Glimpses of Adivasi Situation in Gudalur, the Nilgiris

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Particulars of Some Temples of Kerala Contents Particulars of Some

Particulars of some temples of Kerala Contents Particulars of some temples of Kerala .............................................. 1 Introduction ............................................................................................... 9 Temples of Kerala ................................................................................. 10 Temples of Kerala- an over view .................................................... 16 1. Achan Koil Dharma Sastha ...................................................... 23 2. Alathiyur Perumthiri(Hanuman) koil ................................. 24 3. Randu Moorthi temple of Alathur......................................... 27 4. Ambalappuzha Krishnan temple ........................................... 28 5. Amedha Saptha Mathruka Temple ....................................... 31 6. Ananteswar temple of Manjeswar ........................................ 35 7. Anchumana temple , Padivattam, Edapalli....................... 36 8. Aranmula Parthasarathy Temple ......................................... 38 9. Arathil Bhagawathi temple ..................................................... 41 10. Arpuda Narayana temple, Thirukodithaanam ................. 45 11. Aryankavu Dharma Sastha ...................................................... 47 12. Athingal Bhairavi temple ......................................................... 48 13. Attukkal BHagawathy Kshethram, Trivandrum ............. 50 14. Ayilur Akhileswaran (Shiva) and Sri Krishna temples ........................................................................................................... -

Post Offices

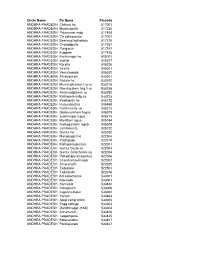

Circle Name Po Name Pincode ANDHRA PRADESH Chittoor ho 517001 ANDHRA PRADESH Madanapalle 517325 ANDHRA PRADESH Palamaner mdg 517408 ANDHRA PRADESH Ctr collectorate 517002 ANDHRA PRADESH Beerangi kothakota 517370 ANDHRA PRADESH Chowdepalle 517257 ANDHRA PRADESH Punganur 517247 ANDHRA PRADESH Kuppam 517425 ANDHRA PRADESH Karimnagar ho 505001 ANDHRA PRADESH Jagtial 505327 ANDHRA PRADESH Koratla 505326 ANDHRA PRADESH Sirsilla 505301 ANDHRA PRADESH Vemulawada 505302 ANDHRA PRADESH Amalapuram 533201 ANDHRA PRADESH Razole ho 533242 ANDHRA PRADESH Mummidivaram lsg so 533216 ANDHRA PRADESH Ravulapalem hsg ii so 533238 ANDHRA PRADESH Antarvedipalem so 533252 ANDHRA PRADESH Kothapeta mdg so 533223 ANDHRA PRADESH Peddapalli ho 505172 ANDHRA PRADESH Huzurabad ho 505468 ANDHRA PRADESH Fertilizercity so 505210 ANDHRA PRADESH Godavarikhani hsgso 505209 ANDHRA PRADESH Jyothinagar lsgso 505215 ANDHRA PRADESH Manthani lsgso 505184 ANDHRA PRADESH Ramagundam lsgso 505208 ANDHRA PRADESH Jammikunta 505122 ANDHRA PRADESH Guntur ho 522002 ANDHRA PRADESH Mangalagiri ho 522503 ANDHRA PRADESH Prathipadu 522019 ANDHRA PRADESH Kothapeta(guntur) 522001 ANDHRA PRADESH Guntur bazar so 522003 ANDHRA PRADESH Guntur collectorate so 522004 ANDHRA PRADESH Pattabhipuram(guntur) 522006 ANDHRA PRADESH Chandramoulinagar 522007 ANDHRA PRADESH Amaravathi 522020 ANDHRA PRADESH Tadepalle 522501 ANDHRA PRADESH Tadikonda 522236 ANDHRA PRADESH Kd-collectorate 533001 ANDHRA PRADESH Kakinada 533001 ANDHRA PRADESH Samalkot 533440 ANDHRA PRADESH Indrapalem 533006 ANDHRA PRADESH Jagannaickpur -

