Georgma Clare Luck CHORAL CATHEDRAL

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Musical Heritage of the Lutheran Church Volume I

The Musical Heritage of the Lutheran Church Volume I Edited by Theodore Hoelty-Nickel Valparaiso, Indiana The greatest contribution of the Lutheran Church to the culture of Western civilization lies in the field of music. Our Lutheran University is therefore particularly happy over the fact that, under the guidance of Professor Theodore Hoelty-Nickel, head of its Department of Music, it has been able to make a definite contribution to the advancement of musical taste in the Lutheran Church of America. The essays of this volume, originally presented at the Seminar in Church Music during the summer of 1944, are an encouraging evidence of the growing appreciation of our unique musical heritage. O. P. Kretzmann The Musical Heritage of the Lutheran Church Volume I Table of Contents Foreword Opening Address -Prof. Theo. Hoelty-Nickel, Valparaiso, Ind. Benefits Derived from a More Scholarly Approach to the Rich Musical and Liturgical Heritage of the Lutheran Church -Prof. Walter E. Buszin, Concordia College, Fort Wayne, Ind. The Chorale—Artistic Weapon of the Lutheran Church -Dr. Hans Rosenwald, Chicago, Ill. Problems Connected with Editing Lutheran Church Music -Prof. Walter E. Buszin The Radio and Our Musical Heritage -Mr. Gerhard Schroth, University of Chicago, Chicago, Ill. Is the Musical Training at Our Synodical Institutions Adequate for the Preserving of Our Musical Heritage? -Dr. Theo. G. Stelzer, Concordia Teachers College, Seward, Nebr. Problems of the Church Organist -Mr. Herbert D. Bruening, St. Luke’s Lutheran Church, Chicago, Ill. Members of the Seminar, 1944 From The Musical Heritage of the Lutheran Church, Volume I (Valparaiso, Ind.: Valparaiso University, 1945). -

Southern Black Gospel Music: Qualitative Look at Quartet Sound

LIBERTY UNIVERSITY SOUTHERN BLACK GOSPEL MUSIC: QUALITATIVE LOOK AT QUARTET SOUND DURING THE GOSPEL ‘BOOM’ PERIOD OF 1940-1960 A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE SCHOOL OF MUSIC IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN ETHNOMUSICOLOGY BY BEATRICE IRENE PATE LYNCHBURG, V.A. April 2014 1 Abstract The purpose of this work is to identify features of southern black gospel music, and to highlight what makes the music unique. One goal is to present information about black gospel music and distinguishing the different definitions of gospel through various ages of gospel music. A historical accounting for the gospel music is necessary, to distinguish how the different definitions of gospel are from other forms of gospel music during different ages of gospel. The distinctions are important for understanding gospel music and the ‘Southern’ gospel music distinction. The quartet sound was the most popular form of music during the Golden Age of Gospel, a period in which there was significant growth of public consumption of Black gospel music, which was an explosion of black gospel culture, hence the term ‘gospel boom.’ The gospel boom period was from 1940 to 1960, right after the Great Depression, a period that also included World War II, and right before the Civil Rights Movement became a nationwide movement. This work will evaluate the quartet sound during the 1940’s, 50’s, and 60’s, which will provide a different definition for gospel music during that era. Using five black southern gospel quartets—The Dixie Hummingbirds, The Fairfield Four, The Golden Gate Quartet, The Soul Stirrers, and The Swan Silvertones—to define what southern black gospel music is, its components, and to identify important cultural elements of the music. -

Leonard Enns (B. 1948, Canada): Cello Sonata, 1St Movement Ben Bolt-Martin, Cello

