Institute of Geochemistry, University of Vienna, Althanstrasse 14, A-1090 Vienna, Austria ([email protected]). Libyan Desert Glass (LDG) is an enigmatic chondritic component [e.g., 1]. To confirm the type of natural glass, which occurs in a 6500 presence of a meteoritic component, the Os km² strewn field located between sand dunes of isotopic composition of dark LDG layers was the southwestern corner of the Great Sand Sea analyzed by NTIMS (see [5] for details and in western Egypt. The glass is very silica-rich at background). The analyses were difficult, about 96.5–99 wt% SiO2, and shows a limited because of the small size of the brown schlieren variation in major and trace element and problems to isolate mainly schlieren-rich abundances (e.g., [1]). Some cristobalite material. The best sample, with the highest Os inclusions occur, but otherwise the LDG, content, was found to contain 0.626 ppb Os, which has an age of about 28 Ma, is perfectly 0.0237 ppb Re, and a 188Os/187Os-isotopic ratio glassy. Although the origin of LDG is still of 0.1276. Samples with lower Os abundances debated by some workers, an origin by impact have higher isotopic ratios. Crustal Sr and Nd seems most likely. There are, however, some isotopic values exclude a significant mantle differences to "classical" impact glasses, which component; thus, the Os abundances and occur in most cases directly at or within an isotopic values conform the presence of a impact crater. -

African Rain Forest

A Satellite View Bodies Mediterranean Sea Of Water • Most of the rivers in Nile River Africa south of the L. Chad--> Sahara are hard to navigate from source to L. Albert--> mouth. L. Victoria • Droughts and a dry L. Tanganyika-> Indian Ocean climate have contributed to the shrinking size of Atlantic Ocean Lake Chad. Zambezi River • Lake Victoria the largest Limpopo River lake in Africa, is located Orange River between the eastern and western branches of the Pacific Ocean Great Rift Valley. Bodies Mediterranean Sea Of Water • The course of the Nile River Zambezi River to the L. Chad--> sea is interrupted by Victoria Falls on the L. Albert--> border of Zambia and Zimbabwe. L. Victoria L. Tanganyika-> Indian Ocean • Does Africa have plenty of water? Atlantic Ocean Zambezi River Limpopo River Orange River Pacific Ocean Soil and water • Why are soils in the tropical wet areas of Africa not very fertile? • Heavy rains leach, or dissolve and carry away, nutrients from the soil. African Rain Forest # Annual rainfall of up to 17 ft. # Rapid decomposition (very humid). # Covers 37 countries. # 15% of the land surface of Africa. The Congo River Basin # Covers 12% of the continent. # Extends over 9 countries. # 2,720 miles long. # 99% of the country of Zaire is in the Congo River basin. # @Realsworth The Niger River Basin # Covers 7.5% of the continent. # Extends over 10 countries. # 2,600 miles long. Hydroelectric Power Mountains & Peaks • Highest point in Africa is Mt. Kiliminjaro. Δ Mt. Kenya • Lake Assal is a saline Δ Mt. Kilimanjaro lake which lies 155 m (509 ft) below sea level is the lowest point on land in Africa and the third lowest land depression on Earth after the Dead Sea and Sea of Galilee. -

