Depictions of Food Critics in Popular Media

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Wsfa Journal Tb , ;,;T He W S F a J 0 U R N a L

THE WSFA JOURNAL TB , ;,;T HE W S F A J 0 U R N A L (The Official Organ of the Washington S. F. Association) Issue Number 76: April-May '71 1971 DISCLAVE SPECIAL n X Copyright \,c) 1971 by Donald-L. Miller. All rights reserved for contributors. The JOURNAL Staff Managing Editor & Publisher — Don Miller, 12315 Judson Rd., Wheaton, MD, USA, 20 906. Associate Editors — Art Editor: Alexis Gilliland, 2126 Penna. Ave., N.W., Washington, DC, 20037. Fiction Editors: Doll St Alexis Gilliland (address above). SOTWJ Editor: OPEN (Acting Editor: Don Miller). Overseas Agents — Australia: Michael O'Brien, 15>8 Liverpool St., Hobart, Tasmania, Australia, 7000 Benelux: Michel Feron, Grand-Place 7, B—I4.28O HANNUT, Belgium. Japan:. Takumi Shibano, I-II4-IO, 0-0kayama, Meguro-ku, Tokyo, Japan. Scandinavia: Per Insulander, Midsommarv.. 33> 126 35 HMgersten, Sweden. South Africa: A.B. Ackerman, POBox 25U5> Pretoria, Transvaal, Rep. of So.Africa. United Kingdom: Peter Singleton, 60W4, Broadmoor Hospital, Block I4, Crowthorne, Berks. RG11 7EG, England. Still needed for France, Germany, Italy, South Timerica, and Soain. Contributing Editors — Bibliographer: Mark Owings. Film Reviewer: Richard Delap. Book Reviewers: Al Gechter, Alexis Music Columnist: Harry Warner, Jr. Gilliland, Dave Halterman, James News Reporters: ALL OPEN (Club, Con R. Newton, Fred Patten, Ted Pauls, vention, Fan, Pro, Publishing). Mike Shoemaker. (More welcome.) Pollster: Mike Shoemaker. Book Review Indexer: Hal Hall. Prozine Reviewers: Richard Delap, Comics Reviewer: Kim Weston. Mike Shoemaker (serials only). Fanzine Reviewers: Doll Gilliland, Pulps: Bob Jones. Mike Shoemaker. Special mention to Jay Kay Klein and Feature Writer: Alexis Gilliland. -

George Harrison

COPYRIGHT 4th Estate An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF www.4thEstate.co.uk This eBook first published in Great Britain by 4th Estate in 2020 Copyright © Craig Brown 2020 Cover design by Jack Smyth Cover image © Michael Ochs Archives/Handout/Getty Images Craig Brown asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins. Source ISBN: 9780008340001 Ebook Edition © April 2020 ISBN: 9780008340025 Version: 2020-03-11 DEDICATION For Frances, Silas, Tallulah and Tom EPIGRAPHS In five-score summers! All new eyes, New minds, new modes, new fools, new wise; New woes to weep, new joys to prize; With nothing left of me and you In that live century’s vivid view Beyond a pinch of dust or two; A century which, if not sublime, Will show, I doubt not, at its prime, A scope above this blinkered time. From ‘1967’, by Thomas Hardy (written in 1867) ‘What a remarkable fifty years they -

U.S. National Tour of the West End Smash Hit Musical To

Tweet it! You will always love this musical! @TheBodyguardUS comes to @KimmelCenter 2/21–26, based on the Oscar-nominated film & starring @Deborah_Cox Press Contacts: Amanda Conte [email protected] (215) 790-5847 Carole Morganti, CJM Public Relations [email protected] (609) 953-0570 U.S. NATIONAL TOUR OF THE WEST END SMASH HIT MUSICAL TO PLAY PHILADELPHIA’S ACADEMY OF MUSIC FEBRUARY 21–26, 2017 STARRING GRAMMY® AWARD NOMINEE AND R&B SUPERSTAR DEBORAH COX FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE (Philadelphia, PA, December 22, 2016) –– The Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts and The Shubert Organization proudly announce the Broadway Philadelphia run of the hit musical The Bodyguard as part of the show’s first U.S. National tour. The Bodyguard will play the Kimmel Center’s Academy of Music from February 21–26, 2017 starring Grammy® Award-nominated and multi-platinum R&B/pop recording artist and film/TV actress Deborah Cox as Rachel Marron. In the role of bodyguard Frank Farmer is television star Judson Mills. “We are thrilled to welcome this new production to Philadelphia, especially for fans of the iconic film and soundtrack,” said Anne Ewers, President & CEO of the Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts. “This award-winning stage adaption and the incomparable Deborah Cox will truly bring this beloved story to life on the Academy of Music stage.” Based on Lawrence Kasdan’s 1992 Oscar-nominated Warner Bros. film, and adapted by Academy Award- winner (Birdman) Alexander Dinelaris, The Bodyguard had its world premiere on December 5, 2012 at London’s Adelphi Theatre. The Bodyguard was nominated for four Laurence Olivier Awards including Best New Musical and Best Set Design and won Best New Musical at the WhatsOnStage Awards. -

