How Not to Reconstruct the Iron Age in Shetland: Modern Interpretations of Clickhimin Broch1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![{PDF EPUB} a Guide to Prehistoric and Viking Shetland by Noel Fojut a Guide to Prehistoric and Viking Shetland [Fojut, Noel] on Amazon.Com](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4988/pdf-epub-a-guide-to-prehistoric-and-viking-shetland-by-noel-fojut-a-guide-to-prehistoric-and-viking-shetland-fojut-noel-on-amazon-com-44988.webp)

{PDF EPUB} a Guide to Prehistoric and Viking Shetland by Noel Fojut a Guide to Prehistoric and Viking Shetland [Fojut, Noel] on Amazon.Com

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} A Guide to Prehistoric and Viking Shetland by Noel Fojut A guide to prehistoric and Viking Shetland [Fojut, Noel] on Amazon.com. *FREE* shipping on qualifying offers. A guide to prehistoric and Viking Shetland4/5(1)A Guide to Prehistoric and Viking Shetland: Fojut, Noel ...https://www.amazon.com/Guide-Prehistoric-Shetland...A Guide to Prehistoric and Viking Shetland [Fojut, Noel] on Amazon.com. *FREE* shipping on qualifying offers. A Guide to Prehistoric and Viking ShetlandAuthor: Noel FojutFormat: PaperbackVideos of A Guide to Prehistoric and Viking Shetland By Noel Fojut bing.com/videosWatch video on YouTube1:07Shetland’s Vikings take part in 'Up Helly Aa' fire festival14K viewsFeb 1, 2017YouTubeAFP News AgencyWatch video1:09Shetland holds Europe's largest Viking--themed fire festival195 viewsDailymotionWatch video on YouTube13:02Jarlshof - prehistoric and Norse settlement near Sumburgh, Shetland1.7K viewsNov 16, 2016YouTubeFarStriderWatch video on YouTube0:58Shetland's overrun by fire and Vikings...again! | BBC Newsbeat884 viewsJan 31, 2018YouTubeBBC NewsbeatWatch video on Mail Online0:56Vikings invade the Shetland Isles to celebrate in 2015Jan 28, 2015Mail OnlineJay AkbarSee more videos of A Guide to Prehistoric and Viking Shetland By Noel FojutA Guide to Prehistoric and Viking Shetland - Noel Fojut ...https://books.google.com/books/about/A_guide_to...A Guide to Prehistoric and Viking Shetland: Author: Noel Fojut: Edition: 3, illustrated: Publisher: Shetland Times, 1994: ISBN: 0900662913, 9780900662911: Length: 127 pages : Export Citation:... FOJUT, Noel. A Guide to Prehistoric and Viking Shetland. ... A Guide to Prehistoric and Viking Shetland FOJUT, Noel. 0 ratings by Goodreads. ISBN 10: 0900662913 / ISBN 13: 9780900662911. Published by Shetland Times, 1994, 1994. -

Theses Digitisation: This Is a Digitised

https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ Theses Digitisation: https://www.gla.ac.uk/myglasgow/research/enlighten/theses/digitisation/ This is a digitised version of the original print thesis. Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten: Theses https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] VOLUME 3 ( d a t a ) ter A R t m m w m m d geq&haphy 2 1 SHETLAND BROCKS Thesis presented in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor 6f Philosophy in the Facility of Arts, University of Glasgow, 1979 ProQuest Number: 10984311 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10984311 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. -