Program Leonard Enns (b. 1948, Canada): Cello sonata, 1st movement Ben Bolt-Martin, cello Frank Ferko (b. 1950, USA): Elegy from Stabat Mater Cher Farrell, soprano soloist John Estacio (b. 1966, Canada): Mrs. Deegan from Four Eulogies John Estacio: Ella Sunlight from Four Eulogies Melanie Van Der Sluis, soprano soloist John Tavener (b. 1944, England): Svyati Ben Bolt-Martin, cello James Rolfe (b. 1961, Canada): Come, lovely and soothing death ~~~intermission~~~ Giles Swayne (b. 1946, England): Magnificat Arvo Pärt (b. 1935, Estonia): Magnificat Arvo Pärt: Spiegel im Spiegel Sarah Flatt, piano Ben Bolt-Martin, cello Morten Lauridsen (b. 1943, USA): O magnum mysterium Leonard Enns: This amazing day Please join us for an informal reception following the concert. Notes & Texts (notes written by L. Enns) On November 21, 1998 the DaCapo Chamber Choir performed its first concert here at St John’s. As a fledgling 13-voice ensemble we presented a concert including Arvo Pärt’s landmark Magnificat, also on tonight’s program. Today we celebrate our tenth anniversary concert; we have presented over fifty performances in this time. My one word — to some sixty different singers who have been part of the choir over the decade, to our board members, to our generous supporters, and especially to our audience — is a heartfelt, humble, and grateful thanks! For this anniversary year we have planned the season by returning to basics by considering the four classical elements of our world: earth, water, fire & air. Earth — mother earth, that takes old leaves, fallen rotting apples, the stubble of the fields, as well as our spent lives, and turns all into the hope for, and reality of, new life; transmuting earth that receives life exhausted and births hope and celebration — this is the starting (and startling!) point of our concert season. -

New Oxford History of Music Volume Ii

NEW OXFORD HISTORY OF MUSIC VOLUME II EDITORIAL BOARD J. A. WESTRUP (Chairman) GERALD ABRAHAM (Secretary) EDWARD J. DENT DOM ANSELM'HUGHES BOON WELLESZ THE VOLUMES OF THE NEW OXFORD HISTORY OF MUSIC I. Ancient and Oriental Music ii. Early Medieval Music up to 1300 in. Ars Nova and the Renaissance (c. 1300-1540) iv. The Age of Humanism (1540-1630) v. Opera and Church Music (1630-1750) vi. The Growth of Instrumental Music (1630-1750) vn. The Symphonic Outlook (1745-1790) VIIL The Age of Beethoven (1790-1830) ix. Romanticism (1830-1890) x. Modern Music (1890-1950) XL Chronological Tables and General Index ' - - SACRED AND PROFANE MUSIC (St. John's College, MS. B. Cambridge, 18.) Twelfth century EARLY MEDIEVAL MUSIC UP TO BOO EDITED BY DOM ANSELM HUGHES GEOFFREY CUMBERLEGE OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS LONDON NEWYORK TORONTO 1954 Oxford University Press, Amen House, London E.C.4 GLASGOW NEW YORK TORONTO MELBOURNE WELLINGTON BOMBAY CALCUTTA MADRAS KARACHI CAPE TOWN IBADAN Geoffrey Cumberlege, Publisher to the University PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN GENERAL INTRODUCTION THE present work is designed to replace the Oxford History of Music, first published in six volumes under the general editorship of Sir Henry Hadow between 1901 and 1905. Five authors contributed to that ambitious publication the first of its kind to appear in English. The first two volumes, dealing with the Middle Ages and the sixteenth century, were the work of H. E. Wooldridge. In the third Sir Hubert Parry examined the music of the seventeenth century. The fourth, by J. A. Fuller-Maitland, was devoted to the age of Bach and Handel; the fifth, by Hadow himself, to the period bounded by C. -

Luther's Hymn Melodies

Luther’s Hymn Melodies Style and form for a Royal Priesthood James L. Brauer Concordia Seminary Press Copyright © 2016 James L. Brauer Permission granted for individual and congregational use. Any other distribution, recirculation, or republication requires written permission. CONTENTS Preface 1 Luther and Hymnody 3 Luther’s Compositions 5 Musical Training 10 A Motet 15 Hymn Tunes 17 Models of Hymnody 35 Conclusion 42 Bibliography 47 Tables Table 1 Luther’s Hymns: A List 8 Table 2 Tunes by Luther 11 Table 3 Tune Samples from Luther 16 Table 4 Variety in Luther’s Tunes 37 Luther’s Hymn Melodies Preface This study began in 1983 as an illustrated lecture for the 500th anniversary of Luther’s birth and was presented four times (in Bronxville and Yonkers, New York and in Northhampton and Springfield, Massachusetts). In1987 further research was done on the question of tune authorship and musical style; the material was revised several times in the years that followed. As the 500th anniversary of the Reformation approached, it was brought into its present form. An unexpected insight came from examining the tunes associated with the Luther’s hymn texts: Luther employed several types (styles) of melody. Viewed from later centuries it is easy to lump all his hymn tunes in one category and label them “medieval” hymns. Over the centuries scholars have studied many questions about each melody, especially its origin: did it derive from an existing Gregorian melody or from a preexisting hymn tune or folk song? In studying Luther’s tunes it became clear that he chose melody structures and styles associated with different music-making occasions and groups in society. -