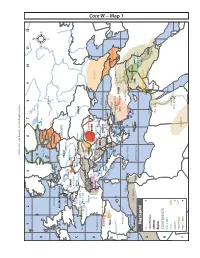

Core W—Map 1

©2013 by Sonlight Curriculum, Ltd. All rights reserved. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Baltic Shore St. Petersburg (Leningrad) A Neva River Baltic Sea ESTONIA LATVIA Moscow DENMARK Baltic States Gilleleje Helsingr North Sea Kolding Copenhagen LITHUANIA B HOLLAND/NETHERLANDS Gdynia BRITAIN EUROPE Witte Verden POLAND Alkmaar West Berlin Warsaw Amsterdam Amersfoort Brunswick GERMANY Oder River Calais Saxony BELGIUM Frankfurt Cambrai Prague Krakow C Crécy Mainz Elbe River Worms Rhine River Carpathian Mountains UKRAINE Paris Marne Brno Brest Normandy Seine River Vienna Hungarian Plain Tisza River Orléans Basel Oberammergau Swiss Alps Budapest Cluj Chalon Faido HUNGARY Transylvania W— Core Geneva Mendrisio Como Trieste Zagreb ROMANIA D Venice Crimea Lombardy Belgrade Danube River Caucasus Burtigala(Bordeaux) Genoa Florence Ravenna Alps Bucharest Sarajevo Rubicon River San Marino SERBIA Black Sea Pyrenees Mountains Tiber River BULGARIA Navarre Soa Stara Zagora Elba ITALY MONTENEGRO Plovdiv Rhodope Mountains Rome MACEDONIA SPAIN Aragon Adriatic Sea Tirana Map 1 E Pompeii ALBANIA Serrai Philippi Constantinople Salerno Brindisi Transcaucasia Thebe Hellespont (Dardanelles) Mount Ararat GREECE Bay of Salamis Scyros TURKEY Thermopylae Lydia Phrygia Assyria Córdoba (Cordova) Ithaca Athens SICILY Çatal Hüyük Hippo Zama Carthage Siracusa (Syracuse) Sparta Nineveh F Cadiz Pillars of Heracles Knossos Lycia Mesopotamia Strait of Gibraltar Atlas Mountains Tigris River TUNISIA Mediterranean Sea Crete SYRIA Euphrates River Map Legend Byblos Northern Kingdom Baghdad Cities ISRAEL G Rosetta Southern Kingdom CHALDEA States/Provinces Alexandria Judea Ur COUNTRIES Memphis Regions H CONTINENTS Bodies of Water Red Sea Deserts Abydos Thebes Mountain Hermonthis Mountain Range Libyan Desert I Points of Interest ©2013 by Sonlight Curriculum, Ltd. -

Assessment Reports on Emerging Ecological Issues in Central Asia

ASSESSMENT REPORTS ON EMERGING ECOLOGICAL ISSUES IN CENTRAL ASIA Ashgabat Foreword In December 2006, five Central Asian countries established the Environment Convention as an important initiative for regional co- operation among the member states on sustainable development. The implementation of the Convention requires regular assessment of the state of the environment with a focus on emerging environ- mental issues. The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) is mandated to regularly assess and monitor major environmental challenges and trends. The rapid socio-economic growth coupled with increase in intensity and frequency of natural disasters have brought many challenging emerging issues to the forefront. The emerging environmental issues are a threat to food security, water security, energy security and sustainable development. This assessment report on the emerging environmental issues in Central Asia is timely and meaningful to the Central Asian region. The report, the first of its kind in Central Asia, identifies key emerging en- vironmental issues in Central Asia – Atmospheric Brown Cloud, Dust Storms, Glacial Melt, Integrated Chemical Management and the Use of Alternative Energy Resources. These issues have been ana- lyzed based on sound science by various experts, including scientists, academics and civil society representatives, to determine their impact on environment and population. Based on the analysis the report identifies the gaps in the existing system to address the emerging environmental issues and provide clear recommendations to fill the gaps. I believe that this report will bring emerging environmental issues to the attention of different stake- holders including the general public. This report will also provide a sound basis for decision makers in Central Asian countries in addressing the emerging environmental issues at the policy level. -

