Contributionsof Asa Don Dickinson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Feminism, Imperialism and Orientalism: the Challenge of the ‘Indian Woman’

FEMINISM, IMPERIALISM AND ORIENTALISM Women’s History Review, Vol. 7, No. 4, 1998 Feminism, Imperialism and Orientalism: the challenge of the ‘Indian woman’ JOANNA LIDDLE & SHIRIN RAI University of Warwick, Coventry, United Kingdom ABSTRACT This article examines the content and process of imperialist discourse on the ‘Indian woman’ in the writings of two North American women, one writing at the time of ‘first wave’ feminism, the other a key exponent of the ‘second wave’ of the movement. By analysing these writings, it demonstrates how the content of the discourse was reproduced over time with different but parallel effects in the changed political circumstances, in the first case producing the Western imperial powers as superior on the scale of civilisation, and in the second case producing Western women as the leaders of global feminism. It also identifies how the process of creating written images occurred within the context of each author’s social relations with the subject, the reader and the other authors, showing how an orientalist discourse can be produced through the author’s representation of the human subjects of whom she writes; how this discourse can be reproduced through the author’s uncritical use of earlier writers; and how the discourse can be activated in the audience through the author’s failure to challenge established cognitive structures in the reader. Introduction This article has two main aims. First, it examines how aspects of imperialist discourse on the colonised woman were taken up in Western women’s writing at the time of ‘first wave’ feminism, and reproduced in the ‘second wave’ of the movement within the context of the changing power relations between the imperial powers and the former colonies. -

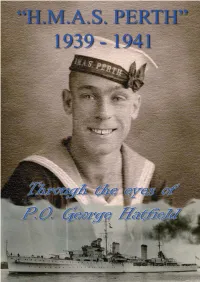

37845R CS3 Book Hatfield's Diaries.Indd

“H.M.A.S. PERTH” 1939 -1941 From the diaries of P.O. George Hatfield Published in Sydney Australia in 2009 Publishing layout and Cover Design by George Hatfield Jnr. Printed by Springwood Printing Co. Faulconbridge NSW 2776 1 2 Foreword Of all the ships that have flown the ensign of the Royal Australian Navy, there has never been one quite like the first HMAS Perth, a cruiser of the Second World War. In her short life of just less than three years as an Australian warship she sailed all the world’s great oceans, from the icy wastes of the North Atlantic to the steamy heat of the Indian Ocean and the far blue horizons of the Pacific. She survived a hurricane in the Caribbean and months of Italian and German bombing in the Mediterranean. One bomb hit her and nearly sank her. She fought the Italians at the Battle of Matapan in March, 1941, which was the last great fleet action of the British Royal Navy, and she was present in June that year off Syria when the three Australian services - Army, RAN and RAAF - fought together for the first time. Eventually, she was sunk in a heroic battle against an overwhelming Japanese force in the Java Sea off Indonesia in 1942. Fast and powerful and modern for her times, Perth was a light cruiser of some 7,000 tonnes, with a main armament of eight 6- inch guns, and a top speed of about 34 knots. She had a crew of about 650 men, give or take, most of them young men in their twenties. -

Sample Preview

Preview Sample A Publication of Complete Curriculum *LEUDOWDU0, © Complete Curriculum All rights reserved; No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior permission from the Publisher or Authorized Agent. Published in electronic format in the U.S.A. Preview Sample TM Acknowledgments Complete Curriculum’s K-12 curriculumKDV been team-developed by a consortium of teachers, administrators, educational and subject matter specialists, graphic artists and editors. In a collaborative environment, each professional participant contributed to ensuring the quality, integrity and effectiveness of each Compete Curriculum resource was commensurate with the required educational benchmarks and contemporary standards Complete Curriculum had set forth at the onset of this publishing program. Preview Sample Lesson 1 Vocabulary List One Frequently Used Words Objective: The student will recognize frequently encountered words, read them fluently, and understand the words and their history. Lesson 2 Make Me Laugh! Thomas Nast – “Cartoonist for America” Objective: The student will be introduced to analyzing the various ways that visual image-makers (graphic artists, illustrators) communicate information and affect impressions and opinions. Lesson 3 Written Humor The Ransom of Red Chief by O. Henry Objective: The student will analyze global themes, universal truths, and principles within and across texts to create a deeper understanding by drawing conclusions, making inferences, and synthesizing. Lesson 4 Writing Diary Entries Objective: The student will set a purpose, consider audience, and replicate authors’ styles and patterns when writing a narrative as a diary entry. Lesson 5 Preview Vocabulary Assessment—List One Journal Writing Objective: The student will demonstrate understanding of and familiarity with the Vocabulary words introduced in Vocabulary List One. -