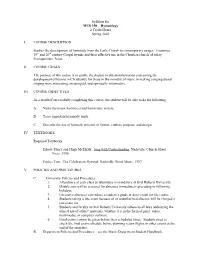

Syllabus for MUS 350—Hymnology 2 Credit Hours Spring 2003

Syllabus for MUS 350—Hymnology 2 Credit Hours Spring 2003 I. COURSE DESCRIPTION Studies the development of hymnody from the Early Church to contemporary usages. Examines 19th and 20th century Gospel hymns and their effective use in the Christian church of today. Prerequisities: None II. COURSE GOALS The purpose of this course is to enable the student to obtain information concerning the development of hymns in Christianity for those in the ministry of music in making congregational singing more interesting, meaningful, and spiritually informative. III. COURSE OBJECTIVES As a result of successfully completing this course, the student will be able to do the following: A. Name the major hymn text and hymn tune writers. B. Trace important hymnody tends. C. Describe the use of hymnals in terms of format, context, purpose, and design. IV. TEXTBOOKS Required Textbooks Eskew, Harry and Hugh McElrath. Sing with Understanding. Nashville: Church Street Press, 1995. Fettke, Tom. The Celebration Hymnal. Nashville: Word Music, 1997. V. POLICIES AND PROCEDURES C. University Policies and Procedures 1. Attendance at each class or laboratory is mandatory at Oral Roberts University. 2. Double cuts will be assessed for absences immediately preceding or following holidays. 3. Excessive absences can reduce a student’s grade or deny credit for the course. 4. Students taking a late exam because of an unauthorized absence will be charged a late exam fee. 5. Students and faculty at Oral Roberts University adhere to all laws addressing the ethical use of others’ materials, whether it is in the form of print, video, multimedia, or computer software. 6. -

Michael Z. Vinokouroff: a Profile and Inventory of His Papers And

MICHAEL Z. VINOKOUROFF: A PROFILE AND INVENTORY OF HIS PAPERS (Ms 81) AND PHOTOGRAPHS (PCA 243) in the Alaska Historical Library Louise Martin, Ph.D. Project coordinator and editor Alaska Department of Education Division ofState Libraries P.O. Box G Juneau Alaska 99811 1986 Martin, Louise. Michael Z. Vinokouroff: a profile and inventory of his papers (MS 81) and photographs (PCA 243) in the Alaska Historical Library / Louise Martin, Ph.D., project coordinator and editor. -- Juneau, Alaska (P.O. Box G. Juneau 99811): Alaska Department of Education, Division of State Libraries, 1986. 137, 26 p. : ill.; 28 cm. Includes index and references to photographs, church and Siberian material available on microfiche from the publisher. Partial contents: M.Z. Vinokouroff: profile of a Russian emigre scholar and bibliophile/ Richard A. Pierce -- It must be done / M.Z.., Vinokouroff; trans- lation by Richard A. Pierce. 1. Orthodox Eastern Church, Russian. 2. Siberia (R.S.F.S.R.) 3. Russian Orthodox Greek Catholic Church of America--Diocese of Alaska--Archives-- Catalogs. 4. Vinokour6ff, Michael Z., 1894-1983-- Library--Catalogs. 5. Soviet Union--Emigrationand immigration. 6. Authors, Russian--20th Century. 7. Alaska Historical Library-- Catalogs. I. Alaska. Division of State Libraries. II. Pierce, Richard A. M.Z. Vinokouroff: profile of a Russian emigre scholar and bibliophile. III. Vinokouroff, Michael Z., 1894- 1983. It must be done. IV. Title. DK246 .M37 Table of Contents Introduction ............................................. 1 “M.Z. Vinokouroff: Profile of a Russian Émigré Scholar and Bibliophile,” by Richard A. Pierce................... 5 Appendix: “IT MUST BE DONE!” by M.Z. Vinokouroff; translation by Richard A. -

