Investigation Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2016 This Page Is Intentionally Left Blank

Annual Report 2016 This page is intentionally left blank 2 This report is published in accordance with: l the Railway Safety Directive 2004/49/EC; l the Railways and Transport Safety Act 2003; and l the Railways (Accident Investigation and Reporting) Regulations 2005. © Crown copyright 2017 You may re-use this document/publication (not including departmental or agency logos) free of charge in any format or medium. You must re-use it accurately and not in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as Crown copyright and you must give the title of the source publication. Where we have identified any third party copyright material you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. This document/publication is also available at www.gov.uk/raib. Any enquiries about this publication should be sent to: RAIB Email: [email protected] The Wharf Telephone: 01332 253300 Stores Road Fax: 01332 253301 Derby UK Website: www.gov.uk/raib DE21 4BA This report is published by the Rail Accident Investigation Branch, Department for Transport. Cover image credits: Top: image taken from RAIB report 05/2016: Derailment at Godmersham. Second from top: image taken from RAIB report 09/2016: Runaway and collision at Bryn station. Third from top: image taken from RAIB report 11/2016: Derailment of a freight train near Langworth (image courtesy of Network Rail). Fourth from top: image taken from RAIB report 04/2017: Collision between a train and a tractor at Hockham Road user worked crossing. This page is intentionally left blank 4 Preface This is the Rail Accident Investigation Branch’s (RAIB) Annual Report for the calendar year 2016. -

02-120. Electric Multiple Units, Trains 9351 and 3647, Collision

R A I L W A Y O C C U R R E N C E R E P O R T 02-120 electric multiple units, Trains 9351 and 3647, collision, 31 August 2002 Wellington TRANSPORT ACCIDENT INVESTIGATION COMMISSION NEW ZEALAND The Transport Accident Investigation Commission is an independent Crown entity established to determine the circumstances and causes of accidents and incidents with a view to avoiding similar occurrences in the future. Accordingly it is inappropriate that reports should be used to assign fault or blame or determine liability, since neither the investigation nor the reporting process has been undertaken for that purpose. The Commission may make recommendations to improve transport safety. The cost of implementing any recommendation must always be balanced against its benefits. Such analysis is a matter for the regulator and the industry. These reports may be reprinted in whole or in part without charge, providing acknowledgement is made to the Transport Accident Investigation Commission. Report 02-120 electric multiple units Trains 9351 and 3647 collision Wellington 31 August 2002 Abstract On Saturday 31 August 2002 at about 1515, Train 9351, a Tranz Metro1 Johnsonville to Wellington electric multiple unit passenger service collided with Train 3647, a Tranz Metro Upper Hutt to Wellington electric multiple unit passenger service, as both trains were approaching the Wellington platforms on converging tracks. There were no injuries to passengers or crew and only minor damage to the trains. The safety issues identified included the well-being of the electric multiple unit driver of Train 9351 and his resulting capacity to recognise and respond to a danger signal indication. -

Rail Safety Report 2019-2020

19 20 OFFICE OF THE NATIONAL RAIL SAFETY REGULATOR Level 1, 75 Hindmarsh Square Adelaide SA 5000 PO Box 3461, Rundle Mall Adelaide SA 5000 Phone 08 8406 1500 Email [email protected] Web onrsr.com.au ISSN: 2204 - 2571 Copyright information © 2020 Office of the National Rail Safety Regulator RAIL SAFETY REPORT This material may be reproduced in whole or in part, provided the meaning is unchanged and the source is acknowledged. 2019-2020 Contents The Regulator’s Message 2 Introduction 5 About the Office of the National Rail Safety Regulator 6 About This Report 9 ONRSR 2019–2020 - At a glance 10 Rail Safety Statistical Summary 13 Railway-Related Fatalities 15 Railway-Related Serious Injuries 21 Passenger Train Derailments 26 Tram Derailments 29 Freight Train Derailments 31 Train Collisions 34 Tram Collisions 37 Signals Passed at Danger and Authorities Exceeded 40 Train Fires 42 Other Noteworthy Occurrences 44 National Priorities 47 National Priorities 2019–2020 - At a glance 48 Level Crossing Safety 51 Track Worker Safety 57 Contractor Management 60 Control Assurance 61 Data-Driven Intelligence 63 Safety Themes 65 Data Sharing 67 Appendix A: Network Statistics 72 Appendix B: Scope and Methods 74 the regulator’s message I DON’T THINK IT IS AN OVERSTATEMENT TO SUGGEST THE WORLD HAS BECOME A MORE COMPLICATED PLACE IN THE LAST 12 MONTHS. AT THE RISK OF SOUNDING SOMEWHAT CLICHÉD, THE NEED TO LOOK AFTER OURSELVES AND EACH OTHER REALLY IS MORE IMPORTANT THAN EVER. Never losing sight of why we are here and having genuine clarity of purpose has been The report also charts the progress we, as a regulator, and industry integral to the Office of the National Rail Safety Regulator’s (ONRSR) response to the collectively have made on our national priority issues – track worker safety, emergence of COVID-19. -

