Ubuntu Tutorial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Backbox Penetration Testing Never Looked So Lovely

DISTROHOPPER DISTROHOPPER Our pick of the latest releases will whet your appetite for new Linux distributions. Picaros Diego Linux for children. here are a few distributions aimed at children: Doudou springs to mind, Tand there’s also Sugar on a Stick. Both of these are based on the idea that you need to protect children from the complexities of the computer (and protect the computer from the children). Picaros Diego is different. There’s nothing stripped- down or shielded from view. Instead, it’s a normal Linux distro with a brighter, more kid-friendly interface. The desktop wallpaper perhaps best We were too busy playing Secret Mario on Picaros Diego to write a witty or interesting caption. exemplifies this. On one hand, it’s a colourful cartoon image designed to interest young file manager. In the programming category, little young for a system like this, but the it children. Some of the images on the we were slightly disappointed to discover it may well work for children on the upper end landscape are icons for games, and this only had Gambas (a Visual Basic-like of that age range. should encourage children to investigate the language), and not more popular teaching Overall, we like the philosophy of wrapping system rather than just relying on menus. languages like Scratch or a Python IDE. Linux is a child-friendly package, but not On the other hand, it still displays technical However, it’s based on Debian, so you do dumbing it down. Picaros Diego won’t work details such as the CPU usage and the RAM have the full range of software available for every child, but if you have a budding and Swap availability. -

Download Android Os for Phone Open Source Mobile OS Alternatives to Android

download android os for phone Open Source Mobile OS Alternatives To Android. It’s no exaggeration to say that open source operating systems rule the world of mobile devices. Android is still an open-source project, after all. But, due to the bundle of proprietary software that comes along with Android on consumer devices, many people don’t consider it an open source operating system. So, what are the alternatives to Android? iOS? Maybe, but I am primarily interested in open-source alternatives to Android. I am going to list not one, not two, but several alternatives, Linux-based mobile OSes . Top Open Source alternatives to Android (and iOS) Let’s see what open source mobile operating systems are available. Just to mention, the list is not in any hierarchical or chronological order . 1. Plasma Mobile. A few years back, KDE announced its open source mobile OS, Plasma Mobile. Plasma Mobile is the mobile version of the desktop Plasma user interface, and aims to provide convergence for KDE users. It is being actively developed, and you can even find PinePhone running on Manjaro ARM while using KDE Plasma Mobile UI if you want to get your hands on a smartphone. 2. postmarketOS. PostmarketOS (pmOS for short) is a touch-optimized, pre-configured Alpine Linux with its own packages, which can be installed on smartphones. The idea is to enable a 10-year life cycle for smartphones. You probably already know that, after a few years, Android and iOS stop providing updates for older smartphones. At the same time, you can run Linux on older computers easily. -

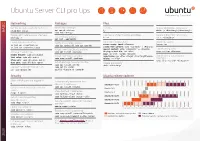

Ubuntu Server CLI Pro Tips

Ubuntu Server CLI pro tips Networking Packages Files Get the IP address of all interfaces Search for packages List files Create directories recursively networkctl status apt search <string> ls mkdir -p <directory1>/<directory2> BASIC snap find <string> Display all IP addresses of the host List files with permissions and dates Delete a directory recursively List available updates hostna m e -I ls -al rm -r <directory> apt list --upgradable Enable/disable interface Apply all available updates Common file operations Quick file search create empty: touch <filename> locate <q> ip link set <interface> up sudo apt update && sudo apt upgrade ip link set <interface> down create with content: echo "<content>" > <filename> Install from the Ubuntu archive: append content: echo "<content>" >> <filename> Search string in file Manage firewall rules sudo apt install <package> display a text file: cat <file> grep <string> <filename> enable firewall: sudo ufw enable copy: cp <file> <target filename> Install from the snap store: move/rename: mv <file> <target directory/filename> Search string recursively in list rules: sudo ufw status sudo snap install <package> delete: rm <file> directory allow port: sudo ufw allow <port> grep -Iris <string> <directory> deny port: sudo ufw deny <port> Which package provides this file? Create a directory sudo apt install apt-file mkdir <directory> Connect remotely through SSH sudo apt-file update ssh <user>@<host IP> apt-file <filename or command> Security Ubuntu release cadence Show which users are logged in Automatically -

