March 2019 No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IWGIA ANNUAL REPORT 2018 1 Acknowledgements

ANNUAL REPORT 2018 IWGIA ANNUAL REPORT 2018 1 Acknowledgements IWGIA promotes, protects and defends indigenous peoples’ rights. We promote the recognition, respect and implementation of indigenous peoples’ rights to land, cultural integrity and development on their own terms. We would like to acknowledge all the valuable individuals and groups who have made our work in 2018 possible through various ways of support. We thank: our partners for their continued commitment and integral support; our network for their invaluable resources, time and energy; international institutions and mechanisms for their support and creating a platform for change; academics and experts for their knowledge and insights; our volunteers for their dedication and time; The Indigenous World authors, who year-after-year voluntarily contribute their expertise into this one-of-a-kind documentation tool; our members for their financial and operational support; our individual donors for their generous donations; and our project and institutional donors listed below for their partnership and financial support. DESIGN WWW.NICKPURSERDESIGN.COM COVER PHOTO THE WAYUU PEOPLE/DELPHINE BLAST Contents Indigenous peoples’ rights are key to a sustainable and just world 4 Who we are 6 Our work in 2018 7 Land rights and territorial governance 8 Maasai women elect leaders to their community-based organisation in northern Tanzania 9 Government official promises no village eviction over wildlife project in India 10 Wampis Nation legitimacy strengthened with international and national -

(2016-2017) (Sixteenth Lok Sabha) Ministry of Minority Affairs

39 STANDING COMMITTEE ON SOCIAL JUSTICE AND EMPOWERMENT (2016-2017) (SIXTEENTH LOK SABHA) MINISTRY OF MINORITY AFFAIRS DEMANDS FOR GRANTS (2017-2018) THIRTY-NINTH REPORT LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI March, 2017/Phalguna, 1938 (Saka) i THIRTY-NINTH REPORT STANDING COMMITTEE ON SOCIAL JUSTICE AND EMPOWERMENT (2016-2017) (SIXTEENTH LOK SABHA) MINISTRY OF MINORITY AFFAIRS DEMANDS FOR GRANTS (2017-2018) Presented to Lok Sabha on 17.03.2017 Laid in Rajya Sabha on 17.03.2017 LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI March, 2017/Phalguna, 1938 (Saka) ii CONTENTS PAGE(s) COMPOSITION OF THE COMMITTEE (2016-17) (iv) INTRODUCTION (vi) REPORT CHAPTER - I INTRODUCTORY 1 CHAPTER - II GENERAL PERFORMANCE OF MINISTRY 4 CHAPTER - III FREE COACHING AND ALLIED SCHEME 26 CHAPTER - IV RESEARCH STUDIES MONITORING & 33 EVALUATION OF DEVELOPMENT SCHEME FOR MINORITIES CHAPTER - V SKILL DEVELOPMENT INITIATIVE 36 (SEEKHO AUR KAMAO SCHEME) CHAPTER - VI HAJ DIVISION 50 ANNEXURES I. MINUTES OF THE ELEVENTH SITTING OF 82 THE STANDING COMMITTEE ON SOCIAL JUSTICE AND EMPOWERMENT (2016-17) HELD ON TUESDAY, 28th FEBRUARY, 2017. II. MINUTES OF THE TWELFTH SITTING OF THE 85 STANDING COMMITTEE ON SOCIAL JUSTICE AND EMPOWERMENT (2016-17) HELD ON THURSDAY, 16th MARCH, 2017. APPENDIX STATEMENT OF OBSERVATIONS/ 87 RECOMMENDATIONS iii COMPOSITION OF THE STANDING COMMITTEE ON SOCIAL JUSTICE AND EMPOWERMENT (2016-2017) SHRI RAMESH BAIS - CHAIRPERSON MEMBERS LOK SABHA 2. Shri Kantilal Bhuria 3. Shri Santokh Singh Chaudhary 4. Shri Sher Singh Ghubaya 5. Shri Jhina Hikaka 6. Shri Sadashiv Kisan Lokhande 7. Smt. K. Maragatham 8. Shri Kariya Munda 9. Prof. Seetaram Azmeera Naik 10. Shri Asaduddin Owaisi 11. -

