University of Cincinnati

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Feasting in Homeric Epic 303

HESPERIA 73 (2004) FEASTING IN Pages 301-337 HOMERIC EPIC ABSTRACT Feasting plays a centralrole in the Homeric epics.The elements of Homeric feasting-values, practices, vocabulary,and equipment-offer interesting comparisonsto the archaeologicalrecord. These comparisonsallow us to de- tect the possible contribution of different chronologicalperiods to what ap- pearsto be a cumulative,composite picture of around700 B.c.Homeric drink- ing practicesare of particularinterest in relation to the history of drinkingin the Aegean. By analyzing social and ideological attitudes to drinking in the epics in light of the archaeologicalrecord, we gain insight into both the pre- history of the epics and the prehistoryof drinkingitself. THE HOMERIC FEAST There is an impressive amount of what may generally be understood as feasting in the Homeric epics.' Feasting appears as arguably the single most frequent activity in the Odysseyand, apart from fighting, also in the Iliad. It is clearly not only an activity of Homeric heroes, but also one that helps demonstrate that they are indeed heroes. Thus, it seems, they are shown doing it at every opportunity,to the extent that much sense of real- ism is sometimes lost-just as a small child will invariablypicture a king wearing a crown, no matter how unsuitable the circumstances. In Iliad 9, for instance, Odysseus participates in two full-scale feasts in quick suc- cession in the course of a single night: first in Agamemnon's shelter (II. 1. thanks to John Bennet, My 9.89-92), and almost immediately afterward in the shelter of Achilles Peter Haarer,and Andrew Sherrattfor Later in the same on their return from their coming to my rescueon variouspoints (9.199-222). -

University Microfilms International

ANCIENT EUBOEA: STUDIES IN THE HISTORY OF A GREEK ISLAND FROM EARLIEST TIMES TO 404 B.C. Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Vedder, Richard Glen, 1950- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 11/10/2021 05:15:39 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/290465 INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. -

Kate Bracher — Travels in Greece Ever Since the Year 2000, I Have Had to Go to Greece Every Summer for 4- 6 Weeks. (I Can

Kate Bracher — Travels in Greece Ever since the year 2000, I have had to go to Greece every summer for 4- 6 weeks. (I can hear you saying, “aw, too bad!”) This is because my partner, Cynthia Shelmerdine (Bryn Mawr ’70) is an archaeologist working on a project in the southwest of the Peloponnese. They are digging a Mycenaean town, which dates to the Late Bronze Age (1700-1200 BC), near the town of Pylos. This is way before the time period we tend to think of for ancient Greece — the age of Socrates, Plato, Pericles, Sophocles — and is basically the period Homer thinks he’s writing about 600 years later. The project is directed by a professor from the University of Missouri at St. Louis; he runs it as a field school, so most years there are about 30 students working on the dig. (You can see a slightly out-of- date discussion of it at the project website, iklaina.org.) Cynthia is their pottery expert; so she is not in the field but in the lab room in the small town of Pylos, where we are based. The diggers collect potsherds and other artifacts, and bring them in each day; the pottery gets washed, dried in the sun, and then Cynthia can look at it and identify what the pieces are and when they were made. It’s amazing how much you can tell from a 2-inch broken rim of a drinking cup or bowl! At first I just tagged along (because who would turn down a chance to go to Greece!) But gradually I got roped in also, and worked for years as the lab’s organizer, logging in bags of potsherds as they arrived, shepherding them through the washing, drying and study process, and eventually seeing that they were stored where someone could find them again if they need to. -

Chariot Usage in Greek Dark Age Warfare Carolyn Nicole Conter

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2003 Chariot Usage in Greek Dark Age Warfare Carolyn Nicole Conter Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES CHARIOT USAGE IN GREEK DARK AGE WARFARE By CAROLYN NICOLE CONTER A thesis submitted to the Department of Classics in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2003 The members of the Committee approve the thesis of Carolyn Nicole Conter defended on October 23, 2003. _______________________ Chistopher A. Pfaff Professor Directing Thesis _______________________ Daniel J. Pullen Committee Member ______________________ Kathryn B. Stoddard Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii To Mom and Dad, for your patience, encouragement and steadfast support. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express appreciation to Dr. Christopher Pfaff, who directed my thesis. Thank you for your unceasing patience and guidance through the thesis process and throughout my graduate studies. I would also like to extend gratitude to Dr. Daniel Pullen for always challenging me throughout my undergraduate and graduate studies and for providing an avenue for me to strive to do my best. Gratitude is also expressed for Dr. Kathryn Stoddard for her helpful and positive remarks that have given me much needed encouragement. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures .............................................................................................. vi Abstract ........................................................................................................ ix INTRODUCTION......................................................................................... 1 1. PHYSICAL EVIDENCE FOR CHARIOTS DATING TO THE GREEK BRONZE AGE AND DARK AGE...................... -

