Understanding Frank Lloyd Wright's Agrarian Vision

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reciprocal Sites Membership Program

2015–2016 Frank Lloyd Wright National Reciprocal Sites Membership Program The Frank Lloyd Wright National Reciprocal Sites Program includes 30 historic sites across the United States. FLWR on your membership card indicates that you enjoy the National Reciprocal sites benefit. Benefits vary from site to site. Please check websites listed in this brochure for detailed information on each site. ALABAMA ARIZONA CALIFORNIA FLORIDA 1 Rosenbaum House 2 Taliesin West 3 Hollyhock House 4 Florida Southern College 601 RIVERVIEW DRIVE 12621 N. FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT BLVD BARNSDALL PARK 750 FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT WAY FLORENCE, AL 35630 SCOTTSDALE, AZ 85261-4430 4800 HOLLYWOOD BLVD LAKELAND, FL 33801 256.718.5050 480.860.2700 LOS ANGELES, CA 90027 863.680.4597 ROSENBAUMHOUSE.COM FRANKLLOYDWRIGHT.ORG 323.644.6269 FLSOUTHERN.EDU/FLW WRIGHTINALABAMA.COM FOR UP-TO-DATE INFORMATION BARNSDALL.ORG FOR UP-TO-DATE INFORMATION FOR UP-TO-DATE INFORMATION TOUR HOURS: 9AM–4PM FOR UP-TO-DATE INFORMATION TOUR HOURS: TOUR HOURS: BOOKSHOP HOURS: 8:30AM–6PM TOUR HOURS: THURS–SUN, 11AM–4PM OPEN ALL YEAR, EXCEPT OPEN ALL YEAR, EXCEPT TOUR TICKETS AVAILABLE AT THE THANKSGIVING, CHRISTMAS AND NEW Experience firsthand Frank Lloyd MAJOR HOLIDAYS. HOLLYHOCK HOUSE VISITOR’S CENTER YEAR’S DAY. 10AM–4PM Wright’s brilliant ability to integrate TUES–SAT, 10AM–4PM IN BARNSDALL PARK. VISITOR CENTER & GIFT SHOP HOURS: SUN, 1PM–4PM indoor and outdoor spaces at Taliesin Hollyhock House is Wright’s first 9:30AM–4:30PM West—Wright’s winter home, school The Rosenbaum House is the only Los Angeles project. Built between and studio from 1937-1959, located Discover the largest collection of Frank Lloyd Wright-designed 1919 and 1923, it represents his on 600 acres of dramatic desert. -

Taliesin West

WELCOME TO TALIESIN WEST PRIVATE EVENTS AT TALIESIN WEST Set in the foothills of the McDowell Mountains, Taliesin West is one of Frank Lloyd Wright’s most personal creations. Wright’s vision and legacy continue to thrive at this unique location. A desert escape just minutes from the resorts of Scottsdale, Taliesin West is unlike any other location in the Valley of the Sun to host your event. Here your guests will have the opportunity to engage with Frank Lloyd Wright’s vision and legacy at the only National Historic site in Scottsdale, and one of two UNESCO World Heritage sites in Arizona. Take a private tour of the property, enjoy a performance on an acoustically perfect stage while sipping a glass of wine, and wow your guests with a dinner overlooking the Valley at sunset. Soak up the history, innovation, and awe that can only be found at Taliesin West. EXPLORE THE VENUES PHOTO BY SUNSHINE & REIGN PHOTOGRAPHY PHOTO BY SUNSHINE & REIGN PHOTOGRAPHY PHOTO BY ANDREW PIELAGE THE CABARET INDOOR Ω SEATS 50 Ω STANDING 60 The Cabaret Theatre is the perfect space for you and your guests to experience the brilliance and delight of a Frank Lloyd Wright design. The unique slope and shape of the room allow for unimpeded views of the small stage below and carry sound perfectly through the space. Perfect for an intimate evening of dining at Wright-designed tables or a performance that offers an PHOTO BY ANDREW PIELAGE exceptional experience found nowhere else. Taliesin West Private Events 2 EXPLORE THE VENUES PHOTO BY TERRY RISHEL GARDEN SQUARES OUTDOOR Ω SEATS 250 Ω STANDING 350 With views of the Music Pavilion, Wright’s Studio, and the McDowell Mountains, the Garden Squares are the perfect venue for groups large or small. -

