Criminal Prosecutions in Western Australia: a View from the Nineteenth Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2011 Administering Justice for the Community for 150 Years

The Supreme Court of Western Australia 1861 - 2011 Administering Justice for the Community for 150 years by The Honourable Wayne Martin Chief Justice of Western Australia Ceremonial Sitting - Court No 1 17 June 2011 Ceremonial Sitting - Administering Justice for the Community for 150 Years The court sits today to commemorate the 150th anniversary of the creation of the court. We do so one day prematurely, as the ordinance creating the court was promulgated on 18 June 1861, but today is the closest sitting day to the anniversary, which will be marked by a dinner to be held at Government House tomorrow evening. Welcome I would particularly like to welcome our many distinguished guests, the Rt Hon Dame Sian Elias GNZM, Chief Justice of New Zealand, the Hon Terry Higgins AO, Chief Justice of the ACT, the Hon Justice Geoffrey Nettle representing the Supreme Court of Victoria, the Hon Justice Roslyn Atkinson representing the Supreme Court of Queensland, Mr Malcolm McCusker AO, the Governor Designate, the Hon Justice Stephen Thackray, Chief Judge of the Family Court of WA, His Honour Judge Peter Martino, Chief Judge of the District Court, President Denis Reynolds of the Children's Court, the Hon Justice Neil McKerracher of the Federal Court of Australia and many other distinguished guests too numerous to mention. The Chief Justice of Australia, the Hon Robert French AC had planned to join us, but those plans have been thwarted by a cloud of volcanic ash. We are, however, very pleased that Her Honour Val French is able to join us. I should also mention that the Chief Justice of New South Wales, the Hon Tom Bathurst, is unable to be present this afternoon, but will be attending the commemorative dinner to be held tomorrow evening. -

Common Law Pleadings in New South Wales

COMMON LAW PLEADINGS IN NEW SOUTH WALES AND HOW THEY GOT HERE John P. Bryson * Advantages and disadvantages para 1 Practice before 1972 para 17 The Texts para 21 Pleadings after the Reform legislation para 26 The system in England before Reform legislation para 63 Recurring difficulties before Reform legislation para 81 The Process of Change in England para 98 How the system reached New South Wales para 103 Procedure in the Court in Banco para 121 Court and Chambers para 124 Diverse Statutes and Procedures para 126 Every-day workings of the system of pleading para 127 Anachronism and Catastrophe para 132 The End para 137 Advantages and disadvantages 1. There can have been few stranger things in the legal history of New South Wales than the continuation until 30 June 1972 of the system of Common Law pleading, discarded in England in 1875 after evolving planlessly over the previous seven Centuries. The Judicature System in England was the culmination of half a century of reform in the procedures and constitution of the courts, prominent among rapid transformations in British economy, politics, industry and society in the Nineteenth Century. With the clamant warning of revolutions in France, the end of the all- engrossing Napoleonic Wars and the enhanced representative character of the House of Commons, the British Parliament and community shook themselves and changed the institutions of society; lest a worse thing happen. As well as reforming itself, the British Parliament in a few decades radically reformed the law relating to the procedure and organisation of the courts, the Established Church, municipal corporations and local government, lower courts, Magistrates and police, 1 corporations and economic organisations, the Army, Public Education, Universities and many other things. -

