Rupaul's Drag Race

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bianca Del Rio Floats Too, B*TCHES the ‘Clown in a Gown’ Talks Death-Drop Disdain and Why She’S Done with ‘Drag Race’

Drag Syndrome Barred From Tanglefoot: Discrimination or Protection? A Guide to the Upcoming Democratic Presidential Kentucky Marriage Battle LGBTQ Debates Bianca Del Rio Floats Too, B*TCHES The ‘Clown in a Gown’ Talks Death-Drop Disdain and Why She’s Done with ‘Drag Race’ PRIDESOURCE.COM SEPT.SEPT. 12, 12, 2019 2019 | | VOL. VOL. 2737 2737 | FREE New Location The Henry • Dearborn 300 Town Center Drive FREE PARKING Great Prizes! Including 5 Weekend Join Us For An Afternoon Celebration with Getaways Equality-Minded Businesses and Services Free Brunch Sunday, Oct. 13 Over 90 Equality Vendors Complimentary Continental Brunch Begins 11 a.m. Expo Open Noon to 4 p.m. • Free Parking Fashion Show 1:30 p.m. 2019 Sponsors 300 Town Center Drive, Dearborn, Michigan Party Rentals B. Ella Bridal $5 Advance / $10 at door Family Group Rates Call 734-293-7200 x. 101 email: [email protected] Tickets Available at: MiLGBTWedding.com VOL. 2737 • SEPT. 12 2019 ISSUE 1123 PRIDE SOURCE MEDIA GROUP 20222 Farmington Rd., Livonia, Michigan 48152 Phone 734.293.7200 PUBLISHERS Susan Horowitz & Jan Stevenson EDITORIAL 22 Editor in Chief Susan Horowitz, 734.293.7200 x 102 [email protected] Entertainment Editor Chris Azzopardi, 734.293.7200 x 106 [email protected] News & Feature Editor Eve Kucharski, 734.293.7200 x 105 [email protected] 12 10 News & Feature Writers Michelle Brown, Ellen Knoppow, Jason A. Michael, Drew Howard, Jonathan Thurston CREATIVE Webmaster & MIS Director Kevin Bryant, [email protected] Columnists Charles Alexander, -

Feminist Media Studies “She Is Not Acting, She

This article was downloaded by: [University of California, Berkeley] On: 06 January 2014, At: 10:16 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Feminist Media Studies Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rfms20 “She Is Not Acting, She Is” Sabrina Strings & Long T. Bui Published online: 27 Aug 2013. To cite this article: Sabrina Strings & Long T. Bui , Feminist Media Studies (2013): “She Is Not Acting, She Is”, Feminist Media Studies, DOI: 10.1080/14680777.2013.829861 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2013.829861 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content. -

A Killjoy's Introduction to Religion

Buzzsprout MY PODCASTS MY PROFILE HELP LOG OUT Keeping It 101: A Killjoy's Introduction to Religion Episodes Players Website Directories Resources Podcast Settings Stats Back to Episode Transcript Export Done, Back to Episode Episode: Extracurriculars: Ru-ligion Ru-vealed! the T on Religion & Drag Race Last Saved 14 minutes ago. Ilyse Keeping It 101: A Killjoy's Introd… This is Keeping it 101, a killjoy's introduction to religion podcast. Extracurriculars: Ru-ligion Ru-vealed! the T on Religion & Drag Race Megan What's up nerds? Share Info 00:00 | 59:11 Ilyse Hi. Hello. I'm Ilyse Morgenstein Fuerst a professional and professorial killjoy living, Speakers working, and raising killjoys on the traditional and ancestral lands of the Abenaki Ilyse people. I'm a scholar of Islam, imperialism, racial ization of Muslims and the history of Megan religion Located at the University of Vermont. RPDR Megan Simpsons Hi. Hello. I'm Megan Goodwin, the other unapologetic feminist killjoy on keeping at ADD SPEAKER 101 Broadcasting. Get it From the Land of the Wabenaki Confederacy, the Abenaki and the Aucocisco Peoples. I'm a scholar of gender, sexuality, white supremacy, minority religions, politics and America, located at Northeastern University--slash currently, my couch--and I coordinate Sacred Writes, public scholarship on religion, a Luce funded project that helps scholars and nerds like yourself share their expertise with folks who don't talk and study and think about religion all the time. Megan Hey, it's an extracurricular episode. Schools fun and all, but it's after school when the magic of learning really happens. -