One Man's Quest to Photograph Every Frank Lloyd Wright Structure Ever Built

One Man's Quest to Photograph Every Frank Lloyd Wright Structure Ever Built architecturaldigest.com /story/frank-lloyd-wright-photographer-andrew-pielage Chris Malloy There are 532 Frank Lloyd Wright structures standing in the world. Phoenix-based photographer Andrew Pielage is on a mission to shoot every one of them. The 39-year-old is the unofficial photographer of the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation. So far, he has shot about 50 Wright structures. His quest to shoot Wright’s oeuvre began in 2011, when he first toured Taliesin West, Wright’s former winter home and studio outside Phoenix. Photography wasn’t allowed on that tour. But later a friend connected Pielage with the folks at Taliesin West, and for them Pielage shot the sprawling stone-and-wood compound. The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation loved his work, and he became its unofficial photographer. Since then, Pielage has shot Wright’s Hollyhock House (Los Angeles), Unity Temple (Illinois), Taliesin (Wisconsin), and Fallingwater (Pennsylvania), where he did a three-week residence. “When you have that much time to shoot a property, you get to know the ins and outs,” he says. What impressed him was how, against the grain of the bright shots one typically sees of the house, Fallingwater, on cloudy days, “turns gray so that the building’s personality changes with the environment.” The spirit of Wright’s organic style, of structures inspired by and seamlessly integrated into the natural world, whether desert or city or forest, has challenged Pielage. How can one properly capture this architectural titan’s work? Pielage has developed tricks. -

Stained Glass Window Designs of Frank Lloyd Wright Pdf, Epub, Ebook

STAINED GLASS WINDOW DESIGNS OF FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Dennis Casey | 32 pages | 21 Mar 1997 | Dover Publications Inc. | 9780486295169 | English | New York, United States Stained Glass Window Designs of Frank Lloyd Wright PDF Book They are similar to the windows of the Dana house, incorporating similar motifs and the same materials. Taliesin is like a brow because it sets on the side of a hill. You might like to try orange muntins in a plain white kitchen, for instance. In , he redrew the plans, changing the stucco exterior to concrete. The house sat on an acre estate and also included a studio and architecture school. About one hundred of Frank Lloyd Wright's buildings have been destroyed for various reasons. Without the casement sash, Wright probably would not have developed the complex and intriguing ornamental patterns found in his windows. Wright gave no specific titles to them. The Larkin Building was modern for its time, with conveniences like air conditioning. Rogers for his daughter and her husband, Frank Wright Thomas. Although Victorian in inspiration, it is a stepping stone to the Prairie window, to which Wright was able to leap directly in in his Studio office and reception room, which he added to his home in that year. Taliesin West is a school for architecture, but it also served as Wright's winter home until his death in The Storer House is another example of Wright using ancient Mayan influences. Striking Minimalism Classic black and white might not seem all that adventurous, but it brings a timeless sense of style to any home window design. -

Organic Grain Production Research and Best Practices

Organic Grain Production Research and Best Practices Joel Gruver – [email protected] What is organic agriculture??? Why didn’t Dr. Hopkins recommend K fertilizer? Franklin Hiram King (1848-1911) FH King , Professor of Soil Physics at UW was dismayed by the rapid degradation of Midwest soils during the 19th century and traveled to Asia looking for answers. “ We desired to learn how it is Farmers of 40 Centuries: possible, after twenty and Permanent Agriculture in perhaps thirty or even forty China, Korea and Japan centuries, for their soils to be was the original title. made to produce sufficiently for the maintenance of such dense populations.. “ Farmers of Forty Centuries, 1911 JR Smith was a pioneer in the field of economic geography, an author of many popular elementary First edition school – college in 1929 level geography text books and a dedicated conservationist and agro-forester. In An Agricultural Testament (1940) Howard laid out his vision for agriculture based on nature as a model with great emphasis on a concept that is central to organic farming--the importance of utilizing organic waste materials to build soil organic matter and maintain soil fertility. An Agricultural Testament by Sir Albert Howard Chapter 1 Introduction THE maintenance of the fertility of the soil is the first condition of any permanent system of agriculture. In the ordinary processes of crop production fertility is steadily lost: its continuous restoration by means of manuring and soil management is therefore imperative. In 1940, Northbourne introduced his concept of the ideal farm as an ORGANIC whole (i.e. having a complex interrelationship of parts/organs, similar to that in living things) in a book titled, Look to the Land. -