District Survey Report of Madurai District

Content 1.0 Preamble ................................................................................................................. 1 2.0 Introduction .............................................................................................................. 1 2.1 Location ............................................................................................................ 2 3.0 Overview of Mining Activity In The District .............................................................. 3 4.0 List of Mining Leases details ................................................................................... 5 5.0 Details of the Royalty or Revenue received in last Three Years ............................ 36 6.0 Details of Production of Sand or Bajri Or Minor Minerals In Last Three Years ..... 36 7.0 Process of deposition of Sediments In The River of The District ........................... 36 8.0 General Profile of Maduari District ....................................................................... 27 8.1 History ............................................................................................................. 28 8.2 Geography ....................................................................................................... 28 8.3 Taluk ................................................................................................................ 28 8.2 Blocks .............................................................................................................. 29 9.0 Land Utilization Pattern In The -

Nilgiris District, Tamil Nadu Connie Smith Tamil Nadu Overview

Nilgiris District, Tamil Nadu Connie Smith Tamil Nadu Overview Tamil Nadu is bordered by Pondicherry, Kerala, Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh. Sri Lanka, which has a significant Tamil minority, lies off the southeast coast. Tamil Nadu, with its traceable history of continuous human habitation since pre-historic times has cultural traditions amongst the oldest in the world. Colonised by the East India Company, Tamil Nadu was eventually incorporated into the Madras Presidency. After the independence of India, the state of Tamil Nadu was created in 1969 based on linguistic boundaries. The politics of Tamil Nadu has been dominated by DMK and AIADMK, which are the products of the Dravidian movement that demanded concessions for the 'Dravidian' population of Tamil Nadu. Lying on a low plain along the southeastern coast of the Indian peninsula, Tamil Nadu is bounded by the Eastern Ghats in the north and Nilgiri, Anai Malai hills and Palakkad (Palghat Gap) on the west. The state has large fertile areas along the Coromandel coast, the Palk strait, and the Gulf of Mannar. The fertile plains of Tamil Nadu are fed by rivers such as Kaveri, Palar and Vaigai and by the northeast monsoon. Traditionally an agricultural state, Tamil Nadu is a leading producer of agricultural products. Tribal Population As per 2001 census, out of the total state population of 62,405,679, the population of Scheduled Castes is 11,857,504 and that of Scheduled Tribes is 651,321. This constitutes 19% and 1.04% of the total population respectively.1 Further, the literacy level of the Adi Dravidar is only 63.19% and that of Tribal is 41.53%. -

Details of First Responders – 2018 – 2019 Vellore District

DETAILS OF FIRST RESPONDERS – 2018 – 2019 VELLORE DISTRICT NAME OF THE TALUK : VELLORE. Sl. Name of the Name of the Revenue Name of the First Mobile No. No Vulnerable Area Village Responders 1) Muthusami 9514954416 2) Gunasekaran 7871615967 1. Edaiyansathu Pennathur 3) Ganesan 9600934430 4) Tamilselvam 8220767805 5) T. Ganesan 9367754175 1) Kannadasan 9445745734 2) Kesavan 9442530657 2. Nelvoy Nelvoy 3) Sathishkumar 9543965703 4) Chezhiyan 9952585195 5) Lakshmi 9629789644 1) Neelamegam 9443658724 S/O Munisamy 3. Kilvallam AD Colony Kilvalam 2) Jeevagan 9444857429 S/O Subiramani 1) Tamilselvan 9940793955 4. Kilpallipattu Kilpallipattu 2) Saravanan 9715552976 3) Raja 9367642067 1) M. Rajini Kanth 9597626548 2) Prabhu 9500342299 5. Kaniyambadi AD Kaniyambadi 3) Manimaran 9786792887 Colony 4).Philomina 0416- 2265353 5).Jayaraj Singh 938311725 1) Ravikumar 9994440815 2 ) Chakkaravarthy 9195987115 3) Anbhazagan 9486722281 4) Sivaji 9994614140 6. Kansalpet North Vellore 5) Venkatraman 9444521997 6) S. Palani @ 9944860722 Beedipalani 7) Manimaran 9345302659 8) Nirmala Britto 0416-2220886 1) Ravikumar 9994440815 Indira Nagar, 2) Manoharan 8619288073 7. Puliyanthoppe, South Vellore Rangasamy Nagar, 3 )Sankar 9629511708 Vasanthapuram 4).Chakkaravarthi 9195987115 1) Durai Arasan 9487048269 Sambath Nagar 2) Mohan 9788458739 8. (Navaneetham Koil South Vellore 3) Krishnamayan 9444244474 street) 4) Subramani 9994648001 1) K. Murugan 9994616031 2) V. Ramesh 9994616127 3) K. Madhan 8056387884 4) C. Anbu 9789190868 5) E. Karthick 9894732129 9. Thidir Nagar Shenpakkam 6) Mohammed 8124545924 7) Manikandan 9597133267 8) Ajith 8056727418 9) Baskaran 9952579270 10) Balu S/o Velu 9042004177 NAME OF THE TALUK : ANAICUT Sl. Name of the Name of the Revenue Name of the First Mobile No. No Vulnerable Area Village Responders 1. -