“Low” Caste Women in India

Open Cultural Studies 2018; 2: 735-745 Research Article Jyoti Atwal* Embodiment of Untouchability: Cinematic Representations of the “Low” Caste Women in India https://doi.org/10.1515/culture-2018-0066 Received May 3, 2018; accepted December 7, 2018 Abstract: Ironically, feudal relations and embedded caste based gender exploitation remained intact in a free and democratic India in the post-1947 period. I argue that subaltern is not a static category in India. This article takes up three different kinds of genre/representations of “low” caste women in Indian cinema to underline the significance of evolving new methodologies to understand Black (“low” caste) feminism in India. In terms of national significance, Acchyut Kanya represents the ambitious liberal reformist State that saw its culmination in the constitution of India where inclusion and equality were promised to all. The movie Ankur represents the failure of the state to live up to the postcolonial promise of equality and development for all. The third movie, Bandit Queen represents feminine anger of the violated body of a “low” caste woman in rural India. From a dacoit, Phoolan transforms into a constitutionalist to speak about social justice. This indicates faith in Dr. B.R. Ambedkar’s India and in the struggle for legal rights rather than armed insurrection. The main challenge of writing “low” caste women’s histories is that in the Indian feminist circles, the discourse slides into salvaging the pain rather than exploring and studying anger. Keywords: Indian cinema, “low” caste feminism, Bandit Queen, Black feminism By the late nineteenth century due to certain legal and socio-religious reforms,1 space of the Indian family had been opened to public scrutiny. -

Katherine Mayo, Jabez Sunderland, and Indian Independence

Race Against Memory: Katherine Mayo, Jabez Sunderland, and Indian Independence Paul Teed A major event in the American debate over India's independence was the 1927 publication of Mother India, an explicitly pro-imperialist book by conservative Pennsylvania journalist Katherine Mayo. In the controversy over her book that ensued, American intellectuals struggled to understand India's culture, history, and national liberation movement in light of their nation's own historic experiences with revolution, nation building and civil war. Fawning in its support of British rule, and extravagantly critical of India's social practices, Mayo's book denied any analogy between India's quest for independence and America's own revolutionary past. Indeed, Mayo's engagement with India rested firmly upon a racially exclusive reading of American traditions that reflected deep contemporary concerns about America's role in the Philippines, immigration to the United States, and other domestic conditions. Responding to Mayo in his best-known work India in Bondage, Unitarian minister and long-time pro-India activist Jabez Sunderland sought not only to rehabilitate Indian culture in the wake of Mayo's attacks but also to position the mirror of American history to reflect more positively India's struggle for independence. Skillfully using the language of American collective memory that had emerged as the staple discourse of the American pro-India movement during the inter-war years, Sunderland rejected Mayo's racial nationalism and made direct comparisons between Indian leaders and the American revolutionaries.1 0026-3079/2003/4401-035S2.50/0 American Studies, 44:1-2 (Spring/Summer 2003): 35-57 35 36 Paul Teed This American debate over the Indian independence movement has received little attention from historians. -

Assessment of Adherence to the Core Elements of Hospital Antibiotic Stewardship Programs: a Survey of the Tertiary Care Hospitals in Punjab, Pakistan

antibiotics Article Assessment of Adherence to the Core Elements of Hospital Antibiotic Stewardship Programs: A Survey of the Tertiary Care Hospitals in Punjab, Pakistan Naeem Mubarak 1,* , Asma Sarwar Khan 1, Taheer Zahid 1 , Umm e Barirah Ijaz 1, Muhammad Majid Aziz 1, Rabeel Khan 1, Khalid Mahmood 2 , Nasira Saif-ur-Rehman 1,* and Che Suraya Zin 3,* 1 Department of Pharmacy Practice, Lahore Medical & Dental College, University of Health Sciences, Lahore 54600, Pakistan; [email protected] (A.S.K.); [email protected] (T.Z.); [email protected] (U.e.B.I.); [email protected] (M.M.A.); [email protected] (R.K.) 2 Institute of Information Management, University of the Punjab, Lahore 54000, Pakistan; [email protected] 3 Kulliyyah of Pharmacy, International Islamic University Malaysia, Kuantan 25200, Malaysia * Correspondence: [email protected] (N.M.); [email protected] (N.S.-u.-R.); [email protected] (C.S.Z.) Abstract: Background: To restrain antibiotic resistance, the Centers for Disease Control and Preven- tion (CDC), United States of America, urges all hospital settings to implement the Core Elements of Hospital Antibiotic Stewardship Programs (CEHASP). However, the concept of hospital-based antibiotic stewardship programs is relatively new in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Aim: To Citation: Mubarak, N.; Khan, A.S.; appraise the adherence of the tertiary care hospitals to seven CEHASPs. Design and Setting: A cross- Zahid, T.; Ijaz, U.e.B.; Aziz, M.M.; sectional study in the tertiary care hospitals in Punjab, Pakistan. Method: CEHASP assessment tool, Khan, R.; Mahmood, K.; (a checklist) was used to collect data from the eligible hospitals based on purposive sampling. -