A Case Study of Post 3/11/2011 Organic Farmers in Saga, Fukuoka, Kagawa, and Hyogo Prefectures Seth A.Y

Seton Hall University eRepository @ Seton Hall Theses Spring 5-2012 The oM vement for Sustainable Agricultural in Japan: A Case Study of Post 3/11/2011 Organic Farmers in Saga, Fukuoka, Kagawa, and Hyogo Prefectures Seth A.Y. Davis Seton Hall University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.shu.edu/theses Part of the Agricultural and Resource Economics Commons, and the Asian Studies Commons Recommended Citation Davis, Seth A.Y., "The oM vement for Sustainable Agricultural in Japan: A Case Study of Post 3/11/2011 Organic Farmers in Saga, Fukuoka, Kagawa, and Hyogo Prefectures" (2012). Theses. 227. https://scholarship.shu.edu/theses/227 The Movement for Sustainable Agriculture in Japan: A Case Study ofPost 3/11/2011 Organic Farmers in Saga, Fukuoka, Kagawa, and Hyogo Prefectures BY: SETH A.Y. DAVIS B.S., RUTGERS UNIVERSITY NEW BRUNSWICK, NJ 1999 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN THE PROGRAM OF ASIAN STUDIES AT SETON HALL UNIVERSITY SOUTH ORANGE, NEW JERSEY 2012 THE MOVEMENT FOR SUSTAINABLE AGRICULTURE IN JAPAN: A CASE STUDY OF POST 311112011 ORGANIC FARMERS IN SAGA, FUKUOKA, KAGAWA AND HYOGO PREFECTURES THESIS TITLE BY SETH A.Y. DAVIS APPROVED MONTH, DAY, YEAR SHIGER OSUKA, Ed.D MENTOR (FIRST READER) EDWIN PAK-WAH LEUNG, Ph.D EXAMINER (SECOND READER) t;jlO /2-012 MARIA SIBAU, Ph.D EXAMINER (THIRD READER) An1Y ~Mr1i ANNE MULLEN-HOHL, Ph.D HEAD OF DEPARTMENT A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN THE PROGRAM OF ASIAN STUDIES AT SETON HALL UNIVERSITY, SOUTH ORANGE, NEW JERSEY TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS vi ABSTItJ\CT ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- viii CHAPTER I: INTR0 D U CTION ----------------------------------------------------------- 1. -

Looking for Usonia : Preserving Frank Lloyd Wright's Post-1935 Residential Designs As Generators of Cultural Landscapes William Randall Brown Iowa State University

Masthead Logo Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1-1-2006 Looking for Usonia : preserving Frank Lloyd Wright's post-1935 residential designs as generators of cultural landscapes William Randall Brown Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Recommended Citation Brown, William Randall, "Looking for Usonia : preserving Frank Lloyd Wright's post-1935 residential designs as generators of cultural landscapes" (2006). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 18982. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/18982 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Looking for Usonia: Preserving Frank Lloyd Wright's post-1935 residential designs as generators of cultural landscapes by William Randall Brown A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Major: Architectural Studies Program of Study Committee: Arvid Osterberg, Major Professor Daniel Naegele Karen Quance Jeske Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2006 Copyright ©William Randall Brown, 2006. All rights reserved. 11 Graduate C of I ege Iowa State University This i s to certify that the master' s thesis of V~illiam Randall Brown has met the thesis requirements of Iowa State University :atures have been redact` 111 LIST OF TABLES iv ABSTRACT v INTRODUCTION 1 LITERATURE REVIEW 5 CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK The state of Usonia 8 A brief history of Usonia 9 The evolution of Usonian design 13 Preserving Usonia 19 Toward a cultural landscape 21 METHODOLOGY 26 CASE STUDIES: HOUSE MUSEUMS ON PRIVATE LAND No. -

Farmers of Forty Centuries Or Permanent Agriculture in China, Korea and Japan, 1911-2011

