XVI. Moving on 2005-2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2015 Full Program (PDF)

2015 Women in Dance Leadership Conference! ! October 29 - November 1, 2015! ! Manship Theatre, Baton Rouge, Louisiana, USA! ! Conference Director - Sandra Shih Parks WOMEN IN DANCE LEADERSHIP CONFERENCE 10/29/2015 - 11/1/2015 "1 Women in Dance Leadership Conference ! Mission Statement ! ! To investigate, explore, and reflect on women’s leadership by representing innovative and multicultural dance work to celebrate, develop, and promote women’s leadership in dance making, dance related fields, and other! male-dominated professions.! Conference Overview! ! DATE MORNING AFTERNOON EVENING Thursday 10/29/2015 !Registration/Check In! !Reception! Opening Talk -! Kim Jones/Yin Mei Karole Armitage and guests Performance Friday 10/30/2015 Speech - Susan Foster! Panel Discussions! Selected ! ! Choreographers’ Speech - Ann Dils !Master Classes! Concert Paper Presentations Saturday 10/31/2015 Speech - Dima Ghawi! Panel Discussions! ODC Dance Company ! ! ! Performance Speech - Meredith Master Classes! Warner! ! ! Ambassadors of Women Master Classes in Dance Showcase Sunday 11/1/2015 Master Class THODOS Dance Chicago Performance ! ! ! ! WOMEN IN DANCE LEADERSHIP CONFERENCE 10/29/2015 - 11/1/2015 "2 October 29th 2015! !Location 12 - 4 PM 4:30 PM - 6 PM 6 PM - 7:30 PM 8 PM - 9:30 PM !Main Theatre Kim Jones, Yin Mei ! and guests ! performance ! !Hartley/Vey ! Opening Talk by! !Studio Theatre Karole Armitage !Harley/Vey! !Workshop Theatre !Josef Sternberg ! Conference Room Jones Walker Foyer Registration! ! Conference Check In Reception Program Information! -

Post-9/11 Brown and the Politics of Intercultural Improvisation A

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE “Sound Come-Unity”: Post-9/11 Brown and the Politics of Intercultural Improvisation A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music by Dhirendra Mikhail Panikker September 2019 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Deborah Wong, Chairperson Dr. Robin D.G. Kelley Dr. René T.A. Lysloff Dr. Liz Przybylski Copyright by Dhirendra Mikhail Panikker 2019 The Dissertation of Dhirendra Mikhail Panikker is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgments Writing can feel like a solitary pursuit. It is a form of intellectual labor that demands individual willpower and sheer mental grit. But like improvisation, it is also a fundamentally social act. Writing this dissertation has been a collaborative process emerging through countless interactions across musical, academic, and familial circles. This work exceeds my role as individual author. It is the creative product of many voices. First and foremost, I want to thank my advisor, Professor Deborah Wong. I can’t possibly express how much she has done for me. Deborah has helped deepen my critical and ethnographic chops through thoughtful guidance and collaborative study. She models the kind of engaged and political work we all should be doing as scholars. But it all of the unseen moments of selfless labor that defines her commitment as a mentor: countless letters of recommendations, conference paper coachings, last minute grant reminders. Deborah’s voice can be found across every page. I am indebted to the musicians without whom my dissertation would not be possible. Priya Gopal, Vijay Iyer, Amir ElSaffar, and Hafez Modirzadeh gave so much of their time and energy to this project. -

UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title "Sound Come-Unity": Post-9/11 Brown and the Politics of Intercultural Improvisation Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1pb3108j Author Panikker, Dhirendra Mikhail Publication Date 2019 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE “Sound Come-Unity”: Post-9/11 Brown and the Politics of Intercultural Improvisation A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music by Dhirendra Mikhail Panikker September 2019 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Deborah Wong, Chairperson Dr. Robin D.G. Kelley Dr. René T.A. Lysloff Dr. Liz Przybylski Copyright by Dhirendra Mikhail Panikker 2019 The Dissertation of Dhirendra Mikhail Panikker is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgments Writing can feel like a solitary pursuit. It is a form of intellectual labor that demands individual willpower and sheer mental grit. But like improvisation, it is also a fundamentally social act. Writing this dissertation has been a collaborative process emerging through countless interactions across musical, academic, and familial circles. This work exceeds my role as individual author. It is the creative product of many voices. First and foremost, I want to thank my advisor, Professor Deborah Wong. I can’t possibly express how much she has done for me. Deborah has helped deepen my critical and ethnographic chops through thoughtful guidance and collaborative study. She models the kind of engaged and political work we all should be doing as scholars. But it all of the unseen moments of selfless labor that defines her commitment as a mentor: countless letters of recommendations, conference paper coachings, last minute grant reminders. -