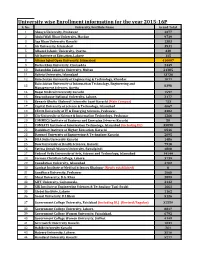

University Wise Enrollment Information for the Year 2015-16P S

University wise Enrollment information for the year 2015-16P S. No. University/Institute Name Grand Total 1 Abasyn University, Peshawar 4377 2 Abdul Wali Khan University, Mardan 9739 3 Aga Khan University Karachi 1383 4 Air University, Islamabad 3531 5 Alhamd Islamic University, Quetta. 338 6 Ali Institute of Education, Lahore 115 8 Allama Iqbal Open University, Islamabad 416607 9 Bacha Khan University, Charsadda 2449 10 Bahauddin Zakariya University, Multan 21385 11 Bahria University, Islamabad 13736 12 Balochistan University of Engineering & Technology, Khuzdar 1071 Balochistan University of Information Technology, Engineering and 13 8398 Management Sciences, Quetta 14 Baqai Medical University Karachi 1597 15 Beaconhouse National University, Lahore. 2177 16 Benazir Bhutto Shaheed University Lyari Karachi (Main Campus) 753 17 Capital University of Science & Technology, Islamabad 4067 18 CECOS University of IT & Emerging Sciences, Peshawar. 3382 19 City University of Science & Information Technology, Peshawar 1266 20 COMMECS Institute of Business and Emerging Sciences Karachi 50 21 COMSATS Institute of Information Technology, Islamabad (including DL) 35890 22 Dadabhoy Institute of Higher Education, Karachi 6546 23 Dawood University of Engineering & Technology Karachi 2095 24 DHA Suffa University Karachi 1486 25 Dow University of Health Sciences, Karachi 7918 26 Fatima Jinnah Women University, Rawalpindi 4808 27 Federal Urdu University of Arts, Science and Technology, Islamabad 14144 28 Forman Christian College, Lahore. 3739 29 Foundation University, Islamabad 4702 30 Gambat Institute of Medical Sciences Khairpur (Newly established) 0 31 Gandhara University, Peshawar 1068 32 Ghazi University, D.G. Khan 2899 33 GIFT University, Gujranwala. 2132 34 GIK Institute of Engineering Sciences & Technology Topi-Swabi 1661 35 Global Institute, Lahore 1162 36 Gomal University, D.I.Khan 5126 37 Government College University, Faislabad (including DL) (Revised/Regular) 32559 38 Government College University, Lahore. -

HEC RECOGNIZED LOCAL JOURNALS (Languages, Arts & Humanities)

