Draft Recovery Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Palm Haven Garden Plant List - 2010

PALM HAVEN GARDEN PLANT LIST - 2010 BOTANICAL NAME COMMON NAME Achillea millefolium 'Paprika' Paprika yarrow Arctostaphylos glauca big berry manzanita Arctostaphylos pajaroensis Pajaro manzanita Arctostaphylos uva-ursi bearberry Arctostaphylos uva-ursi 'San Bruno Mountain' San Bruno Mountain bearberry Aristolochia californica California pipevine Artemisia pycnocephala coastal sagewort Baccharis pilularis 'Twin Peaks' Twin Peaks dwarf coyote brush Berberis aquifolium 'Golden Abundance' Golden Abundance Oregon-grape Carex spissa San Diego sedge Ceanothus 'Joyce Coulter' Joyce Coulte wild lilac Ceanothus arboreus feltleaf ceanothus Ceanothus gloriosus var exaltatus 'Emily Brown' Emily Brown glory brush Dendromecon harfordii Channel Island tree poppy Epilobium canum California fuchsia Erigeron glaucus seaside daisy Eriogonum fasciculatum California buckwheat Eriogonum latifolium coast buckwheat Eriogonum umbellatum sulfur flower Eriophyllum confertiflorum golden yarrow Heteromeles arbutifolia toyon Heterotheca sessilifolora false goldenaster Iris douglasiana Douglas iris Leymus condensatus 'Canyon Prince' Canyon Prince giant wild rye Mimulus aurantiacus sticky monkeyflower Monardella villosa coyote mint Mulhenbergia rigens deer grass Penstemon heterophyllus foothill penstemon Physocarpus capitatus ninebark Rhamnus californica 'Ed Holm' Ed Holm coffeeberry Rhamnus californica 'Mound San Bruno' Mound San Bruno coffeeberry Salvia clevelandii Cleveland sage Salvia mellifera 'Shirley's Creeper' Shirley's Creepe sage Salvia sonomensis 'Bee's Bliss' Bee's Bliss sage Satureja douglasii yerba buena Trichostema lanatum wolly blue curls Typha angustifolia narrow-leaved cattail Verbena lilacina lilac verbena Vitis californica 'Roger's Red' Roger's Red California wild grape. -

The 2014 Golden Gate National Parks Bioblitz - Data Management and the Event Species List Achieving a Quality Dataset from a Large Scale Event

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science The 2014 Golden Gate National Parks BioBlitz - Data Management and the Event Species List Achieving a Quality Dataset from a Large Scale Event Natural Resource Report NPS/GOGA/NRR—2016/1147 ON THIS PAGE Photograph of BioBlitz participants conducting data entry into iNaturalist. Photograph courtesy of the National Park Service. ON THE COVER Photograph of BioBlitz participants collecting aquatic species data in the Presidio of San Francisco. Photograph courtesy of National Park Service. The 2014 Golden Gate National Parks BioBlitz - Data Management and the Event Species List Achieving a Quality Dataset from a Large Scale Event Natural Resource Report NPS/GOGA/NRR—2016/1147 Elizabeth Edson1, Michelle O’Herron1, Alison Forrestel2, Daniel George3 1Golden Gate Parks Conservancy Building 201 Fort Mason San Francisco, CA 94129 2National Park Service. Golden Gate National Recreation Area Fort Cronkhite, Bldg. 1061 Sausalito, CA 94965 3National Park Service. San Francisco Bay Area Network Inventory & Monitoring Program Manager Fort Cronkhite, Bldg. 1063 Sausalito, CA 94965 March 2016 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colorado, publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics. These reports are of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Report Series is used to disseminate comprehensive information and analysis about natural resources and related topics concerning lands managed by the National Park Service. -

Petition to List Mountain Lion As Threatened Or Endangered Species

BEFORE THE CALIFORNIA FISH AND GAME COMMISSION A Petition to List the Southern California/Central Coast Evolutionarily Significant Unit (ESU) of Mountain Lions as Threatened under the California Endangered Species Act (CESA) A Mountain Lion in the Verdugo Mountains with Glendale and Los Angeles in the background. Photo: NPS Center for Biological Diversity and the Mountain Lion Foundation June 25, 2019 Notice of Petition For action pursuant to Section 670.1, Title 14, California Code of Regulations (CCR) and Division 3, Chapter 1.5, Article 2 of the California Fish and Game Code (Sections 2070 et seq.) relating to listing and delisting endangered and threatened species of plants and animals. I. SPECIES BEING PETITIONED: Species Name: Mountain Lion (Puma concolor). Southern California/Central Coast Evolutionarily Significant Unit (ESU) II. RECOMMENDED ACTION: Listing as Threatened or Endangered The Center for Biological Diversity and the Mountain Lion Foundation submit this petition to list mountain lions (Puma concolor) in Southern and Central California as Threatened or Endangered pursuant to the California Endangered Species Act (California Fish and Game Code §§ 2050 et seq., “CESA”). This petition demonstrates that Southern and Central California mountain lions are eligible for and warrant listing under CESA based on the factors specified in the statute and implementing regulations. Specifically, petitioners request listing as Threatened an Evolutionarily Significant Unit (ESU) comprised of the following recognized mountain lion subpopulations: -