89Th Annual Academy Awards® Oscar® Nominations Fact

® 89TH ANNUAL ACADEMY AWARDS ® OSCAR NOMINATIONS FACT SHEET Best Motion Picture of the Year: Arrival (Paramount) - Shawn Levy, Dan Levine, Aaron Ryder and David Linde, producers - This is the first nomination for all four. Fences (Paramount) - Scott Rudin, Denzel Washington and Todd Black, producers - This is the eighth nomination for Scott Rudin, who won for No Country for Old Men (2007). His other Best Picture nominations were for The Hours (2002), The Social Network (2010), True Grit (2010), Extremely Loud & Incredibly Close (2011), Captain Phillips (2013) and The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014). This is the first nomination in this category for both Denzel Washington and Todd Black. Hacksaw Ridge (Summit Entertainment) - Bill Mechanic and David Permut, producers - This is the first nomination for both. Hell or High Water (CBS Films and Lionsgate) - Carla Hacken and Julie Yorn, producers - This is the first nomination for both. Hidden Figures (20th Century Fox) - Donna Gigliotti, Peter Chernin, Jenno Topping, Pharrell Williams and Theodore Melfi, producers - This is the fourth nomination in this category for Donna Gigliotti, who won for Shakespeare in Love (1998). Her other Best Picture nominations were for The Reader (2008) and Silver Linings Playbook (2012). This is the first nomination in this category for Peter Chernin, Jenno Topping, Pharrell Williams and Theodore Melfi. La La Land (Summit Entertainment) - Fred Berger, Jordan Horowitz and Marc Platt, producers - This is the first nomination for both Fred Berger and Jordan Horowitz. This is the second nomination in this category for Marc Platt. He was nominated last year for Bridge of Spies. Lion (The Weinstein Company) - Emile Sherman, Iain Canning and Angie Fielder, producers - This is the second nomination in this category for both Emile Sherman and Iain Canning, who won for The King's Speech (2010). -

Films Winning 4 Or More Awards Without Winning Best Picture

FILMS WINNING 4 OR MORE AWARDS WITHOUT WINNING BEST PICTURE Best Picture winner indicated by brackets Highlighted film titles were not nominated in the Best Picture category [Updated thru 88th Awards (2/16)] 8 AWARDS Cabaret, Allied Artists, 1972. [The Godfather] 7 AWARDS Gravity, Warner Bros., 2013. [12 Years a Slave] 6 AWARDS A Place in the Sun, Paramount, 1951. [An American in Paris] Star Wars, 20th Century-Fox, 1977 (plus 1 Special Achievement Award). [Annie Hall] Mad Max: Fury Road, Warner Bros., 2015 [Spotlight] 5 AWARDS Wilson, 20th Century-Fox, 1944. [Going My Way] The Bad and the Beautiful, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 1952. [The Greatest Show on Earth] The King and I, 20th Century-Fox, 1956. [Around the World in 80 Days] Mary Poppins, Buena Vista Distribution Company, 1964. [My Fair Lady] Doctor Zhivago, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 1965. [The Sound of Music] Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, Warner Bros., 1966. [A Man for All Seasons] Saving Private Ryan, DreamWorks, 1998. [Shakespeare in Love] The Aviator, Miramax, Initial Entertainment Group and Warner Bros., 2004. [Million Dollar Baby] Hugo, Paramount, 2011. [The Artist] 4 AWARDS The Informer, RKO Radio, 1935. [Mutiny on the Bounty] Anthony Adverse, Warner Bros., 1936. [The Great Ziegfeld] The Song of Bernadette, 20th Century-Fox, 1943. [Casablanca] The Heiress, Paramount, 1949. [All the King’s Men] A Streetcar Named Desire, Warner Bros., 1951. [An American in Paris] High Noon, United Artists, 1952. [The Greatest Show on Earth] Sayonara, Warner Bros., 1957. [The Bridge on the River Kwai] Spartacus, Universal-International, 1960. [The Apartment] Cleopatra, 20th Century-Fox, 1963. -

