Max Ophuls Walter C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LA RONDE EXPLORES PSYCHOLOGICAL DANCE of RELATIONSHIPS New Professor Brings Edgy Movement to Freudian-Inspired Play

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: January 30, 2009 PASSION, POWER & SEDUCTION – LA RONDE EXPLORES PSYCHOLOGICAL DANCE OF RELATIONSHIPS New professor brings edgy movement to Freudian-inspired play. 2008/2009 Season What better time to dissect the psychology of relationships and human sexuality than just after Valentine’s Day? 3 LA RONDE Where better than at the University of Victoria Phoenix Theatre's production of La Ronde, February 19 to 28, 2009. February 19 – 28, 2009 By Arthur Schnitzler Steeped in the struggles of psychology, sex, relationships and social classes, Arthur Schnitzler's play La Ronde, Direction: Conrad Alexandrowicz th Set & Lighting Design: Paphavee Limkul (MFA) written in 1897, explores ten couples in Viennese society in the late 19 century. Structured like a round, in music or Costume Design: Cat Haywood (MFA) dance, La Ronde features a cast of five men and five women and follows their intricately woven encounters through Stage Manager: Lydia Comer witty, innuendo-filled dialogue. From a soldier and a prostitute, to an actress and a count, their intimate A psychological dance of passion, power and relationships transcend social and economic status to comment on the sexual mores of the day. Schnitzler himself seduction through Viennese society in the 1890s. was no stranger to such curiosities. A close friend of Sigmund Freud, Schnitzler was considered Freud's creative Advisory: Mature subject matter, sexual equivalent. He shared Freud’s fascination with sex: historians have noted that he began frequenting prostitutes at content. age sixteen and recording meticulously in his diary an analysis of every orgasm he achieved! Recently appointed professor of acting and movement, director Conrad Alexandrowicz gives La Ronde a contemporary twist while maintaining the late 19th century period of the play. -

Philosophy Physics Media and Film Studies

MA*E299*63 This Exploration Term project will examine the intimate relationship Number Theory between independent cinema and film festivals, with a focus on the Doug Riley Sundance Film Festival in Park City, Utah. Film festivals have been central Prerequisites: MA 231 (for mathematical maturity) to international and independent cinema since the 1930s. Sundance Open To: All Students is the largest independent film festival in the United States and has Grading System: Letter launched the careers of filmmakers like Paul Thomas Anderson, Kevin Max. Enrollment: 16 Smith, and Quentin Tarantino. During this project, students will study Meeting Times: M W Th 10:00 am–12:00 pm, 1:30 pm–3:30 pm the history of film festivals and the ways in which they have influenced the landscape of contemporary cinema. The class will then travel to the Number Theory is the study of relationships and patterns among the Sundance Film Festival for the last two weeks of the term to attend film integers and is one of the oldest sub-disciplines of mathematics, tracing screenings, panels, workshops and to interact with film producers and its roots back to Euclid’s Elements. Surprisingly, some of the ideas distributers. explored then have repercussions today with algorithms that allow Estimated Student Fees: $3200 secure commerce on the internet. In this project we will explore some number theoretic concepts, mostly based on modular arithmetic, and PHILOSOPHY build to the RSA public-key encryption algorithm and the quadratic sieve factoring algorithm. Mornings will be spent in lecture introducing ideas. PL*E299*66 Afternoons will be spent on group work and student presentations, with Philosophy and Film some computational work as well. -

Our Love Affair with Movies

OUR LOVE AFFAIR WITH MOVIES A movie producer and Class of ’68 alumnus recalls the cinematic passions of his senior year—and offers some advice on rekindling the romance for today’s audiences. By Robert Cort crush on movies began on a Around the World was a grand spectacle Louis Jourdan as Gaston realizing how damp November night in 1956. that ultimately claimed the Academy much he loved Gigi and pursuing her Dressed in my first suit—itchy Award for Best Picture. Beyond its exotic through Paris singing, “Gigi, what mir- MY and gray—I sat in the backseat locales, it was my first experience of char- acle has made you the way you are?” of our Oldsmobile as my parents crossed acters attempting the impossible. When Before that scene, what I’d observed the Brooklyn Bridge into Manhattan. At David Niven as Phineas Fogg realized about men and women in love was my Mama Leone’s I tasted Parmesan cheese that crossing the International Date Line parents’ marriage, and that didn’t seem for the first time. Then we walked a few had returned him to London on Day 80, something to pine for. blocks to the only theater in the world the communal exuberance was thrilling. Three Best Pictures, three years in a playing the widescreen epic comedy- A year later my brother took me to an- row: the thrill of daring men in the wide, adventure, Around the World in 80 Days. other palace, the Capitol Theater, for The wide, Todd-AO world; the horrors that I was already a regular at Saturday Bridge on the River Kwai. -

