Children's Programming Report;

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Germany As We Saw It

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 045 000 FL 002 074 TITLE Germany as We Saw It. INSTITUTION Stanford Univ., Calif. SPONS AGENCY Office of Education (DFFW), Washington, D.C. PUB DATE 18 Aug 61 NOTE 173p.: Report of 1061 NDEA Institute held at Bad Boll, Germany EDRS PRICE EDRS "Price MF-$0.7c HC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS Area Studies, Churches, Cross Cultural Training, Cultural Background, Cultural Context, Elementary Education, Employment, Family Life, *Foreign Culture, *German, Housing, Inservice Teacher Education, Institutes (Training Programs), International Education, Religion, Secondary Education, *Secondary School Teachers, *Second Language Learning, Study Abroad, *Summer Institutes IDENTIFIERS *Germany, NDEA Language Institutes ABSTRACT Close-up studies of German life in the Stuttgart area are reported by participants of Stanford University's 1051 National Defense Education Act second-level institute for secondary school teachers of German, held at Bad Boll, Germany. Topics covered include: (1) religious life, (2) political life,(3) problems of settlement, (4) occupational problems and the family,(5) aspects of the German educational system, and (6)general cultural life. 17.or related documents see ED 027 785 and ED 027 786. [Not available in hard copy due to marginal legibility of original document.) (WR) U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, EDUCATION & WELFARE OFFICE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRODUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIGINATING IT.POINTS OF VIEW OR OPINIONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENT OFFICIAL OFFICE OF EDUCATION POSITION OR POLICY. -report presented4the'partic.ipants n--the1961 Stanford -NDEA Institule '. eld...at -Bad. Boll,. Germany.. TABLE OF CONTENTS A. Religious Life in Airttemberg p. -

Abandoning the Girl Show Ghetto: Introducing and Incorporating Care Ethics to Girls' Animation

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Adam C. Hughes for the degree of Master of Arts in Applied Ethics presented on July 15, 2013 Title: Abandoning the Girl's Show Ghetto: Introducing and Incorporating Care Ethics to Girls' Animation Abstract approved: Flora L. Leibowitz In regards to animation created and aimed at them, girls are largely underserved and underrepresented. This underrepresentation leads to decreased socio-cultural capital in adulthood and a feeling of sacrificed childhood. Although there is a common consensus in entertainment toward girls as a potentially deficient audience, philosophy and applied ethics open up routes for an alternative explanation of why cartoons directed at young girls might not succeed. These alternative explanations are fueled by an ethical contract wherein producers and content creators respect and understand their audience in return for the privilege of entertaining. ©Copyright by Adam C. Hughes July 15, 2013 All Rights Reserved Abandoning the Girl Show Ghetto: Introducing and Incorporating Care Ethics to Girls' Animation by Adam C. Hughes A THESIS submitted to Oregon State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Presented July 15, 2013 Commencement June 2014 Master of Arts thesis of Adam C. Hughes presented on July 15, 2013 APPROVED: Major Professor, representing Applied Ethics Director of the School of History, Philosophy, and Religion Dean of the Graduate School I understand that my thesis will become part of the permanent collection of Oregon State University libraries. My signature below authorizes the release of my thesis to any reader upon request. Adam C. Hughes, Author ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This author expresses sincere respect for all animators and entertainers who strive to create a better profession for themselves and their audiences. -