Introduction to Fmxlinux Delphi's Firemonkey For

Introduction to FmxLinux Delphi’s FireMonkey for Linux Solution Jim McKeeth Embarcadero Technologies [email protected] Chief Developer Advocate & Engineer For quality purposes, all lines except the presenter are muted IT’S OK TO ASK QUESTIONS! Use the Q&A Panel on the Right This webinar is being recorded for future playback. Recordings will be available on Embarcadero’s YouTube channel Your Presenter: Jim McKeeth Embarcadero Technologies [email protected] | @JimMcKeeth Chief Developer Advocate & Engineer Agenda • Overview • Installation • Supported platforms • PAServer • SDK & Packages • Usage • UI Elements • Samples • Database Access FireDAC • Migrating from Windows VCL • midaconverter.com • 3rd Party Support • Broadway Web Why FMX on Linux? • Education - Save money on Windows licenses • Kiosk or Point of Sale - Single purpose computers with locked down user interfaces • Security - Linux offers more security options • IoT & Industrial Automation - Add user interfaces for integrated systems • Federal Government - Many govt systems require Linux support • Choice - Now you can, so might as well! Delphi for Linux History • 1999 Kylix: aka Delphi for Linux, introduced • It was a port of the IDE to Linux • Linux x86 32-bit compiler • Used the Trolltech QT widget library • 2002 Kylix 3 was the last update to Kylix • 2017 Delphi 10.2 “Tokyo” introduced Delphi for x86 64-bit Linux • IDE runs on Windows, cross compiles to Linux via the PAServer • Designed for server side development - no desktop widget GUI library • 2017 Eugene -

Ubuntu Linux Setup Guide

Ubuntu Linux Setup Guide For ThinkStation P330 Official Support of Ubuntu 16.04.5 and later Section 1 - BIOS Setup and Pre-Installation Steps The first step before installing Linux is to make sure BIOS is setup correctly • For UEFI/GPT Installations (Recommended): o Boot into BIOS by pressing the F1 function key at the “Lenovo” splash screen o Tab over to the Exit menu tab, and set OS Optimized Defaults to Enabled o Select “Yes” at the confirmation screen indicated below o Tab over to the Security menu tab, select Secure Boot, and set the option to Disabled o Press F10 to “Save and Exit” the BIOS setup menu o Insert the Ubuntu install media (either through USB or CD/DVD) o Power on the system and press the F12 function key whenever the following Lenovo splash screen appears o Select the Linux bootable installation media UEFI option from the F12 boot menu • For Legacy/MBR installations (not recommended): o Boot into BIOS by pressing the F1 function key at the “Lenovo” splash screen o Tab over to the Exit menu tab, and set OS Optimized Defaults to Disabled o Select “Yes” at the confirmation screen indicated below o Select F10 to “Save and Exit” BIOS o Insert the Ubuntu installation media (either through USB or CD/DVD) o Power on the system and press the F12 function key whenever the following Lenovo splash screen appears o Select the Linux bootable installation media Legacy option from the F12 boot menu Section 2 – Installing Ubuntu 16.04 LTS Please refer to the following instructions and screenshots on how to install Ubuntu 16.04 LTS on -

Linux Based Mobile Operating Systems

INSTITUTO SUPERIOR DE ENGENHARIA DE LISBOA Área Departamental de Engenharia de Electrónica e Telecomunicações e de Computadores Linux Based Mobile Operating Systems DIOGO SÉRGIO ESTEVES CARDOSO Licenciado Trabalho de projecto para obtenção do Grau de Mestre em Engenharia Informática e de Computadores Orientadores : Doutor Manuel Martins Barata Mestre Pedro Miguel Fernandes Sampaio Júri: Presidente: Doutor Fernando Manuel Gomes de Sousa Vogais: Doutor José Manuel Matos Ribeiro Fonseca Doutor Manuel Martins Barata Julho, 2015 INSTITUTO SUPERIOR DE ENGENHARIA DE LISBOA Área Departamental de Engenharia de Electrónica e Telecomunicações e de Computadores Linux Based Mobile Operating Systems DIOGO SÉRGIO ESTEVES CARDOSO Licenciado Trabalho de projecto para obtenção do Grau de Mestre em Engenharia Informática e de Computadores Orientadores : Doutor Manuel Martins Barata Mestre Pedro Miguel Fernandes Sampaio Júri: Presidente: Doutor Fernando Manuel Gomes de Sousa Vogais: Doutor José Manuel Matos Ribeiro Fonseca Doutor Manuel Martins Barata Julho, 2015 For Helena and Sérgio, Tomás and Sofia Acknowledgements I would like to thank: My parents and brother for the continuous support and being the drive force to my live. Sofia for the patience and understanding throughout this challenging period. Manuel Barata for all the guidance and patience. Edmundo Azevedo, Miguel Azevedo and Ana Correia for reviewing this document. Pedro Sampaio, for being my counselor and college, helping me on each step of the way. vii Abstract In the last fifteen years the mobile industry evolved from the Nokia 3310 that could store a hopping twenty-four phone records to an iPhone that literately can save a lifetime phone history. The mobile industry grew and thrown way most of the proprietary operating systems to converge their efforts in a selected few, such as Android, iOS and Windows Phone. -