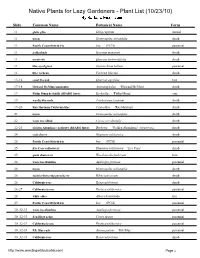

Native Plants for Lazy Gardeners - Plant List (10/23/10)

Native Plants for Lazy Gardeners - Plant List (10/23/10) Slide Common Name Botanical Name Form 11 globe gilia Gilia capitata annual 11 toyon Heteromeles arbutifolia shrub 11 Pacific Coast Hybrid iris Iris (PCH) perennial 11 goldenbush Isocoma menziesii shrub 11 scrub oak Quercus berberidifolia shrub 11 blue-eyed grass Sisyrinchium bellum perennial 11 lilac verbena Verbena lilacina shrub 13-16 coast live oak Quercus agrifolia tree 17-18 Howard McMinn man anita Arctostaphylos 'Howard McMinn' shrub 19 Philip Mun keckiella (RSABG Intro) Keckiella 'Philip Munz' ine 19 woolly bluecurls Trichostema lanatum shrub 19-20 Ray Hartman California lilac Ceanothus 'Ray Hartman' shrub 21 toyon Heteromeles arbutifolia shrub 22 western redbud Cercis occidentalis shrub 22-23 Golden Abundance barberry (RSABG Intro) Berberis 'Golden Abundance' (MAHONIA) shrub 2, coffeeberry Rhamnus californica shrub 25 Pacific Coast Hybrid iris Iris (PCH) perennial 25 Eve Case coffeeberry Rhamnus californica '. e Case' shrub 25 giant chain fern Woodwardia fimbriata fern 26 western columbine Aquilegia formosa perennial 26 toyon Heteromeles arbutifolia shrub 26 fuchsia-flowering gooseberry Ribes speciosum shrub 26 California rose Rosa californica shrub 26-27 California fescue Festuca californica perennial 28 white alder Alnus rhombifolia tree 29 Pacific Coast Hybrid iris Iris (PCH) perennial 30 032-33 western columbine Aquilegia formosa perennial 30 032-33 San Diego sedge Carex spissa perennial 30 032-33 California fescue Festuca californica perennial 30 032-33 Elk Blue rush Juncus patens '.l1 2lue' perennial 30 032-33 California rose Rosa californica shrub http://www weedingwildsuburbia com/ Page 1 30 032-3, toyon Heteromeles arbutifolia shrub 30 032-3, fuchsia-flowering gooseberry Ribes speciosum shrub 30 032-3, Claremont pink-flowering currant (RSA Intro) Ribes sanguineum ar. -

Late Cenozoic Tectonics of the Central and Southern Coast Ranges of California

OVERVIEW Late Cenozoic tectonics of the central and southern Coast Ranges of California Benjamin M. Page* Department of Geological and Environmental Sciences, Stanford University, Stanford, California 94305-2115 George A. Thompson† Department of Geophysics, Stanford University, Stanford, California 94305-2215 Robert G. Coleman Department of Geological and Environmental Sciences, Stanford University, Stanford, California 94305-2115 ABSTRACT within the Coast Ranges is ascribed in large Taliaferro (e.g., 1943). A prodigious amount of part to the well-established change in plate mo- geologic mapping by T. W. Dibblee, Jr., pre- The central and southern Coast Ranges tions at about 3.5 Ma. sented the areal geology in a form that made gen- of California coincide with the broad Pa- eral interpretations possible. E. H. Bailey, W. P. cific–North American plate boundary. The INTRODUCTION Irwin, D. L. Jones, M. C. Blake, and R. J. ranges formed during the transform regime, McLaughlin of the U.S. Geological Survey and but show little direct mechanical relation to The California Coast Ranges province encom- W. R. Dickinson are among many who have con- strike-slip faulting. After late Miocene defor- passes a system of elongate mountains and inter- tributed enormously to the present understanding mation, two recent generations of range build- vening valleys collectively extending southeast- of the Coast Ranges. Representative references ing occurred: (1) folding and thrusting, begin- ward from the latitude of Cape Mendocino (or by these and many other individuals were cited in ning ca. 3.5 Ma and increasing at 0.4 Ma, and beyond) to the Transverse Ranges. This paper Page (1981). -