HEC RECOGNIZED LOCAL JOURNALS (Languages, Arts & Humanities). The HEC is not responsible for the content of external internet sites. Y' CATEGORY JOURNALS: Acceptable for Tenure Track System, BPS appointments, HEC Approved Supervisor and Publication of research of Ph.D. work until 30th June 2016 S. No. Journal Name ISSN University Editor/Contact Person Subject w.e.f. Tel/Mob No. Fax No. E-mail Website The Iqbal review Iqbal Academy, 6th Floor, Aiwan-i- 1 0021-0773 Muhammad Suheyl Umar Iqbal Studies Jun-05 42-6314510 42-6314496 [email protected] http://www.allamaiqbal.com/ – A quarterly Journal Iqbal, Egerton Road, Lahore Department of English, University of May,12 2 Kashmir Journal of Language Research 1028-6640 Azad Jammu & Kashmir, Dr. Raja Nasim Akhter Language (in category 'Z' from Sep,08 99243131 Ext 2278 www.ajku.edu.pk Muzaffarabad till Apr,11) Journal of Research (Urdu) Formerly February 2015 (In 'Z' Department of Urdu Bahauddin 3 Journal of Research (Languages & Islamic 1726-9067 Dr.Rubina Tareen Urdu Category from Dec, 08 till 061-9210117 061-9210108 [email protected] http://www.bzu.edu.pk/jrlanguages/defalt.htm Zakariya University, Multan Studies) January 2015) February 2015 (In 'Z' Department of Urdu, Shah Abdul 4 Almas 1818-9296 Dr.M. Yusuf Khushk Urdu Category from Jun, 05 till 0243-9280291 0243-9280291 [email protected] http://www.salu.edu.pk/research/publication/journals/urdu/almas/ Latif University, Khairpur January 2015) February 2015 (In 'Z' Department of Urdu, Government 5 Tahqeeq Nama 1997-7611 Dr.M. Haroon Qadir Urdu Category from June 2005 042-99213339 - [email protected] http://gcu.edu.pk/TehqNama.htm College University, Lahore till January 2015) Gurmani Centre for Languages and February 2015 (In 'Z' 6 Bunyad 2225-5083 Literature, Lahore University of Dr. -

New Books on Women & Feminism

NEW BOOKS ON WOMEN & FEMINISM No. 50, Spring 2007 CONTENTS Scope Statement .................. 1 Politics/ Political Theory . 31 Anthropology...................... 1 Psychology ...................... 32 Art/ Architecture/ Photography . 2 Reference/ Bibliography . 33 Biography ........................ 3 Religion/ Spirituality . 34 Economics/ Business/ Work . 6 Science/ Mathematics/ Technology . 37 Education ........................ 8 Sexuality ........................ 37 Film/ Theater...................... 9 Sociology/ Social Issues . 38 Health/ Medicine/ Biology . 10 Sports & Recreation . 44 History.......................... 12 Women’s Movement/ General Women's Studies . 44 Humor.......................... 18 Periodicals ...................... 46 Language/ Linguistics . 18 Index: Authors, Editors, & Translators . 47 Law ............................ 19 Index: Subjects ................... 58 Lesbian Studies .................. 20 Citation Abbreviations . 75 Literature: Drama ................. 20 Literature: Fiction . 21 New Books on Women & Feminism is published by Phyllis Hol- man Weisbard, Women's Studies Librarian for the University of Literature: History & Criticism . 22 Wisconsin System, 430 Memorial Library, 728 State Street, Madi- son, WI 53706. Phone: (608) 263-5754. Email: wiswsl @library.wisc.edu. Editor: Linda Fain. Compilers: Amy Dachen- Literature: Mixed Genres . 25 bach, Nicole Grapentine-Benton, Christine Kuenzle, JoAnne Leh- man, Heather Shimon, Phyllis Holman Weisbard. Graphics: Dan- iel Joe. ISSN 0742-7123. Annual subscriptions are $8.25 for indi- Literature: Poetry . 26 viduals and $15.00 for organizations affiliated with the UW Sys- tem; $16.00 for non-UW individuals and non-profit women's pro- grams in Wisconsin ($30.00 outside the state); and $22.50 for Media .......................... 28 libraries and other organizations in Wisconsin ($55.00 outside the state). Outside the U.S., add $13.00 for surface mail to Canada, Music/ Dance .................... 29 $15.00 elsewhere; or $25.00 for air mail to Canada, $55.00 else- where. -

General Merit List of Reserved Seats for P.U Teachers for Admission to Pharm.D 1St Professional Morning Class Session 2020-2025