CDSQ Fall 2015

One of the most unique and sought-after chamber ensembles on the concert stage today, the Carpe Diem String Quartet is a boundary-breaking ensemble that has earned widespread critical and audience acclaim for its innovative programming and electrifying performances. Carpe Diem defies easy classification with programming that includes classical, Gypsy, tango, folk, pop, rock, and jazz-inspired music. The quartet appears on traditional concert series (Jordan Hall, Boston MA, National Gallery of Art, Washington DC; Chautauqua Institute, Chautauqua NY; Asolo Theater, Sarasota FL) as well as unconventional venues (Poisson Rouge, NYC; Bach Dancing and Dynamite Society, Half-Moon Bay, CA; The Redlands Bowl, Redlands, CA; The Mug & Brush, Columbus, OH). Carpe Diem has been awarded four transformative grants from the PNC Foundation for their community outreach in Central Ohio. Carpe Diem has become one of America's premiere “indie” string quartets without sacrificing its commitment to the traditional quartet repertoire, and continues to rack up accolades and awards: “Here [Carpe Diem] once again triumphs…with readings that marry cantabile espressivo and tendency towards Beethovenian cross- referencing to memorable effect…The Carpe Diem players perform this music with the same devoted intensity as if they were rediscovering a lost work by Tchaikovsky…The players here communicate such delight in the Russian’s quirky inspiration that the ear is led effortlessly on…Well worth investigating.” (The Strad) “Carpe Diem’s performance of Beethoven’s Op.59 -

Make It New: Reshaping Jazz in the 21St Century

Make It New RESHAPING JAZZ IN THE 21ST CENTURY Bill Beuttler Copyright © 2019 by Bill Beuttler Lever Press (leverpress.org) is a publisher of pathbreaking scholarship. Supported by a consortium of liberal arts institutions focused on, and renowned for, excellence in both research and teaching, our press is grounded on three essential commitments: to be a digitally native press, to be a peer- reviewed, open access press that charges no fees to either authors or their institutions, and to be a press aligned with the ethos and mission of liberal arts colleges. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc-nd/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, California, 94042, USA. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.11469938 Print ISBN: 978-1-64315-005- 5 Open access ISBN: 978-1-64315-006- 2 Library of Congress Control Number: 2019944840 Published in the United States of America by Lever Press, in partnership with Amherst College Press and Michigan Publishing Contents Member Institution Acknowledgments xi Introduction 1 1. Jason Moran 21 2. Vijay Iyer 53 3. Rudresh Mahanthappa 93 4. The Bad Plus 117 5. Miguel Zenón 155 6. Anat Cohen 181 7. Robert Glasper 203 8. Esperanza Spalding 231 Epilogue 259 Interview Sources 271 Notes 277 Acknowledgments 291 Member Institution Acknowledgments Lever Press is a joint venture. This work was made possible by the generous sup- port of -

2017 Guild Hall Summer Season

2017 GUILD HALL SUMMER SEASON Avedon’s America Exhibition: Aug 12–Oct 9, 2017 Donyale Luna, dress and sandals by Paco Rabanne, New York, December 6,1966 Gelatin silver print, 72 x 30 inches © The Richard Avedon Foundation see hamptons real estate from a fresh perspective #WhyWeLiveHere Ed Bruehl Licensed Associate Real Estate Broker Cell: (646) 752-1233 [email protected] saunders.com | hamptonsrealestate.com /SaundersAssociates /SaundersRE /SaundersRE /HamptonsRealEstate /SaundersAssociates /SaundersRE EdBruehl.com 14 main street, southampton village, new york (631) 283-5050 2287 montauk highway, bridgehampton, new york (631) 537-5454 26 montauk highway, east hampton, new york (631) 324-7575 buy | sell | rent | invest “Saunders, A Higher Form of Realty,” is registered in the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. Equal Housing Opportunity. see hamptons real estate from a fresh perspective #WhyWeLiveHere Ed Bruehl Licensed Associate Real Estate Broker Cell: (646) 752-1233 [email protected] saunders.com | hamptonsrealestate.com /SaundersAssociates /SaundersRE /SaundersRE /HamptonsRealEstate /SaundersAssociates /SaundersRE EdBruehl.com 14 main street, southampton village, new york (631) 283-5050 2287 montauk highway, bridgehampton, new york (631) 537-5454 26 montauk highway, east hampton, new york (631) 324-7575 buy | sell | rent | invest “Saunders, A Higher Form of Realty,” is registered in the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. Equal Housing Opportunity. Discover the most beautiful waterfront retirement community in New York. Chart your course. Own your future. Elegant apartments and homes. Sophisticated continuing care options. In Greenport on the Award-winning, Fitch-rated, Long Island Sound equity-based community. Schedule a tour, learn more 1500 Brecknock Call 631.593.8242 or Road, Greenport NY 11944 visit peconiclanding.org FROM BUSINESSES ON MAIN STREET TO YOUR FRIENDS DOWN THE STREET Working TOGETHER sets us apart. -