The History and Representation of Drag in Popular Culture; How We Got to Rupaul

MASARYK UNIVERSITY FACULTY OF ARTS The History and Representation of Drag in Popular Culture; How We Got to RuPaul Bachelor's thesis MICHAELA SEVEROVÄ Supervisor: Jeffrey Alan Vanderziel, B.A. Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Brno 2021 MUNI ARTS THE HISTORY AND REPRESENTATION OF DRAG IN POPULAR CULTURE; HOW WE GOT TO RUPAUL Bibliographic record Author: Michaela Severovä Faculty of Arts Masaryk University Title of Thesis: The History and Representation of Drag in Popular Culture; How We Got to RuPaul Degree Program: English Language and Literature Supervisor: Jeffrey Alan Vanderziel, B.A. Year: 2021 Number of Pages: 72 Keywords: drag queens, RuPauVs Drag Race, drag, LGBTQ+, representation, queer culture, sexuality 2 THE HISTORY AND REPRESENTATION OF DRAG IN POPULAR CULTURE; HOW WE GOT TO RUPAUL Abstract This bachelor thesis deals with drag and its representation in popular culture, focus• ing on RuPaul's Drag Race. It analyses the representation of drag by explaining some basic terms and the study of the history of drag. It then analyses the evolution of the representation of drag queens in movies and shows. The main focus of this thesis is the American TV show RuPaul's Drag Race and how it changed the portrayal of drag and the LGBTQ+ community in popular culture. The thesis questions if the show is as progressive and diverse as it proclaims to be and if it shows the authentic image of drag culture. 3 THE HISTORY AND REPRESENTATION OF DRAG IN POPULAR CULTURE; HOW WE GOT TO RUPAUL Declaration I hereby declare that this thesis with title The History and Representation of Drag in Popular Culture; How We Got to RuPaul I submit for assessment is entirely my own work and has not been taken from the work of others save to the extent that such work has been cited and acknowledged within the text of my thesis. -

Non-Fiction Books for Adults a Select List of Brown County Library Adult Non-Fiction Books Click on Each Title Below to See the Library's Catalog Record

Non-Fiction Books for Adults A Select List of Brown County Library Adult Non-Fiction Books Click on each title below to see the library's catalog record. Then click on the title in the record for details, current availability, or to place a hold. For additional books & items on this theme, ask your librarian or search the library’s online catalog. LGBTQ+ History And the Band Played On: Politics, People, and the AIDS Epidemic by Randy Shilts The Book of Pride: LGBTQ Heroes Who Changed the World by Mason Funk The Deviant’s War: The Homosexual vs. the United States of America by Eric Cervini How to Survive a Plague: The Inside Story of How Citizens and Science Tamed AIDS by David France Legendary Children: The First Decade of RuPaul’s Drag Race and the Last Century of Queer Life by Tom Fitzgerald Love Wins: The Lovers and Lawyers Who Fought the Landmark Case for Marriage Equality By Debbie Cenziper Queer: A Graphic History by Meg-John Barker (graphic novel) The Stonewall Reader by The New York Public Library Transgender History: The Roots of Today’s Revolution by Susan Stryker We Are Everywhere: Protest, Power, and Pride In The History of Queer Liberation by Matthew Riemer and Leighton Brown We’ve Been Here All Along: Wisconsin’s Early Gay History by R. Richard Wagner The World Only Spins Forward: The Ascent of Angels in America by Isaac Butler and Dan Kois Books for Allies, Parents, and Education (* = in Parent-Teacher Collection) Becoming an Ally to the Gender-expansive Child: A Guide for Parents and Carers by Anna Bianchi* Gender: A Graphic -