Socio-Economic Characteristics of Tribal Communities That Call Themselves Hindu

Socio-economic Characteristics of Tribal Communities That Call Themselves Hindu Vinay Kumar Srivastava Religious and Development Research Programme Working Paper Series Indian Institute of Dalit Studies New Delhi 2010 Foreword Development has for long been viewed as an attractive and inevitable way forward by most countries of the Third World. As it was initially theorised, development and modernisation were multifaceted processes that were to help the “underdeveloped” economies to take-off and eventually become like “developed” nations of the West. Processes like industrialisation, urbanisation and secularisation were to inevitably go together if economic growth had to happen and the “traditional” societies to get out of their communitarian consciousness, which presumably helped in sustaining the vicious circles of poverty and deprivation. Tradition and traditional belief systems, emanating from past history or religious ideologies, were invariably “irrational” and thus needed to be changed or privatised. Developed democratic regimes were founded on the idea of a rational individual citizen and a secular public sphere. Such evolutionist theories of social change have slowly lost their appeal. It is now widely recognised that religion and cultural traditions do not simply disappear from public life. They are also not merely sources of conservation and stability. At times they could also become forces of disruption and change. The symbolic resources of religion, for example, are available not only to those in power, but also to the weak, who sometimes deploy them in their struggles for a secure and dignified life, which in turn could subvert the traditional or establish structures of authority. Communitarian identities could be a source of security and sustenance for individuals. -

The Dravidian Languages

THE DRAVIDIAN LANGUAGES BHADRIRAJU KRISHNAMURTI The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 2RU, UK 40 West 20th Street, New York, NY 10011–4211, USA 477 Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, VIC 3207, Australia Ruiz de Alarc´on 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain Dock House, The Waterfront, Cape Town 8001, South Africa http://www.cambridge.org C Bhadriraju Krishnamurti 2003 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2003 Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeface Times New Roman 9/13 pt System LATEX2ε [TB] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 0521 77111 0hardback CONTENTS List of illustrations page xi List of tables xii Preface xv Acknowledgements xviii Note on transliteration and symbols xx List of abbreviations xxiii 1 Introduction 1.1 The name Dravidian 1 1.2 Dravidians: prehistory and culture 2 1.3 The Dravidian languages as a family 16 1.4 Names of languages, geographical distribution and demographic details 19 1.5 Typological features of the Dravidian languages 27 1.6 Dravidian studies, past and present 30 1.7 Dravidian and Indo-Aryan 35 1.8 Affinity between Dravidian and languages outside India 43 2 Phonology: descriptive 2.1 Introduction 48 2.2 Vowels 49 2.3 Consonants 52 2.4 Suprasegmental features 58 2.5 Sandhi or morphophonemics 60 Appendix. Phonemic inventories of individual languages 61 3 The writing systems of the major literary languages 3.1 Origins 78 3.2 Telugu–Kannada. -

(IQAC) and Submission of Annual Quality Assurance Report (AQAR) in Accredited

Guidelines for the Creation of the Internal Quality Assurance Cell (IQAC) and Submission of Annual Quality Assurance Report (AQAR) in Accredited Institutions (Revised in October 2013) NATIONAL ASSESSMENT AND ACCREDITATION COUNCIL An Autonomous Institution of the University Grants Commission P. O. Box. No. 1075, Opp: NLSIU, Nagarbhavi, Bangalore - 560 072 India NAAC VISION To make quality the defining element of higher education in India through a combination of self and external quality evaluation, promotion and sustenance initiatives. MISSION To arrange for periodic assessment and accreditation of institutions of higher education or units thereof, or specific academic programmes or projects; To stimulate the academic environment for promotion of quality of teaching-learning and research in higher education institutions; To encourage self-evaluation, accountability, autonomy and innovations in higher education; To undertake quality-related research studies, consultancy and training programmes, and To collaborate with other stakeholders of higher education for quality evaluation, promotion and sustenance. Value Framework To promote the following core values among the HEIs of the country: Contributing to National Development Fostering Global Competencies among Students Inculcating a Value System among Students Promoting the Use of Technology Quest for Excellence Sl Page No: Contents Nos. 1 Introduction 4 2 Objective 4 3 Strategies 4 4 Functions 5 5 Benefits 5 6 Composition of the IQAC 5 7 The role of coordinator 6 8 Operational -