PUNJAB UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF PHARMACY UNIVERSITY OF THE PUNJAB, LAHORE. General Merit list of Reserved seats for P.U Teachers for Admission to Pharm.D 1st Professional Morning class session 2020-2025. Note: Any Candidate who has submitted the complete admission form on college admission portal, i.e., admissionpucp.edu.pk or pucp.edu.pk with fullfilling all requirements, but his/her name is not inculde in the General merit list should report to the college admission office before 03-11-2020. No complaint will be entertained after 03-11-2020. The University Reserves the Right to correct any Typographical Error, Ommision etc. Sr. Year of % Merit Late Year Final Merit Form ID Name of Student Father name Status No. Passing Marks Deduction Marks 1 DB5866 MUHAMMAD HAMZA SHOAIB HAJI MUHAMMAD SHOAIB KHAN 2020 94.655 0 94.655 Son 2 DB11359 HAFIZA SARA HASSAN HAFIZ HASAN MADNI 2020 94.255 0 94.255 Daughter 3 DB6061 KHANSA IJAZ MUHAMMAD IJAZ 2020 91.236 0 91.236 Daughter 4 DB7458 IZZA ALMATEEN SOHAIL SOHAIL AFZAL TAHIR 2020 90.273 0 90.273 Daughter Daughter 5 DB10100 AYESHA KHALIL KHALIL AHMAD 2020 88.836 0 88.836 Letter Required 6 DB5267 AZQA AHMAD AHMAD ISLAM 2020 88.764 0 88.764 Daughter 7 DB6048 MUSFIRA FATIMA MALIK AHMED SHER AWAN 2020 87.400 0 87.400 Daughter 8 DB8059 AREEBA AMER SYED AMER MAHMOOD 2020 86.182 0 86.182 Daughter 9 DB5799 SHEHROZE RAUF SHAKOORI ABDUL RAUF SHAKOORI 2020 83.132 0 83.132 Son Daughter 10 DB8639 AYESHA SOHAIL BUTT 2019 83.436 2 81.436 Letter Required 11 DB12029 UM E ABIHA SIKANDARR SIKANDAR HAYAT KHAN 2017 80.582 6 -

From Suffrage to Substantive Human Rights: the Continuing Journey for Racially Marginalized Women

Western New England Law Review Volume 42 42 Issue 3 Article 6 2020 FROM SUFFRAGE TO SUBSTANTIVE HUMAN RIGHTS: THE CONTINUING JOURNEY FOR RACIALLY MARGINALIZED WOMEN Bandana Purkayastha [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.wne.edu/lawreview Recommended Citation Bandana Purkayastha, FROM SUFFRAGE TO SUBSTANTIVE HUMAN RIGHTS: THE CONTINUING JOURNEY FOR RACIALLY MARGINALIZED WOMEN, 42 W. New Eng. L. Rev. 419 (2020), https://digitalcommons.law.wne.edu/lawreview/vol42/iss3/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Review & Student Publications at Digital Commons @ Western New England University School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Western New England Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Western New England University School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WESTERN NEW ENGLAND LAW REVIEW Volume 42 2020 Issue 3 FROM SUFFRAGE TO SUBSTANTIVE HUMAN RIGHTS: THE CONTINUING JOURNEY FOR RACIALLY MARGINALIZED WOMEN BANDANA PURKAYASTHA* This Article highlights racially marginalized women’s struggles to substantively access rights. Suffrage was meant to acquire political rights for women, and through that mechanism, move towards greater equality between women and men in the public and private spheres. Yet, racial minority women, working class and immigrant women, among others, continued to encounter a series of political, civil, economic, cultural, and social boundaries that deprived them of access to rights. From the struggles of working-class immigrant women for economic rights, to equal pay, and better work conditions, to the struggles of Japanese American women who were interned because they were assumed to be “the enemy” of the state, the history of the twentieth century is replete with contradictions of what was achieved in the quest for rights and what was suppressed. -

Translating Race and Castejohs 1389 62..79

Journal of Historical Sociology Vol. 24 No. 1 March 2011 DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-6443.2011.01389.x Translating Race and Castejohs_1389 62..79 NICO SLATE* Abstract In the late nineteenth century, Indian and African American social reformers began to compare struggles against racial oppression in the United States with movements against caste oppression in India. The majority of these reformers ignored what was lost in translating messy particularities of identity, status and hierarchy into the words “race” and “caste” and then again translating between these words. While exploring the limitations of such a double translation, this article argues that race/caste analogies were often utilized in opposition to white supremacy, caste oppression, and other forms of injustice. ***** In 1873, Jotirao Phule marshaled the history of race in the United States to attack caste prejudice in India. An eloquent critic of caste oppression, Phule had authored several books and founded an organization, the Satyashodak Samaj, that aimed to represent the “bahujan” or majority of India that Phule argued had been subju- gated by a Brahman elite (Omvedt 1976; O’Hanlon 1985). Phule entitled his attack on Brahmanism Slavery and dedicated it: To the good people of the United States as a token of admiration for their sublime disinterested and self sacrificing devotion in the cause of Negro Slavery; and with an earnest desire, that my country men may take their noble example as their guide in the emancipation of their Shudra Brethren from the trammels of Brahmin thralldom (Phule 1873). In his dedication, as well as the title of his book, Phule wielded elastic notions of freedom and slavery to denounce caste hierarchy.