Crazy Narrative in Film. Analysing Alejandro González Iñárritu's Film

Case study – media image CRAZY NARRATIVE IN FILM. ANALYSING ALEJANDRO GONZÁLEZ IÑÁRRITU’S FILM NARRATIVE TECHNIQUE Antoaneta MIHOC1 1. M.A., independent researcher, Germany. Corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract Regarding films, many critics have expressed their dissatisfaction with narrative and its Non-linear film narrative breaks the mainstream linearity. While the linear film narrative limits conventions of narrative structure and deceives the audience’s expectations. Alejandro González Iñárritu is the viewer’s participation in the film as the one of the directors that have adopted the fragmentary narrative gives no control to the public, the narration for his films, as a means of experimentation, postmodernist one breaks the mainstream con- creating a narrative puzzle that has to be reassembled by the spectators. His films could be included in the category ventions of narrative structure and destroys the of what has been called ‘hyperlink cinema.’ In hyperlink audience’s expectations in order to create a work cinema the action resides in separate stories, but a in which a less-recognizable internal logic forms connection or influence between those disparate stories is the film’s means of expression. gradually revealed to the audience. This paper will analyse the non-linear narrative technique used by the In the Story of the Lost Reflection, Paul Coates Mexican film director Alejandro González Iñárritu in his states that, trilogy: Amores perros1 , 21 Grams2 and Babel3 . Film emerges from the Trojan horse of Keywords: Non-linear Film Narrative, Hyperlink Cinema, Postmodernism. melodrama and reveals its true identity as the art form of a post-individual society. -

Greenberg (2011)

Greenberg (2011) “You like me so much more than you think you do.” Major Credits: Director: Noah Baumbach Screenplay: Noah Baumbach, from a story by Baumbach and Jennifer Jason Leigh Cinematography: Harris Savides Music: James Murphy Principal Cast: Ben Stiller (Roger Greenberg), Greta Gerwig (Florence), Rhys Ifans (Ivan), Jennifer Jason Leigh (Beth) Production Background: Baumbach, the son of two prominent New York writers whose divorce he chronicled in his earlier feature The Squid and the Whale (2005), co-wrote the screenplay with his then-wife, Jennifer Jason Leigh, who plays the role of Greenberg’s former girlfriend. His friend and sometime collaborator (they wrote The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou together), Wes Anderson, co-produced Greenberg with Leigh. Most of Baumbach’s films to date deal with characters who are disappointed in their lives, which do not conform to their ideal conceptions of themselves. At whatever age—a father in his 40s, his pretentious teenage son (The Squid and the Whale), a college graduate in her late twenties (Frances Ha, 2012)—they struggle to act like grownups. The casting of Greta Gerwig developed into an enduring romantic and creative partnership: Gerwig co-wrote and starred in his next two films, Frances Ha and Mistress America (2015). You can read about Baumbach and Gerwig in Ian Parker’s fine article published in New Yorker, April 29, 2013. Cinematic Qualities: 1. Screenplay: Like the work of one of his favorite filmmakers, Woody Allen, Baumbach’s dramedy combines literate observation (“All the men dress up as children and the children dress as superheroes”) and bitter commentary (“Life is wasted on… people”) with poignant confession (“It’s huge to finally embrace the life you never planned on”). -

Post-Postmodern Cinema at the Turn of the Millennium: Paul Thomas Anderson’S Magnolia

