Edward Weston

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brett Weston June 2020

#51 June 2020 Cameraderie Brett Weston (1911-1993) Brett Weston and his father, Edward Weston I started this series on great photographers in October 2012 with Edward Weston, the photographer with whom I was then, and now, most impressed. Now, for the beginning of the second set of 50 articles—an anniversary of sorts—I am turning to his son, Brett Weston. Please have a look at his Wikipedia article here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brett_Weston From the Wikipedia article: [Brett] Weston began taking photographs in 1925, …. He began showing his photographs with Edward Weston in 1927, was featured at the international exhibition at Film und Foto in Germany at age 17, and mounted his first one-man museum retrospective at age 21 at the De Young Museum in San Francisco in January, 1932. Brett Weston was credited by photography historian Beaumont Newhall as the first photographer to make negative space the subject of a photograph. I am impressed by the younger Weston’s extraordinary versatility in his photography, possibly more so than his father—a difficult decision for me. In the sample images below, I am trying to show that versatility. Street Corner, New York 1944 I am charmed by these two extremely formal compositions. Nude in Pool [1979-1982] Dunes Weston apparently saw similarities between nudes and dunes, and exhibited them together. This is Weston’s famous broken glass image, said by one critic to be the first photograph ever to capture “negative space.” Edward Weston by Brett Weston Manuel Hernández Galván by Edward Weston, 1924 Do you have any doubt that Brett Weston shot this image of his father in the style of his father’s famous shot of General Galván? . -

Transforming Practices

Transforming Practices: Imogen Cunningham’s Botanical Studies of the 1920s Caroline Marsh Spring Semester 2014 Dr. Juliet Bellow, Art History University Honors in Art History Imogen Cunningham worked for decades as a professional photographer, creating predominantly portraits and botanical studies. In 1932, she joined the influential Group f.64, a group of West Coast photographers who worked to pioneer the concept of “Straight Photography,” a movement that emphasized the use of sharp focus and high contrast. Members of Group f.64 included Ansel Adams and Edward Weston, whose works have since overshadowed other photographers in the group. Cunningham has been marginalized in histories of Group f.64, and in the history of photography in general, despite evidence of her development of many important photographic practices during her lifetime. This paper builds on scholarship about Group f.64, using biographical information and analysis of her photographs, to argue that Cunningham influenced more of the ideas in the group than has been recognized, especially in her focus on the simplification of form and the creation of compelling compositions. Focusing on her botanical studies, I show that many of the ideas of f.64 existed in her oeuvre before the formal creation of the group. Analysis of her participation in the group reveals her contribution to developments in art photography in that period, and shows that her gender played a key role in historical accounts that downplay her significant contributions to f.64. Marsh 2 Imogen Cunningham became well known in her lifetime as an independent and energetic photographer from the West Coast, whose personality defined her more than the photographs she created or her contribution to the developing straight photography movement in California. -

Post-Visualization Jerry N. Uelsmann 1967

Post-Visualization Edward Weston, in his efforts to find a language suitable and indigenous to his own life and time, developed a method of working which today we refer to as pre-visualization. Jerry N. Uelsmann 1967 Weston, in his daybooks, writes, the finished print is pre-visioned complete in every detail of texture, movement, proportion, before exposure-the shutter’s release automatically and finally fixes my conception, allowing no after manipulation. It is Weston the master craftsman, not Weston the visionary, that performs the darkroom ritual. The distinctively different documentary’ approach exemplified by the work of Walker Evans and thedecisive moment approach of Henri Cartier Bresson have in common with Weston’s approach their emphasis on the discipline of seeing and their acceptance of a prescribed darkroom ritual. These established, perhaps classic traditions are now an important part of the photographic heritage that we all share. For the moment let us consider experimentation in photography. Although I do not pretend to be a historian, it appears to me that there have been three major waves of open experimentation in photography; the first following the public announcement of the Daguerreotype process in 1839; the second right after the turn of the century under the general guidance of Alfred Stieglitz and the loosely knit Photo-Secession group; and the third in the late twenties and thirties under the influence of Moholy-Nagy and the Bauhaus. In each instance there was an initial outburst of enthusiasm, excitement and aliveness. The medium was viewed as something new and fresh possibilities were explored and unanticipated directions were taken. -