Fusion – Fission – Fusion Pre-Judicature Equity Jurisdiction In

M Leeming, “Fusion-Fission-Fusion: Pre-Judicature Equity Jurisdiction in New South Wales 1824- 1972 in J Goldberg et al (eds), Equity and Law: Fusion and Fission (Cambridge UP 2019), 118-143. Fusion – Fission – Fusion Pre-Judicature Equity Jurisdiction in New South Wales 1824 - 1972 Mark Leeming* Introduction Here is a vivid account of the pre-Judicature Act system which prevailed in New South Wales at the end of the nineteenth century and its origins: To the litigant who sought damages before an Equity Judge, a grant of Probate before a Divorce Judge or an injunction before a Common Law Judge, there could be no remedy. He had come to the wrong Court, so it was said. He might well have enquired on what historical basis he could thus be denied justice. It cannot be questioned that the Court required specialization to function properly and that a case obviously falling within one jurisdiction ought not to be heard by a Judge sitting in another jurisdiction. Yet from this the fallacious extension was made that a Judge sitting in one jurisdiction could not in any circumstances hear a case which ought to have originated in another jurisdiction.1 The words are those of the distinguished Australian legal historian J.M. Bennett. There is no doubt that the jurisdictions at common law and in equity came to be treated in many respects as if they were separate courts, despite the failure of sustained efforts to create a separate equity court; despite it being clear that there was a single Supreme Court of New South Wales with full jurisdiction at common law and in equity; and despite efforts by its first Chief Justice, Sir Francis Forbes, in the opposite direction. -

Introduction to Statutory Interpretation

1 1 INTRODUCTION TO STATUTORY INTERPRETATION We live in an exciting time of transition. The great commons of the common law are being engulfed by a tsunami of legislation. 1 1 K Mason, ‘The Intent of Legislators: How Judges Discern It and What They Do if They Find It’, in Statutory Interpretation: Principles and Pragmatism for a New Age ( Judicial Commission of New South Wales, 2007) 33 at 44. Oxford University Press Sample Chapter 01_SAN_SI_2e_04577_TXT_SI.indd 1 18/04/2016 4:45 pm 2 STATUTORY INTERPRETATION Legislation is the predominant source of law applied by judges in the common law world today. This is because, even though the doctrine of precedent allows for the development of law by judges through cases, most areas of law are now set down in statutes, and cases primarily concerning their interpretation. Accordingly, advanced skills in statutory interpretation are essential for all legally trained people. No longer is it adequate to have a vague memory of approaches to interpretation learned during first- year law. Through legislation, Parliament communicates, to individuals and corporations alike, what it expects them to do and refrain from doing, and what procedures they must follow to effect certain outcomes. Being able to properly advise clients on the way legislation applies to their professional or personal circumstances can reduce the incidence of litigation, and being able to succinctly advocate for a particular interpretation during a court case can reduce the length, and therefore the cost, of hearings. Statutory interpretation is not just one extra skill for lawyers to have. It is a central, essential skill—an area of law in itself.2 James Spigelman, when he was Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of New South Wales, stated that ‘the law of statutory interpretation has become the most important single aspect of legal practice. -

“A Veritable Augustus”: the Life of John Winthrop Hackett, Newspaper

“A Veritable Augustus”: The Life of John Winthrop Hackett, Newspaper Proprietor, Politician and Philanthropist (1848-1916) by Alexander Collins B.A., Grad.Dip.Loc.Hist., MSc. Presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of Murdoch University March 2007 I declare that this thesis is my own account of my research and contains as its main content work which has not been previously submitted for a degree at any tertiary education institution. ……………………….. Alexander Collins ABSTRACT Irish-born Sir John Winthrop Hackett was a man of restless energy who achieved substantial political authority and social standing by means of the power gained through his editorship and part-ownership of the West Australian newspaper and his position in parliament. He was a man with a mission who intended to be a successful businessman, sought to provide a range of cultural facilities and, finally, was the moving force in establishing a tertiary educational institution for the people of Western Australia. This thesis will argue that whatever Hackett attempted to achieve in Western Australia, his philosophy can be attributed to his Irish Protestant background including his student days at Trinity College Dublin. After arriving in Australia in 1875 and teaching at Trinity College Melbourne until 1882, his ambitions took him to Western Australia where he aspired to be accepted and recognised by the local establishment. He was determined that his achievements would not only be acknowledged by his contemporaries, but also just as importantly be remembered in posterity. After a failed attempt to run a sheep station, he found success as part-owner and editor of the West Australian newspaper. -