Department of Media and Film Studies Annual Report 2019-2020

Department of Media and Film Studies Annual Report 2019-2020 - 1 - Introduction The Media Studies department at Ashoka University is led by journalists, commentators, researchers, academics and investigative reporters who have wide experience in teaching, reporting, writing and broadcasting. The academic team led by Professor Vaiju Naravane, teaches approximately 25 audio- visual and writing elective courses in a given academic year in the Undergraduate Programme. These range from news writing, audio-visual production, social media, media metrics, film appreciation and cinema, digital storytelling to specialized courses in research methodology, political coverage and business journalism. In a spirit of interdisciplinarity, these courses are cross-listed with other departments like Computer Science, Creative Writing, Political Science or Sociology. The Media Studies department also collaborates with the Centre for Social and Behaviour Change to produce meaningful communication messaging to further development goals. The academic year 2019/2020 was rich in terms of the variety and breadth of courses offered and an enrolment of 130 students from UG to ASP and MLS. Several YIF students also audited our courses. Besides academics, the department also held colloquia on various aspects of the media that explored subjects like disinformation and fake news, hate speech, changing business models in the media, cybersecurity and media law, rural journalism, journalism and the environment, or how the media covers rape and sexual harassment. Faculty published widely, were invited speakers at conferences and events and also won recognition and awards. The department organized field trips that allowed students to hone their journalistic and film-making skills in real life situations. Several graduating students found employment in notable mainstream media organisations and production hubs whilst others pursued postgraduate studies at prestigious international universities. -

THURSDAY, the 14TH MARCH, 2002 (The Rajya Sabha Met in the Parliament House at 11-00 A.M.) 11-00 A.M

THURSDAY, THE 14TH MARCH, 2002 (The Rajya Sabha met in the Parliament House at 11-00 a.m.) 11-00 a.m. 1. Starred Questions The following Starred Questions were orally answered:- Starred Question No. 161 regarding Territorial demarcation between India and Bangladesh. Starred Question No. 162 regarding Export of Basmati rice. Starred Question No. 164 regarding Procurement of paddy at MSP. Answers to remaining Starred Question Nos. 163, 165 to 180 were laid on the Table. 2. Unstarred Questions Answers to Unstarred Question Nos.1164 to 1318 were laid on the Table. 12 Noon 3. Papers Laid on the Table Shri Pramod Mahajan (Minister of Parliamentary Affairs, Minister of Communications and Information Technology) laid on the Table the following papers:— I. A copy (in English and Hindi) of the Ministry of Communications & Information Technology (Department of Information Technology) Notification G.S.R. No. 892 (E) dated 11th December, 2001 publishing the Semiconductor Integrated Circuits Layout Design Rules, 2001, under sub-section (2)(i) of Section 96 of the Semiconductor Circuits Layout Design Act, 2000, II. A copy (in English and Hindi) of the Ministry of Communications & Information Technology (Department of Information Technology) Notification G.S.R. No. 512 (E) dated 9th July, 2001 publishing the Information Technology (Certifying Authority) Regulations, 2001, under sub-section (3) of Section 89 of the Information Technology Act, 2000. Shri Kariya Munda (Minister of Agro and Rural Industries) laid on the Table the following papers:- 14TH MARCH, 2002 (1) A copy each (in English and Hindi) of the following papers, under sub- section (1) of section 19 of the Coir Industries Act, 1953:— (a) Forty-seventh Annual Report of the Coir Board, Kochi, for the year 2000- 2001, together with the Auditor's Report on the Accounts. -

S P Law Review 2017

R AW EV L I . E P W . S.P.Law Review, March-2017 Issue-VS ISSN.NO.2276-7815 A- LAW SECTION 1) Legal education in the era of globalisation – Vision ahead - Dr. Anjali Hastak & Dr. I.J. Rao Page No.1 to 03 2) Global climate change: A warning call for nations - Dr. Snehal S. Fadnavis Page No. 04 to 07 3) Cyberspace and its regulation -Mr. Sachin Matte & Dr. A.U. Shaikh Page No. 08 to 18 4) Fair pricing and fair dealing in Copyright Laws in India - Dr.Archana Sukey Page No. 19 to 23 5) Right to health- A global perspective - Dr. Pankaj Kakde Page No. 24 to 29 6) Judicial appointments : Whose prerogative ? -Dr. Archana Gadekar Page No. 30 to 37 7) Law governing extradition: An Insight - Ravindra S. Kale & Dr. A.U. Shaikh Page No.38 to41 8) Consumer rights against Call Drops - Deepti Khubalkar Page No.42 to 45 9) Hurdles in effective implementations of protection of women from Domestic Violence Act , 2005 - Dr. Abhay Butle Page No.46 to 48 10) India towards cashless society and Its legal implications on Cyberspace - Dr. Manoj Bendle Page No.49 to 53 11) The relevance of constitutional guarantee of Right Against Exploitation with reference to recent incidences of bonded labour in India - Miss. Sneha Sheshrao Kulkarni Page No. 54 to 59 12) Human Rights of disabled persons in the light of “ JEEJA GHOSH’s Case”- A bird’s eye view. - Dr.Shahista Inamdar Page No. 60 to 64 13) Local Governance –Rural and urban development in India - Adv. -