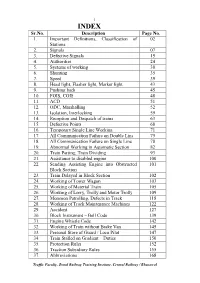

Sr.No. Description Page No. 1. Important Definitions, Classification of 02 Stations 2

1 INDEX Sr.No. Description Page No. 1. Important Definitions, Classification of 02 Stations 2. Signals 07 3. Defective Signals 15 4. Authorities 24 5. Systems of working 30 6. Shunting 35 7. Speed 39 8. Head light, Flasher light, Marker light 43 9. Pushing back 45 10. FOIS, COIS 48 11. ACD 51 12. ODC, Marshalling 52 13. Isolation, Interlocking 59 14. Reception and Despatch of trains 63 15. Defective Points 68 16. Temporary Single Line Working 71 17. All Communication Failure on Double Line 75 18. All Communication Failure on Single Line 78 19. Abnormal Working in Automatic Section 82 20. Train Parting, Train Dividing 93 21. Assistance to disabled engine 100 22. Sending Assisting Engine into Obstructed 101 Block Section 23. Train Delayed in Block Section 102 24. Working of Tower Wagon 103 25. Working of Material Train 105 26. Working of Lorry, Trolly and Motor Trolly 109 27. Monsoon Patrolling, Defects in Track 118 28. Working of Track Maintenance Machines 122 29. Accident 127 30. Block Instrument – Bell Code 139 31. Engine Whistle Code 142 32. Working of Train without Brake Van 145 33. Personal Store of Guard / Loco Pilot 147 34. Train Stalled on Gradient – Duties 150 35. Protection Rules 152 36. Traction Subsidiary Rules 155 37. Abbreviations 168 Traffic Faculty, Zonal Railway Training Institute, Central Railway / Bhusawal 2 Important Definitions 1. Adequate Distance: G.R.1.02 (2) – It means the distance sufficient to ensure safety. a) Block Over-lap – The distance sufficient to ensure safety for granting line clear. It shall be not less than 400 meters in TALQ signalling system and not less than 180 meters in MAUQ / MACLS signalling system. -

The Southall Rail Accident Inquiry Report Professor John Uff QC Freng

iealth 6 Safety Commission The Southall Rail Accident Inquiry Report - Professor John Uff QC FREng 2 Erratum The Southali Rail Accident Inquiry Report iSBN 0 7176 1757 2 Annex 09 Passengers & Staff believed to have sustained injury as a result of the accident Include 'Stuttard, Janis, Mrs Coach H' Delete ' Stothart, Chloe Helen, Miss Coach C' MlSC 210 HSE BOOKS 0 Crown copyright 2000 Applications for reproduction should be made in writing to: Copyright Unit, Her Majesty's Stationery Office, St Clernents House, 2-16 Colegate, Nofwich NR3 1BQ First published 2000 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the copyright owner. LIST OF CONTENTS Inquiry into Southall Railway Accident Preface Glossary Report Summary PART ONE THE ACCIDENT Chapter l How the accident happened Chapter 2 The emergency response Chapter 3 The track and signals Chapter 4 Why was the freight train crossing? Chapter 5 Driver competence and training Chapter 6 Why were the safety systems not working? Chapter 7 Why the accident happened PART TWO EVENTS SINCE SOUTJULL Chapter 8 The Inquiry and delay to progress Chapter 9 Reactions to Southall Chapter 10 Ladbroke Grove and its aftermath PART THREE WIDER SAFETY ISSUES Chapter 11 Crashworthiness and means of escape Chapter 12 Automatic Warning System (AWS) Chapter 13 Automatic Train Protection (ATP) Chapter 14 Railway Safety Issues PART FOUR CONCLUSION Chapter 15 Discussion and Conclusions Chapter 16 Lessons to be learned Chapter 17 Recommendations ANNEXES THIS Report follows an Inquiry held between September and December 1999 into the cause of a major rail accident which occurred on 19 September 1997 at Southall, 9 miles west of Paddington. -