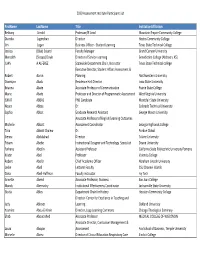

2020 Assessment Institute Participant List Firstname Lastname Title

2020 Assessment Institute Participant List FirstName LastName Title InstitutionAffiliation Bethany Arnold Professor/IE Lead Mountain Empire Community College Diandra Jugmohan Director Hostos Community College Jim Logan Business Officer ‐ Student Learning Texas State Technical College Jessica (Blair) Soland Faculty Manager Grand Canyon University Meredith (Stoops) Doyle Director of Service‐Learning Benedictine College (Atchison, KS) JUAN A ALFEREZ Statewide Department Chair, Instructor Texas State Technical college Executive Director, Student Affairs Assessment & Robert Aaron Planning Northwestern University Osomiyor Abalu Residence Hall Director Iowa State University Brianna Abate Associate Professor of Communication Prairie State College Marie Abate Professor and Director of Programmatic Assessment West Virginia University ISMAT ABBAS PhD Candidate Montclair State University Noura Abbas Dr. Colorado Technical University Sophia Abbot Graduate Research Assistant George Mason University Associate Professor of English/Learning Outcomes Michelle Abbott Assessment Coordinator Georgia Highlands College Talia Abbott Chalew Dr. Purdue Global Sienna Abdulahad Director Tulane University Fitsum Abebe Instructional Designer and Technology Specialist Doane University Farhana Abedin Assistant Professor California State Polytechnic University Pomona Kristin Abel Professor Valencia College Robert Abel Jr Chief Academic Officer Abraham Lincoln University Leslie Abell Lecturer Faculty CSU Channel Islands Dana Abell‐Huffman Faculty instructor Ivy Tech Annette -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Reading RuPaul's Drag Race: Queer Memory, Camp Capitalism, and RuPaul's Drag Empire Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0245q9h9 Author Schottmiller, Carl Publication Date 2017 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Reading RuPaul’s Drag Race: Queer Memory, Camp Capitalism, and RuPaul’s Drag Empire A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Culture and Performance by Carl Douglas Schottmiller 2017 © Copyright by Carl Douglas Schottmiller 2017 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Reading RuPaul’s Drag Race: Queer Memory, Camp Capitalism, and RuPaul’s Drag Empire by Carl Douglas Schottmiller Doctor of Philosophy in Culture and Performance University of California, Los Angeles, 2017 Professor David H Gere, Chair This dissertation undertakes an interdisciplinary study of the competitive reality television show RuPaul’s Drag Race, drawing upon approaches and perspectives from LGBT Studies, Media Studies, Gender Studies, Cultural Studies, and Performance Studies. Hosted by veteran drag performer RuPaul, Drag Race features drag queen entertainers vying for the title of “America’s Next Drag Superstar.” Since premiering in 2009, the show has become a queer cultural phenomenon that successfully commodifies and markets Camp and drag performance to television audiences at heretofore unprecedented levels. Over its nine seasons, the show has provided more than 100 drag queen artists with a platform to showcase their talents, and the Drag Race franchise has expanded to include multiple television series and interactive live events. The RuPaul’s Drag Race phenomenon provides researchers with invaluable opportunities not only to consider the function of drag in the 21st Century, but also to explore the cultural and economic ramifications of this reality television franchise. -