The Magic Flute Programme

Programme Notes September 4th, Market Place Theatre, Armagh September 6th, Strule Arts Centre, Omagh September 10th & 11th, Lyric Theatre, Belfast September 13th, Millennium Forum, Derry-Londonderry 1 Welcome to this evening’s performance Brendan Collins, Richard Shaffrey, Sinéad of The Magic Flute in association with O’Kelly, Sarah Richmond, Laura Murphy Nevill Holt Opera - our first ever Mozart and Lynsey Curtin - as well as an all-Irish production, and one of the most popular chorus. The showcasing and development operas ever written. of local talent is of paramount importance Open to the world since 1830 to us, and we are enormously grateful for The Magic Flute is the first production of the support of the Arts Council of Northern Austins Department Store, our 2014-15 season to be performed Ireland which allows us to continue this The Diamond, in Northern Ireland. As with previous important work. The well-publicised Derry / Londonderry, seasons we have tried to put together financial pressures on arts organisations in Northern Ireland an interesting mix of operas ranging Northern Ireland show no sign of abating BT48 6HR from the 18th century to the 21st, and however, and the importance of individual combining the very well known with the philanthropic support and corporate Tel: +44 (0)28 7126 1817 less frequently performed. Later this year sponsorship has never been greater. I our co-production (with Opera Theatre would encourage everyone who enjoys www.austinsstore.com Company) of Donizetti’s L’Elisir d’Amore seeing regular opera in Northern Ireland will tour the Republic of Ireland, following staged with flair and using the best local its successful tour of Northern Ireland operatic talent to consider supporting us last year. -

Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network

Syracuse University SURFACE Dissertations - ALL SURFACE May 2016 Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network Laura Osur Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/etd Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Osur, Laura, "Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network" (2016). Dissertations - ALL. 448. https://surface.syr.edu/etd/448 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the SURFACE at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations - ALL by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract When Netflix launched in April 1998, Internet video was in its infancy. Eighteen years later, Netflix has developed into the first truly global Internet TV network. Many books have been written about the five broadcast networks – NBC, CBS, ABC, Fox, and the CW – and many about the major cable networks – HBO, CNN, MTV, Nickelodeon, just to name a few – and this is the fitting time to undertake a detailed analysis of how Netflix, as the preeminent Internet TV networks, has come to be. This book, then, combines historical, industrial, and textual analysis to investigate, contextualize, and historicize Netflix's development as an Internet TV network. The book is split into four chapters. The first explores the ways in which Netflix's development during its early years a DVD-by-mail company – 1998-2007, a period I am calling "Netflix as Rental Company" – lay the foundations for the company's future iterations and successes. During this period, Netflix adapted DVD distribution to the Internet, revolutionizing the way viewers receive, watch, and choose content, and built a brand reputation on consumer-centric innovation. -