Re-Thinking Water and Food Security

RE-THINKING WATER AND FOOD SECURITY Re-thinking Water and Food Security Fourth Botín Foundation Water Workshop Editors Luis Martínez-Cortina Spanish Geological Survey (IGME), Spain Alberto Garrido Research Centre for the Management of Agricultural and Environmental Risks (CEIGRAM), Spain; Technical University of Madrid (UPM), Spain; Marcelino Botin Foundation – Water Observatory (FMB-WO), Spain Elena López-Gunn Marcelino Botin Foundation – Water Observatory (FMB-WO), Spain; London School of Economics (LSE), UK Cover photo: Courtesy of M. Campos and M. Rica Izquierdo. CRC Press/Balkema is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2010 Taylor & Francis Group, London, UK Typeset by MPS Ltd. (A Macmillan Company), Chennai, India Printed and bound in Poland by Poligrafia Janusz Nowak, Poznán All rights reserved. No part of this publication or the information contained herein may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, by photocopying, recording or otherwise, without written prior permission from the publisher. Although all care is taken to ensure integrity and the quality of this publication and the information herein, no responsibility is assumed by the publishers nor the author for any damage to the property or persons as a result of operation or use of this publication and/or the information contained herein. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Marcelino Botín Water Forum (4th : 2009 : Santander, Spain) Re-thinking water and food security : fourth Marcelino Botín Foundation water workshop / editors, Luis Martínez-Cortina, Alberto Garrido, Elena López-Gunn. p. cm. Includes index. ISBN 978-0-415-58790-7 (hard cover : alk. -

A-Z Series Recommendations by Level Summer Is the Perfect Time to Get Lost in a Book Series!

A-Z Series Recommendations by Level Summer is the perfect time to get lost in a book series! A, B, & C Berenstain Bears, Big Bear, Small Bear / Berenstain Biscuit (I Can Read! Level)/ Capucilli Brand New Readers / various authors Clarence the Dragon / Dufresne Dear Zoo and Friends / Campbell Huggles / Crowley I Like Me! / Carlson Oliver the Cat / Renton Tiny the Snow Dog / Meister Tug the Pup and Friends / Wood D Bob Books / Maslen Cat the Cat / Willems Clifford (Level 1) / Bridwell Dr. Seuss Bright and Early Books for Beginning Beginners / various authors I Can Read (My First Shared Reading) / various authors Mrs. Wishy Washy / Crowley Puppy Mudge / Rylant Sam / Lindgren E Little Critter (My First Shared Reading) / Mayer Mittens (My First Shared Reading) / Hartung Pete the Cat (My First I Can Read) / Dean Spot / Hill What People Do Best / Numeroff F Are You Ready to Play Outside? / Willems Biscuit (I Can Read editions) / Capucilli Can I Play Too? / Willems Digger the Dinosaur (My First Shared Reading) / Dolrlich Dumb Bunnies / Pilkey Everything Goes (My First Shared Reading) / Biggs JoJo (I Can Read editions) / O’Connor Mia (My First Shared Reading) / Farley Mr. Men and Little Miss (Reading Ladder) / Hargreaves G Berenstain Bears (Beginning Reading edition) / Berenstain Elephant and Piggie / Willems Eloise (Ready-to-Read) / McNamara Hi! Fly Guy / Arnold Nuts / Litwin Pigeon / Willems Pete the Cat (I Can Read) / Dean H Crabby / Fenske Elephant and Piggie Like Reading / assorted Frog and Friends / Bunting If You Give a … a … / Numeroff Katie Woo / Manushkin Little Critter / Mayer Martha Speaks (readers level 2) / Meddaugh Pictureback(R) / various authors Star Wars: The Clone Wars (DK Readers Pre-level 1) / Richards What is a … (animal) / Schaefer What … Can’t Do / Wood I A …'s Life (nature series) / Himmelman About .. -

Lionsgate® Selected to Distribute Hit Entertainment’S Premiere Family Entertainment Library in North America