Guest OS Compatibility Guide

Guest OS Compatibility Guide Guest OS Compatibility Guide Last Updated: September 29, 2021 For more information go to vmware.com. Introduction VMware provides the widest virtualization support for guest operating systems in the industry to enable your environments and maximize your investments. The VMware Compatibility Guide shows the certification status of operating system releases for use as a Guest OS by the following VMware products: • VMware ESXi/ESX Server 3.0 and later • VMware Workstation 6.0 and later • VMware Fusion 2.0 and later • VMware ACE 2.0 and later • VMware Server 2.0 and later VMware Certification and Support Levels VMware product support for operating system releases can vary depending upon the specific VMware product release or update and can also be subject to: • Installation of specific patches to VMware products • Installation of specific operating system patches • Adherence to guidance and recommendations that are documented in knowledge base articles VMware attempts to provide timely support for new operating system update releases and where possible, certification of new update releases will be added to existing VMware product releases in the VMware Compatibility Guide based upon the results of compatibility testing. Tech Preview Operating system releases that are shown with the Tech Preview level of support are planned for future support by the VMware product but are not certified for use as a Guest OS for one or more of the of the following reasons: • The operating system vendor has not announced the general availability of the OS release. • Not all blocking issues have been resolved by the operating system vendor. -

Ubuntu Server Guide Basic Installation Preparing to Install

Ubuntu Server Guide Welcome to the Ubuntu Server Guide! This site includes information on using Ubuntu Server for the latest LTS release, Ubuntu 20.04 LTS (Focal Fossa). For an offline version as well as versions for previous releases see below. Improving the Documentation If you find any errors or have suggestions for improvements to pages, please use the link at thebottomof each topic titled: “Help improve this document in the forum.” This link will take you to the Server Discourse forum for the specific page you are viewing. There you can share your comments or let us know aboutbugs with any page. PDFs and Previous Releases Below are links to the previous Ubuntu Server release server guides as well as an offline copy of the current version of this site: Ubuntu 20.04 LTS (Focal Fossa): PDF Ubuntu 18.04 LTS (Bionic Beaver): Web and PDF Ubuntu 16.04 LTS (Xenial Xerus): Web and PDF Support There are a couple of different ways that the Ubuntu Server edition is supported: commercial support and community support. The main commercial support (and development funding) is available from Canonical, Ltd. They supply reasonably- priced support contracts on a per desktop or per-server basis. For more information see the Ubuntu Advantage page. Community support is also provided by dedicated individuals and companies that wish to make Ubuntu the best distribution possible. Support is provided through multiple mailing lists, IRC channels, forums, blogs, wikis, etc. The large amount of information available can be overwhelming, but a good search engine query can usually provide an answer to your questions. -

Kubuntu Desktop Guide

Kubuntu Desktop Guide Ubuntu Documentation Project <[email protected]> Kubuntu Desktop Guide by Ubuntu Documentation Project <[email protected]> Copyright © 2004, 2005, 2006 Canonical Ltd. and members of the Ubuntu Documentation Project Abstract The Kubuntu Desktop Guide aims to explain to the reader how to configure and use the Kubuntu desktop. Credits and License The following Ubuntu Documentation Team authors maintain this document: • Venkat Raghavan The following people have also have contributed to this document: • Brian Burger • Naaman Campbell • Milo Casagrande • Matthew East • Korky Kathman • Francois LeBlanc • Ken Minardo • Robert Stoffers The Kubuntu Desktop Guide is based on the original work of: • Chua Wen Kiat • Tomas Zijdemans • Abdullah Ramazanoglu • Christoph Haas • Alexander Poslavsky • Enrico Zini • Johnathon Hornbeck • Nick Loeve • Kevin Muligan • Niel Tallim • Matt Galvin • Sean Wheller This document is made available under a dual license strategy that includes the GNU Free Documentation License (GFDL) and the Creative Commons ShareAlike 2.0 License (CC-BY-SA). You are free to modify, extend, and improve the Ubuntu documentation source code under the terms of these licenses. All derivative works must be released under either or both of these licenses. This documentation is distributed in the hope that it will be useful, but WITHOUT ANY WARRANTY; without even the implied warranty of MERCHANTABILITY or FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE AS DESCRIBED IN THE DISCLAIMER. Copies of these licenses are available in the appendices section of this book. Online versions can be found at the following URLs: • GNU Free Documentation License [http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html] • Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 [http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/] Disclaimer Every effort has been made to ensure that the information compiled in this publication is accurate and correct. -