Program of the 76Th Annual Meeting

PROGRAM OF THE 76 TH ANNUAL MEETING March 30−April 3, 2011 Sacramento, California THE ANNUAL MEETING of the Society for American Archaeology provides a forum for the dissemination of knowledge and discussion. The views expressed at the sessions are solely those of the speakers and the Society does not endorse, approve, or censor them. Descriptions of events and titles are those of the organizers, not the Society. Program of the 76th Annual Meeting Published by the Society for American Archaeology 900 Second Street NE, Suite 12 Washington DC 20002-3560 USA Tel: +1 202/789-8200 Fax: +1 202/789-0284 Email: [email protected] WWW: http://www.saa.org Copyright © 2011 Society for American Archaeology. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reprinted in any form or by any means without prior permission from the publisher. Program of the 76th Annual Meeting 3 Contents 4................ Awards Presentation & Annual Business Meeting Agenda 5………..….2011 Award Recipients 11.................Maps of the Hyatt Regency Sacramento, Sheraton Grand Sacramento, and the Sacramento Convention Center 17 ................Meeting Organizers, SAA Board of Directors, & SAA Staff 18 ............... General Information . 20. .............. Featured Sessions 22 ............... Summary Schedule 26 ............... A Word about the Sessions 28…………. Student Events 29………..…Sessions At A Glance (NEW!) 37................ Program 169................SAA Awards, Scholarships, & Fellowships 176................ Presidents of SAA . 176................ Annual Meeting Sites 178................ Exhibit Map 179................Exhibitor Directory 190................SAA Committees and Task Forces 194…….…….Index of Participants 4 Program of the 76th Annual Meeting Awards Presentation & Annual Business Meeting APRIL 1, 2011 5 PM Call to Order Call for Approval of Minutes of the 2010 Annual Business Meeting Remarks President Margaret W. -

Cetaceans of Shetland Waters

CETACEANS OF SHETLAND The cetacean fauna (whales, dolphins and porpoises) of the Shetland Islands is one of the richest in the UK. Favoured localities for cetaceans are off headlands and between sounds of islands in inshore areas, or over fishing banks in offshore regions. Since 1980, eighteen species of cetacean have been recorded along the coast or in nearshore waters (within 60 km of the coast). Of these, eight species (29% of the UK cetacean fauna) are either present throughout the year or recorded annually as seasonal visitors. Of recent unusual live sightings, a fin whale was observed off the east coast of Noss on 11th August 1994; a sei whale was seen, along with two minkes whales, off Muckle Skerry, Out Skerries on 27th August 1993; 12-14 sperm whales were seen on 14th July 1998, 14 miles south of Sumburgh Head in the Fair Isle Channel; single belugas were seen on 4th January 1996 in Hoswick Bay and on 18th August 1997 at Lund, Unst; and a striped dolphin came into Tresta Voe on 14th July 1993, eventually stranding, where it was euthanased. CETACEAN SPECIES REGULARLY SIGHTED IN THE REGION Humpback whale Megaptera novaeangliae Since 1992, humpback whales have been seen annually off the Shetland coast, with 1-3 individuals per year. The species was exploited during the early part of the century by commercial whaling and became very rare for over half a century. Sightings generally occur between May-September, particularly in June and July, mainly around the southern tip of Shetland. Minke whale Balaenoptera acutorostrata The minke whale is the most commonly sighted whale in Shetland waters. -

The Significance of the Ancient Standing Stones, Villages, Tombs on Orkney Island

The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism Volume 5 Print Reference: Pages 561-572 Article 43 2003 The Significance of the Ancient Standing Stones, Villages, Tombs on Orkney Island Lawson L. Schroeder Philip L. Schroeder Bryan College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/icc_proceedings DigitalCommons@Cedarville provides a publication platform for fully open access journals, which means that all articles are available on the Internet to all users immediately upon publication. However, the opinions and sentiments expressed by the authors of articles published in our journals do not necessarily indicate the endorsement or reflect the views of DigitalCommons@Cedarville, the Centennial Library, or Cedarville University and its employees. The authors are solely responsible for the content of their work. Please address questions to [email protected]. Browse the contents of this volume of The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism. Recommended Citation Schroeder, Lawson L. and Schroeder, Philip L. (2003) "The Significance of the Ancient Standing Stones, Villages, Tombs on Orkney Island," The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism: Vol. 5 , Article 43. Available at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/icc_proceedings/vol5/iss1/43 THE SIGNIFICANCE OF THE ANCIENT STANDING STONES, VILLAGES AND TOMBS FOUND ON THE ORKNEY ISLANDS LAWSON L. SCHROEDER, D.D.S. PHILIP L. SCHROEDER 5889 MILLSTONE RUN BRYAN COLLEGE STONE MOUNTAIN, GA 30087 P. O. BOX 7484 DAYTON, TN 37321-7000 KEYWORDS: Orkney Islands, ancient stone structures, Skara Brae, Maes Howe, broch, Ring of Brodgar, Standing Stones of Stenness, dispersion, Babel, famine, Ice Age ABSTRACT The Orkney Islands make up an archipelago north of Scotland. -

