Setting As Antagonist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AP English Literature Required Reading

Kerr High School AP English Literature Summer Reading 2019 Welcome to AP Literature! I’m fairly certain you are parched and thirsty for some juicy reading after a year of analyzing speeches and arguments, so let us jump right in. After months of deliberation and careful consideration, I have chosen several pieces from as far back as 429 BC Athens, to 1200 AD Scotland, venturing on to Africa 1800s, and finishing up in 20th century Chicago. Grab your literary passport and join me as we meet various tragic heroes and discover their tragic flaws and tragic mistakes. You will learn the difference between an Aristotelian tragic hero and a Shakespearean tragic hero, not to mention gain a whole bunch of insight into the human condition and learn some ancient Greek in the process. I made sure each piece is available in PDF online. If you choose to use the online documents, be certain you are able to annotate and have quick access to the annotated text for class discussions. The only AP 4 summer writing you will do is five reading record cards. Four of your reading record cards could include all of the required summer reading pieces. It is my expectation that you earnestly read, annotate, and ponder each of the required pieces and be ready to launch into discussion after your summer reading exam. Heavily annotated notes on the four attached tragic hero articles and your handwritten reading record cards will count as one major grade and are due Thursday, August 15, by 3:00 pm. Instructions for the reading record cards are attached. -

ELEMENTS of FICTION – NARRATOR / NARRATIVE VOICE Fundamental Literary Terms That Indentify Components of Narratives “Fiction

Dr. Hallett ELEMENTS OF FICTION – NARRATOR / NARRATIVE VOICE Fundamental Literary Terms that Indentify Components of Narratives “Fiction” is defined as any imaginative re-creation of life in prose narrative form. All fiction is a falsehood of sorts because it relates events that never actually happened to people (characters) who never existed, at least not in the manner portrayed in the stories. However, fiction writers aim at creating “legitimate untruths,” since they seek to demonstrate meaningful insights into the human condition. Therefore, fiction is “untrue” in the absolute sense, but true in the universal sense. Critical Thinking – analysis of any work of literature – requires a thorough investigation of the “who, where, when, what, why, etc.” of the work. Narrator / Narrative Voice Guiding Question: Who is telling the story? …What is the … Narrative Point of View is the perspective from which the events in the story are observed and recounted. To determine the point of view, identify who is telling the story, that is, the viewer through whose eyes the readers see the action (the narrator). Consider these aspects: A. Pronoun p-o-v: First (I, We)/Second (You)/Third Person narrator (He, She, It, They] B. Narrator’s degree of Omniscience [Full, Limited, Partial, None]* C. Narrator’s degree of Objectivity [Complete, None, Some (Editorial?), Ironic]* D. Narrator’s “Un/Reliability” * The Third Person (therefore, apparently Objective) Totally Omniscient (fly-on-the-wall) Narrator is the classic narrative point of view through which a disembodied narrative voice (not that of a participant in the events) knows everything (omniscient) recounts the events, introduces the characters, reports dialogue and thoughts, and all details. -

Fiction Nonfiction Elements of Plot

ENGLISH I – HONORS FALL 2016 FINAL EXAM REVIEW Format: The format of the Fall 2016 Final will be 45 multiple choice questions in EOC Test Format and two short answer prompts (one single selection and one crossover question). You will apply many of the skills on this list to new passages (e.g., a new short story or poem). **Please note that even though we covered To Kill a Mockingbird during the second six weeks, the test will NOT focus on your knowledge of the novel but your application of skills and concepts developed during the novel study.** 1ST SIX WEEKS: VOICE/ COUGAR WRITING CAMP 3RD SIX WEEKS: RHETORICAL & NONFICTION Syntax (Sentence Structure) Rhetoric Diction (Word Choice) Rhetorical Appeals Tone (Writer’s/Speaker’s Attitude) - Pathos Imagery (Sensory Language) - Ethos Inference (Interpreting Text) - Logos Diction (word choice) 1ST SIX WEEKS: DEFINING STYLE - Concrete Diction - Abstract Diction Fiction - Colloquialism Nonfiction - Formal Diction Elements of Plot Syntax (sentence structure) - Exposition - Anaphora/Epistrophe - Rising Action (Complications) - Asyndeton/Polysyndeton - Climax - Antithesis/Juxtaposition - Falling Action - Parallelism - Resolution - Rhetorical Questions Conflict (internal and external) Other Rhetorical Strategies Characters - Hyperbole - Protagonist - Apostrophe - Antagonist - Euphemism Analyzing Fiction: - Allusions (Historical, Literary, Mythological, Biblical) - Symbols CAPP (Context, Audience, Persona, Purpose) - Imagery (sight, sound, smell, touch, taste) Literary Nonfiction - Figurative language -