University of Alberta 'Indo-Jazz Fusion'

University of Alberta ‘Indo-Jazz Fusion’: Jazz and Karnatak Music in Contact by Tanya Kalmanovitch A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Music Edmonton, Alberta Spring 2008 Abstract An inherently intercultural music, jazz presents a unique entry in the catalog of interactions between Indian music and the west. This dissertation is situated in a line of recent accounts that reappraise the period of Western colonial hegemony in India by tracing a complex continuum of historical and musical events over three centuries. It charts the historical routes by which jazz and Karnatak music have come into contact in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, both in India and abroad. It presents a detailed account of the history of jazz in India, and Indian music in jazz, and examines jazz’s contact with Karnatak music in three contexts—jazz pedagogy, intercultural collaboration, and the Indian diaspora in the United States—illustrating the musical, social and performative spaces in which these musics come into contact, and describing the specific musical and social practices, and political and social institutions that support this activity. Case studies in this dissertation include an educational exchange between the Jazz and Contemporary Music Program of the New School University (New York, NY) and the Brhaddhvani Research and Training Centre for Musics of the World (Chennai, India), directed by the author in December 2003 – January 2004; a 2001 collaboration between Irish jazz/traditional band Khanda and the Karnataka College of Percussion; and analyses of recent recordings by pianist Vijay Iyer, saxophonist Rudresh Mahanthappa and drummer Ravish Momin. -

07/31/2017 Daily Program Listing II 06/14/2017 Page 1 of 123

Daily Program Listing II 43.1 Date: 06/14/2017 07/01/2017 - 07/31/2017 Page 1 of 123 Sat, Jul 01, 2017 Title Start Subtitle Distrib Stereo Cap AS2 Episode 00:00:01 NHK Newsline APTEX (S) (CC) N/A #8065 00:30:00 Global 3000 WNVC (S) (CC) N/A #925H Helping Islamic State Terror Group Victims In Iraq Thousands of women and children have been kidnapped and mistreated the so-called Islamic State terror group. A German psychotherapist is trying to help the victims. And fishermen in the Philippines are fighting to preserve dwindling fish stocks. 01:00:00 Song of the Mountains NETA (S) (CC) N/A #1120H Five Mile Mountain Road/Idle Time 02:00:00 Woodsongs NETA (S) (CC) N/A #1801H Jewel Jewel is a multi-platinum singer-songwriter, poet and actress. She has sold more than 25 million albums over her musical career. Her debut album Pieces of You had the hit "Who Will Save Your Soul". From the remote tundra of her Alaskan youth to the triumph of international stardom, the 41-year-old singer has always found a way to persevere and convey the emotional turmoil of life during it's most difficult and challenging moments through her work. Jewel tells the countless moments of introspection that led her here with her memoir Never Broken and new album Picking Up The Pieces. 03:00:00 Film School Shorts NETA (S) (CC) N/A #402H America '80s-inspired comedy Total Freak tells the story of how a boy's pursuit of his first summer camp kiss awakens a monster from the deep. -