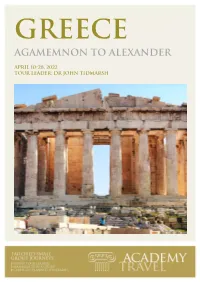

Agamemnon to Alexander

GREECE AGAMEMNON TO ALEXANDER APRIL 10-28, 2022 TOUR LEADER: DR JOHN TIDMARSH GREECE Overview AGAMEMNON TO ALEXANDER During our travels we shall visit many of the great sites of ancient and Tour dates: April 10-28, 2022 medieval Greece while focussing on two vital eras in its rich history, namely the world of the Aegean Bronze Age and that of the Macedonian Tour leader: Dr John Tidmarsh rulers Philip and his son Alexander (the Great), whose exploits altered the ancient world forever. Tour Price: $10,595 per person, twin share It is during the Aegean Bronze Age (c.3000-1000 BC) that we see the rise and fall of two of the most remarkable (and enigmatic) civilizations— Single Supplement: $2,295 for sole use of Minoan and Mycenaean—of the ancient world. In Crete we explore the double room sprawling palace of King Minos at Knossos, home to the legendary Minotaur, along with the lesser known but equally fascinating Minoan Booking deposit: $1000 per person palaces of Malia and Phaistos and the charming and well-preserved Recommended airline: Emirates Minoan village of Gournia, unearthed by the extraordinary American Harriet Boyd Hawes, the first woman to lead an archaeological excavation in the Aegean. Maximum places: 20 From Crete we then travel to Athens, home to the Acropolis, ancient Itinerary: Athens (1 night), Heraklion (3 nights), Agora, and a host of superbly laid out museums. From Athens (also a Athens (2 nights), Nafplio (2 nights), Pylos (2 Mycenaean stronghold, the remains of which are still visible) it is on to the nights), Olympia (1 night), Delphi (2 nights), Peloponnese, where we enter the world of Agamemnon and the warrior Volos (1 night), Thessaloniki (4 nights) Mycenaean kings who dominated Greece from their awe-inspiring palaces at Mycenae, Tiryns, and Pylos (all of which we visit) until their civilization Date published: December 18, 2020 mysteriously collapsed at the end of the Bronze Age. -

An Archer from the Palace of Nestor 365

hesperia 77 (2008) An Archer from the Pages 363–397 Palace of Nestor A New Wall-Painting Fragment in the Chora Museum Dedicated to Mabel L. Lang ABSTRACT The authors interpret two joining pieces of a brightly colored wall painting found at the Palace of Nestor in 1939. The fragment, removed from the walls of the palace prior to its final destruction, represents part of an archer, prob- ably female. Alternative reconstructions are offered. Artistic methods and constituents of the plaster and paint are studied by XRD, PIXE-alpha analysis, XRF, SEM-EDS, PY/GC-MS, and GC-MS. Egyptian blue pigment was extensively employed. Egg was used as a binder for the pigments in a tempera, rather than a fresco, technique. The identification of individualized painting styles may make it possible to assign groups of wall paintings to particular artists or workshops. Restudy of the many published and unpublished wall-painting fragments from the Palace of Nestor in Pylos that are stored in the Chora Museum began in 2000.1 By 2002 it was possible to make a full assessment of the corpus and to define directions for future work. In the course of earlier examinations and the systematic arrangement of wall paintings in new storage cabinets, an unpublished piece of special interest was discovered. 1. A reexamination of the corpus of Muhly, former director of the Ameri- described here has been provided by the wall paintings from the Palace of can School of Classical Studies at Institute for Aegean Prehistory, the Nestor is part of the program of the Athens, and to Maria Pilali for facilita- Semple Fund of the Department of Hora Apotheke Reorganization Project ting our work in every way. -

Erwin COOK and Thomas PALAIMA New Perspectives on Pylian Cults Sacrifice and Society in the 'Odyssey' We Here Address a Tendency