A History of the Plagal-Amen Cadence

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 6-30-2016 A History Of The lP agal-Amen Cadence Jason Terry University of South Carolina Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Terry, J.(2016). A History Of The Plagal-Amen Cadence. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/ 3428 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A HISTORY OF THE PLAGAL-AMEN CADENCE by Jason Terry Bachelor of Arts Missouri Southern State University, 2009 Master of Music Baylor University, 2012 ____________________________________________________ Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Music Performance School of Music University of South Carolina 2016 Accepted by: Joseph Rackers, Major Professor John McKay, Director of Document Charles Fugo, Committee Member Marina Lomazov, Committee Member Lacy Ford, Senior Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies © Copyright by Jason Terry, 2016 All Rights Reserved. ii DEDICATION To my bride, with all my love. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Special thanks to the following individuals: to Swee Hong Lim (University of Toronto) for planting this research idea in my head in 2010; to Michael Morgan, for sharing your amazing collection of music; to the following individuals who, either through personal meetings or correspondences, shared their wisdom with me: Mary Louise (Mel) Bringle (Brevard College), J. Peter Burkholder (Indiana University), Sue Cole (University of Melbourne), Carl P. -

Album Booklet

Elizabeth Maconchy Nicola LeFanu Giles Swayne RELATI ONSHIPS Malu Lin violin Giles Swayne piano Relationships Elizabeth Maconchy (1907–1994) Elizabeth Maconchy Violin Sonata No. 2 Music for Violin & Piano by Violin Sonata No. 1 1. Molto moderato [4:32] 14. Moderato [6:29] Elizabeth Maconchy, Nicola LeFanu & Giles Swayne 2. Allegro molto [2:54] 15. Allegro scherzando [1:33] 3. Lento, quasi recitavo [5:17] 16. Lento [5:12] 4. Presto [4:25] 17. Toccata: allegro molto [3:25] Nicola LeFanu (b.1947) Giles Swayne Malu Lin violin Abstracts and a Frame 18. Echo, Op. 78 [5:13] Giles Swayne piano 5. Tranquillo e lento [1:12] 6. Quaver = 126 [1:35] Giles Swayne 7. Poco esitando ... rapido [1:28] 19. Farewell, Op. 151 [4:14] 8. Molto moderato [1:35] 9. Calmo assoluto [1:32] 10. Quaver = 126 [2:03] Total playing me [75:56] 11. Molto lento [2:22] 12. Tranquillo e lento [1:17] Giles Swayne (b.1946) 13. Duo, Op. 20 [19:26] All world premiere recordings About Malu Lin & Giles Swayne: ‘Malu Lin could walk on air’ The Yorkshire Evening Press ‘Giles Swayne, pianist, composer and wit, is a naonal treasure and should be paid more aenon.’ The Strad Relaonships: Maconchy, LeFanu & Swayne and the inescapable influences of Webern and Messiaen (who taught Swayne). Relaonships is an album formed from the various strands of familial, personal Elizabeth Maconchy: Violin Sonata No. 2 and musical connecons between the Maconchy’s second sonata was composed composers and performers involved in it. in 1943, during the war years. -