LIONSGATE® SELECTED TO DISTRIBUTE HIT ENTERTAINMENT’S PREMIERE FAMILY ENTERTAINMENT LIBRARY IN NORTH AMERICA Agreement Catapults Lionsgate Into Top Three In North American Non-Theatrical Family Home Entertainment Marketplace With Distribution Rights To Thomas & Friends™, Bob the Builder™, Barney™, Angelina Ballerina™ And More SANTA MONICA, CA, VANCOUVER, BC, and LONDON, UK– March 24, 2008 – Reflecting the continued growth of its home entertainment business, Lionsgate (NYSE: LGF), the premier independent filmed entertainment studio, has acquired the home entertainment distribution rights to worldwide family entertainment leader HIT Entertainment’s extensive portfolio of award-winning children’s programming in the US and Canada. The announcement was made today by Lionsgate President and Co-Chief Operating Officer Steve Beeks and HIT Entertainment Chief Financial Officer Jim Weight. Under the terms of the agreement, Lionsgate obtains the exclusive marketing, sales and distribution rights to HIT’s iconic franchises including Thomas & Friends™, Bob the Builder™, Barney™, Angelina Ballerina™and Fireman Sam™ newly acquired brands such as Fifi & the Flowertots™ and Roary the Racing Car™ from Chapman Entertainment, Aardman Animations’ award-winning Wallace & Gromit™ which includes four TV half hour episodes, and Shaun the Sheep™, as well as The Jim Henson Company’s Fraggle Rock™ and additional family titles from the Henson library. Lionsgate is scheduled to begin distributing HIT’s full slate of home entertainment releases in May 2008. Thomas and the Great Discovery, the brand’s first feature length direct to DVD movie since 2005, featuring Pierce Brosnan as the narrator, will be one of the first titles released in September 2008. “The HIT library will be one of the most treasured jewels in our family entertainment crown,” said Lionsgate President and Co-Chief Operating Officer Steve Beeks. -

2 a Quotation of Normality – the Family Myth 3 'C'mon Mum, Monday

Notes 2 A Quotation of Normality – The Family Myth 1 . A less obvious antecedent that The Simpsons benefitted directly and indirectly from was Hanna-Barbera’s Wait ‘til Your Father Gets Home (NBC 1972–1974). This was an attempt to exploit the ratings successes of Norman Lear’s stable of grittier 1970s’ US sitcoms, but as a stepping stone it is entirely noteworthy through its prioritisation of the suburban narrative over the fantastical (i.e., shows like The Flintstones , The Jetsons et al.). 2 . Nelvana was renowned for producing well-regarded production-line chil- dren’s animation throughout the 1980s. It was extended from the 1960s studio Laff-Arts, and formed in 1971 by Michael Hirsh, Patrick Loubert and Clive Smith. Its success was built on a portfolio of highly commercial TV animated work that did not conform to a ‘house-style’ and allowed for more creative practice in television and feature projects (Mazurkewich, 1999, pp. 104–115). 3 . The NBC US version recast Feeble with the voice of The Simpsons regular Hank Azaria, and the emphasis shifted to an American living in England. The show was pulled off the schedules after only three episodes for failing to connect with audiences (Bermam, 1999, para 3). 4 . Aardman’s Lab Animals (2002), planned originally for ITV, sought to make an ironic juxtaposition between the mistreatment of animals as material for scientific experiment and the direct commentary from the animals them- selves, which defines the show. It was quickly assessed as unsuitable for the family slot that it was intended for (Lane, 2003 p. -

HA10 HA18 Bonne Sortie Du HLK Spectacle Kidsport

1976 - 2007 Le Nord LeLVol. 31 e No 43 HearstNordN On ~ Le mercredio 10r janvierd 2007 1,25$ + T.P.S. À érieur Entente Columbia ................HA03 Recrutement ................HA10 Les Élans au Sault ................HA19 Pensée de la semaine Félicitations ! En opposant la Kreison Wabano est notre pre- haine on ne mier bébé de l’année! Kreison fait que la est né par césarienne le 3 janvier 2007 à 21 h 30 à l’Hôpital répandre, en Sensenbrenner de Kapuskasing. surface Il pesait 7 livres et 2 onces à la naissance. Il est le fils de Tim comme en Wabano et Tina Bluff de Constance Lake. Photo profondeur. disponible au journal Le Nord/CP Ghandi Spectacle Kidsport Bonne sortie du HLK HA10 HA18 Mercredi Jeudi Vendredi Samedi Dimanche Lundi Ensoleillé avec Généralement passages nuageux Faible neige Ciel variable Plutôt nuageux Ciel variable Max 2 Min -12 Max -11 Min -19 ensoleillé Max 10 Max -20 Min -20 Max -13 PdP 80% PdP 20% Max -17 Min -23 PdP 10% PdP 0% PdP 60% PdP 20% Nouveau conseil municipal Mattice nomme ses représentants au sein des comités MATTICE (FB) – Le conseil d’administration de l’Association le comité local des citoyens de la représentant municipal sur le la région de Hearst. municipal de Mattice-Val Côté a de recyclage de Cochrane- Forêt de Kapuskasing. Il a aussi Comité de financement du La trésorière Manon Leclerc a nommé ses représentants sur Temiscamingue. M. Tanguay a été désigné représentant du con- Collège Boréal, campus de été désignée comme représen- divers comités ou organismes aussi été désigné maire-adjoint seil au sein du Conseil de Hearst. -