Moran & Iyer Notes.Indd

Cal Performances Presents Saturday, November , , pm Wheeler Auditorium Jason Moran & Th e Bandwagon and Vijay Iyer Quartet Cal Performances’ – season is sponsored by Wells Fargo. 4 CAL PERFORMANCES About the Artists Jason Moran & The Bandwagon jazz label, such as Monk, Herbie Hancock and Herbie Nichols. Jason Moran, piano Moran’s debut recording as a leader, Tarus Mateen, bass Soundtrack to Human Motion, which found him Nasheet Waits, drums in the company of Osby, Harland, vibraphonist Stefon Harris and bassist Lonnie Plaxico, was Jason Moran was born in Houston, Texas in released in to great critical praise. (Ben . He began studying the piano at age six, Ratliff of Th e New York Times named it the best but longed to quit the instrument until he fi rst album of the year.) Th e following year’s Facing experienced the sounds of jazz legend Th elonious Left found Moran stripping down to a trio with Monk, an experience that renewed his interest in bassist Tarus Mateen and drummer Nasheet music and established an early role model in his Waits, and prompted JazzTimes to declare the creative development. album “an instant classic.” Moran augmented the Moran went on to attend Houston’s High trio for his third Blue Note release, Black Stars, School for the Performing and Visual Arts, adding avant-garde icon Sam Rivers, who plays where he became an active member of the jazz saxophone, fl ute and piano on the recording. program, playing in the big band and leading Gary Giddins of Th e Village Voice exclaimed, a jazz quartet. -

GUILD HALL 2018 SUMMER Nownow Isis Thethe Timetime Buybuy | | Sell Sell | | Rent Rent | | Invest Invest

GUILD HALL 2018 SUMMER nownow isis thethe timetime buybuy | | sell sell | | rent rent | | invest invest seesee hamptonshamptons realreal estateestate fromfrom aa freshfresh perspectiveperspective #WhyWeLiveHere#WhyWeLiveHere EdEd Bruehl Bruehl LicensedLicensed Associate Associate Real Real Estate Estate Broker Broker Cell:Cell: (646) (646) 752-1233 752-1233 [email protected]@Saunders.com EdBruehl.comEdBruehl.com saunders.comsaunders.com | | hamptonsrealestate.com hamptonsrealestate.com /SaundersAssociates/SaundersAssociates /SaundersRE/SaundersRE /SaundersRE/SaundersRE /HamptonsRealEstate/HamptonsRealEstate /SaundersAssociates/SaundersAssociates 3333 sunset sunset avenue, avenue, westhampton westhampton beach beach (631) (631) 288-4800 288-4800 1414 main main street, street, southampton southampton village, village, new new york york (631) (631) 283-5050 283-5050 22872287 montauk montauk highway, highway, bridgehampton, bridgehampton, new new york york (631) (631) 537-5454 537-5454 2626 montauk montauk highway, highway, east east hampton, hampton, new new york york (631) (631) 324-7575 324-7575 “Saunders, “Saunders, A AHigher Higher Form Form of of Realty,” Realty,” is is registered registered in in the the U.S. U.S. Patent Patent and and Trademark Trademark Office. Office. Equal Equal Housing Housing Opportunity. Opportunity. FROM THE BIG APPLE TO YOUR HOME AT THE BEACH With an expanded branch network from Montauk to Manhattan, count on BNB Bank whether you’re growing your business in the city . or putting down roots on the East End. Partner with BNB on your next residential mortgage. To get started call Beth Flanagan Hard at 631.537.1000, Ext. 7472, NMLS # 408699. GARDEN SHOP NURSERY LANDSCAPE DESIGN, BUILD, AND MAINTAIN 631.537.3700 COMMUNITY BANKING FROM MONTAUK TO MANHATTAN 631.537.1000 I WWW.BNBBANK.COM I MEMBER FDIC Live Better.. -

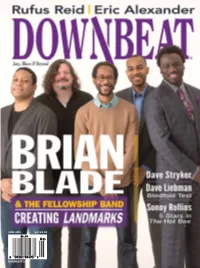

Downbeat.Com June 2014 U.K. £3.50

JUNE 2014 U.K. £3.50 DOWNBEAT.COM JUNE 2014 VOLUME 81 / NUMBER 6 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Associate Editor Davis Inman Contributing Editors Ed Enright Kathleen Costanza Art Director LoriAnne Nelson Contributing Designer Ara Tirado Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Sue Mahal Circulation Assistant Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Pete Fenech 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. Jackson, Jimmy Katz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Richard Seidel, Tom -

Rudolf Serkin Papers Ms

Rudolf Serkin papers Ms. Coll. 813 Finding aid prepared by Ben Rosen and Juliette Appold. Last updated on April 03, 2017. University of Pennsylvania, Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts 2015 June 26 Rudolf Serkin papers Table of Contents Summary Information....................................................................................................................................3 Biography/History..........................................................................................................................................4 Scope and Contents....................................................................................................................................... 6 Administrative Information........................................................................................................................... 6 Related Materials........................................................................................................................................... 7 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................7 Collection Inventory...................................................................................................................................... 9 I. Correspondence.................................................................................................................................... 9 II. Performances...................................................................................................................................274