Erwin COOK and Thomas PALAIMA New Perspectives on Pylian Cults Sacrifice and Society in the 'Odyssey' We here address a tendency in modern scholarship to treat "Homeric Society" as monolithic. We also address the Grote-like 'rationalist' reaction to the Homeromania that prevailed in the study of the Linear B documents and Mycenaean archaeology in the years that followed the Ventris decipherment. We argue that Homer presents a more variegated view of the Greek world than is generally accepted. We identify important narrative reasons for this, but we also suggest that Homer's description of Nestor's Pylos includes distinctive features of the Bronze Age palatial culture that once existed on the acropolis at Ano Englianos that were preserved through a living tradition ultimately derived from the post-Mycenaean inhabitants of Messenia. The Pylian narrative in Homer is organized as a series of religious rituals bracketed by an arrival and departure scene. Telemakhos arrives at Pylos to encounter ritual feasting on a scale without precedent in Homer. Special prominence is awarded libation rituals and libation vessels, described interchangeably as depas and aleison. Both seem to be non- or pre-Greek loan words. A number of elements of the physical description help lend Homeric Pylos a BA patina, including most famously the political organization of Pylos as a confederation of nine cities under palatial control. To them can now be added Homer's presentation of the Pylian wanax. The centrality of cult to the ideology of the wanax has been demonstrated from the full Linear B textual documentation from the site of Pylos and the iconographical and architectural program of the Palace of Nestor. -

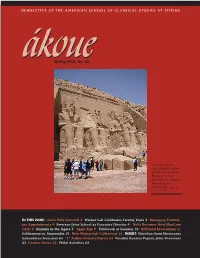

Spring 2012 (No

NEWSLETTER OF THE AMERICAN SCHOOL OF CLASSICAL STUDIES AT ATHENS ákoueákoueSpring 2012, No. 66 Students look for Greek graffiti at Abu Simbel. The Academic Program took an optional trip to Egypt this spring. See related story on p. 9. Photo M.M. Miles IN THIS ISSUE: Davis Bids Farewell 2 Wiener Lab Celebrates Twenty Years 3 Managing Commit- tee Appoint ments 4 Emerson Joins School as Executive Director 4 Neils Becomes Next ManCom Chair 5 Animals in the Agora 7 Egypt Trip 9 Fieldwork at Sounion 10 Affiliated Excavations 11 Schliemann vs. Stamatakis 15 New Wiener Lab Collections 16 INSERT: Niarchos Grant Showcases Gennadeion Treasures G1 “Z” Author Donates Papers G1 Vovolini Donates Papers, Joins Overseers G2 Lecture Series G3 Philoi Activities G4 Davis Bids Farewell It seems just yesterday that ákoue printed notice of my arrival in Athens and that an interview with me was posted on the School’s web site (www.ascsa.edu.gr), then still new. I was thus reluctant to write a farewell for this issue, not least because the thought of leaving Souidias 54 saddens me. I will miss waking to the chatter of birds in the garden, smelling the wisteria and the ákoue! bitter oranges in bloom, but above all the constant bustle of members and visitors coming and going, thousands each year. Many have become dear friends. I can’t believe how little I knew about ASCSA before assuming my post, or how much I now know about the academic, intellectual, and social communities in Greece in which we play such an impor- tant role. -

Carl W. Blegen Journal 1 1 Journal of Finds and References. Excavation

Item 1 Date Created Date Edited 1/16/2004 folder # 1 item # Date October 1920 - 1927? Author Carl W. Blegen Recipient Location Athens Material Type journal # of Pages Subject Journal of finds and references. Keywords excavation; Pylos; Amorgos; Paros; Syra; Phylakopi; Mycenaean Notes Item 2 Date Created 9/23/2003 Date Edited 10/29/2003 folder # 2 item # Date 1/12/1925 Author R. B. Seager Recipient Carl W. Blegen Location Singapore Material Type postcard # of Pages 1 Subject Description of Seager's travels in Asia. Keywords Asia Notes Item 3 Date Created 9/23/2003 Date Edited 11/3/2003 folder # 3 item # Date 4/13/1925 Author Richard Seager Recipient Carl W. Blegen Location Sakhara Material Type correspondence # of Pages 2 Subject Seager inquires if Blegen or Hill are returning to the United States that summer and when. Seager mentions the shooting of one of Blegen's students near Arta. Keywords Crete; Greece; Bert Hodge Hill; Alan J. B. Wace; Kendrick Notes Item 4 Date Created 9/23/2003 Date Edited 1/16/2004 folder # 4 item # Date 9/10/1926 Author Bert Hodge Hill Recipient William K P Location Corinth Material Type correspondence # of Pages 4 Subject Hill describes his problems with Edward Capps about the Gennadeion Library and other ASCSA directorship issues. Keywords ASCSA; Gennadeion Library; Notes includes portions of earlier correspondence between BHH, E.Capps, and J.R. Wheeler Item 5 Date Created 9/23/2003 Date Edited 11/19/2003 folder # 5 item # Date 12/22/1926 Author Bert Hodge Hill Recipient Carl W. -