A Railway Collision Avoidance System Exploiting Ad-Hoc Inter-Vehicle Communications and Galileo

A RAILWAY COLLISION AVOIDANCE SYSTEM EXPLOITING AD-HOC INTER-VEHICLE COMMUNICATIONS AND GALILEO Thomas Strang(1), Michael Meyer zu Hörste(2), Xiaogang Gu (3) German Aerospace Center (1)Institute of Communications and Navigation (2)Institute of Transportation Systems [email protected] [email protected] (3)Bombardier Transportation RailControlSolutions [email protected] ABSTRACT The introduction of the European global navigation satellite system GALILEO allows also for a modernization of automatic train control technology. This is advisable because of the still enormous amount of collisions between trains or other kinds of obstacles (construction vehicles, construction workers, pedestrians), even if comprehensive and complex technology is extensively deployed in the infrastructure which should help to avoid such collisions. Experiences from the aeronautical Traffic Alert and Collision Avoidance System (TCAS) as well as the maritime Automatic Identification System (AIS) have shown that the probability of collisions can be significantly reduced with collision avoidance support systems, which do hardly require infrastructure components. In this article, we introduce our “RCAS” approach consisting only of mobile ad-hoc components, i.e. without the necessity of extensions of the railway infrastructure. Each train determines its position, direction and speed using GALILEO and broadcasts this information, complemented with other important information such as dangerous goods classifications in the region of its current location. This information can be received and evaluated by other trains, which may – if a potential collision is detected – lead to traffic alerts and resolution advisories up to direct interventions (usually applying the brakes). STATE OF THE ART IN TRAIN CONTROL Today the safety of railway operation is mainly ensured by the interlocking which sets and locks the train route. -

Signal Passed at Danger by Track Machine Consist 8M71, Goobang Junction, 10 May 2009 I OTSI Rail Safety Investigation

RAIL SAFETY INVESTIGATION REPORT SIGNAL PASSED AT DANGER BY TRACK MACHINE CONSIST 8M71 GOOBANG JUNCTION 10 MAY 2009 RAIL SAFETY INVESTIGATION REPORT SIGNAL PASSED AT DANGER BY TRACK MACHINE CONSIST 8M71 GOOBANG JUNCTION 10 MAY 2009 Released under the provisions of Section 45C (2) of the Transport Administration Act 1988 and Section 67 (2) of the Rail Safety Act 2008 Investigation Reference 04439 Published by: The Office of Transport Safety Investigations Postal address: PO Box A2616, Sydney South, NSW 1235 Office location: Level 17, 201 Elizabeth Street, Sydney NSW 2000 Telephone: 02 9322 9200 Accident and incident notification: 1800 677 766 Facsimile: 02 9322 9299 E-mail: [email protected] Internet: www.otsi.nsw.gov.au This Report is Copyright. In the interests of enhancing the value of the information contained in this Report, its contents may be copied, downloaded, displayed, printed, reproduced and distributed, but only in unaltered form (and retaining this notice). However, copyright in material contained in this Report which has been obtained by the Office of Transport Safety Investigations from other agencies, private individuals or organisations, belongs to those agencies, individuals or organisations. Where use of their material is sought, a direct approach will need to be made to the owning agencies, individuals or organisations. Subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968, no other use may be made of the material in this Report unless permission of the Office of Transport Safety Investigations has been obtained. THE OFFICE OF TRANSPORT SAFETY INVESTIGATIONS The Office of Transport Safety Investigations (OTSI) is an independent NSW agency whose purpose is to improve transport safety through the investigation of accidents and incidents in the rail, bus and ferry industries. -