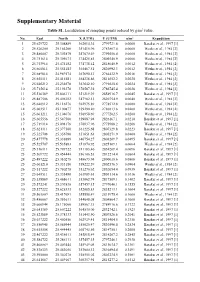

Fluvial Transport Model from Spatial Distribution Analysis Of

Supplementary Material Table S1. Localization of sampling points ordered by g/m2 value. No. East North X (UTM) Y (UTM) g/m2 Expedition 1 25.629722 25.308889 362014.34 2799721.8 0.0000 Barakat et al., 1997 [1] 2 25.526200 25.164200 351415.96 2783867.0 0.0000 Weeks et al., 1984 [2] 3 25.486807 25.303879 347670.49 2799456.4 0.0000 Weeks et al., 1984 [2] 4 25.751614 25.395673 374425.85 2809348.9 0.0008 Weeks et al., 1984 [2] 5 25.753914 25.474182 374738.42 2818040.9 0.0012 Weeks et al., 1984 [2] 6 25.660811 25.554183 365467.51 2826992.3 0.0012 Weeks et al., 1984 [2] 7 25.689014 24.989574 367690.13 2764432.9 0.0016 Weeks et al., 1984 [2] 8 25.650111 25.415581 364236.86 2811652.2 0.0020 Weeks et al., 1984 [2] 9 25.646212 25.234678 363642.10 2791620.6 0.0024 Weeks et al., 1984 [2] 10 25.715614 25.191278 370587.38 2786745.4 0.0028 Weeks et al., 1984 [2] 11 25.516389 25.806111 351219.29 2854916.7 0.0045 Barakat et al., 1997 [1] 12 25.487506 25.496182 347982.12 2820754.9 0.0040 Weeks et al., 1984 [2] 13 25.640912 25.116276 362975.89 2778512.8 0.0080 Weeks et al., 1984 [2] 14 25.603511 25.190877 359290.20 2786813.6 0.0200 Weeks et al., 1984 [2] 15 25.601211 25.104076 358958.69 2777202.5 0.0200 Weeks et al., 1984 [2] 16 25.605556 25.547500 359887.94 2826167.1 0.0210 Barakat et al., 1997 [1] 17 25.719114 25.094176 370837.96 2775988.2 0.0208 Weeks et al., 1984 [2] 18 25.621111 25.377500 361225.68 2807329.8 0.0223 Barakat et al., 1997 [1] 19 25.525708 25.356780 351651.63 2805271.9 0.0400 Weeks et al., 1984 [2] 20 25.477778 25.338889 346754.27 2803209.7 -

A 2003 Expedition Into the Libyan Desert Glass Strewn Field, Great Sand Sea, Western Egypt

Large Meteorite Impacts (2003) 4079.pdf A 2003 EXPEDITION INTO THE LIBYAN DESERT GLASS STREWN FIELD, GREAT SAND SEA, WESTERN EGYPT. Christian Koeberl1, Michael R. Rampino2, Dona A. Jalufka1, and Deborah H. Winiarski2. 1Department of Geological Sciences, University of Vienna, Althanstrasse 14, Vienna, A-1090, Austria, (chris- [email protected]), 2Earth & Environmental Science Program, New York University, 100 Washington Square East, New York, NY 10003, USA ([email protected]). Introduction: Libyan Desert Glass (LDG) is an partly digested mineral phases, lechatelierite (a high- enigmatic type of natural glass that is found in an area temperature mineral melt of quartz), and baddeleyite, a with an extension of several thousand square kilometers. high-temperature breakdown product of zircon. Literature values on the extent vary between about 2000 The rare earth element abundance patterns are and 6500 km². This area, or strewn field, is located indicative of a sedimentary precursor rock, and the trace between sand dunes of the southwestern corner of the element abundances and ratios are in agreement with an Great Sand Sea in western Egypt, near the border to upper crustal source. There is a similarity between LDG Libya. Therefore, the name "Libyan" Desert Glass is not major and trace element abundances and Sr and Nd entirely correct, given today’s geographical boundaries, isotopic compositions and the respective values for rocks but refers to the traditional name of the desert. P.A. from the B.P. and Oasis impact structures in eastern Clayton was the first to travel the region in the early Libya, but lack of age information for the two Libyan 1930s and to collect glass samples that were used to structures precludes a definitive conclusion. -