Coimbatore Commissionerate Jurisdiction

Coimbatore Commissionerate Jurisdiction The jurisdiction of Coimbatore Commissionerate will cover the areas covering the entire Districts of Coimbatore, Nilgiris and the District of Tirupur excluding Dharapuram, Kangeyam taluks and Uthukkuli Firka and Kunnathur Firka of Avinashi Taluk * in the State of Tamil Nadu. *(Uthukkuli Firka and Kunnathur Firka are now known as Uthukkuli Taluk). Location | 617, A.T.D. STR.EE[, RACE COURSE, COIMBATORE: 641018 Divisions under the jurisdiction of Coimbatore Commissionerate Sl.No. Divisions L. Coimbatore I Division 2. Coimbatore II Division 3. Coimbatore III Division 4. Coimbatore IV Division 5. Pollachi Division 6. Tirupur Division 7. Coonoor Division Page 47 of 83 1. Coimbatore I Division of Coimbatore Commissionerate: Location L44L, ELGI Building, Trichy Road, COIMBATORT- 641018 AreascoveringWardNos.l to4,LO to 15, 18to24and76 to79of Coimbatore City Municipal Corporation limit and Jurisdiction Perianaickanpalayam Firka, Chinna Thadagam, 24-Yeerapandi, Pannimadai, Somayampalayam, Goundenpalayam and Nanjundapuram villages of Thudiyalur Firka of Coimbatore North Taluk and Vellamadai of Sarkar Samakulam Firka of Coimbatore North Taluk of Coimbatore District . Name of the Location Jurisdiction Range Areas covering Ward Nos. 10 to 15, 20 to 24, 76 to 79 of Coimbatore Municipal CBE Corporation; revenue villages of I-A Goundenpalayam of Thudiyalur Firka of Coimbatore North Taluk of Coimbatore 5th Floor, AP Arcade, District. Singapore PIaza,333 Areas covering Ward Nos. 1 to 4 , 18 Cross Cut Road, Coimbatore Municipal Coimbatore -641012. and 19 of Corporation; revenue villages of 24- CBE Veerapandi, Somayampalayam, I-B Pannimadai, Nanjundapuram, Chinna Thadagam of Thudiyalur Firka of Coimbatore North Taluk of Coimbatore District. Areas covering revenue villages of Narasimhanaickenpalayam, CBE Kurudampalayam of r-c Periyanaickenpalayam Firka of Coimbatore North Taluk of Coimbatore District. -

Women's Participation and MGNREGP with Special Reference to Coonoor in Nilgiris District: Issues and Challenges

Munich Personal RePEc Archive Women’s Participation and MGNREGP with Special Reference to Coonoor in Nilgiris District: Issues and Challenges C, Dr. Jeeva Providence College for Women, Coonoor, Tamilnadu, India December 2017 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/107315/ MPRA Paper No. 107315, posted 02 Jun 2021 14:12 UTC WOMEN’S PARTICIPATION AND MGNREGP WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO COONOOR IN NILGIRIS DISTRICT: ISSUES AND CHALLENGES Mrs. C.JEEVA. MA, M.Phil.NET Assistant Professor, Department of Economics, Providence College for Women, Coonoor, Tamilnadu, India Email. [email protected], contact No. 9489524836 ABSTRACT: The MGNREGA 2005, plays a significant role to meet the practical as well as strategic needs of women’s participation. It is a self –targeting programme, intended in increasing outreach to the poor and marginalized sections of the society such as women and helping them towards the cause of financial and economic inclusion in the society. In the rural milieu, it promises employment opportunities for women and their empowerment. While their hardships have been reduced due to developmental projects carried out in rural areas, self-earnings have improved their status to a certain extent. However, women’s decision for participation and their share in MNREGP jobs is hindered by various factors. Apart from some structural problems, inattentiveness and improper implementation of scheme, social attitudes, exploitation and corruption have put question marks over the intents of the programme. At this juncture, the litmus test of the policy will have an impact on the entire process of rural development and women employment opportunities in India. There is excitement as well as disappointment over the implementation on the Act. -