Finding Aid for the Dody Weston Thompson Collection, Undated, Circa 1940-1991 AG 258

Center for Creative Photography The University of Arizona 1030 N. Olive Rd. P.O. Box 210103 Tucson, AZ 85721 Phone: 520-621-6273 Fax: 520-621-9444 Email: [email protected] URL: http://creativephotography.org Finding aid for the Dody Weston Thompson Collection, undated, circa 1940-1991 AG 258 Finding aid created by Leslie Squyres, August 2016 AG 258: Dody Thompson Weston - page 2 Dody Weston Thompson Collection, circa 1940-1991 AG 258 Creator Dody Weston Thompson Quantity/ Extent 6 linear feet Language of Materials English Biographical/ Historical Note Photographer Dody Weston Thompson, (1923-2012), was a founder of the photographic journal, Aperture and was married and a creative collaborator with the photographer Brett Weston from 1952-1956. Thompson favored creating sharp-focus, realistic photographs of natural objects in the style popularized by Ansel Adams and Edward Weston, both of whom she assisted. In 1952, Thompson was the second photographer to win the San Francisco Museum of Art’s Albert M. Bender Award. Ms. Thompson’s husband of 48 years, aerospace executive Daniel Michael Thompson died in 2008. Dody Weston Thompson died in Los Angeles on October 14, 2012, at the age of 89. Scope and Content Note Photographs and contact prints by Dody Thompson Weston, undated, circa 1940-1991; one photograph by John Sexton and one photograph by Jerome Baker. Arrangement Chronological Restrictions Conditions Governing Access Access to this collection requires an appointment with the Volkerding Study Center. Conditions Governing Use It is the responsibility of the user to obtain permission from the copyright owner (which could be the institution, the creator of the record, the author or his/her transferees, heirs, legates or literary executors) prior to any copyright-protected uses of the collection. -

Edward Weston Periodical Collection: Finding Aid

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8154ng6 No online items Edward Weston periodical collection: Finding Aid Finding aid prepared by Diann Benti. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens Rare Books Department 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2191 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org © 2015 The Huntington Library. All rights reserved. Edward Weston periodical 645289 1 collection: Finding Aid Overview of the Collection Title: Edward Weston periodical collection Dates (inclusive): 1930-1980 Bulk dates: 1950-1980 Collection Number: 645289 Creator: Waltman, Jack, collector.Waltman, Beverly, collector. Extent: 55 items in 3 boxes. Repository: The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Rare Books Department 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2191 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org Abstract: This collection contains fifty-five magazines, exhibition catalogs, brochures, and other printed material related to the career and life of Edward Weston (1886-1958), a pioneering 20th-century American photographer known for his exploration of form in landscapes, still lifes, and nudes. The collection includes published writings by and about Weston; publications containing his photographs; exhibition catalogs and brochures that feature his work and his contemporaries; as well as later tributes and articles about the photographer. Language: English. Access Open to qualified researchers by prior application through the Reader Services Department. For more information, contact Reader Services. Publication Rights The Huntington Library does not require that researchers request permission to quote from or publish images of this material, nor does it charge fees for such activities. -

![The Photographs of Edward Weston [By] Nancy Newhall](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1770/the-photographs-of-edward-weston-by-nancy-newhall-2611770.webp)

The Photographs of Edward Weston [By] Nancy Newhall

The photographs of Edward Weston [by] Nancy Newhall Author Weston, Edward, 1886-1958 Date 1946 Publisher The Museum of Modern Art Exhibition URL www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/2374 The Museum of Modern Art's exhibition history— from our founding in 1929 to the present—is available online. It includes exhibition catalogues, primary documents, installation views, and an index of participating artists. MoMA © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art " __ - LIBRAHY THE MUSEUSVf OF MODERN ART Received: ! MCHW£ EDWARD WESTON THE PHOTOGRAPHSOF PORTRAIT OF EDWARD WESTON BY ANSEL ADAMS, 1945 EDWARD WESTON NANCY NEWH THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish especially to thank Edward Weston for the many months of work and the understanding collabora tion, maintained across a continent, which he has contributed to every stage of this book and the exhibition it accompanies. To Beaumont Newhall, for his invaluable aid in preparing the text and the bibliography, to Charis Wilson Weston, to whose writings and suggestions I am much indebted, and to Jean Chariot for permission to quote from his manuscript, I am particularly grateful. I wish also to thank Mrs. Gladys C. Bolt, Mrs. Gladys Bronson Hart, Mrs. Rae Davis Knight, Mrs. Mary Weston Seaman and Mrs. Flora Chandler Weston for lending the chloride, platinum, and palladio prints which represent Weston's earliest work. Nancy Newhall TRUSTEESOF THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART Stephen C. Clark, Chairman of the Board; Henry Allen Moe, 1st Vice-Chairman; Sam A. Lewisohn, 2nd Vice- chairman; John Hay Whitney, President; Nelson A. Rockefeller, 1st Vice-President; John E. Abbott, Executive Vice-President; Ranald H. -