Law Reform Committee

LAW REFORM COMMITTEE Jury Service in Victoria FINAL REPORT Volume 3 DECEMBER 1997 PARLIAMENT OF VICTORIA LAW REFORM COMMITTEE Jury Service in Victoria FINAL REPORT VOLUME 3 REPORT ON RESEARCH PROJECTS Ordered to be Printed Melbourne Government Printer December 1997 N° 76 Session 1996–97 COMMITTEE M EMBERS CHAIRMAN Mr Victor Perton, MP DEPUTY CHAIR Mr Neil Cole, MP MEMBERS Mr Florian Andrighetto, MP Hon Carlo Furletti, MLC Hon Monica Gould, MLC Mr Peter Loney, MP Mr Noel Maughan, MP Mr Alister Paterson, MP Mr John Thwaites, MP The Committee's address is — Level 8, 35 Spring Street MELBOURNE VICTORIA 3000 Telephone inquiries — (03) 9651 3644 Facsimile — (03) 9651 3674 Email — [email protected] Internet— http://www.vicnet.net.au/~lawref COMMITTEE S TAFF EXECUTIVE OFFICER and DIRECTOR OF RESEARCH Mr Douglas Trapnell RESEARCH OFFICERS Mr Mark Cowie (until 10 November 1995) Ms Padma Raman (from 3 March 1997) Ms Rebecca Waechter (until 18 November 1997) ADDITIONAL RESEARCH ASSISTANCE Ms Angelene Falk OFFICE MANAGERS Mrs Rhonda MacMahon (until 18 October 1996) Ms Lyn Petersen (from 2 December 1996 to 1 June 1997) Ms Angelica Vergara (from 11 August 1997) CONTENTS Committee Membership ........................................................................................................ iii Committee Staff ......................................................................................................................v Functions of the Committee...................................................................................................xi -

Wendy Jenklns-Beverl Y Farmer White-Leigh Alhson-Ron Twaddle an Examination of Western Paperba K Novels

Short StorIes Wendy Jenklns-Beverl y Farmer WhIte-LeIgh Alhson-Ron Twaddle An ExamInatIon of Western Paperba k Novels Poems by Japanese Women In TranslatIon Westerly Index 1978-1980 University of Western Australia Press FORTHCOMING TITLES AND THIS YEAR'S BEST·SELLERS A History of Dairying in Western Australia, reprint $25.00 Maurice Cullity Aborigines of the West: Their Past and Their Present, reprint $16.95 Ronald M. Berndt and Catherine H. Berndt, editors, Foreword by Paul Hasluck The Beginning: European Discovery and Early Settlement of the Swan River, reprint $13.95 R. T. Appleyard and Toby Manford But Westward Look: Nursing in Western Australia 1829-1979, reprint $15.00 Victoria Hobbs Unfinished Voyages: Western Australian Shipwrecks 1622-1850 $19.95 Graeme Henderson The Short Stories of Marcel Ayme $9.95 Graham Lord Everyman $3.95 Geoffrey Cooper and Christopher Wortham, editors The Letters of William Tanner P. Statham, editor A New History of Western Australia C. T. Stannage, editor Ambitions Fire: The Agricultural Colonization of Pre-Convict Western Australia J. M. R. Cameron A History of the Law in Western Australia and its Development, 1829-1979 Enid Russell, F. M. Robinson and P. W. Nichols, editors Biology of Native Plants J. S. Pate UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA PRESS, Nedlands, W.A. 6009 Telephone 3803181 WESTERLY a quarterly review ISSN 0043-342x EDITORS: Bruce Bennett and Peter Cowan EDITORIAL ADVISORS: Margot Luke, Susan Kobulniczky, Fay Zwicky CONSULTANTS: Brian Dibble, Anand Haridas Westerly is published quarterly by the English Department, University of Western Australia, with assistance from the Literature Board of the Australia Council and the Western Australian Literary Fund. -

