The Rise of Johnnie to by Marie Jost

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

See It Big! Action Features More Than 30 Action Movie Favorites on the Big

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE ‘SEE IT BIG! ACTION’ FEATURES MORE THAN 30 ACTION MOVIE FAVORITES ON THE BIG SCREEN April 19–July 7, 2019 Astoria, New York, April 16, 2019—Museum of the Moving Image presents See It Big! Action, a major screening series featuring more than 30 action films, from April 19 through July 7, 2019. Programmed by Curator of Film Eric Hynes and Reverse Shot editors Jeff Reichert and Michael Koresky, the series opens with cinematic swashbucklers and continues with movies from around the world featuring white- knuckle chase sequences and thrilling stuntwork. It highlights work from some of the form's greatest practitioners, including John Woo, Michael Mann, Steven Spielberg, Akira Kurosawa, Kathryn Bigelow, Jackie Chan, and much more. As the curators note, “In a sense, all movies are ’action’ movies; cinema is movement and light, after all. Since nearly the very beginning, spectacle and stunt work have been essential parts of the form. There is nothing quite like watching physical feats, pulse-pounding drama, and epic confrontations on a large screen alongside other astonished moviegoers. See It Big! Action offers up some of our favorites of the genre.” In all, 32 films will be shown, many of them in 35mm prints. Among the highlights are two classic Technicolor swashbucklers, Michael Curtiz’s The Adventures of Robin Hood and Jacques Tourneur’s Anne of the Indies (April 20); Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai (April 21); back-to-back screenings of Mad Max: Fury Road and Aliens on Mother’s Day (May 12); all six Mission: Impossible films -

Just As the Priests Have Their Wives”: Priests and Concubines in England, 1375-1549

“JUST AS THE PRIESTS HAVE THEIR WIVES”: PRIESTS AND CONCUBINES IN ENGLAND, 1375-1549 Janelle Werner A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2009 Approved by: Advisor: Professor Judith M. Bennett Reader: Professor Stanley Chojnacki Reader: Professor Barbara J. Harris Reader: Cynthia B. Herrup Reader: Brett Whalen © 2009 Janelle Werner ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT JANELLE WERNER: “Just As the Priests Have Their Wives”: Priests and Concubines in England, 1375-1549 (Under the direction of Judith M. Bennett) This project – the first in-depth analysis of clerical concubinage in medieval England – examines cultural perceptions of clerical sexual misbehavior as well as the lived experiences of priests, concubines, and their children. Although much has been written on the imposition of priestly celibacy during the Gregorian Reform and on its rejection during the Reformation, the history of clerical concubinage between these two watersheds has remained largely unstudied. My analysis is based primarily on archival records from Hereford, a diocese in the West Midlands that incorporated both English- and Welsh-speaking parishes and combines the quantitative analysis of documentary evidence with a close reading of pastoral and popular literature. Drawing on an episcopal visitation from 1397, the act books of the consistory court, and bishops’ registers, I argue that clerical concubinage occurred as frequently in England as elsewhere in late medieval Europe and that priests and their concubines were, to some extent, socially and culturally accepted in late medieval England. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Queerness and Chinese Modernity: the Politics of Reading Between East and East a Dissertati

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Queerness and Chinese Modernity: The Politics of Reading Between East and East A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Literature by Alvin Ka Hin Wong Committee in Charge: Professor Yingjin Zhang, Co-Chair Professor Lisa Lowe, Co-Chair Professor Patrick Anderson Professor Rosemary Marangoly George Professor Larissa N. Heinrich 2012 Copyright Alvin Ka Hin Wong, 2012 All rights reserved. The dissertation of Alvin Ka Hin Wong is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ Co-Chair ________________________________________________________________________ Co-Chair University of California, San Diego 2012 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page …………………………………………………….……………….….…iii Table of Contents ………………………………………………………………..…….…iv List of Illustrations ……………………………………………………………….…........v Acknowledgments …………………………………………………………………….....vi Vita …………………………………………………….…………………………….…...x Abstract of the Dissertation ………………………………………………….……….….xi INTRODUCTION.……………………………………………………………….……....1 CHAPTER ONE. Queering Chineseness and Kinship: Strategies of Rewriting by Chen Ran, Chen Xue and Huang Biyun………………………….………...33 -

The New Hong Kong Cinema and the "Déjà Disparu" Author(S): Ackbar Abbas Source: Discourse, Vol