The Photography of Edward Weston

Edward Weston, American Photographer 1886-1958 Julia E. Benson ARTS 1611 (Drawing II) Spring Semester, 2001 Edward Henry Weston, widely regarded as one of the premier photographers of the twentieth century, was born on March 24, 1886, in Highland Park, IL, a suburb of Chicago. Weston’s father was a physician; his mother died while Weston was very young, so that he was primarily raised by his older sister. An indifferent student at best, Weston drifted through school until he was sixteen, when a belated birthday gift of a Kodak Bulls-Eye No. 2 box camera from his father changed his life. Photography immediately enthralled him, though he soon realized the limitations of his initial equipment and saved his money for a better camera, a 5x7-inch ground glass model with a tripod. He set up a darkroom and began spending as much time possible photographing the world around him. Almost none of Weston’s early work survives, though in the surviving work Weston’s eye for composition is evident. Lake Michigan, Chicago (1904) and Spring, Washington Park, Chicago (1903) both show a structure and organization that lifts this obviously amateur work out of the realm of the ordinary. In 1906, Weston moved to California after a visit to his sister May in Tropico (now Glendale). He began to make his living first as a surveyor, then as an itinerant photographer, which suited him well. However, that position offered an uncertain living, and he recognized the need for further study in photography. Thus, in 1909 he briefly returned to the Chicago area for the only formal art training of his life: he attended the Illinois College of Photography to develop the skills and methodology that would carry his artistic vision forward. -

Elist 47: Recent Aquisitionsphotography 1 Elist 47: Recent Aquisitions ART CAHAN LITERATURE BOOKSELLER, LTD AMERICANA

ANDREW Elist 47: Recent AquisitionsPHOTOGRAPHY 1 Elist 47: Recent Aquisitions ART CAHAN LITERATURE BOOKSELLER, LTD AMERICANA Terms: All items are offered subject to prior sale. A phone call, email or fax insures availability. Shipping and insurance charges are additional. Returns are accepted for any reason within ten days of receipt; we request notification in advance. All items must be returned in the exact condition in which they were received. Library and Institutional billing requirements will be accommodated. Customers new to us are requested to send payment in advance or provide references. For your convenience we also accept payment by Visa, MasterCard, American Express, and PayPal. Ohio customers will be charged the applicable sale tax. Overseas customers please note: all items will be shipped via insured priority airmail unless otherwise requested. A statement will be sent under separate cover and we request payment in full upon receipt. We accept payment by bank transfer, a check drawn upon a U.S. bank in dollars, or via credit card. This list represents just a small portion of our stock. If there are specific items you are seeking, we would be pleased to receive your desiderata. We hope you will keep in mind that we are always pleased to consider fine individual items or entire collections for purchase. To receive our future E-Lists and other notifications, please send us your email address so we can let you know when a new list is available at our website, cahanbooks.com. PO Box 5403 • Akron, OH 44334 • 330.252.0100 Tel/Fax [email protected] • www.cahanbooks.com 1. -