Crown and Sword: Executive Power and the Use of Force by The

CROWN AND SWORD EXECUTIVE POWER AND THE USE OF FORCE BY THE AUSTRALIAN DEFENCE FORCE CROWN AND SWORD EXECUTIVE POWER AND THE USE OF FORCE BY THE AUSTRALIAN DEFENCE FORCE CAMERON MOORE Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Creator: Moore, Cameron, author. Title: Crown and sword : executive power and the use of force by the Australian Defence Force / Cameron Moore. ISBN: 9781760461553 (paperback) 9781760461560 (ebook) Subjects: Australia. Department of Defence. Executive power--Australia. Internal security--Australia. Australia--Armed Forces. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU Press. Cover photographs by Søren Niedziella flic.kr/p/ ahroZv and Kurtis Garbutt flic.kr/p/9krqeu. This edition © 2017 ANU Press Contents Prefatory Notes . vii List of Maps . ix Introduction . 1 1 . What is Executive Power? . 7 2 . The Australian Defence Force within the Executive . 79 3 . Martial Law . 129 4 . Internal Security . 165 5 . War . 205 6 . External Security . 253 Conclusion: What are the Limits? . 307 Bibliography . 313 Prefatory Notes Acknowledgement I would like to acknowledge the tremendous and unflagging support of my family and friends, my supervisors and my colleagues in the writing of this book. It has been a long journey and I offer my profound thanks. -

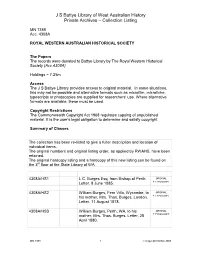

JS Battye Library of West Australian History Private Archives

J S Battye Library of West Australian History Private Archives – Collection Listing MN 1388 Acc. 4308A ROYAL WESTERN AUSTRALIAN HISTORICAL SOCIETY The Papers The records were donated to Battye Library by The Royal Western Historical Society (Acc.4308A) Holdings = 7.25m Access The J S Battye Library provides access to original material. In some situations, this may not be possible and alternative formats such as microfilm, microfiche, typescripts or photocopies are supplied for researchers’ use. Where alternative formats are available, these must be used. Copyright Restrictions The Commonwealth Copyright Act 1968 regulates copying of unpublished material. It is the user’s legal obligation to determine and satisfy copyright. Summary of Classes The collection has been re-listed to give a fuller description and location of individual items. The original numbers and original listing order, as applied by RWAHS, have been retained. The original hardcopy listing and a hardcopy of this new listing can be found on the 3rd floor at the State Library of WA 4308A/HS1 L.C. Burges Esq. from Bishop of Perth. ORIGINAL Letter, 8 June 1885. + TYPESCRIPT 4308A/HS2 William Burges, Fern Villa, Wycombe, to ORIGINAL his mother, Mrs. Thos. Burges, London. + TYPESCRIPT Letter, 11 August 1878. 4308A/HS3 William Burges, Perth, WA, to his ORIGINAL mother, Mrs. Thos. Burges. Letter, 28 + TYPESCRIPT April 1880. MN 1388 1 Copyright SLWA 2008 J S Battye Library of West Australian History Private Archives – Collection Listing 4308A/HS4 Tom (Burges) from Wm. Burges, ORIGINAL Liverpool, before sailing for Buenos + TYPESCRIPT Ayres. Letter, 9 June 1865. 4308A/HS5 Richard Burges, Esq. -