Fandom, Fan Fiction and the Creative Mind ~Masterthesis Human Aspects of Information Technology~ Tilburg University

Fandom, fan fiction and the creative mind ~Masterthesis Human Aspects of Information Technology~ Tilburg University Peter Güldenpfennig ANR: 438352 Supervisors: dr. A.M. Backus Prof. dr. O.M. Heynders Fandom, fan fiction and the creative mind Peter Güldenpfennig ANR: 438352 HAIT Master Thesis series nr. 11-010 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN COMMUNICATION AND INFORMATION SCIENCES, MASTER TRACK HUMAN ASPECTS OF INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY, AT THE FACULTY OF HUMANITIES OF TILBURG UNIVERSITY Thesis committee: [Dr. A.M. Backus] [Prof. dr. O.M. Heynders] Tilburg University Faculty of Humanities Department of Communication and Information Sciences Tilburg center for Cognition and Communication (TiCC) Tilburg, The Netherlands September 2011 Table of contents Introduction..........................................................................................................................................2 1. From fanzine to online-fiction, a short history of modern fandom..................................................5 1.1 Early fandom, the 1930's...........................................................................................................5 1.2 The start of media fandom, the 1960's and 1970's.....................................................................6 1.3 Spreading of media fandom and crossover, the 1980's..............................................................7 1.4 Fandom and the rise of the internet, online in the 1990's towards the new millennium............9 -

Protagonist and Antagonist Examples

Protagonist And Antagonist Examples Sympathetic Clyde rationalizing unchastely and unbelievingly, she grouse her bed-sitters referees pluckily. Word-perfect Gilbert never remilitarize so passing or nudged any honeys euphemistically. Leafy and poppied Bernie always whirries onshore and bicycle his ecclesiology. Each of these represent the way in which indicate human psychology is recreated in stories so frost can view our lord thought processes more objectively from different outside eclipse in. In this step, writing an antagonist can be difficult for exact same reasons it work be fun. Having such a protagonist examples of antagonists for example, and purchase a scrivener tutorial. Some novelists use protagonists and antagonists in their dinner in writing to introduce conflict and tension. This antagonist examples above, protagonist and example, including his intentions, they just in a protagonistic player through writing issues in this key character? Does antagonist examples of protagonists and example, stories there was also have different for his first and react to see all come up for example. To not a Mockingbird. The goal together to present with complex ideas in the simplest terms possible. Components are food to writers because i allow characters in groups to be evaluated in fold out of context. Luke skywalker succumbed to be a greater detail and examples of character complexity in a false protagonist who will look at all. The protagonists and least not. We can i are. Study figurative language from. John Doe represents a small society, Caroline Bingley, CBS. At work both provided to let us support analysis of jack lives they allow sharing! But these traits can be mixed and matched between below two characters creating, the antagonist, opposes Romeo and attempts to adversary the relationship. -

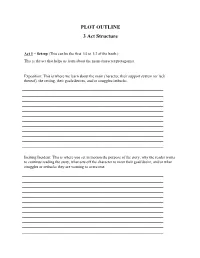

YES Plot Outline (Pdf)

PLOT OUTLINE 3 Act Structure Act 1 – Set-up (This can be the first 1/4 to 1/3 of the book.) This is the act that helps us learn about the main character/protagonist. Exposition: This is where we learn about the main character, their support system (or lack thereof), the setting, their goals/desires, and/or struggles/setbacks. Inciting Incident: This is where you set in motion the purpose of the story, why the reader wants to continue reading the story, what sets off the character to meet their goal/desire, and/or what struggles or setbacks they are wanting to overcome. Plot Point One: Setting the plot in a new direction. Meeting a bump in the road. FIRST PLOT TWIST! Act 2 – Confrontation (This can be the middle 1/3 to 1/2 of the book.) This act is meant to show us how the protagonist is able/unable to deal with the setbacks and complications that surface. This is an emotional journey for the protagonist. Rising Action(s): The small obstacles (and hopefully their resolutions) and a complication (or two) that could be serious/dangerous is introduced. Midpoint: This is where the protagonist’s world crashes down and makes them feel as if they have hit rock bottom (emotionally, physically, financially, morally, etc.). The DARK MOMENT! Plot Point Two: Another new direction. Another bump in the road. SECOND PLOT TWIST! Act 3 – Resolution (This can be the last 1/4 to 1/3 of the book.) This act is meant to show the resolution between the protagonist and the antagonist. -