University of Bradford Ethesis

University of Bradford eThesis This thesis is hosted in Bradford Scholars – The University of Bradford Open Access repository. Visit the repository for full metadata or to contact the repository team © University of Bradford. This work is licenced for reuse under a Creative Commons Licence. THE NEOLITHIC AND LATE IRON AGE POTTERY FROM POOL, SANDAY, ORKNEY An archaeological and technological consideration of coarse pottery manufacture at the Neolithic and Late Iron Age site of Pool, Orkney, incorporating X-Ray Fluorescence, Inductively Coupled Plasma Spectrometric and Petrological Analyses 2 Volumes Volume 1 Ann MACSWEEN submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Archaeological Sciences University of Bradford 1990 ABSTRACT Ann MacSween The Neolithic and Late Iron Age Pottery from Pool, Sanday, Orkney: An archaeological and technological consideration of coarse pottery manufacture at the Iron Age site of Pool, Orkney, incorporating X-Ray Fluorescence, Inductively Coupled Plasma Spectrometric and Petrological Analyses Key Words: Neolithic; Iron Age; Orkney; pottery; X-ray Fluorescence; Inductively Coupled Plasma Spectrometry; Petrological Analysis The Neolithic and late Iron Age pottery from the settlement site of Pool, Sanday, Orkney, was studied on two levels. Firstly, a morphological and tech- nological study was carried out to establish a se- quence for the site. Secondly an assessment was made of the usefulness of X-ray Fluorescence Analysis, In- ductively Coupled Plasma Spectrometry and Petrological analysis to coarse ware studies, using the Pool assem- blage as a case study. Recording of technological and typological attributes allowed three phases of Neolithic pottery to be iden- tified. The earliest phase included sherds of Unstan Ware. -

MODERN PROCESSES and PLEISTOCENE LEGACIES by Louise M. Farquharson, Msc. a Dissertation Submitted In

ARCTIC LANDSCAPE DYNAMICS: MODERN PROCESSES AND PLEISTOCENE LEGACIES By Louise M. Farquharson, MSc. A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Geology University of Alaska Fairbanks December 2017 APPROVED: Daniel Mann, Committee Chair Vladimir Romanovsky, Committee Co-Chair Guido Grosse, Committee Member Benjamin M. Jones, Committee Member David Swanson, Committee Member Paul McCarthy, Chair Department of Geoscience Paul Layer, Dean College of Natural Science and Mathematics Michael Castellini, Dean of the Graduate School Abstract The Arctic Cryosphere (AC) is sensitive to rapid climate changes. The response of glaciers, sea ice, and permafrost-influenced landscapes to warming is complicated by polar amplification of global climate change which is caused by the presence of thresholds in the physics of energy exchange occurring around the freezing point of water. To better understand how the AC has and will respond to warming climate, we need to understand landscape processes that are operating and interacting across a wide range of spatial and temporal scales. This dissertation presents three studies from Arctic Alaska that use a combination of field surveys, sedimentology, geochronology and remote sensing to explore various AC responses to climate change in the distant and recent past. The following questions are addressed in this dissertation: 1) How does the AC respond to large scale fluctuations in climate on Pleistocene glacial-interglacial time scales? 2) How do legacy effects relating to Pleistocene landscape dynamics inform us about the vulnerability of modern land systems to current climate warming? and 3) How are coastal systems influenced by permafrost and buffered from wave energy by seasonal sea ice currently responding to ongoing climate change? Chapter 2 uses sedimentology and geochronology to document the extent and timing of ice-sheet glaciation in the Arctic Basin during the penultimate interglacial period. -