Archaeology Magazine

ver since Heinrich Schliemann began digging at the ancient Greek site of Mycenae in 1876, generations of archaeologists have worked to uncover the spectacular remains of a Bronze Age superpower that gave its name to a whole civilization. The “Mycenaeans” were not a single people, but disparate groups united by a shared culture that stretched all over Greece and dominated the Aegean in the Late Bronze Age, from about 1600 to 1100 b.c. This was the world of the Trojan War; scholars believe Homer’s E Iliad describes actual events involving Mycenaean city-states around 1200 b.c. For many ancient writers and some modern excavators, Homer’s kings and warriors were based on historical figures who set out for Troy from the citadels that still bear their ancient names—Pylos, Tiryns, Argos, Thebes, and chief among them, Mycenae. Not surprisingly, archaeologists have focused their efforts on uncovering evidence of the elite society ruled by kings, including Agamemnon at Mycenae and Nestor at Pylos. But one energetic young scholar is turning away from the kings and focusing on the regular people of ancient Mycenae. Despite more than a century of excavation at the Mycenaean palace sites, no one has ever excavated a Mycenaean town. Christofilis Maggidis and his team are determined to change that. If he succeeds, questions about Search for the Mycenaeans Closing in on the people and towns of Homer’s Greece by Jarrett A. Lobell Mycenae and other palace sites thought to be similar in sociopolitical organization, can be addressed for the first time. How did trade function outside the strict commercial system regulated by the palace? What was day-to-day social and economic life like? What kind of houses did the Mycenaeans live in and what did they eat? We know that the Mycenaean elite flourished thanks to their control of rich farm- land and ample food supplies, which were protected by rugged mountain ranges. -

Feasting at Nestor's Palace at Pylos

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Nebraska Anthropologist Anthropology, Department of 2006 Feasting at Nestor's Palace at Pylos Deanna L. Wesolowski Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nebanthro Part of the Anthropology Commons Wesolowski, Deanna L., "Feasting at Nestor's Palace at Pylos" (2006). Nebraska Anthropologist. 26. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nebanthro/26 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Anthropology, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Nebraska Anthropologist by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Feasting at Nestor's Palace at Pylos Deanna L. Wesolowski Abstract: Early in the excavation of Nestor's palace at Pylos it was apparent that the palace was a place of large-scale communal feasting. Both Homer's literary account ofNestor 'sf east sf rom the Odyssey and the overwhelming number of kylikes in the pantry rooms provided obvious evidence of this. It has only been later, after the decipherment of Linear B and reconstruction of the megaron frescoes that the purposes, reasons, and organization of the feasts began to be explored. This paper will examine the physical remains, specifically the pottery from the pantries, the wine magazine, and the faunal evidence along with the interpretive evidence found in the Linear B documents and megaron frescoes, to reveal a hierarchical society that offered sacrifices to Poseidon shortly before it destruction. The feasts of the society will then be considered in a simple anthropological context, so the feasts move from the realm of Bronze Age Greece to the larger sphere ofcommon human behaviors. -

Spatial Diversity of Cr Distribution in Soil and Groundwater Sites in Relation with Land Use Management in a Mediterranean Region: the Case of C

Science of the Total Environment 651 (2019) 656–667 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Science of the Total Environment journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/scitotenv Spatial diversity of Cr distribution in soil and groundwater sites in relation with land use management in a Mediterranean region: The case of C. Evia and Assopos-Thiva Basins, Greece Ifigeneia Megremi, Charalampos Vasilatos ⁎, Emmanuel Vassilakis, Maria Economou-Eliopoulos Department of Geology and Geoenvironment, University of Athens, Athens 15784, Greece HIGHLIGHTS GRAPHICAL ABSTRACT • Spatial distribution of Cr and other ele- ments in an area of Greece investigated • Maps of land use and element contents in soil and groundwater were devel- oped. • GIS and multivariate statistics were ap- plied to assess the origin of Cr contami- nation. • Maps help distinguish Cr of geogenic and anthropogenic origin and saliniza- tion. • These provide information for sustain- able land management. article info abstract Article history: The present study compiles new and literature data in a GIS platform aiming to (a) evaluate the extent and mag- Received 4 July 2018 nitude of Cr contamination in a Mediterranean region (Assopos-Thiva and Central Evia (Euboea) Basins, Greece); Received in revised form 14 September 2018 (b) combine spatial distribution of Cr in soil and groundwater with land use maps; (c) determine geochemical Accepted 14 September 2018 constraints on contamination by Cr; and (d) provide information that will be useful for better management of Available online 15 September 2018 land use in a Mediterranean type ecosystem in order to prevent further degradation of natural resources. Editor: Mae Mae Sexauer Gustin The spatial diversity of Cr distribution in soils and groundwater throughout the C.