Print Format

Paideia High School Summer Reading 2021 © Paideia School Library, 1509 Ponce de Leon Avenue, NE. Atlanta, Georgia 30307 (404) 377-3491 PAIDEIA HIGH SCHOOL Summer Reading Program Marianne Hines – All High School students should read a minimum of THREE books “Standing at the Crossroads” – Read THREE books by American over the summer. See below for any specific books assigned for your authors (of any racial or ethnic background) and be prepared to write grade and/or by your fall term English teacher. You will write about your first paper on one of these books. your summer reading at the beginning of the year. Free choice books can be chosen from the High School summer Tally Johnson – Read this book, plus TWO free choice books = reading booklet, or choose any other books that intrigue you. THREE total Need help deciding on a book, or have other questions? “The Ties That Bind Us” – Little Fires Everywhere by Celeste Ng Email English teacher Marianne Hines at [email protected] Sarah Schiff – Read this book plus TWO free choice books = THREE total or librarian Anna Watkins at [email protected]. "Yearning to Breathe Free” – Kindred by Octavia Butler. 9th & 10th grade summer reading Jim Veal – Read the assigned book plus TWO free choice books = THREE total Read any THREE fiction or non-fiction books of your own choosing. “The American West” – Shane by Jack Schaefer “Coming Across” – The Best We Could Do by Thi Bui 11th & 12th grade summer reading by teacher and class If your fall term English teacher has not listed specific assignments, read a total of THREE fiction or non-fiction books of your own choice. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Reading Rupaul's Drag Race

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Reading RuPaul’s Drag Race: Queer Memory, Camp Capitalism, and RuPaul’s Drag Empire A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Culture and Performance by Carl Douglas Schottmiller 2017 © Copyright by Carl Douglas Schottmiller 2017 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Reading RuPaul’s Drag Race: Queer Memory, Camp Capitalism, and RuPaul’s Drag Empire by Carl Douglas Schottmiller Doctor of Philosophy in Culture and Performance University of California, Los Angeles, 2017 Professor David H Gere, Chair This dissertation undertakes an interdisciplinary study of the competitive reality television show RuPaul’s Drag Race, drawing upon approaches and perspectives from LGBT Studies, Media Studies, Gender Studies, Cultural Studies, and Performance Studies. Hosted by veteran drag performer RuPaul, Drag Race features drag queen entertainers vying for the title of “America’s Next Drag Superstar.” Since premiering in 2009, the show has become a queer cultural phenomenon that successfully commodifies and markets Camp and drag performance to television audiences at heretofore unprecedented levels. Over its nine seasons, the show has provided more than 100 drag queen artists with a platform to showcase their talents, and the Drag Race franchise has expanded to include multiple television series and interactive live events. The RuPaul’s Drag Race phenomenon provides researchers with invaluable opportunities not only to consider the function of drag in the 21st Century, but also to explore the cultural and economic ramifications of this reality television franchise. ii While most scholars analyze RuPaul’s Drag Race primarily through content analysis of the aired television episodes, this dissertation combines content analysis with ethnography in order to connect the television show to tangible practices among fans and effects within drag communities. -

From the Love Ball to Rupaul: the Mainstreaming of Drag in the 1990S

FROM THE LOVE BALL TO RUPAUL: THE MAINSTREAMING OF DRAG IN THE 1990S by JEREMIAH DAVENPORT Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Music CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY August, 2017 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the dissertation of Jeremiah Davenport candidate for the degree of PhD, Musicology. Committee Chair Daniel Goldmark Committee Member Georgia Cowart Committee Member Francesca Brittan Committee Member Robert Spadoni Date of Defense April 26, 2017 *We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein. 2 Acknowledgements Thank you from the bottom of my heart to everyone who helped this dissertation come to fruition. I want to thank my advisor Dr. Daniel Goldmark, the Gandalf to my Frodo, who has guided me through the deepest quandaries and quagmires of my research as well as some of the darkest times of my life. I believe no one understands the way my mind works as well as Daniel and I owe him a tremendous debt of gratitude for helping me find the language and tools to write about my community and the art form I love. I also want to thank Dr. Georgia Cowart for helping me find my voice and for her constant encouragement. I am grateful to Dr. Francesca Brittan for her insights that allowed me to see the musicologist in myself more clearly and her unwavering support of this project. I also would like to thank Dr. Robert Spadoni for expanding my analytical skills and for constantly allowing me to pick his brain about drag, movies, and life. -