Revista de Estudios Norteamericanos, vol. 24, 2020. Seville, Spain, ISSN 1133-309-X, pp. 1-21. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.12795/REN.2020.i24.01 POST-POSTMODERN CINEMA AT THE TURN OF THE MILLENNIUM: PAUL THOMAS ANDERSON’S MAGNOLIA JESÚS BOLAÑO QUINTERO Universidad de Cádiz [email protected] Received: 20 May 2020 Accepted: 26 July 2020 KEYWORDS Magnolia; Paul Thomas Anderson; post-postmodern cinema; New Sincerity; French New Wave; Jean-Luc Godard; Vivre sa Vie PALABRAS CLAVE Magnolia; Paul Thomas Anderson; cine post-postmoderno; Nueva Sinceridad; Nouvelle Vague; Jean-Luc Godard; Vivir su vida ABSTRACT Starting with an analysis of the significance of the French New Wave for postmodern cinema, this essay sets out to make a study of Paul Thomas Anderson’s Magnolia (1999) as the film that marks the beginning of what could be considered a paradigm shift in American cinema at the end of the 20th century. Building from the much- debated passing of postmodernism, this study focuses on several key postmodern aspects that take a different slant in this movie. The film points out the value of aspects that had lost their meaning within the fiction typical of postmodernism—such as the absence of causality; sincere honesty as opposed to destructive irony; or the loss of faith in Lyotardian meta-narratives. We shall look at the nature of the paradigm shift to link it to the desire to overcome postmodern values through a recovery of Romantic ideas. RESUMEN Partiendo de un análisis del significado de la Nouvelle Vague para el cine postmoderno, este trabajo presenta un estudio de Magnolia (1999), de Paul Thomas Anderson, como obra sobre la que pivota lo que se podría tratar como un cambio de paradigma en el cine estadounidense de finales del siglo XX. -

Max-Ophuls.Pdf

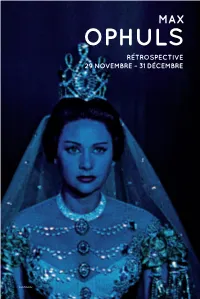

MAX OPHULS RÉTROSPECTIVE 29 NOVEMBRE – 31 DÉCEMBRE Lola Montès Divine GRAND STYLE Né en Allemagne, auteur de plusieurs mélodrames stylés en Allemagne, en Italie et en France dans les années 1930 (Liebelei, La signora di tutti, De Mayerling à Sarajevo), Max Ophuls tourne ensuite aux États-Unis des films qui tranchent par leur secrète inspiration « mitteleuropa » avec la tradition hollywoodienne (Lettre d’une inconnue). Il rentre en France et signe coup sur coup La Ronde, Le Plaisir, Madame de… et Lola Montès. Max Ophuls concevait le cinéma comme un art du spectacle. Un art de l’espace et du mouvement, susceptible de s’allier à la littérature et de s’inspirer des arts plastiques, mais un art qu’il pratiquait aussi comme un art du temps, apparen- té en cela à la musique, car il était de ceux – les artistes selon Nietzsche – qui sentent « comme un contenu, comme « la chose elle-même », ce que les non- artistes appellent la forme. » Né Max Oppenheimer en 1902, il est d’abord acteur, puis passe à la mise en scène de théâtre, avant de réaliser ses premiers films entre 1930 et 1932, l’année où, après l’incendie du Reichstag, il quitte l’Allemagne pour la France. Naturalisé fran- çais, il doit de nouveau s’exiler après la défaite de 1940, travaille quelques années aux États-Unis puis regagne la France. LES QUATRE PÉRIODES DE L’ŒUVRE CINEMATHEQUE.FR Dès 1932, Liebelei donne le ton. Une pièce d’Arthur Schnitzler, l’euphémisme de Max Ophuls, mode d’emploi : son titre, « amourette », qui désigne la passion d’une midinette s’achevant en retrouvez une sélection tragédie, et la Vienne de 1900 où la frivolité contraste avec la rigidité des codes subjective de 5 films dans la sociaux. -