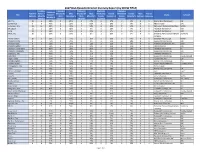

1Q12 IPG Cable Nets.Xlsm

Independent Programming means a telecast on a Comcast or Total Hours of Independent Programming NBCUniversal network that was produced by an entity Aired During the First Quarter 2012 unaffiliated with Comcast and/or NBCUniversal. Each independent program or series listed has been classified as new or continuing. 2061:30:00 Continuing Independent Series and Programming means series (HH:MM:SS) and programming that began prior to January 18, 2011 but ends on or after January 18, 2011. New Independent Series and Programming means series and programming renewed or picked up on or after January 18, 2011 or that were not on the network prior to January 18, INDEPENDENT PROGRAMMING Independent Programming Report Chiller First Quarter 2012 Network Program Name Episode Name Initial (I) or New (N) or Primary (P) or Program Description Air Date Start Time* End Time* Length Repeat (R)? Continuing (C)? Multicast (M)? (MM/DD/YYYY) (HH:MM:SS) (HH:MM:SS) (HH:MM:SS) CHILLER ORIGINAL CHILLER 13: THE DECADE'S SCARIEST MOVIE MOMENTS R C P Reality: Other 01/01/2012 01:00:00 02:30:00 01:30:00 CHILLER ORIGINAL CHILLER 13: HORROR’S CREEPIEST KIDS R C P Reality: Other 01/01/2012 02:30:00 04:00:00 01:30:00 CHILLER ORIGINAL CHILLER 13: THE DECADE'S SCARIEST MOVIE MOMENTS R C P Reality: Other 01/01/2012 08:00:00 09:30:00 01:30:00 CHILLER ORIGINAL CHILLER 13: HORROR’S CREEPIEST KIDS R C P Reality: Other 01/01/2012 09:30:00 11:00:00 01:30:00 CHILLER ORIGINAL CHILLER 13: THE DECADE'S SCARIEST MOVIE MOMENTS R C P Reality: Other 01/01/2012 11:00:00 12:30:00 01:30:00 CHILLER -

Emmy Nominations

69th Emmy Awards Nominations Announcements July 13, 2017 (A complete list of nominations, supplemental facts and figures may be found at Emmys.com) Emmy Noms to date Previous Wins to Category Nominee Program Network 69th Emmy Noms Total (across all date (across all categories) categories) LEAD ACTRESS IN A DRAMA SERIES Viola Davis How To Get Away With Murder ABC 1 3 1 Claire Foy The Crown Netflix 1 1 NA Elisabeth Moss The Handmaid's Tale Hulu 1 8 0 Keri Russell The Americans FX Networks 1 2 0 Evan Rachel Wood Westworld HBO 1 2 0 Robin Wright House Of Cards Netflix 1 6 0 LEAD ACTOR IN A DRAMA SERIES Sterling K. Brown This Is Us NBC 1 2 1 Anthony Hopkins Westworld HBO 1 5 2 Bob Odenkirk Better Call Saul AMC 1 11 2 Matthew Rhys The Americans FX Networks 2* 3 0 Liev Schreiber Ray Donovan Showtime 3* 6 0 Kevin Spacey House Of Cards Netflix 1 11 0 Milo Ventimiglia This Is Us NBC 1 1 NA * NOTE: Matthew Rhys is also nominated for Guest Actor In A Comedy Series for Girls * NOTE: Liev Schreiber also nominamted twice as Narrator for Muhammad Ali: Only One and Uconn: The March To Madness LEAD ACTRESS IN A LIMITED SERIES OR A MOVIE Carrie Coon Fargo FX Networks 1 1 NA Felicity Huffman American Crime ABC 1 5 1 Nicole Kidman Big Little Lies HBO 1 2 0 Jessica Lange FEUD: Bette And Joan FX Networks 1 8 3 Susan Sarandon FEUD: Bette And Joan FX Networks 1 5 0 Reese Witherspoon Big Little Lies HBO 1 1 NA LEAD ACTOR IN A LIMITED SERIES OR A MOVIE Riz Ahmed The Night Of HBO 2* 2 NA Benedict Cumberbatch Sherlock: The Lying Detective (Masterpiece) PBS 1 5 1 -

Perth Amboy Tt

c s'O. 21 SOUTH AMBOY, N. J., SATURDAY, AUGUST 29, 1914. Price Three Cents. WILL TRY TO GET P. V. DeGRAW DIES $1 A YEAR SALARY THE BANNER AGAIN LOVELY NAMED AT WASHINGTON EOR CUSTODIAN Joel Parker Council No. 69, Jr. O. After an illness of six months, When the reports of committees U. A. M., is planning on sending an- Peter Vorhees DeGraw, former Fourth FOR MAYOR Assistant Postmaster General, died MAKE SUITE were reached in the regular order o-f" other large delegation to the next business at the regular meeting of. Past Councilors Association meeting, early last Saturday morning at hi tho Board of Education Thursday •which Is to held In Milltown on Tues- Democrats Decide to Endorse Him— home, 210 Maryland avenue northeast, Enfarse Mayor Dey and Councilman- Washington D. C. His wife and son evening a report was in order from day, Sept. 8th. At a meeting of this C. W. Stuart Will Run for Coun- at-Large Stratton for Re-Election the finance committee on the hill sub- kind held in Jamesburg some time were at the bedside at the time of his mitted by the present city treasurer- ago this council won a banner for cilman-at-Large—R. M. Mack for death. Mr. DeGraw had been sinking —Dr. Albright Named for Council- for three hundred and eighty dollars having the largest delegation present. for two weeks. A hemorrhage ear- City Clerk—Committeemen File man in Second Ward and fred Isely for his services as custodian of A short time later, at the last meet- ly In tho evening of Friday wa school moneys for the past two years. -