Pinolecreeksedimentfinal

Pinole Creek Watershed Sediment Source Assessment January 2005 Prepared by the San Francisco Estuary Institute for USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service and Contra Costa Resource Conservation District San Francisco Estuary Institute The Regional Watershed Program was founded in 1998 to assist local and regional environmental management and the public to understand, characterize and manage environmental resources in the watersheds of the Bay Area. Our intent is to help develop a regional picture of watershed condition and downstream effects through a solid foundation of literature review and peer- review, and the application of a range of science methodologies, empirical data collection and interpretation in watersheds around the Bay Area. Over this time period, the Regional Watershed Program has worked with Bay Area local government bodies, universities, government research organizations, Resource Conservation Districts (RCDs) and local community and environmental groups in the Counties of Marin, Sonoma, Napa, Solano, Contra Costa, Alameda, Santa Clara, San Mateo, and San Francisco. We have also fulfilled technical advisory roles for groups doing similar work outside the Bay Area. This report should be referenced as: Pearce, S., McKee, L., and Shonkoff, S., 2005. Pinole Creek Watershed Sediment Source Assessment. A technical report of the Regional Watershed Program, San Francisco Estuary Institute (SFEI), Oakland, California. SFEI Contribution no. 316, 102 pp. ii San Francisco Estuary Institute ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The authors gratefully -

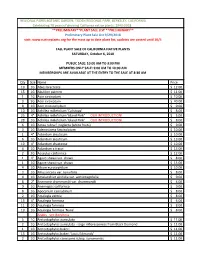

Qty Size Name Price 10 1G Abies Bracteata 12.00 $ 15 1G Abutilon

REGIONAL PARKS BOTANIC GARDEN, TILDEN REGIONAL PARK, BERKELEY, CALIFORNIA Celebrating 78 years of growing California native plants: 1940-2018 **PRELIMINARY**PLANT SALE LIST **PRELIMINARY** Preliminary Plant Sale List 9/29/2018 visit: www.nativeplants.org for the most up to date plant list, updates are posted until 10/5 FALL PLANT SALE OF CALIFORNIA NATIVE PLANTS SATURDAY, October 6, 2018 PUBLIC SALE: 10:00 AM TO 3:00 PM MEMBERS ONLY SALE: 9:00 AM TO 10:00 AM MEMBERSHIPS ARE AVAILABLE AT THE ENTRY TO THE SALE AT 8:30 AM Qty Size Name Price 10 1G Abies bracteata $ 12.00 15 1G Abutilon palmeri $ 11.00 1 1G Acer circinatum $ 10.00 3 5G Acer circinatum $ 40.00 8 1G Acer macrophyllum $ 9.00 10 1G Achillea millefolium 'Calistoga' $ 8.00 25 4" Achillea millefolium 'Island Pink' OUR INTRODUCTION! $ 5.00 28 1G Achillea millefolium 'Island Pink' OUR INTRODUCTION! $ 8.00 6 1G Actea rubra f. neglecta (white fruits) $ 9.00 3 1G Adenostoma fasciculatum $ 10.00 1 4" Adiantum aleuticum $ 10.00 6 1G Adiantum aleuticum $ 13.00 10 4" Adiantum shastense $ 10.00 4 1G Adiantum x tracyi $ 13.00 2 2G Aesculus californica $ 12.00 1 4" Agave shawii var. shawii $ 8.00 1 1G Agave shawii var. shawii $ 15.00 4 1G Allium eurotophilum $ 10.00 3 1G Alnus incana var. tenuifolia $ 8.00 4 1G Amelanchier alnifolia var. semiintegrifolia $ 9.00 8 2" Anemone drummondii var. drummondii $ 4.00 9 1G Anemopsis californica $ 9.00 8 1G Apocynum cannabinum $ 8.00 2 1G Aquilegia eximia $ 8.00 15 4" Aquilegia formosa $ 6.00 11 1G Aquilegia formosa $ 8.00 10 1G Aquilegia formosa 'Nana' $ 8.00 Arabis - see Boechera 5 1G Arctostaphylos auriculata $ 11.00 2 1G Arctostaphylos auriculata - large inflorescences from Black Diamond $ 11.00 1 1G Arctostaphylos bakeri $ 11.00 15 1G Arctostaphylos bakeri 'Louis Edmunds' $ 11.00 2 1G Arctostaphylos canescens subsp. -