Tamil Nadu Government Gazette

© [Regd. No. TN/CCN/467/2012-14. GOVERNMENT OF TAMIL NADU [R. Dis. No. 197/2009. 2013 [Price: Rs. 27.20 Paise. TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY No. 10] CHENNAI, WEDNESDAY, MARCH 13, 2013 Maasi 29, Nandhana, Thiruvalluvar Aandu–2044 Part VI—Section 4 Advertisements by private individuals and private institutions CONTENTS PRIVATE ADVERTISEMENTS Pages Change of Names .. 553-619 Notice .. 620 NOTICE NO LEGAL RESPONSIBILITY IS ACCEPTED FOR THE PUBLICATION OF ADVERTISEMENTS REGARDING CHANGE OF NAME IN THE TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE. PERSONS NOTIFYING THE CHANGES WILL REMAIN SOLELY RESPONSIBLE FOR THE LEGAL CONSEQUENCES AND ALSO FOR ANY OTHER MISREPRESENTATION, ETC. (By Order) Director of Stationery and Printing. CHANGE OF NAMES 8416. I, Barakathu Nisha, wife of Thiru Syed Ahamed 8419. My son, P. Jayakodi, born on 10th October 2010 Kabeer, born on 1st April 1966 (native district: (native district: Virudhunagar), residing at Old No. 8-23, New Ramanathapuram), residing at Old No. 4-66, New No. 4/192, No. 8-99, West Street, Veeranapuram, Kalingapatti, Chittarkottai Post, Ramanathapuram-623 513, shall henceforth Sankarankoil Taluk, Tirunelveli-627 753, shall henceforth be be known as BARAKATH NEESHA. known as V.P. RAJA. BARAKATHU NISHA. M. PERUMALSAMY. Ramanathapuram, 4th March 2013. Tirunelveli, 4th March 2013. (Father.) 8420. I, Sarika Kantilal Rathod, wife of Thiru Shripal, born 8417. I, S Rasia Begam, wife of Thiru M. Sulthan, born on on 3rd February 1977 (native district: Chennai), residing at 2nd June 1973 (native district: Dindigul), residing at Old No. 140-13, Periyasamy Road, R.S. Puram Post, Coimbatore- No. 4/115-E, New No. -

Market Feasibility Study for Jackfruit Value Added Products

Research Project on MARKET FEASIBILITY STUDY FOR JACKFRUIT VALUE ADDED PRODUCTS by Dr. Ramesh Mittal Director-National Institute of Agricultural Marketing Dr .K. Sankaran Director-Justice K.S.Hegde Institute of Management Dr. A.P. Achar Dean- Corporate Programmes JKSHIM, Nitte Commissioned by JUSTICE K.S.HEGDE INSTITUTE OF MANAGEMENT and NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF AGRICULTURAL MARKETING, JAIPUR Index Chapter Content Page # I Introduction 3-4 Jackfruit & Value-Added Products: Introduction & II 5-15 Overview III Manufacturing & Distribution 16-23 IV Domestic & International Markets 24-34 V Quality Standards 25-36 VI Technology Support 37-43 VII Development Initiatives – some illustrations 44-47 • Mission Jackfruit’ – Improving the Eco-system for Cultivation and Value-addition: • National Institute for Jackfruit Development VIII 48-69 • Next Steps: An Integrated Approach to Development of Jackfruit Farming Community VIIII • Conclusion 70-71 Annexures I Market study Plan – Jack Fruit products 72-77 II Nutrition and health benefits of jackfruit 78-80 III Process Flow for some Jackfruit Value Added Products 81-86 IV Verities of Jackfruit in India and their characteristics 87 V Jackfruit cultivars/varieties in different countries 88-89 Report and Market Research on Jackfruit Introduction 1.1About Jackfruit The jackfruit is native to parts of South and Southeast Asia and is believed to have originated in the rainforests of Western Ghats of India and is cultivated throughout the lowlands in South and Southeast Asia. Major jackfruit producing countries are Bangladesh, India, Myanmar, Nepal, Thailand, Vietnam, China, Philippines, Indonesia, Malaysia and Sri Lanka. Jackfruit is also found in East Africa as well as throughout Brazil and Caribbean nations such as Jamaica.