The Meal Times Newsletter of Meals on Wheels Central Texas

THE MEAL TIMES NEWSLETTER OF MEALS ON WHEELS CENTRAL TEXAS Volume 42, Issue 5 December 2017 “I am so Thankful for Meals on Wheels” “I’m a jack of all trades,” says Mary who lives by the big oak of living,” she explains with a 84-year-old Linda Richards, tree?’ I’m not exaggerating,” Ms. shake of her head. before quickly adding, “and Richards recalls with a laugh. master of none.” Major health issues, including a broken hip, also forced a Ask the Santa Fe, New Mexico different kind of living on her. native about the jobs she held Physically unable to work, and as a younger woman, and homebound and alone in her East she’ll list occupations long Austin apartment, she relies on since replaced by automation – Meals on Wheels Central Texas telephone operator - and those to nourish her body and spirit. that, decades later, still require She appreciates the nutritious a living, breathing human being food our volunteers deliver to her - card shill for a Las Vegas casino door. “That takes care of lunch (more on that Vegas vocation in and that’s a big deal. That’s kind a bit). MOWCTX client Linda Richards of the main meal,” she says. in her East Austin apartment Ms. Richards began her working But as much as she loves the life with Southwestern Bell in Other jobs included stints as healthy food, she treasures the the 1950’s, back when folks a manicurist, an assistant to a daily visits from the folks who needed operators to place podiatrist, a home-health care bring her lunch, and credits them long distance calls or look up aide, and that aforementioned with vastly improving her outlook telephone numbers. -

Report by Show Title

2017 DGA Episodic Director Diversity Report (by SHOW TITLE) Combined # Episodes # Episodes # Episodes # Episodes Combined TotAl # of FemAle + Directed by Male Directed by Male Directed by FemAle Directed by FemAle Male FemAle Title FemAle + Studio Network Episodes Minority Male CaucasiAn % Male Minority % FemAle CaucasiAn % FemAle Minority % Unknown Unknown Minority % Episodes CaucasiAn Minority CaucasiAn Minority 100, The 12 4 33% 8 67% 2 17% 2 17% 0 0% 0 0 Warner Bros Companies CW 12 Monkeys 8 6 75% 2 25% 5 63% 1 13% 0 0% 0 0 NBC Universal Syfy 13 Reasons Why 13 11 85% 2 15% 7 54% 2 15% 2 15% 0 0 Paramount Pictures Corporation Netflix 24: Legacy 11 2 18% 9 82% 0 0% 2 18% 0 0% 0 0 Twentieth Century Fox FOX A.P.B. 11 4 36% 7 64% 2 18% 1 9% 1 9% 0 0 Twentieth Century Fox FOX Affair, The 10 1 10% 9 90% 0 0% 1 10% 0 0% 0 0 Showtime Pictures Development Showtime Company Altered Carbon 10 3 30% 7 70% 1 10% 2 20% 0 0% 0 0 Skydance Pictures, LLC Netflix American Crime 8 6 75% 2 25% 0 0% 2 25% 4 50% 0 0 Disney/ABC Companies ABC American Gods 9 2 22% 7 78% 1 11% 1 11% 0 0% 0 0 Fremantle Productions, Inc. Starz! American Gothic 13 7 54% 6 46% 3 23% 2 15% 2 15% 0 0 CBS Companies CBS American Horror Story 10 8 80% 2 20% 2 20% 5 50% 1 10% 0 0 Twentieth Century Fox FX American Housewife 22 8 36% 13 59% 2 9% 5 23% 1 5% 1 0 Disney/ABC Companies ABC Americans, The 13 6 46% 7 54% 2 15% 3 23% 1 8% 0 0 Twentieth Century Fox FX Andi Mack 13 3 23% 10 77% 2 15% 0 0% 0 0% 0 1 Disney/ABC Companies Disney Channel Angie Tribeca 10 3 30% 7 70% 1 10% 1 10% 1 10% 0 0 Turner Films, Inc.