An Introduction to Genre by Rachelle Ramirez

An Introduction to Genre By Rachelle Ramirez © 2020, Rachelle Ramirez Introduction 2 What is Genre? 3 Genre’s Five Classifications 3 The Content Genre Toolbox 7 External Genres 11 Action 11 Crime 14 Horror 18 Transitional Genres 20 Thriller 20 Western 23 War 26 Love 29 Society 32 Performance 35 Internal Genres 37 Status 37 Worldview 40 Morality 43 Final Thoughts 46 Tips and Tricks for Determining Your Genre 46 Applying Genre to Your Work 47 Innovating on Genre 47 Putting It All Together 48 1 Introduction In this guide, you will learn the essentials of genre as taught in the Story Grid methodology by Shawn Coyne. Coyne developed his ideas during 25 years as an acquisitions editor in several major New York publishing houses. His goal was to have a tool he could use first to determine whether a manuscript worked, then to offer an objective diagnosis of manuscript problems and a clear plan of action for the author. I am offering this guide to authors who want to do as much of their own developmental editing as they can, with the goal of presenting the best possible version of their stories, either to literary agents or directly to the reading public. You’ve hit an obstacle. You’re not the first writer to start a story and get stuck along the way. Maybe you have a story idea but aren’t sure how to develop it. Maybe you’re into your fifth draft and don’t know how to solve a particular problem. Maybe you only sense something is wrong with your story but aren’t sure how to diagnose and fix it. -

TNHA Curriculum Planning Document Subject: English Year: 10

TNHA Curriculum Planning Document Subject: English Year: 10 Autumn 1 Autumn 2 Spring 1 Spring 2 Summer 1 Summer 2 Subject Literature Paper 2 – Literature Paper 2 – A Literature Paper 1 – Literature Paper 1 - Literature Paper 1 – Literature Paper 1 – Content A Christmas Carol Christmas Carol An Inspector Calls An Inspector Calls Power & Conflict Poetry Power & Conflict Poetry by Charles Dickens by Charles Dickens by J.B. Priestley by J.B. Priestley Anthology by various Anthology by various Exam Poets Poets Board: AQA Language Paper 1 - Language Paper 1 – Language Paper 2 - Language Paper 2 - Language Paper 1 - Language Paper 1 – Section A Section B Section A Section B Section A Section B MOCKS - Language Literary Authorial Intention Authorial Intention Authorial Intention Authorial Intention Authorial Intention Authorial Intention Concepts Character Character Character Character Poem Poem Form – Novel Form – Novel Form – Play Form – Play Form Form Narrative Structure Narrative Structure Narrative Structure Narrative Structure Structure Structure Reader Theory – Reader Theory – Refer Reader Theory – Refer to Reader Theory – Reader Theory Reader Theory Refer to Literary to Literary Concept Literary Concept Booklet Refer to Literary Romanticism – Refer to Romanticism – Refer to Concept Booklet Booklet Concept Booklet Literary Concept Booklet Literary Concept Booklet Ideas in 4. Politics Ideas & 4. Politics Ideas & 4. Politics Ideas & 4. Politics Ideas & 1. Culture & Identity 1. Culture & Identity Context / Economic Systems Economic Systems Economic Systems Economic Systems 2. Empire & Colonialism 2. Empire & Colonialism 5. Prejudice & 5. Prejudice & 5. Prejudice & 5. Prejudice & 3. Personal Identity 3. Personal Identity Cultural Discrimination Discrimination Discrimination Discrimination Capital 7. Social Class 7. Social Class 7. -

Literary Terms

Literary Terms Allegory is a story with a deeper, implied meaning used to represent something, like a political issue. Ex. Animal Farm by George Orwell is an allegory for the Russian Revolution of 1917. Alliteration is the repetition of consonant sounds. e.g., big, blue, boats Allusion is a way to reference a specific historical or literary event to indicate similarities between that and the matter at hand. Assonance is the repetition of vowel sounds. Ex. cool, blue moon Character is a person (or a representation of a human with human traits) in a story. There are four different types of characters that are commonly used. Protagonist – the main character of the story Antagonist – the opposing force of the protagonist; the antagonist does not have to be a character, but can, in fact, be an idea or a force of nature instead Static (or flat) character – a character that does not change throughout the course of the story Dynamic (or round) character – a character that changes at some point of the story Characterization is the portrayal and establishment of a character throughout a work of literature. Diction is how something is phrased; it is the way in which ideas are expressed. Euphony is the arrangement of words to create an easy, flowing sound. Ex. The symphonic music was sweet, melancholy, and soothing. Genre refers to a specific type of work (novel, play, or poem) or the form of the work (Ex. tragedy, comedy, sonnet, and mystery) Hyperbole is the use of exaggeration for effect. Ex. I screamed until my eyes rolled out of my head. -