The History and Representation of Drag in Popular Culture; How We Got to Rupaul

FACULTY OF ARTS The History and Representation of Drag in Popular Culture; How We Got to RuPaul Bachelor's thesis MICHAELA SEVEROVÁ Supervisor: Jeffrey Alan Vanderziel, B.A. Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Brno 2021 THE HISTORY AND REPRESENTATION OF DRAG IN POPULAR CULTURE; HOW WE GOT TO RUPAUL Bibliographic record Author: Michaela Severová Faculty of Arts Masaryk University Title of Thesis: The History and Representation of Drag in Popular Culture; How We Got to RuPaul Degree Program: English Language and Literature Supervisor: Jeffrey Alan Vanderziel, B.A. Year: 2021 Number of Pages: 72 Keywords: drag queens, RuPaul´s Drag Race, drag, LGBTQ+, representation, queer culture, sexuality 2 THE HISTORY AND REPRESENTATION OF DRAG IN POPULAR CULTURE; HOW WE GOT TO RUPAUL Abstract This bachelor thesis deals with drag and its representation in popular culture, focus- ing on RuPaul´s Drag Race. It analyses the representation of drag by explaining some basic terms and the study of the history of drag. It then analyses the evolution of the representation of drag queens in movies and shows. The main focus of this thesis is the American TV show RuPaul´s Drag Race and how it changed the portrayal of drag and the LGBTQ+ community in popular culture. The thesis questions if the show is as progressive and diverse as it proclaims to be and if it shows the authentic image of drag culture. 3 THE HISTORY AND REPRESENTATION OF DRAG IN POPULAR CULTURE; HOW WE GOT TO RUPAUL Declaration I hereby declare that this thesis with title The History and Representation of Drag in Popular Culture; How We Got to RuPaul I submit for assessment is entirely my own work and has not been taken from the work of others save to the extent that such work has been cited and acknowledged within the text of my thesis. -

Entrepreneurial 'Insta-Drag': an Analysis Of

MAKINGS, 2021 Volume 2 Issue 1 ISSN 2752-3861 (Online) makingsjournal.com Entrepreneurial ‘Insta-Drag’: An Analysis of Nottingham Based Drag Performers’ Social Media Profiles Zack Ditch1 PhD Researcher, School of Arts and Humanities, Nottingham Trent University, NG11 8NS, England Email: [email protected] Abstract Drag has proven to be a subject of particular interest in the fields of gender and queer studies, with recent debates exploring the neoliberalisation, globalisation, and deradicalization of the art form. This is usually attributed to the success of the reality TV show RuPaul’s Drag Race and further research identifies that neoliberal notions of self- branding and competition have infiltrated drag due to this reality tv phenomenon and the heightened visibility of drag. Yet, most of these studies explore drag in the United States, leaving a gap that fails to explore drag cultures in other national contexts, their relation to neoliberalism, and notions of drag-related entrepreneurialism to engage the creative industry. Where current literature exploring UK-based drag does exist, there is a heavy focus on metropolitan cities such as London, underrepresenting smaller regional queer communities in mid-sized cities, like Nottingham. Surprisingly, little work utilises Instagram as a valuable resource even though it provides drag performers a platform of self-expression, branding and competition in facilitating a networked access to images, posts, captions, bios, and engagement-rates of these queer communities. Analyses of drag performer Instagram profiles might then reflect and develop work surrounding the entrepreneurial attitudes of drag performers. This paper seeks to occupy these blindspots within drag-based research by using an alternative approach that engages with 20 Instagram Profiles of Nottingham-based drag performers through a triangulation of data analysis methods.