Emotional and Linguistic Analysis of Dialogue from Animated Comedies: Homer, Hank, Peter and Kenny Speak

Emotional and Linguistic Analysis of Dialogue from Animated Comedies: Homer, Hank, Peter and Kenny Speak. by Rose Ann Ko2inski Thesis presented as a partial requirement in the Master of Arts (M.A.) in Human Development School of Graduate Studies Laurentian University Sudbury, Ontario © Rose Ann Kozinski, 2009 Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OttawaONK1A0N4 OttawaONK1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-57666-3 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-57666-3 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

C5348 : Color Pixter® the Fairly Odd Parents Software

C5348a-0920 8/23/04 2:04 PM Page 1 Owner’s Manual Model Number: C5348 C5348a-0920 8/23/04 2:04 PM Page 2 2 C5348a-0920 8/23/04 2:04 PM Page 3 Let’s Go! Before inserting a software cartridge, turn power off! Insert the software cartridge into the software port.Turn power back on. Software Cartridge Software Port • Some of the tools on the tool menu are not available for use in some games or activities. If a tool is not available for use, you will hear a tone. • Please keep this manual for future reference, as it contains important information. IMPORTANT! If the tip of the stylus and the image on screen do not align, it’s time to calibrate them! Please refer to page 39, Calibrating the Stylus. 3 C5348a-0920 8/23/04 2:04 PM Page 4 The Fairly OddParents™ Create & Play! Choose an activity or game from the Home Screen: Magic Art Studio, Cast a Spell, Sewer Search, Catch a Falling Star and Yucky Food Transformer. Touch the activity or game on the screen with the stylus. Magic Art Studio Cast a Spell Sewer Search Catch a Falling Star Yucky Food Transformer 4 C5348a-0920 8/23/04 2:04 PM Page 5 Magic Art Studio Object: Create a FairlyOdd™ Masterpiece! • First, you need to choose a starter background. • Touch the arrows on the bottom of the screen with the stylus to scroll through different backgrounds. • When you find one that you like, touch your choice on the screen with the stylus. -

Friday Prime Time, April 17 4 P.M

April 17 - 23, 2009 SPANISH FORK CABLE GUIDE 9 Friday Prime Time, April 17 4 P.M. 4:30 5 P.M. 5:30 6 P.M. 6:30 7 P.M. 7:30 8 P.M. 8:30 9 P.M. 9:30 10 P.M. 10:30 11 P.M. 11:30 BASIC CABLE Oprah Winfrey Å 4 News (N) Å CBS Evening News (N) Å Entertainment Ghost Whisperer “Save Our Flashpoint “First in Line” ’ NUMB3RS “Jack of All Trades” News (N) Å (10:35) Late Show With David Late Late Show KUTV 2 News-Couric Tonight Souls” ’ Å 4 Å 4 ’ Å 4 Letterman (N) ’ 4 KJZZ 3The People’s Court (N) 4 The Insider 4 Frasier ’ 4 Friends ’ 4 Friends 5 Fortune Jeopardy! 3 Dr. Phil ’ Å 4 News (N) Å Scrubs ’ 5 Scrubs ’ 5 Entertain The Insider 4 The Ellen DeGeneres Show (N) News (N) World News- News (N) Two and a Half Wife Swap “Burroughs/Padovan- Supernanny “DeMello Family” 20/20 ’ Å 4 News (N) (10:35) Night- Access Holly- (11:36) Extra KTVX 4’ Å 3 Gibson Men 5 Hickman” (N) ’ 4 (N) ’ Å line (N) 3 wood (N) 4 (N) Å 4 News (N) Å News (N) Å News (N) Å NBC Nightly News (N) Å News (N) Å Howie Do It Howie Do It Dateline NBC A police of cer looks into the disappearance of a News (N) Å (10:35) The Tonight Show With Late Night- KSL 5 News (N) 3 (N) ’ Å (N) ’ Å Michigan woman. (N) ’ Å Jay Leno ’ Å 5 Jimmy Fallon TBS 6Raymond Friends ’ 5 Seinfeld ’ 4 Seinfeld ’ 4 Family Guy 5 Family Guy 5 ‘Happy Gilmore’ (PG-13, ’96) ›› Adam Sandler. -