Debian \ Amber \ Arco-Debian \ Arc-Live \ Aslinux \ Beatrix

Debian \ Amber \ Arco-Debian \ Arc-Live \ ASLinux \ BeatriX \ BlackRhino \ BlankON \ Bluewall \ BOSS \ Canaima \ Clonezilla Live \ Conducit \ Corel \ Xandros \ DeadCD \ Olive \ DeMuDi \ \ 64Studio (64 Studio) \ DoudouLinux \ DRBL \ Elive \ Epidemic \ Estrella Roja \ Euronode \ GALPon MiniNo \ Gibraltar \ GNUGuitarINUX \ gnuLiNex \ \ Lihuen \ grml \ Guadalinex \ Impi \ Inquisitor \ Linux Mint Debian \ LliureX \ K-DEMar \ kademar \ Knoppix \ \ B2D \ \ Bioknoppix \ \ Damn Small Linux \ \ \ Hikarunix \ \ \ DSL-N \ \ \ Damn Vulnerable Linux \ \ Danix \ \ Feather \ \ INSERT \ \ Joatha \ \ Kaella \ \ Kanotix \ \ \ Auditor Security Linux \ \ \ Backtrack \ \ \ Parsix \ \ Kurumin \ \ \ Dizinha \ \ \ \ NeoDizinha \ \ \ \ Patinho Faminto \ \ \ Kalango \ \ \ Poseidon \ \ MAX \ \ Medialinux \ \ Mediainlinux \ \ ArtistX \ \ Morphix \ \ \ Aquamorph \ \ \ Dreamlinux \ \ \ Hiwix \ \ \ Hiweed \ \ \ \ Deepin \ \ \ ZoneCD \ \ Musix \ \ ParallelKnoppix \ \ Quantian \ \ Shabdix \ \ Symphony OS \ \ Whoppix \ \ WHAX \ LEAF \ Libranet \ Librassoc \ Lindows \ Linspire \ \ Freespire \ Liquid Lemur \ Matriux \ MEPIS \ SimplyMEPIS \ \ antiX \ \ \ Swift \ Metamorphose \ miniwoody \ Bonzai \ MoLinux \ \ Tirwal \ NepaLinux \ Nova \ Omoikane (Arma) \ OpenMediaVault \ OS2005 \ Maemo \ Meego Harmattan \ PelicanHPC \ Progeny \ Progress \ Proxmox \ PureOS \ Red Ribbon \ Resulinux \ Rxart \ SalineOS \ Semplice \ sidux \ aptosid \ \ siduction \ Skolelinux \ Snowlinux \ srvRX live \ Storm \ Tails \ ThinClientOS \ Trisquel \ Tuquito \ Ubuntu \ \ A/V \ \ AV \ \ Airinux \ \ Arabian -

Official User's Guide

Official User Guide Linux Mint 18 Cinnamon Edition Page 1 of 52 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION TO LINUX MINT ......................................................................................... 4 HISTORY............................................................................................................................................4 PURPOSE...........................................................................................................................................4 VERSION NUMBERS AND CODENAMES.....................................................................................................5 EDITIONS...........................................................................................................................................6 WHERE TO FIND HELP.........................................................................................................................6 INSTALLATION OF LINUX MINT ........................................................................................... 8 DOWNLOAD THE ISO.........................................................................................................................8 VIA TORRENT...................................................................................................................................9 Install a Torrent client...............................................................................................................9 Download the Torrent file.........................................................................................................9 -

Xubuntu-Documentation-A4.Pdf

Xubuntu Documentation The Xubuntu documentation team. Xubuntu and Canonical are registered trademarks of Canonical Ltd. Xubuntu Documentation Copyright © 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015 The Xubuntu documentation team. Xubuntu and Canonical are registered trademarks of Canonical Ltd. Credits and License This documentation is maintained by the Xubuntu documentation team and is partly adapted from the Ubuntu documentation. The contributors to this documentation are: • David Pires (slickymaster) • Elfy (elfy) • Elizabeth Krumbach (lyz) • Jack Fromm (jjfrv8) • Jay van Cooten (skippersboss) • Kev Bowring (flocculant) • Krytarik Raido (krytarik) • Pasi Lallinaho (knome) • Sean Davis (bluesabre) • Stephen Michael Kellat (skellat) • Steve Dodier-Lazaro (sidi) • Unit 193 (unit193) The contributors to previous versions to this documentation are: • Cody A.W. Somerville (cody-somerville) • Freddy Martinez (freddymartinez9) • Jan M. (fijam7) • Jim Campbell (jwcampbell) • Luzius Thöny (lucius-antonius) This document is made available under the Creative Commons ShareAlike 2.5 License (CC-BY-SA). You are free to modify, extend, and improve the Ubuntu documentation source code under the terms of this license. All derivative works must be released under this license. This documentation is distributed in the hope that it will be useful, but WITHOUT ANY WARRANTY; without even the implied warranty of MERCHANTABILITY or FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE AS DESCRIBED IN THE DISCLAIMER. A copy of the license is available here: Creative Commons ShareAlike License. All trademarks