Definitions 1 2 Safety Rules 7 3 Fixed Signal 10 4 Conditions for Taking

S.No CHAPTER Page 1 Basic Concepts – Definitions 1 2 Safety Rules 7 3 Fixed Signal 10 4 Conditions for taking ‘off’ Signals 20 5 Classification of Stations 21 6 Minimum Equipment of Signals 22 7 Catch Siding & Slip Siding 23 8 Hand Signals 24 9 Fog Signal 28 10 Warning Signal 32 11 Boards 33 12 Indicators 37 13 Signal Failures 40 14 System of Working 54 15 Essentials of Absolute Block System 55 16 Various Authorities to Proceed - Table 56 17 Line Clear Ticket 58 18 ATP without Line Clear 59 19 Sending Relief Engine / Train into obstructed Block Section 61 20 T.I.C on Single line 63 21 T.I.C on Double line 65 22 Single line working on Double line 67 23 Train Dividing 69 24 Train Parting 71 25 Shunting 73 26 Securing of Vehicles 79 27 Protection Rules 81 28 Train held up at FSS 85 29 Train held up in Block Section 85 30 Engine Pushing 87 31 Goods Train without Guard / BV / Guard & BV 88 32 Isolation 90 33 Interlocking 92 34 Speeds, Speed over Facing Points, WTT 94 35 Engine & Train Lights 97 36 Caution Order 100 37 Line Block 106 38 Works of Short duration 108 39 Works of Long duration 109 40 Banner Flag, Engineering Indicators 110 S.No CHAPTER Page 41 Material Train 112 42 Cause Way 115 43 Patrolling 116 44 Train Papers – CTR, VG, RJB 117 45 Road learning 118 46 Equipments of LP/ALP 119 47 Riding on Engine / EMU, Manning an Engine 120 48 LP not to leave Engine while on duty 121 49 Driving Electric Engine / EMU 121 50 Fouling Mark not cleared 122 51 Good Home Taken ‘off’ for Passenger Train 122 52 Duties of LP before starting a Train 123 53 Attracting attention of LP 123 54 Unable to control the Train 124 55 Whistle Codes & Bell Codes 124 56 Electrified Section 126 57 Automatic Block System 131 58 Accident Manual 149 59 Marshalling Order 167 60 Long Haul Trains 172 61 Anemometer 173 62 LC Gates 174 63 Crew Management System 176 64 Sighting Committee 177 65 FOIS 178 66 ICMS 179 BASIC CONCEPTS 1) What are the Special features of Railways compared to other Transport system? i) Track Bound: a) Train is „Track Bound‟; it can move only along a fixed path made for it. -

Rail Safety Report 2018-2019

2018– 2019 Rail Safety Report Safe Railways for Australia Contents // 2018-2019 Contents The Regulator’s Message 2 Introduction 5 > About the Office of the National Rail Safety Regulator 6 > About This Report 9 > ONRSR 2018–2019 – At a Glance 10 Rail Safety Statistical Summary 13 Railway-Related Fatality 14 Railway-Related Serious Injury 18 Passenger Train Derailment 20 Freight Train Derailment 21 Collision Between Trains and with Rolling Stock 23 Signal Passed at Danger / Authority Exceeded 24 Other Noteworthy Occurrences 24 Incident Response 25 National Priorities 27 Level Crossing Safety 28 Track Worker Safety 32 Tourist and Heritage Sector, Safety Management Capability 35 Road Rail Vehicle Safety 37 National Priorities for 2020 39 Data-Driven Intelligence 43 Appendix: Scope and Methods 47 Safe Railways for Australia 1 Rail Safety Report // 2018-2019 Introduction // The Regulator’s Message The Regulator’s Message IN ALL OF LIFE’S PURSUITS, BE THEY PROFESSIONAL OR PERSONAL, THOSE THAT STAND STILL INVARIABLY SEE THE MOST IMPORTANT OPPORTUNITIES PASS THEM BY. For individuals and organisations alike knowing when to be proactive, reactive, Unfortunately accidents still happen and while the adaptable and flexible are skills that often underpin a successful approach. safety performance of the Australian rail industry was again strong through 2018–2019, the following And they are of course particularly relevant to something as important as keeping report still documents a range of occurrences that provide people safe. invaluable opportunities for all operators to contemplate ... this year we The Office of the National Rail Safety Regulator’s (ONRSR) Rail Safety Report 2018– their specific circumstances and make their own positive 2019 is a demonstration of our own desire to be nimble in conducting the business of changes as they set about learning lessons and perfecting bring you the most safety regulation. -