3.4 Biological Resources for the Purpose of This EIR, Biological Resources Comprise Vegetation, Wildlife, Natural Communities, and Wetlands and Other Waters

Impact Analysis Alameda County Community Development Agency Biological Resources 3.4 Biological Resources For the purpose of this EIR, biological resources comprise vegetation, wildlife, natural communities, and wetlands and other waters. Potential biological resource impacts associated with the program and the two individual projects are analyzed. Potential impacts are described quantitatively and qualitatively in Section 3.4.2, Environmental Impacts. This section also identifies specific and detailed measures to avoid, minimize, or compensate for potentially significant impacts on biological resources, where necessary. 3.4.1 Existing Conditions Regulatory Setting Federal Endangered Species Act Pursuant to the federal Endangered Species Act (ESA), USFWS and the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) have authority over projects that may result in take of a species listed as threatened or endangered under the act. Take is defined under the ESA, in part, as killing, harming, or harassing. Under federal regulations, take is further defined to include habitat modification or degradation that results, or is reasonably expected to result, in death or injury to wildlife by significantly impairing essential behavioral patterns, including breeding, feeding, or sheltering. If a likelihood exists that a project would result in take of a federally listed species, either an incidental take permit, under Section 10(a) of the ESA, or a federal interagency consultation, under Section 7 of the ESA, is required. Several federally listed species—vernal pool fairy shrimp (Branchinecta lynchi), longhorn fairy shrimp (Branchinecta longiantenna), vernal pool tadpole shrimp (Lepidurus packardi), California tiger salamander (Ambystoma californiense), California red‐legged frog (Rana draytonii), Alameda whipsnake (Masticophis lateralis euryxanthus), and San Joaquin kit fox (Vulpes macrotis mutica)—have the potential to be affected by activities associated with the Golden Hills and Patterson Pass projects as well as subsequent repowering projects. -

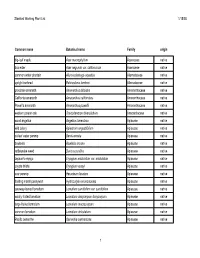

Rare Plant Species

Rare plant species of the upper Sausal Creek watershed Scientific Name Common Name Status Acer macrophyllum big-leaf maple rscw Acer negundo var.californicum box-elder LW Achillea millefolium yarrow rscw Actaea rubra baneberry LB Adenostema fasciculatum chamise rscw Adiantum aleuticum five-finger fern LA2 Adiantum jordanii California maidenhair rscw Alnus rhombifolia white alder rscw Alnus rubra red alder LA1 Amsinckia ssp. fiddleneck rscw Aralia californica elk-clover LB Arbutus menziesii Pacific madrone LB Arctostaphylos pallida pallid manzanita FT/SE Arctostaphylos tomentosa ssp. crustacea brittleleaf manzanita LB Asarum caudatum wild ginger LA2 Aster radulinus aster rscw Astragalus gambelianus rscw Berberis pinnata ssp. pinnata California barberry LW Brodiaea elegans ssp. elegans harvest brodiaea rscw Calochortus luteus yellow mariposa lily rscw Calochortus umbellatus Oakland star-tulip C4 Ceanothus oliganthus var. sorediatus jimbrush rscw Ceanothus thyrsiflorus blueblossom LB Cercocarpus betuloides var. betuloides mountain mahogany LW Chrysolepis chrysophylla var.minor golden chinquapin LA1 Cirsium occidentale var. venustum Venus thistle LW Clarkia rubicunda farewell-to-spring rscw Clematis lasiantha pipestems rscw Collinsia heterophylla chinese houses rscw Cornus sericea ssp. sericea American dogwood LA3 Cynoglossum grande hound's tongue LW Dichelostemma capitatum ssp. capitatum blue dicks rscw Dirca occidentalis western leatherwood C1B Disporum hookeri fairy bells LW Elymus multisetus big squirreltail rscw Epilobium canum ssp. canum california fuchsia rscw Eriogonum nudum var. auriculatum eared buckwheat LW Eriophyllum confertiflorum var. confertiflorum golden yarrow rscw Fritillaria affinis ssp. affinis checker lily rscw Galium triflorum sweet-scented bedstraw LA2 Garrya elliptica coast silk-tassle LW Gaultheria shallon salal LA1 Gilia achilleifolia ssp. multicaulis rscw Gnaphalium bicolor rscw Gnaphalium canescens ssp. -