The New Hong Kong Cinema and the "Déjà Disparu" Author(s): Ackbar Abbas Source: Discourse, Vol. 16, No. 3 (Spring 1994), pp. 65-77 Published by: Wayne State University Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/41389334 Accessed: 22-12-2015 11:50 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/ info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Wayne State University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Discourse. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 142.157.160.248 on Tue, 22 Dec 2015 11:50:37 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions The New Hong Kong Cinema and the Déjà Disparu Ackbar Abbas I For about a decade now, it has become increasinglyapparent that a new Hong Kong cinema has been emerging.It is both a popular cinema and a cinema of auteurs,with directors like Ann Hui, Tsui Hark, Allen Fong, John Woo, Stanley Kwan, and Wong Rar-wei gaining not only local acclaim but a certain measure of interna- tional recognitionas well in the formof awards at international filmfestivals. The emergence of this new cinema can be roughly dated; twodates are significant,though in verydifferent ways. -

The Whistleblowers

A U S F I L M Australian Familiarisation Event Mathew Tang Producer Mathew Tang began his career in 1989 and has since worked on over 30 feature films, covering various creative and production duties that include assistant directing, line-producing, writing, directing and producing. In 1999, Mathew debuted as a screenwriter on The Kid, a film that went on to win Best Supporting Actor and Actress in the Hong Kong Film Awards. In 2005, he wrote, edited and directed his debut feature B420 which received The Grand Prix Award at the 19th Fukuoka Asian Film Festival and Best Film at the 4th Viennese Youth International Film Festival in 2007. Mathew served as Associate Producer and Line Producer on Forbidden Kingdom and oversaw the Hollywood blockbuster’s entire production in China. In 2008 and 2009 he was Vice President of Celestial Pictures. From 2009- 2012, he was the Head of Productions at EDKO Films Ltd. In the summer of 2012, he founded Movie Addict Productions and the company produced four movies. Mathew is currently an Invited Executive Member of the Hong Kong Screenwriters’ Guild and a Panel Examiner of the Hong Kong Film Development Council. Johnny Wang Line Producer Johnny Wang started working for the movie industry in 1989 and by the year 2002, he started working at Paramount Studios on the project Tomb Raider 2 as production supervisor on location in Hong Kong. Since then, he has line produced 20 movies in Hong Kong, China and other locations around the world. Johnny has been an executive board member of the HKMPEA (Hong Kong Movie Production Executives Association) for more than four years. -

Johnnie to Kei-Fung's

JOHNNIE TO KEI-FUNG’S PTU Michael Ingham Hong Kong University Press The University of Hong Kong Pokfulam Road Hong Kong www.hkupress.org © 2009 Michael Ingham ISBN 978-962-209-919-7 All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed and bound by Pre-Press Ltd. in Hong Kong, China Contents Series Preface vii Acknowledgements xi 1 Introducing the Film; Introducing Johnnie — 1 ‘One of Our Own’ 2 ‘Into the Perilous Night’ — Police and Gangsters 35 in the Hong Kong Mean Streets 3 ‘Expect the Unexpected’ — PTU’s Narrative and Aesthetics 65 4 The Coda: What’s the Story? — Morning Glory! 107 Notes 127 Appendix 131 Credits 143 Bibliography 147 ●1 Introducing the Film; Introducing Johnnie — ‘One of Our Own’ ‘It is not enough to think about Hong Kong cinema simply in terms of a tight commercial space occasionally opened up by individual talent, on the model of auteurs in Hollywood. The situation is both more interesting and more complicated.’ — Ackbar Abbas, Hong Kong Culture and the Politics of Disappearance ‘Yet many of Hong Kong’s most accomplished fi lms were made in the years after the 1993 downturn. Directors had become more sophisticated, and perhaps fi nancial desperation freed them to experiment … The golden age is over; like most local cinemas, Hong Kong’s will probably consist of a small annual output and a handful of fi lms of artistic interest. -