Edward Weston's Studio Nudes and Still

INTERDEPENDENT PARTS OF THE WHOLE: EDWARD WESTON‘S STUDIO NUDES AND STILL LIFES, 1925-1933 By LAURA CHRISTINE BARTON A THESIS Presented to the Department of Art History And the Honors College of the University of Oregon In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Bachelor of Arts May 2011 2 Copyright 2011 by Laura Barton 3 An Abstract of the Thesis of Laura Christine Barton for the degree of Bachelor of Arts In the department of Art History May 17, 2011 Title: INTERDEPENDENT PARTS OF THE WHOLE: EDWARD WESTON‘S STUDIO NUDES AND STILL LIFES, 1925-1933 Approved: _________________________________________ Professor Kate Mondloch Photographer Edward Weston has long been hailed as one of the heroes of modern photography and has been praised for his stunning approach to landscapes, nudes, and still-lifes. This thesis examines his treatment of the nude female form and examines the relationship that the photographs establish between the human body and the natural world. Through a series of in-depth visual and formal analyses of his early nudes and still-lifes, I show that Weston un-animated the human body, while animating the vegetables, shells, and landscapes that he photographed. Thus, he created not a vertical hierarchy where humans are placed above the natural world, but instead created a horizontal plane where all natural forms are equalized. This approach differs from most of the pre-existing scholarship on Weston, which has long interpreted his work using either the biographical method or feminist theory, both of which serve primarily to either maintain or reject Weston‘s heroic status; this paper attempts to instead explain how the photographs themselves serve to create meaning. -

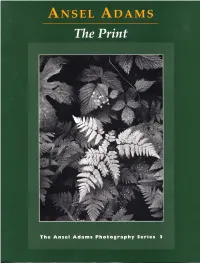

The Print Ansel Adams

The Print The Ansel Adams Photography Series I Book 3 The Print Ansel Adams with the collaboration of Robert Baker UTILE, BROWN AND COMPANY NEW YORK BOSTON In 1976, Ansel Adam elected Little, Brown and Company a the sole au thorized publisher of his book, calendars, and posters. At the same time, he established The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust in ord er to ensu re the continuity and quality of hi legacy - both arti tic and environmental. As Ansel Adams himself wrote, "Perhaps the most important characteri tic of my work is what may be called print quality. It is very important that the reproduc ti ons be as good as you can pos ibly get them." The autho rized book, calendars, and posters published by Little, Brown have been rigorously supervised by the Trust to make certain that Adams' exacting standards of quality are maintained. Only uch work published by Little, Brown and Company can be considered authentic representations of the genius of Ansel Adams. Frontispiece: Northern Cascade·, Washington (hazy sunlight) , 1960 Copyright © 1980, 2003 by the Trustees of The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust All rights reserved in all countries. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including informati on storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publi her, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review. Little, Brown and Company 1271 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020 Vi it our Web site at www.bulfinchpress.com This is the third volume of The Ansel Adams Photography SeTies. -

From Pictorialism to Modernism the Salon Photographs of Florence Kemmler and Roland Schneider

For Immediate Release: From Pictorialism to Modernism The Salon Photographs of Florence Kemmler and Roland Schneider Joseph Bellows Gallery is pleased to present rare vintage photographs by California Pictorialists Roland Schneider and Florence Kemmler. Photographic Pictorialism was an international aesthetic movement, a philosophy, and a style, developed toward the end of the 19th century. The introduction of the dry-plate process in the late 1870s, and the Kodak camera in 1888, made taking photographs relatively easy, and photography became widely practiced. Pictorialist photographers set themselves apart from the ranks of new hobbyist photographers by demonstrating that photography was capable of far more than a literal description of a subject. Through Pictorialist organizations, publications, and exhibitions, photography became recognized as an art form. The idea of the print as a carefully hand-crafted, unique object equal to a painting gained acceptance. The husband-and-wife team of Roland E. Schneider (1884-1934), and Florence B. Kemmler (1900-1972), were internationally exhibited salon photographers whose beautifully rendered works straddle both Pictorialist and modernist sensibilities. The San Diego couple worked together using the same 3¼ x 4¼ Graflex cameras and identical printing and mounting techniques. Nearly all their photographs were contact printed on warm, brownish black-toned chlorobromide papers. Their work was recognized by the jurors of both the prestigious Pictorial Photographers of America, founded in 1916 by Clarence H. White, and the Camera Pictorialists of Los Angeles, whose annual international salon was hosted by the Los Angeles County Museum between 1918 and 1945. So respected was this particular event that it drew as many as 2,000 entries worldwide, with only about 200 chosen for inclusion in the exhibition. -

INFORMATION to USERS the Most Advanced Technology Has Been Used to Photo Graph and Reproduce This Manuscript from the Microfilm Master

The significance of the photographic message Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Fuller, David, 1960- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 04/10/2021 03:33:26 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/277233 INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book.