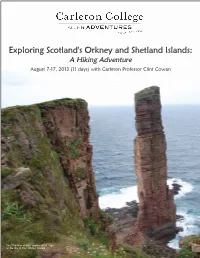

With Carleton Professor Clint Cowan

August 7-17, 2013 (11 days) with Carleton Professor Clint Cowan The "Old Man of Hoy" stands 450 ft. high on the Isle of Hoy, Orkney Islands. Dear Carleton College Alumni and Friends, I invite you to join Carleton College geologist Clint Cowan ’83 on this unique new hiking tour in Scotland’s little-visited Orkney and Shetland Islands! This is the perfect opportunity to explore on foot Scotland’s Northern Isles' amazing wealth of geological and archaeological sites. Their rocks tell the whole story, spanning almost three billion years. On Shet- land you will walk on an ancient ocean floor, explore an extinct volcano, and stroll across shifting sands. In contrast, Orkney is made up largely of sedimentary rocks, one of the best collections of these sediments to be seen anywhere in the world. Both archipelagoes also have an amazing wealth of archaeological sites dating back 5,000 years. This geological and archaeological saga is worth the telling, and nowhere else can the evidence be seen in more glorious a setting. Above & Bottom: The archaeological site of Jarlshof, dat- ing back to 2500 B.C. Below: A view of the Atlantic from This active land tour features daily hikes that are easy to moderate the northern Shetland island of Unst. in difficulty, so to fully enjoy and visit all the sites on this itinerary one should be in good walking condition (and, obviously, enjoy hiking!). Highlights include: • The “Heart of Neolithic Orkney,” inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1999, including the chambered tomb of Maeshowe, estimated to have been constructed around 2700 B.C.; the 4,000 year old Ring of Brodgar, one of Europe’s finest Neolithic monu- ments; Skara Brae settlement; and associated monuments and stone settings. -

Land, Stone, Trees, Identity, Ambition

Edinburgh Research Explorer Land, stone, trees, identity, ambition Citation for published version: Romankiewicz, T 2015, 'Land, stone, trees, identity, ambition: The building blocks of brochs', The Archaeological Journal, vol. 173 , no. 1, pp. 1-29. https://doi.org/10.1080/00665983.2016.1110771 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1080/00665983.2016.1110771 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: The Archaeological Journal General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 01. Oct. 2021 Land, Stone, Trees, Identity, Ambition: the Building Blocks of Brochs Tanja Romankiewicz Brochs are impressive stone roundhouses unique to Iron Age Scotland. This paper introduces a new perspective developed from architectural analysis and drawing on new survey, fieldwork and analogies from anthropology and social history. Study of architectural design and constructional detail exposes fewer competitive elements than previously anticipated. Instead, attempts to emulate, share and communicate identities can be detected. The architectural language of the broch allows complex layers of individual preferences, local and regional traditions, and supra-regional communications to be expressed in a single house design. -

Old School, Sandwick, Shetland, ZE2 9HH

© Richard Gibson Architects Old School, Sandwick, Shetland, ZE2 9HH A unique and rare development opportunity to put a new lease of life into Offers in the region of £55,000 are invited this large historic property, believed to have been built circa 1880, located in the heart of Sandwick. The inside of the property has been stripped to the original stone walls exposing the roof joists, floors and fire places. Main Building:- Large open area and four separate rooms. Richard Gibson Architects (www.rg-architects.com) by complementing Accommodation the existing building and through careful design have produced inspiring, Workshop:- Two rooms and WC. modern plans. The Planning Permission and change of use Building Warrant previously Large enclosed garden ground with granted has now lapsed. Which was to change the main building into two External bespoke, contemporary, semi-detached dwellinghouses. The Workshop gravelled parking and grass areas. also had Planning Permission (now lapsed) for a further one bedroom home. Highly recommended. Please This property is situated next door to the Sandwick Primary & Junior High School and Leisure Centre. It is within easy distance to the local bakery, Viewings contact the Seller on 07885 810 348 grocer, Post Office, play parks, football pitch, community hall and sailing to arrange a viewing. club. Sandwick is approximately half way between Sumburgh Airport to the south and Lerwick some 20 minutes to the north with a good bus service between the two. Early entry is available once Entry conveyancing formalities permit. This property presents an ideal opportunity as a development or renovation project. Further particulars and Home Report from and all offers to:- Anderson & Goodlad, Solicitors 52 Commercial Street, Lerwick, Shetland, ZE1 0BD T: 01595 692297 F: 01595 692247 E: [email protected] W: www.anderson-goodlad.co.uk Main Building The main building is derelict and been completely stripped back to the bare stone walls and roof joists. -