The Plays in Translation

The Plays in Translation Almost all the Hauptmann plays discussed in this book exist in more or less acceptable English translations, though some are more easily available than others. Most of his plays up to 1925 are contained in Ludwig Lewisohn's 'authorized edition' of the Dramatic Works, in translations by different hands: its nine volumes appeared between 1912 and 1929 (New York: B.W. Huebsch; and London: M. Secker). Some of the translations in the Dramatic Works had been published separately beforehand or have been reprinted since: examples are Mary Morison's fine renderings of Lonely Lives (1898) and The Weavers (1899), and Charles Henry Meltzer's dated attempts at Hannele (1908) and The Sunken Bell (1899). More recent collections are Five Plays, translated by Theodore H. Lustig with an introduction by John Gassner (New York: Bantam, 1961), which includes The Beaver Coat, Drayman Henschel, Hannele, Rose Bernd and The Weavers; and Gerhart Hauptmann: Three Plays, translated by Horst Frenz and Miles Waggoner (New York: Ungar, 1951, 1980), which contains 150 The Plays in Translation renderings into not very idiomatic English of The Weavers, Hannele and The Beaver Coat. Recent translations are Peter Bauland's Be/ore Daybreak (Chapel HilI: University of North Carolina Press, 1978), which tends to 'improve' on the original, and Frank Marcus's The Weavers (London: Methuen, 1980, 1983), a straightforward rendering with little or no attempt to convey the linguistic range of the original. Wedekind's Spring Awakening can be read in two lively modem translations, one made by Tom Osbom for the Royal Court Theatre in 1963 (London: Calder and Boyars, 1969, 1977), the other by Edward Bond (London: Methuen, 1980). -

David Hare's the Blue Room and Stanley

Schnitzler as a Space of Central European Cultural Identity: David Hare’s The Blue Room and Stanley Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut SUSAN INGRAM e status of Arthur Schnitzler’s works as representative of fin de siècle Vien- nese culture was already firmly established in the author’s own lifetime, as the tributes written in on the occasion of his sixtieth birthday demonstrate. Addressing Schnitzler directly, Hermann Bahr wrote: “As no other among us, your graceful touch captured the last fascination of the waning of Vi- enna, you were the doctor at its deathbed, you loved it more than anyone else among us because you already knew there was no more hope” (); Egon Friedell opined that Schnitzler had “created a kind of topography of the constitution of the Viennese soul around , on which one will later be able to more reliably, more precisely and more richly orient oneself than on the most obese cultural historian” (); and Stefan Zweig noted that: [T]he unforgettable characters, whom he created and whom one still could see daily on the streets, in the theaters, and in the salons of Vienna on the occasion of his fiftieth birthday, even yesterday… have suddenly disappeared, have changed. … Everything that once was this turn-of-the-century Vienna, this Austria before its collapse, will at one point… only be properly seen through Arthur Schnitzler, will only be called by their proper name by drawing on his works. () With the passing of time, the scope of Schnitzler’s representativeness has broadened. In his introduction to the new English translation of Schnitzler’s Dream Story (), Frederic Raphael sees Schnitzler not only as a Viennese writer; rather “Schnitzler belongs inextricably to mittel-Europa” (xii). -

December 2018

LearnAboutMoviePosters.com December 2018 EWBANK’S AUCTIONS VINTAGE POSTER AUCTION DECEMBER 14 Ewbank's Auctions will present their Entertainment Memorabilia Auction on December 13 and Vintage Posters Auction on December 14. Star Wars and James Bond movie posters are just some of the highlights of this great auction featuring over 360 lots. See page 3. PART III ENDING TODAY - 12/13 PART IV ENDS 12/16 UPCOMING EVENTS/DEADLINES eMovieposter.com’s December Major Auction - Dec. 9-16 Part IV Dec. 13 Ewbank’s Entertainment & Memorabilia Auction Dec. 14 Ewbank’s Vintage Poster Auction Jan. 17, 2019 Aston’s Entertainment and Memorabilia Auction Feb. 28, 2019 Ewbank’s Entertainment & Memorabilia Auction Feb. 28, 2019 Ewbank’s Movie Props Auction March 1, 2019 Ewbank’s Vintage Poster Auction March 23, 2019 Heritage Auction LAMP’s LAMP POST Film Accessory Newsletter features industry news as well as product and services provided by Sponsors and Dealers of Learn About Movie Posters and the Movie Poster Data Base. To learn more about becoming a LAMP sponsor, click HERE! Add your name to our Newsletter Mailing List HERE! Visit the LAMP POST Archive to see early editions from 2001-PRESENT. The link can be found on the home page nav bar under “General” or click HERE. The LAMPPOST is a publication of LearnAboutMoviePosters.com Telephone: (504) 298-LAMP email: [email protected] Copyright 20178- Learn About Network L.L.C. 2 EWBANK’S AUCTIONS PRESENTS … ENTERTAINMENT & MEMORABILIA AUCTION - DECEMBER 13 & VINTAGE POSTER AUCTION - DECEMBER 14 Ewbank’s Auction will present their Entertainment & Memorabilia Auction on December 13 and their Vintage Poster Auction on December 14. -