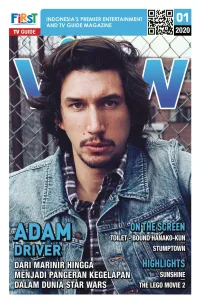

View 202001.Pdf

ON THE SCREEN Premieres Wednesday, January 8 10.10 PM juga adik lelakinya. Di lain sisi, Dex Parios juga berjuang dari rasa traumatis yang ia dapat setelah bertugas sebagai marinir di Afghanistan. Saat itu Premieres, Tuesday ketika ia sedang bertugas sebagai intelijen militer, Dex Parios mengalami ledakan yang membuatnya January 21, 8 PM terluka, dan harus kehilangan orang yang ia cintai. Sementara ia meninggalkan pekerjaannya, ia Sebuah serial televisi Amerika yang pun memutuskan untuk bekerja serabutan demi bertemakan drama kriminal. Dibintangi menghidupi dirinya dan juga adiknya. Hingga oleh Cobie Smulders, Jake Johnson dan pada saatnya, Dex Parios bekerja sebagai Michael Ealy. penyelidik swasta dimana ia bertugas untuk menyelidiki masalah yang tidak bisa dicampuri Teks: Klement Galuh A oleh kepolisian. Dalam perjuangannya tersebut, ia pun mendapat dukungan dari seorang detektif ada serial ini bercerita tentang Dex Parios, bernama Miles Hoffman dan juga Gray McConnel seorang veteran militer cerdas, yang hidup yang mempekerjakan saudara lelaki Dex Parios di P dan berjuang untuk menghidupi dirinya dan bar miliknya. (LMN/MHG/LMN/FIO) 4 Acara “Sacred Sites”, kita diajak untuk mengunjungi tempat-tempat bersejarah yang masih menjadi rahasia dan misteri bagi umat manusia. Kita akan diajak untuk menemukan jawaban-jawaban tersebut melalui acara ini. Teks: Klement Galuh A pakah benar legenda raja Arthur nyata adanya? Pertanyaan tersebut akan dikupas menggunakan A terobosan ilmiah dan penelitian arkeologis untuk membawa kita kepada perspektif baru ke beberapa lokasi religi yang luar biasa, namun juga misterius. Dalam setiap episodenya, acara ini akan berfokus pada satu situs dan mengeksplorasi situs tersebut. Dimulai dari orang-orang yang membangunnya, hingga menjawab pertanyaan mendasar dari orang-orang yang melihat bangunan tersebut. -

Sungkyun Journal of East Asian Studies

Sungkyun Journal of East Asian Studies On the Rooftop: A Study of Marginalized Youth Films in Hong Kong Cinema Xuelin ZHOU University of Auckland Sungkyun Journal of East Asian Studies. Vol. 8, No. 2 ⓒ 2008 Academy of East Asia Studies. pp.163-177 You may use content in the SJEAS back issues only for your personal, non-commercial use. Contents of each article do not represent opinions of SJEAS. Sungkyun Journal of East Asian Studies. Vol.8, No.2. � 2008 Academy of East Asian Studies. pp.163-177 On the Rooftop: A Study of Marginalized Youth Films in Hong Kong Cinema1 Xuelin ZHOU University of Auckland ABSTRACT Researchers of contemporary Hong Kong cinema have tended to concentrate on the monumental, metropolitan and/or historical works of such esteemed directors as Wong Kar-Wai, John Woo and Tsui Hark. This paper focuses instead on a number of low-budget films that circulated below the radar of Chinese as well as Western film scholars but were important to local young viewers, i.e. a cluster of films that feature deviant and marginalized youth as protagonists. They are very interesting as evidence of perceived social problems in contemporary Hong Kong. The paper aims to outline some main features of these marginalized youth films produced since the mid-1990s. Keywords: Hong Kong, cinema, youth culture, youth film, marginalized youth On the Rooftop A scene set on the rooftop of a skyscraper in central Hong Kong appears in New Police Story(2004), or Xin jingcha gushi, by the Hong Kong director Benny Chan, an action drama that features an aged local police officer struggling to fight a group of trouble-making, tech-savvy teenagers.2 The young people are using the rooftop for an “X-party,” an occasion for showing off their skills of skateboarding and cycling, by doing daredevil stunts along the edge of the building. -

Great Cloud of Witnesses.Indd

A Great Cloud of Witnesses i ii A Great Cloud of Witnesses A Calendar of Commemorations iii Copyright © 2016 by The Domestic and Foreign Missionary Society of The Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States of America Portions of this book may be reproduced by a congregation for its own use. Commercial or large-scale reproduction for sale of any portion of this book or of the book as a whole, without the written permission of Church Publishing Incorporated, is prohibited. Cover design and typesetting by Linda Brooks ISBN-13: 978-0-89869-962-3 (binder) ISBN-13: 978-0-89869-966-1 (pbk.) ISBN-13: 978-0-89869-963-0 (ebook) Church Publishing, Incorporated. 19 East 34th Street New York, New York 10016 www.churchpublishing.org iv Contents Introduction vii On Commemorations and the Book of Common Prayer viii On the Making of Saints x How to Use These Materials xiii Commemorations Calendar of Commemorations Commemorations Appendix a1 Commons of Saints and Propers for Various Occasions a5 Commons of Saints a7 Various Occasions from the Book of Common Prayer a37 New Propers for Various Occasions a63 Guidelines for Continuing Alteration of the Calendar a71 Criteria for Additions to A Great Cloud of Witnesses a73 Procedures for Local Calendars and Memorials a75 Procedures for Churchwide Recognition a76 Procedures to Remove Commemorations a77 v vi Introduction This volume, A Great Cloud of Witnesses, is a further step in the development of liturgical commemorations within the life of The Episcopal Church. These developments fall under three categories. First, this volume presents a wide array of possible commemorations for individuals and congregations to observe. -