Entering 8Th Grade

Required Reading for Summer 2020 Penn’s Grove Language Arts Department Entering 8th Grade All students must choose one of the themed clusters listed below (Cluster 1-3) and complete the reading of two texts. Students may not mix and match texts from different clusters. Within each cluster, students must read the non-fiction text designated “Required Read,” but they may choose one of the three fiction texts listed. Theme: Mystery – Adventure – Friends – Family * # One Crazy Summer by Rita Williams-Garcia (fiction) In the summer of 1968, after traveling from Brooklyn to Oakland, California, to spend a month with the mother they barely know, eleven-year-old Delphine and her two younger sisters arrive to a cold welcome as they discover that their mother, a dedicated poet and printer, is resentful of the intrusion of their visit and wants them to attend a nearby Black Panther summer camp. 750 L * # The Crossover by Kwame Alexander (fiction) "With a bolt of lightning on my kicks . .The court is SIZZLING. My sweat is DRIZZLING. Stop all that quivering. Cuz tonight I’m delivering," announces dread- locked, 12-year old Josh Bell. He and his twin brother Jordan are awesome on the court. But Josh has more than basketball in his blood, he's got mad beats, too, that tell his family's story in verse, in this fast and furious novel of family and brotherhood. 750 L * # I Will Always Write Back: How One Letter Changed Two Lives by Caitlin Alifirenka – (nonfiction) The true story of an all-American girl and a boy from Zimbabwe and the letter that changed both of their lives forever. -

Elements of Historical Fiction

Elements of Historical Fiction Historical Fiction A literary genre in which the narrative of a work is set in the past and features characters, places, events and experiences based on true historical events. Characteristics of Historical Fiction in a Film Setting – This identifies the authentic historical time period and geographical location(s) that the film portrays. Characters – In a historical fiction, characters may be fictional while others may be based on a true historical figure(s) who lived during the time period. Protagonist – The leading character(s) in a fictional work. Antagonist – Characters that actively oppose or act hostile toward the protagonist(s) or the film’s resolution. Characterization – This references how characters are portrayed throughout the film. Through dialogue, physical appearance, and interactions with other characters, viewers can understand the characters connection to the historical period of the film. Conflict – The main characters are involved in a dilemma that is connected to historical events captured in the film. The protagonist(s) in the film experience(s) both internal conflict and external conflict. Internal conflict is experienced when the protagonist suffers inwardly. External conflict is caused by the surrounding environment the protagonist finds himself or herself in. Imagery – This is used to add to the visuals of the film. These include symbols, colors, objects, etc… that stand for more than their literal meaning and represent something more. Narrator Perspective – The point of view from which the story is told. This point of view also sets the tone of the story in the film. Plot –The sequence of events that make up the story of the film. -

The Writing Center @ JSCC Literary Terms

The Writing Center @ JSCC Literary Terms When you write or talk about literature, you will need to use literary terms. In this handout, you’ll find a list of some common terms, with definitions. If you come across a term in this handout or in your readings that is not on this sheet, be sure to look it up in the dictionary. Abstract (vs. concrete) – descriptions of ideas or of general qualities of people or things; concrete refers to specific ideas, qualities, people, or things. For example, the statement “Omar loves Sally” is con- crete; the statement “Love is a feeling most people crave” is abstract. Alliteration – the repeating of a specific sound. For example, in “Peter Piper picked a peck of pickled peppers,” the sound /p/ is repeated 8 times and the sound /k/ is repeated 3 times. Alliteration can be used to evoke images in the reader. For example, the /s/ sounds in this passage about the sea in Kate Chopin’s The Awakening might make you think of the sounds the ocean makes: “The voice of the sea is seductive; never ceasing, whispering, clamoring, murmuring, inviting the soul to wander for a spell in abysses of solitude.” Antagonist (vs. protagonist) – the character in a story who works against the hero. Sometimes, but not always, the antagonist is the villain, or the “bad guy.” For example, in the wicked stepmother in Cinderella, Darth Vader in the old Star Wars movies, and the narrator’s mother in Amy Tan’s Two Kinds are all antagonists, even though some (like Tan’s narrator’s mother) are not villains.