Shetland's Wildlife

Shetland's Wildlife Naturetrek Itinerary Outline Itinerary Day 1 Overnight ferry Aberdeen to Lerwick Day 2/4 Mainland Shetland Day 5 Transfer Mainland to Unst Day 6-7 Unst and Fetlar Day 8/9 Transfer to Lerwick and overnight ferry to Aberdeen Puffin Departs June Focus Birds and mammals Grading B Dates and Prices See website (tour code GBR24) or brochure Highlights Red-necked Phalarope Sea-watching for cetaceans & seabirds on the ferry from Aberdeen to Lerwick Breeding Eider, Storm Petrel, Great & Arctic Skuas Arctic Tern, Puffin, Rock Dove, Twite and Raven Mammals including Grey & Common Seals & Otter Red-throated Diver & Common Scoter on Unst Shetland Mouse-ear Chickweed (Cerastium nigrescens) Ancient settlements of Jarlshof & the Great Broch of Mousa Broch at midnight Mousa Breeding specialties such as Whimbrel on Fetlar Naturetrek Mingledown Barn Wolf’s Lane Chawton Alton Hampshire GU34 3HJ UK T: +44 (0)1962 733051 E: [email protected] W: www.naturetrek.co.uk Shetland's Wildlife Nautetrek Itinerary Introduction The Shetland archipelago consists of about 100 islands which lie to the north-east of Orkney and 280 km from the Faroes. These remote and starkly beautiful islands between the Atlantic and the North Sea are one of Britain’s most exciting wildlife destinations, and in midsummer offer a feast of special breeding birds. Only 15 of the islands are inhabited and the capital, Lerwick, is situated on the largest island, known as ‘Mainland’. This 2-centre holiday (based in Scalloway and on Unst) is carefully timed so that we may have the best views of the many waders which breed in Shetland, in addition to the wealth of nesting seabirds. -

Orkney Historic Properties in Care

Strategic Environmental Assessment of the Orkney Local Development Plan Proposed Plan Appendix B.6: Orkney Scheduled Monuments in the Care of Historic Scotland Name Location Grid reference Earl's Palace Birsay HY248277 Brough of Birsay, settlements, church and related remains Birsay HY239285 St Magnus Church Egilsay HY 466304 Aikerness, Broch of Gurness, broch and settlement Evie HY381268 Eynhallow Church and settlement Eynhallow HY359288 Cuween Hill, chambered cairn Firth HY364127 Rennibister, souterrain Firth HY397126 Wideford Hill, chambered cairn Firth HY409121 Click Mill, 500m ESE of Eastabist Harray HY325288 Dwarfie Stane, rock-cut tomb Hoy HY 244005 Hackness, Battery and Martello Tower Hoy ND 338912 Grain Earth House and Grainbank, two souterrains Kirkwall HY442116 Bishop's Palace Kirkwall HY449108 Earl's Palace Kirkwall HY449107 St Nicholas' Church Orphir HY335044 Earl's Bu, Norse settlement and mill Orphir HY335045 Holm of Papa Westray South, chambered cairn Papa HY 505523 Westray HY484519 Knap of Howar, houses Papa Name Location Grid reference Westray Blackhammer, chambered cairn Rousay HY 414276 Knowe of Yarso, chambered cairn Rousay HY 404279 Midhowe Broch, broch and settlement Rousay HY 371308 HY 372306 Midhowe, chambered cairn and remains nearby Rousay Taversoe Tuick, chambered cairn and nearby HY 426276 remains Rousay Quoyness ,chambered cairn, Els Ness Sanday HY 677378 Skara Brae, settlement, mounds and other remains Sandwick HY229188 Ring of Brodgar, stone circle, henge and nearby remains Stenness HY294132 Maes Howe, chambered