Download This PDF File

Humanity 2012 Papers. ~~~~~~ “‘We are all the same, we are all unique’: The paradox of using individual celebrity as metaphor for national (transnational) identity.” Joyleen Christensen University of Newcastle Introduction: This paper will examine the apparently contradictory public persona of a major star in the Hong Kong entertainment industry - an individual who essentially redefined the parameters of an industry, which is, itself, a paradox. In the last decades of the 20th Century, the Hong Kong entertainment industry's attempts to translate American popular culture for a local audience led to an exciting fusion of cultures as the system that was once mocked by English- language media commentators for being equally derivative and ‘alien’, through translation and transmutation, acquired a unique and distinctively local flavour. My use of the now somewhat out-dated notion of East versus West sensibilities will be deliberate as it reflects the tone of contemporary academic and popular scholarly analysis, which perfectly seemed to capture the essence of public sentiment about the territory in the pre-Handover period. It was an explicit dichotomy, with commentators frequently exploiting the notion of a culture at war with its own conception of a national identity. However, the dwindling Western interest in Hong Kong’s fate after 1997 and the social, economic and political opportunities afforded by the reunification with Mainland China meant that the new millennia saw Hong Kong's so- called ‘Culture of Disappearance’ suddenly reconnecting with its true, original self. Humanity 2012 11 Alongside this shift I will track the career trajectory of Andy Lau – one of the industry's leading stars1 who successfully mimicked the territory's movement in focus from Western to local and then regional. -

Donnie Yen's Kung Fu Persona in Hypermedia

Studies in Media and Communication Vol. 4, No. 2; December 2016 ISSN 2325-8071 E-ISSN 2325-808X Published by Redfame Publishing URL: http://smc.redfame.com Remediating the Star Body: Donnie Yen’s Kung Fu Persona in Hypermedia Dorothy Wai-sim Lau1 113/F, Hong Kong Baptist University Shek Mun Campus, 8 On Muk Street, Shek Mun, Shatin, Hong Kong Correspondence: Dorothy Wai-sim Lau, 13/F, Hong Kong Baptist University Shek Mun Campus, 8 On Muk Street, Shek Mun, Shatin, Hong Kong. Received: September 18, 2016 Accepted: October 7, 2016 Online Published: October 24, 2016 doi:10.11114/smc.v4i2.1943 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.11114/smc.v4i2.1943 Abstract Latest decades have witnessed the proliferation of digital media in Hong Kong action-based genre films, elevating the graphical display of screen action to new levels. While digital effects are tools to assist the action performance of non-kung fu actors, Dragon Tiger Gate (2006), a comic-turned movie, becomes a case-in-point that it applies digitality to Yen, a celebrated kung fu star who is famed by his genuine martial dexterity. In the framework of remediation, this essay will explore how the digital media intervene of the star construction of Donnie Yen. As Dragon Tiger Gate reveals, technological effects work to refashion and repurpose Yen’s persona by combining digital effects and the kung fu body. While the narrative of pain and injury reveals the attempt of visual immediacy, the hybridized bodily representation evokes awareness more to the act of representing kung fu than to the kung fu itself. -

Award-Winning Hong Kong Film Gallants to Premiere at Hong Kong

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Award-winning Hong Kong film Gallants to premiere at Hong Kong Film Festival 2011 in Singapore One-week festival to feature a total of 10 titles including four new and four iconic 1990s Hong Kong films of action and romance comedy genres Singapore, 30 June 2011 – Movie-goers can look forward to a retro spin at the upcoming Hong Kong Film Festival 2011 (HKFF 2011) to be held from 14 to 20 July 2011 at Cathay Cineleisure Orchard. A winner of multiple awards at the Hong Kong Film Awards 2011, Gallants, will premiere at HKFF 2011. The action comedy film will take the audience down the memory lane of classic kung fu movies. Other new Hong Kong films to premiere at the festival include action drama Rebellion, youthful romance Breakup Club and Give Love. They are joined by retrospective titles - Swordsman II, Once Upon A Time in China II, A Chinese Odyssey: Pandora’s Box and All’s Well, Ends Well. Adding variety to the lineup is Quattro Hong Kong I and II, comprising a total of eight short films by renowned Hong Kong and Asian filmmakers commissioned by Brand Hong Kong and produced by the Hong Kong International Film Festival Society. The retrospective titles were selected in a voting exercise that took place via Facebook and SMS in May. Public were asked to select from a list of iconic 1990s Hong Kong films that they would like to catch on the big screen again. The list was nominated by three invited panelists, namely Randy Ang, local filmmaker; Wayne Lim, film reviewer for UW magazine; and Kenneth Kong, film reviewer for Radio 100.3.