Cinematic Representations of the City

UC Center French Language and Culture Program Courses – Summer 2014 PCC 105. Paris Scenes: Cinematic Representations of the City Prof. Carole Viers-Andronico Lecture contact: [email protected] Wednesday 15h00-17h00 Visits (or Lecture) Office Hours Thursday 15h00-17h00 By appointment COURSE DESCRIPTION The city of Paris has long served as muse to foreign and domestic filmmakers. Cinematic representations have framed and reframed not only how we see and understand many of the ville lumière’s most famous monuments and districts but also how we comprehend aspects of French history and culture. This course, therefore, will take an interdisciplinary approach to cinematic representation by relying on methodologies from comparative literature, philosophies of aesthetics, film studies, history, and urban studies. Throughout the course, students will study the ways in which cinematic representations attribute meaning to monuments and districts. They will analyze how these representations constitute scenes of re-presentation; that is, how they provide interpretations of cultural, historical, and socio-political events. Through a combination of viewings, related readings, and site visits to scene locations, students will engage in discussions about how the meanings of such sites become manifold depending on how they are framed and thus seen/scened. The course will be organized around case studies of both well-known and lesser-known sites, such as the Eiffel Tower, the Montmartre district, and the Latin Quarter district. 4.0 UC quarter units. Suggested subject areas for this course: Film / Comparative Literature / Urban Studies Goals The overriding goal of this course is to provide students with the tools to reflect critically on cinematic representations of Paris as a city in history. -

MGM 70 YEARS: REDISCOVERIES and CLASSICS June 24 - September 30, 1994

The Museum of Modern Art For Immediate Release May 1994 MGM 70 YEARS: REDISCOVERIES AND CLASSICS June 24 - September 30, 1994 A retrospective celebrating the seventieth anniversary of Metro-Goldwyn- Mayer, the legendary Hollywood studio that defined screen glamour and elegance for the world, opens at The Museum of Modern Art on June 24, 1994. MGM 70 YEARS: REDISCOVERIES AND CLASSICS comprises 112 feature films produced by MGM from the 1920s to the present, including musicals, thrillers, comedies, and melodramas. On view through September 30, the exhibition highlights a number of classics, as well as lesser-known films by directors who deserve wider recognition. MGM's films are distinguished by a high artistic level, with a consistent polish and technical virtuosity unseen anywhere, and by a roster of the most famous stars in the world -- Joan Crawford, Clark Gable, Judy Garland, Greta Garbo, and Spencer Tracy. MGM also had under contract some of Hollywood's most talented directors, including Clarence Brown, George Cukor, Vincente Minnelli, and King Vidor, as well as outstanding cinematographers, production designers, costume designers, and editors. Exhibition highlights include Erich von Stroheim's Greed (1925), Victor Fleming's Gone Hith the Hind and The Wizard of Oz (both 1939), Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), and Ridley Scott's Thelma & Louise (1991). Less familiar titles are Monta Bell's Pretty Ladies and Lights of Old Broadway (both 1925), Rex Ingram's The Garden of Allah (1927) and The Prisoner - more - 11 West 53 Street, New York, N.Y. 10019-5498 Tel: 212-708-9400 Cable: MODERNART Telex: 62370 MODART 2 of Zenda (1929), Fred Zinnemann's Eyes in the Night (1942) and Act of Violence (1949), and Anthony Mann's Border Incident (1949) and The Naked Spur (1953).