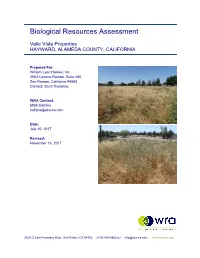

Biological Resources Assessment

Biological Resources Assessment Valle Vista Properties HAYWARD, ALAMEDA COUNTY, CALIFORNIA Prepared For: William Lyon Homes, Inc. 2603 Camino Ramon, Suite 450 San Ramon, California 94583 Contact: Scott Roylance WRA Contact: Mark Kalnins [email protected] Date: July 10, 2017 Revised: November 16, 2017 2169-G East Francisco Blvd., San Rafael, CA 94702 (415) 454-8868 tel [email protected] www.wra-ca.com This page intentionally blank. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................... 3 2.0 REGULATORY BACKGROUND ........................................................................................... 3 2.1 Sensitive Biological Communities .............................................................................. 3 2.2 Special-Status Species .............................................................................................. 8 2.3 Relevant Local Policies, Ordinances, Regulations ..................................................... 9 3.0 METHODS ............................................................................................................................. 9 3.1 Biological Communities ............................................................................................ 10 3.1.1 Non-Sensitive Biological Communities ...................................................... 10 3.1.2 Sensitive Biological Communities .............................................................. 10 3.2 Special-Status Species ........................................................................................... -

Plant List for Web Page

Stanford Working Plant List 1/15/08 Common name Botanical name Family origin big-leaf maple Acer macrophyllum Aceraceae native box elder Acer negundo var. californicum Aceraceae native common water plantain Alisma plantago-aquatica Alismataceae native upright burhead Echinodorus berteroi Alismataceae native prostrate amaranth Amaranthus blitoides Amaranthaceae native California amaranth Amaranthus californicus Amaranthaceae native Powell's amaranth Amaranthus powellii Amaranthaceae native western poison oak Toxicodendron diversilobum Anacardiaceae native wood angelica Angelica tomentosa Apiaceae native wild celery Apiastrum angustifolium Apiaceae native cutleaf water parsnip Berula erecta Apiaceae native bowlesia Bowlesia incana Apiaceae native rattlesnake weed Daucus pusillus Apiaceae native Jepson's eryngo Eryngium aristulatum var. aristulatum Apiaceae native coyote thistle Eryngium vaseyi Apiaceae native cow parsnip Heracleum lanatum Apiaceae native floating marsh pennywort Hydrocotyle ranunculoides Apiaceae native caraway-leaved lomatium Lomatium caruifolium var. caruifolium Apiaceae native woolly-fruited lomatium Lomatium dasycarpum dasycarpum Apiaceae native large-fruited lomatium Lomatium macrocarpum Apiaceae native common lomatium Lomatium utriculatum Apiaceae native Pacific oenanthe Oenanthe sarmentosa Apiaceae native 1 Stanford Working Plant List 1/15/08 wood sweet cicely Osmorhiza berteroi Apiaceae native mountain sweet cicely Osmorhiza chilensis Apiaceae native Gairdner's yampah (List 4) Perideridia gairdneri gairdneri Apiaceae -

USGS DDS-43, Status of Terrestrial Vertebrates

DAVID M. GRABER National Biological Service Sequoia and Kings Canyon Field Station Three Rivers, California 25 Status of Terrestrial Vertebrates ABSTRACT The terrestrial vertebrate wildlife of the Sierra Nevada is represented INTRODUCTION by about 401 regularly occurring species, including three local extir- There are approximately 401 species of terrestrial vertebrates pations in the 20th century. The mountain range includes about two- that use the Sierra Nevada now or in recent times according thirds of the bird and mammal species and about half the reptiles to the California Wildlife Habitat Relationships System and amphibians in the State of California. This is principally because (CWHR) (California Department of Fish and Game 1994) (ap- of its great extent, and because its foothill woodlands and chaparral, pendix 25.1). Of these, thirteen are essentially restricted to mid-elevation forests, and alpine vegetation reflect, in structure and the Sierra in California (one of these is an alien; i.e. not native function if not species, habitats found elsewhere in the State. About to the Sierra Nevada); 278 (eight aliens) include the Sierra in 17% of the Sierran vertebrate species are considered at risk by state their principal range; and another 110 (six aliens) use the Si- or federal agencies; this figure is only slightly more than half the spe- erra as a minor portion of their range. Included in the 401 are cies at risk for the state as a whole. This relative security is a function 232 species of birds; 112 species of mammals; thirty-two spe- of the smaller proportion of Sierran habitats that have been exten- cies of reptiles; and twenty-five species of amphibians (ap- sively modified.