Vol.2, No.3, 175-180 (2011) Agricultural Sciences doi:10.4236/as.2011.23024 The making of an agricultural classic: farmers of forty centuries or permanent agriculture in China, Korea and Japan, 1911-2011 John Paull Institute of Social and Cultural Anthropology, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK; Corresponding Author: [email protected] Received 17 May 2011; revised 23 June 2011; accepted 19 July 2011. ABSTRACT ing the first nine decades, while 16 have ap- peared in the past decade. Few agriculture books achieve the status of ‘classic’. F. H. King’s book Farmers of Forty Keywords: Organic Agriculture; Organic Farming; Centuries or Permanent Agriculture in China, Biodynamic Agriculture; Franklin Hiram King; Korea and Japan was privately published in Cyril Hopkins; Jonathan Cape; London. Wisconsin, USA, in 1911. The book had an in- auspicious start, and the longevity and acclaim 1. INTRODUCTION that this book has since achieved must have In his 1940 manifesto of organic farming, Look to the been, then, barely conceivable. The author was Land, Lord Northbourne described Farmers of Forty dead, the book was incomplete, and there was Centuries as a “classic” [1] and as “that great book by no commercial publisher. Yet through a com- Professor King et al. Farmers of Forty Centuries, a book bination of perhaps luck and circumstance the which no student of farming or social science can afford book was ‘resurrected’ in 1927 by a London to ignore” [1]. Eve Balfour in her 1943 book The Living publisher, Jonathan Cape, who then kept it in Soil followed Northbourne’s lead and also described print for more than two decades. -

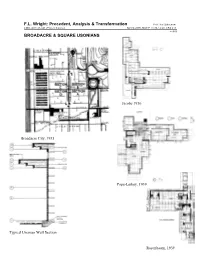

F.L. Wright: Precedent, Analysis & Transformation BROADACRE

F.L. Wright: Precedent, Analysis & Transformation Prof. Kai Gutschow CMU, Arch 48-441 (Project Course) Spring 2005, M/W/F 11:30-12:20, CFA 211 4/15/05 BROADACRE & SQUARE USONIANS Jacobs 1936 Broadacre City, 1935 Pope-Leihey, 1939 Typical Usonian Wall Section Rosenbaum, 1939 F.L. Wright: Precedent, Analysis & Transformation Prof. Kai Gutschow CMU, Arch 48-441 (Project Course) Spring 2005, M/W/F 11:30-12:20, CFA 211 4/15/05 USONIAN ANALYSIS Sergeant, John. FLW’s Usonian Houses McCarter, Robert. FLW. Ch. 9 Jacobs, Herbert. Building with FLW MacKenzie, Archie. “Rewriting the Natural House,” in Morton, Terry. The Pope-Keihey House McCarter, A Primer on Arch’l Principles P. & S. Hanna. FLW’s Hanna House Burns, John. “Usonian Houses,” in Yesterday’s Houses... De Long, David. Auldbrass. Handlin, David. The Modern Home Reisely, Roland Usonia, New York Wright, Gwendolyn. Building the Dream Rosenbaum, Alvin. Usonia. FLW’s Designs... FLW CHRONOLOGY 1932-1959 1932 FLW Autobiography published, 1st ed. (also 1943, 1977) FLW The Disappearing City published (decentralization advocated) May-Oct. "Modern Architecture" exhibit at MoMA, NY (H.R. Hitchcock & P. Johnson, Int’l Style) Malcolm Wiley Hse., Proj. #1, Minneapolis, MN (revised and built 1934) Oct. Taliesin Fellowship formed, 32 apprentices, additions to Taliesin Bldgs. 1933 Jan. Hitler comes to power in Germany, diaspora to America: Gropius (Harvard, 1937), Mies v.d. Rohe (IIT, 1939), Mendelsohn (Berkeley, 1941), A. Aalto (MIT, 1942) Mar. F.D. Roosevelt inaugurated, New Deal (1933-40) “One hundred days.” 25% unemployment. A.A.A., C.C.C. P.W.A., N.R.A., T.V.A., F.D.I.C. -

Frank Lloyd Wright Was Born in Richland Centre, Wisconsin on June 8, 1867

FFrraannkk LLllooyydd WWrriigghhtt report by alexander gruber and rudolf hainzl Biography Frank Lloyd Wright was born in Richland Centre, Wisconsin on June 8, 1867. His parents, William Cary Wright and Anna Lloyd-Jones, originally named him Frank Lincoln Wright, which he later changed after they divorced. When he was twelve years old, Wright's family settled in Madison, Wisconsin where he attended Madison High School. During summers spent on his Uncle James Lloyd Jones' farm in Spring Green, Wisconsin, Wright first began to realize his dream of becoming an architect. In 1885, he left Madison without finishing high school to work for Allan Conover, the Dean of the University of Wisconsin's Engineering department. While at the University, Wright spent two semesters studying civil engineering before moving to Chicago in 1887. In Chicago, he worked for architect Joseph Lyman Silsbee. Wright drafted the construction of his first building, the Lloyd-Jones family chapel, also known as Unity Chapel. One year later, he went to work for the firm of Adler and Sullivan, directly under Louis Sullivan. Wright adapted Sullivan's maxim "Form Follows Function" to his own revised theory of "Form and Function Are One." It was Sullivan's belief that American Architecture should be based on American function, not European traditions, a theory which Wright later developed further. Throughout his life, Wright acknowledged very few influences but credits Sullivan as a primary influence on his career. While working for Sullivan, Wright met and fell in love with Catherine Tobin. The two moved to Oak Park, Illinois and built a home where they eventually raised their five children. -