Prof. Dr. Olaf Bubenzer Selected Publications/Ausgewählte

Prof. Dr. Olaf Bubenzer - Quaternary Research & - Quartärforschung & Applied Geomorphology Angewandte Geomorphologie - African Research Unit - Abteilung für Afrikaforschung Institute of Geography Geographisches Institut University of Cologne Universität zu Köln Albertus-Magnus-Platz Albertus-Magnus-Platz 50923 Cologne/Köln 50923 Köln Germany Deutschland Phone +49 (0) 221 470 3966 Tel +49 (0) 221 470 3966 FAX +49 (0) 221 470 5124 FAX +49 (0) 221 470 5124 Mail [email protected] Mail [email protected] Selected Publications/Ausgewählte Publikationen BUBENZER, O., EMBABI, N. & ASHOUR, M. (in review): Sand seas and dune fields in Egypt. – Quaternary International. REINL, C., FRICKE, K. & BUBENZER, O. (in review): Urumqi 1886 – 2020: From a Frontier-City to an Industrial Centre of Central Asia. – Erdkunde. BUBENZER, O. & BOLTEN, A. (accepted): Top Down: New Satellite Data and Ground Truth Data as Base for a Reconstruction of Ancient Caravan Routes – Examples from the Western Desert of Egypt. In: FÖRSTER, F. & RIEMER, H. (eds.): Desert Road Archaeology, Cologne. BUBENZER, O. & BRUNOTTE, E. (in press): Der natürliche Rahmen Köln – Die Kölner Bucht in einem geomorphologisch-geoökologischen Profil. In: GELHAR, M., KRAAS, F., SCHWEIZER, G. & ZEHNER, K. (eds.): Köln. Ein Geographischer Exkursionsführer. 2. veränderte u. aktualisierte Aufl. – Kölner Geographische Arbeiten. KINDERMANN, K., BUBENZER, O. & VAN PEER, PH. (2013): Geo-archaeological research on the Late Pleistocene of the Egyptian Eastern Desert – recent threats to the Sodmein Cave. – Antiquity 377: project galley. LÖW, F., NAVRATIL, P., KOTTE, K., SCHÖLER, H.F. & BUBENZER, O. (2013): Remote sensing based monitoring of landscape change in the desiccated seabed of the Aral Sea – a growing source for dust storms in Middle Asia. -

The Route Most Traveled: the Afar Salt Trail, North Ethiopia1

Volumen 51, N° 1, 2019. Páginas Páginas 95-110 Chungara Revista de Antropología Chilena THE ROUTE MOST TRAVELED: THE AFAR SALT TRAIL, NORTH ETHIOPIA1 LA RUTA MÁS TRANSITADA: EL SENDERO DE LA SAL DE AFAR, NORTE DE ETIOPÍA Helina S. Woldekiros2 In Africa and elsewhere, scholars have demonstrated that early social, political, and economic structures were shaped by salt production, distribution, and long-distance trade in areas where salt was a critical resource. However, despite salt’s significant role in developing these structures, archaeological studies of the salt trade have focused almost exclusively on artifacts and historical text references. As a result, data on the diverse and complex routes through which this important commodity has traveled and the nature of its transportation are lacking. This paper examines evidence of ancient Aksumite (400 BC–900 AD) salt trade and exchange from the lowland Ethiopian deserts to the North Ethiopian and Eritrean highlands, drawing on recent ethnoarchaeological and archaeological fieldwork conducted in the Danakil Desert and Aksumite towns. The data reveal that the Afar salt trail passes through diverse regional ecozones, highland trader towns, and foothill towns, via several highland routes and one major lowland route. The study shows that caravaners followed the least costly path on the highland portion of the route, with ideal slopes for pack travel and plentiful water sources. The study also describes ancient caravan campsites dating to ca. 5th century CE and shows that participants differed in religion and identity. Key words: Salt caravan, Aksumite trade, Africa, ethnoarchaeology. En África como en otros lugares, los investigadores han demostrado que estructuras políticas, sociales y económicas tempranas fueron moldeadas por la producción de sal así como por su distribución y comercio de larga distancia en áreas donde la sal era un recurso crítico.