Public Law - an Australian Perspective

Public Law - An Australian Perspective Chief Justice Robert French AC Scottish Public Law Group 6 July 2012, Edinburgh Introduction Taxonomical disputes can arouse passions among lawyers out of proportion if not inversely proportional to the significance of their subject matter. The term 'Public Law' is a taxonomic term which does occasion debate about its scope and content. I will avoid entering into any debate on that question in this jurisdiction. My working definition for the purposes of this presentation is: that area of the law which is concerned with the scope, content and limits of official power, be it legislative, executive or judicial. So public law encompasses constitutional law and administrative law. In the Australian setting of written Commonwealth and State Constitutions, it is informed by the principle that there is no such thing as unlimited official power. There is therefore, no such thing as a power to make laws on any topic and for any purpose. There is no such thing as an unfettered discretion. Official discretions conferred by statute must be exercised consistently with the scope, objects and subject matter of the statute. Public law in Australia is manifested in the following ways: 1. By judicial review of the validity of legislation in direct or collateral challenges to: • A law of the Commonwealth Parliament on the basis that the law is not within its legislative competency as defined in the Constitution or otherwise transgresses constitutional prohibitions or guarantees; • A law of the State Parliament on the basis that the law is a law with respect to a subject matter exclusively within Commonwealth 2 legislative competency or otherwise transgresses constitutional prohibitions or guarantees. -

1: Theories of Law

1: Theories of Law.................................................................................................................................5 1.1 Theories of Law......................................................................................................................................5 1.1.1 Natural Law Theory.................................................................................................................5 1.1.2 Legal Positivism.......................................................................................................................6 1.1.3 Feminist Jurisprudence............................................................................................................7 1.1.4 Economic Analysis of the Law................................................................................................8 1.1.5 Critical Legal Theory...............................................................................................................8 2: Origins of Law....................................................................................................................................9 2.1 Development of Different Legal Systems.............................................................................................9 2.1.1 Civil Law System.....................................................................................................................9 2.1.2 Common Law System..............................................................................................................9 -

BURT, Francis Theodore Page, Sir (1918-2004) AC, KCMG, QC

BURT, Francis Theodore Page, Sir (1918-2004) AC, KCMG, QC Sir Francis was born in Cottesloe, a suburb of Perth in Western Australia and was educated at Guildford Grammar School. He studied law at the University of Western Australia and during World War 11 served in the Royal Australian Navy and the Royal Australian Air Force. Sir Francis was appointed as a Justice of the Supreme Court of Western Australia in 1969, a position he held until 1977 when he was promoted to Chief Justice. He retired in 1988. When the Governor of Western Australia, Gordon Reid, resigned in 1990, Sir Francis was appointed to succeed him and served as Governor until 1993. Sir Francis was afforded a State funeral on his death and is buried at Karrakatta Cemetery. The Francis Burt Chambers located in Allendale Square, Perth and the Francis Burt Law Education Centre and Museum in Stirling Gardens are named in his honour. Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Francis_Burt MN ACC Meterage / boxes Date donated CIU file Notes 2023 5681A 30cm January 2002 BA/PA/00/0343 5719A 20cm January 2002 5914A 12cm 13 January 2003 6368A 20cm 22 September 2004 9401A 3.06m 1 February 1995 9611A 60 cm (5 boxes) 1995 SUMMARY OF CLASSES ADDRESS BOOKS FILES PRINTED MATERIALS ADDRESSES (see also speeches) HISTORIES PROGRAMME AGENDAS INFORMATION SHEETS REFERENCE AGREEMENTS INTERVIEWS REMINISCENCES ANNUAL REPORTS INVITATIONS REPORTS APPOINTMENTS, COMMISSIONS LEGAL PAPERS RESERVED JUDGEMENTS ARTICLES (of service) MINUTES SPEECHES (see also addresses) ARTICLES (written paper) MEMORIALS SPONSORSHIP AUTOBIOGRAPHIES NEWSPAPER CUTTINGS TELEGRAM BIBLES NOTES TRANSFER BOOKLET NOTICE OF MEETING TRIBUTES BOOKS OF OPINIONS ORDER OF SERVICE VISITORS BOOKS CERTIFICATES PHOTOGRAPHS WILLS CORRESPONDENCE including PLANS LETTERBOOKS MN 1 Copyright SLWA ©2015 Acc.