The Ladbroke Grove Rail Inquiry

The Ladbroke Grove Rail Inquiry Part 1 Report The Rt Hon Lord Cullen PC The Ladbroke Grove Rail Inquiry Part 1 Report The Rt Hon Lord Cullen PC © Crown copyright 2000 Applications for reproduction should be made in writing to: Copyright Unit, Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, St Clements House, 2-16 Colegate, Norwich NR3 1BQ First published 2001 ISBN 0 7176 2056 5 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the copyright owner. Front cover: View of crash site taken shortly after midday on 5 October 1999 ii Those who lost their lives Ladbroke Grove, 5 October 1999 Charlotte Andersen Derek Antonowitz Anthony Beeton Ola Bratlie Roger Brown Jennifer Carmichael Brian Cooper Robert Cotton Sam Di Lieto Shaun Donoghue Neil Dowse Cyril Elliott Fiona Grey Juliet Groves Sun Yoon Hah Michael Hodder Elaine Kellow Martin King Antonio Lacovara Rasak Ladipo Matthew Macaulay Delroy Manning John Northcott John Raisin David Roberts Allan Stewart Khawar Tauheed Muthulingam Thayaparan Andrew Thompson Bryan Tompson Simon Wood iii iv Contents List of plates vii Acknowledgements viii Chapters 1 Executive summary 1 2 The Inquiry 7 3 The journey before the crash 13 4 The crash 19 5 The actions of driver Hodder 51 6 The actions of the signallers 83 7 Railtrack and the infrastructure 103 8 Thames Trains and Automatic Train Protection 143 9 Thames Trains and driver management -

Signal 161 Passed at Danger Transadelaide Passenger Trainh307

ATSB TRANSPORT SAFETY INVESTIGATION REPORT Rail Occurrence Investigation 2006/003 Final Signal 161 Passed at Danger TransAdelaide Passenger Train H307 Adelaide, South Australia 28 March 2006 Published by: Australian Transport Safety Bureau Postal address: PO Box 967, Civic Square ACT 2608 Office location: 15 Mort Street, Canberra City, Australian Capital Territory Telephone: 1800 621 372; from overseas + 61 2 6274 6590 Accident and serious incident notification: 1800 011 034 (24 hours) Facsimile: 02 6274 6474; from overseas + 61 2 6274 6474 E-mail: [email protected] Internet: www.atsb.gov.au © Commonwealth of Australia 2007. This work is copyright. In the interests of enhancing the value of the information contained in this publication you may copy, download, display, print, reproduce and distribute this material in unaltered form (retaining this notice). However, copyright in the material obtained from other agencies, private individuals or organisations, belongs to those agencies, individuals or organisations. Where you want to use their material you will need to contact them directly. Subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968, you must not make any other use of the material in this publication unless you have the permission of the Australian Transport Safety Bureau. Please direct requests for further information or authorisation to: Commonwealth Copyright Administration, Copyright Law Branch Attorney-General’s Department, Robert Garran Offices, National Circuit, Barton ACT 2600 www.ag.gov.au/cca # ISBN and formal report -

Signals Passed at Danger by Train 1240 Marshall Near Geelong, Victoria on 29 May 2015

InsertSignals documentPassed at Danger title by Train 1240 LocationMarshall |near Date Geelong, Victoria | 29 May 2015 ATSB Transport Safety Report Investigation [InsertRail Occurrence Mode] Occurrence Investigation Investigation XX-YYYY-####RO-2015-009 Final – 12 December 2016 This investigation was conducted under the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003 by the Chief Investigator, Transport Safety (Victoria) on behalf of the Australian Transport Safety Bureau in accordance with the Collaboration Agreement entered into on 18 January 2013. Released in accordance with section 25 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003. Publishing information Published by: Australian Transport Safety Bureau Postal address: PO Box 967, Civic Square ACT 2608 Office: 62 Northbourne Avenue Canberra, Australian Capital Territory 2601 Telephone: 1800 020 616, from overseas +61 2 6257 4150 (24 hours) Accident and incident notification: 1800 011 034 (24 hours) Facsimile: 02 6247 3117, from overseas +61 2 6247 3117 Email: [email protected] Internet: www.atsb.gov.au © Commonwealth of Australia 2016 Ownership of intellectual property rights in this publication Unless otherwise noted, copyright (and any other intellectual property rights, if any) in this publication is owned by the Commonwealth of Australia. Creative Commons licence With the exception of the Coat of Arms, ATSB logo, and photos and graphics in which a third party holds copyright, this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence is a standard form license agreement that allows you to copy, distribute, transmit and adapt this publication provided that you attribute the work. The ATSB’s preference is that you attribute this publication (and any material sourced from it) using the following wording: Source: Australian Transport Safety Bureau.