Local and Global Perspectives

RIPON COLLEGE CUDDESDON Christian congregational music: local and global perspectives 1-3 September 2011 Acknowledgements Conference Programme Committee Chair: Martyn Percy (Ripon College Cuddesdon) Monique Ingalls (University of Cambridge) Carolyn Landau (King’s College, London) Mark Porter (St Aldate’s, Oxford) Tom Wagner (Royal Holloway, University of London) Conference Administrators Julie Hutchence (Ripon College Cuddesdon) Sophie Farrant (Ripon College Cuddesdon) Conference Assistant Tom Albinson (Ripon College Cuddesdon) 2 Thursday 1st September 10.00 Registration & coffee Common Room 11.00 Welcome/opening address Graham Room Martyn Percy (Ripon College Cuddesdon) 11.30-1 Keynote plenary session 1: Performing theology through music (Graham Room) Chair: Monique Ingalls (University of Cambridge) Martin Stringer (University of Birmingham) - Worship, transcendence and muzak: reflections on Seigfried Kracauer’s ‘the hotel lobby’ Carol Muller (University of Pennsylvania) - Embodied belief: performing the theology of a South African messiah 1.00 Lunch Dining Hall 2-3.30 Panel session 1 Re-forming Identities Replacing Binaries Performing Identities Chair: Tom Wagner Chair: Gesa Hartje Chair: Jeffers Engelhardt Graham Room Colin Davison Room Seminar Room Deborah Justice (Indiana Marzanna Poplaw ska University) (University of North No, your worship music is Carolina at Chapel Hill) repetitious: subjective hearing, Contemporary musical the worship wars, and practice of Catholic and congregational identity Protestant churches in Central Java, Indonesia Laryssa Whittaker (Royal Joyce L. Irwin (Colgate Frances Wilkins Holloway) University) (University of Aberdeen) The healing people need “Worship wars” in Baroque Strengthening identity more than ARVs: HIV- and Enlightenment German through community singing: positive musicians and the Lutheranism praise nights in north-east Christian church in South Scotland's deep sea missions Africa Muriel E. -

ORTHODOX LITURGICAL HYMNS in GREGORIAN CHANT – Volume 1

ORTHODOX LITURGICAL HYMNS IN GREGORIAN CHANT – Volume 1 Ancient Modal Tradition of the West Introduction & Scores 2 We wish to express our deepest gratitude to all those who have blessed, supported and encouraged this project from the beginning - most especially, our beloved shepherd, His Eminence Irénée, Archbishop of Ottawa and Canada. Note: Feel free to reproduce and distribute this material - there is no copyright, unless otherwise noted (our heartfelt thanks to Fr. Columba Kelly of St. Meinrad’s Archabbey, for his kind permission to include some of his work here). Recorded examples are currently available at: https://thechoir.bandcamp.com/album/orthodox-hymns-in-gregorian-chant https://thechoir.bandcamp.com/album/orthodox-hymns-in-gregorian- chant-vol-2 2018 Holy Transfiguration Hermitage 3 Part I – An Overview Of Liturgical Chant, East & West Introduction .................................................................................... 6 History ........................................................................................... 7 Theory and Technique .................................................................. 15 Epilogue ...................................................................................... 31 A Few Notes On Performance ..................................................... 34 Part II – Music Intonations and Keys to Stikhera & Troparia .............................. 40 Hymns of Vespers Lord I Call – Tones 1 through 8 ...................................................................... 44 O Gladsome -

The Problem of Tonal Disunity in Sergeäł Rachmaninoff's All-Night

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2015 The Problem of Tonal Disunity in Sergeĭ Rachmaninoff's All-Night Vigil, op. 37 Olga Ellen Bakulina The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/850 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] THE PROBLEM OF TONAL DISUNITY IN SERGEĬ RACHMANINOFF’S ALL-NIGHT VIGIL, OP. 37 by OLGA (ELLEN) BAKULINA A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The City University of New York 2015 i © 2015 OLGA (ELLEN) BAKULINA All Rights Reserved ii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Music in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy ______ ____________________ Date L. Poundie Burstein Chair of Examining Committee ______ ____________________ Date Norman Carey Executive Officer William Rothstein, adviser Philip Ewell, first reader Poundie Burstein Blair Johnston ____________________ Supervisory Committee The City University of New York iii ABSTRACT THE PROBLEM OF TONAL DISUNITY IN SERGEĬ RACHMANINOFF’S ALL-NIGHT VIGIL, OP. 37 By Olga (Ellen) Bakulina Adviser: Professor William Rothstein Recent English-language scholarship has given considerable attention to the issue of tonal disunity, particularly the concepts of tonal pairing, directional tonality, and double-tonic complex.