Charles L. Rosenblum, Ph.D. 3934 California Ave., #2 [email protected] Pittsburgh, PA 15212 412 979 3477

Charles L. Rosenblum, Ph.D. 3934 California Ave., #2 [email protected] Pittsburgh, PA 15212 412 979 3477 Education 2009 Ph.D. in Architectural History, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA Dissertation: The Architecture of Henry Hornbostel Concentrations: American architecture; Modern European, and Renaissance/Baroque 1997 Master of Architectural History, University of Virginia Thesis Topic: "Frank Lloyd Wright's San Francisco Office" 1987 Bachelor of Arts major in art history, Yale University, New Haven, CT Employment (Academic) Fall 2009- Assistant Teaching Professor, School of Architecture, School of Art, Carnegie Mellon University, Spring 2012 Pittsburgh, PA Fall 2000 - Adjunct Assistant Professor, School of Architecture, Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA Spring 2009 Fall 2006 - Adjunct Assistant Professor, School of Art, Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA Spring 2000 Courses at CMU: Critical Histories of the Arts: Spring 2010, 2011, 2012 Modern Visual Culture, Fall 2007-11 Contemporary Visual Culture, Spring 2008 Synergistic Space, Fall 2006 Contemporary Architectural Theory I, Fall 2007, 2008, 2011 Contemporary Architectural Theory II, Spring 2008 History of Sustainable Architecture, Fall 2004, 2010 Spring 2006 Renaissance and Baroque Architecture, Spring 2003-5 “Buzzwords,” Contemporary Architectural Speech, Spring 2002 Architecture of Henry Hornbostel, Fall 2000 – Fall 2003, 2007 Fall 1999 - Adjunct Assistant Professor, Indiana University of Pennsylvania, Indiana, Pennsylvania Spring 2001 Courses at IUP Introduction to Art, Fall 1999 – Spring 2000 Arts of the Twentieth Century, Fall 2000 Modern Art, Spring, Spring 2001 Senior Seminar in Art, Fall 2000 Employment (Professional) 1999 – Architecture Critic, Pittsburgh City Paper. Pittsburgh, PA. Regular column, “Writing on the present Walls,” as well as additional news stories, reviews. -

Frank Lloyd Wright - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Frank Lloyd Wright - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Frank_... Frank Lloyd Wright From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Frank Lloyd Wright (born Frank Lincoln Wright, June 8, 1867 – April 9, Frank Lloyd Wright 1959) was an American architect, interior designer, writer and educator, who designed more than 1000 structures and completed 532 works. Wright believed in designing structures which were in harmony with humanity and its environment, a philosophy he called organic architecture. This philosophy was best exemplified by his design for Fallingwater (1935), which has been called "the best all-time work of American architecture".[1] Wright was a leader of the Prairie School movement of architecture and developed the concept of the Usonian home, his unique vision for urban planning in the United States. His work includes original and innovative examples of many different building types, including offices, churches, schools, Born Frank Lincoln Wright skyscrapers, hotels, and museums. Wright June 8, 1867 also designed many of the interior Richland Center, Wisconsin elements of his buildings, such as the furniture and stained glass. Wright Died April 9, 1959 (aged 91) authored 20 books and many articles and Phoenix, Arizona was a popular lecturer in the United Nationality American States and in Europe. His colorful Alma mater University of Wisconsin- personal life often made headlines, most Madison notably for the 1914 fire and murders at his Taliesin studio. Already well known Buildings Fallingwater during his lifetime, Wright was recognized Solomon R. Guggenheim in 1991 by the American Institute of Museum Architects as "the greatest American Johnson Wax Headquarters [1] architect of all time." Taliesin Taliesin West Robie House Contents Imperial Hotel, Tokyo Darwin D.