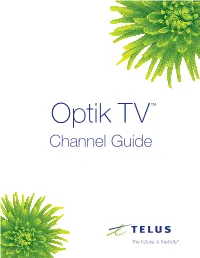

Channel Guide Essentials

TM Optik TV Channel Guide Essentials Fort Grande Medicine Vancouver / Kelowna / Prince Dawson Victoria / Campbell Essential Channels Call Sign Edmonton Lloydminster Red Deer Calgary Lethbridge Kamloops Quesnel Cranbrook McMurray Prairie Hat Whistler Vernon George Creek Nanaimo River ABC Seattle KOMODT 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 AMI-audio* AMIPAUDIO 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 AMI-télé* AMITL 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 AMI-tv* AMIW 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 APTN (West)* ATPNP 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 — APTN HD* APTNHD 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 — BC Legislative TV* BCLEG — — — — — — — — 843 843 843 843 843 843 843 843 843 CBC Calgary* CBRTDT 100 100 100 CBC Edmonton* CBXTDT 100 100 — 100 100 CBC Lloydminster* CKSADT — — 100 — — — — — — — — — — — — — — CBC News Network CBNEWHD 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 CBC Vancouver* CBUTDT 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 CBS Seattle KIRODT 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 CFJC* CFJCDT — — — — — — — — — 115 106 — — — — — — CHAT* CHATDT — — — — — — — 122 — — — — — — — — — CHEK* CHEKDT — — — — — — — — 121 121 121 121 121 121 121 121 121 City Calgary* CKALDT 106 106 106 — City Edmonton* CKEMDT 106 106 106 106 106 — City Vancouver* CKVUDT 106 106 — 106 106 106 -

CHILDRENS Dvds – As of JULY 2014

CHILDRENS DVDs – as of JULY 2014 CHILDREN'S TITLES (including Parent Collection) NRA Abraham Lincoln PG Ace Ventura Jr. pet detective (SDH) NRA Action words, volume 1 NRA Action words, volume 2 NRA Action words, volume 3 NRA Activity TV: Magic, vol. 1 TV-PG Adventure time: The complete first season (2v) (SDH) TV-PG Adventure time: Fionna and Cake (SDH) G Adventures in Zambezia (SDH) NRA Adventures of Bailey: Christmas hero (SDH) NRA Adventures of Bailey: The lost puppy NRA Adventures of Bailey: A night in Cowtown (SDH) G The adventures of Brer Rabbit (SDH) NRA The adventures of Carlos Caterpillar: Litterbug TV-Y The adventures of Chuck & friends: Bumpers up! TV-Y The adventures of Chuck & friends: Friends to the finish TV-Y The adventures of Chuck & friends: Trucks versus wild TV-Y The adventures of Chuck & friends: When trucks fly G The adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad (CC) G The adventures of Milo and Otis (CC) G Adventures of Pinocchio (CC) PG The adventures of Renny the fox (CC) NRA The adventures of Scooter the penguin (SDH) PG The adventures of Sharkboy and Lavagirl in 3-D (SDH) NRA The adventures of Teddy P. Brains: Journey into the rain forest NRA Adventures of the Gummi Bears (3v) (SDH) PG The adventures of TinTin (CC) NRA Adventures with Wink & Blink: A day in the life of a firefighter (CC) NRA Adventures with Wink & Blink: A day in the life of a zoo (CC) G African cats (SDH) PG Agent Cody Banks 2: destination London (CC) PG Alabama moon G Aladdin (2v) (CC) G Aladdin: the Return of Jafar (CC) PG Alex Rider: Operation stormbreaker