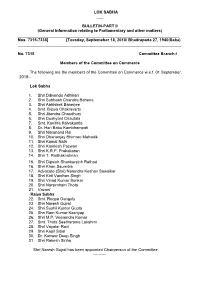

LOK SABHA ___ BULLETIN-PART II (General Information Relating To

LOK SABHA ___ BULLETIN-PART II (General Information relating to Parliamentary and other matters) ________________________________________________________________________ Nos. 7315-7338] [Tuesday, Septemeber 18, 2018/ Bhadrapada 27, 1940(Saka) _________________________________________________________________________ No. 7315 Committee Branch-I Members of the Committee on Commerce The following are the members of the Committee on Commerce w.e.f. 01 September, 2018:- Lok Sabha 1. Shri Dibyendu Adhikari 2. Shri Subhash Chandra Baheria 3. Shri Abhishek Banerjee 4. Smt. Bijoya Chakravarty 5. Shri Jitendra Chaudhury 6. Shri Dushyant Chautala 7. Smt. Kavitha Kalvakuntla 8. Dr. Hari Babu Kambhampati 9. Shri Nityanand Rai 10. Shri Dhananjay Bhimrao Mahadik 11. Shri Kamal Nath 12. Shri Kamlesh Paswan 13. Shri K.R.P. Prabakaran 14. Shri T. Radhakrishnan 15. Shri Dipsinh Shankarsinh Rathod 16. Shri Khan Saumitra 17. Advocate (Shri) Narendra Keshav Sawaikar 18. Shri Kirti Vardhan Singh 19. Shri Vinod Kumar Sonkar 20. Shri Narsimham Thota 21. Vacant Rajya Sabha 22. Smt. Roopa Ganguly 23. Shri Naresh Gujral 24. Shri Sushil Kumar Gupta 25. Shri Ram Kumar Kashyap 26. Shri M.P. Veerendra Kumar 27. Smt. Thota Seetharama Lakshmi 28. Shri Vayalar Ravi 29. Shri Kapil Sibal 30. Dr. Kanwar Deep Singh 31. Shri Rakesh Sinha Shri Naresh Gujral has been appointed Chairperson of the Committee. ---------- No.7316 Committee Branch-I Members of the Committee on Home Affairs The following are the members of the Committee on Home Affairs w.e.f. 01 September, 2018:- Lok Sabha 1. Dr. Sanjeev Kumar Balyan 2. Shri Prem Singh Chandumajra 3. Shri Adhir Ranjan Chowdhury 4. Dr. (Smt.) Kakoli Ghosh Dastidar 5. Shri Ramen Deka 6. -

MISSION SARANDA a War for India's Natural Resources Gladson Dungdung Deshaj Prakashan, Bihar-Jharkhand June 2015

MISSION SARANDA A War for India's Natural Resources Gladson Dungdung Deshaj Prakashan, Bihar-Jharkhand June 2015 As I write this review, Joe Lamb, who set up The Borneo Project, emails me from Kota Kinabulu, Malaysia about the success of the World Indigenous Summit on Environment and Rivers [WISER], that he attended last week. Indigenous peoples around the world, it seems, are showing their mettle ever more forcefully. More and more non-tribal people are taking notice of their plight and beginning to appreciate what the human species as a whole is losing. Governments and supra- national corporations are being forced to act. For example, in the same week as WISER, Tata Steel's Tribal Cultural Society held their second “Pan-India Tribal Conclave”. The Gandhi Foundation's initiative in opening negotiations with Tata Steel in 2013 about their human rights abuses was very likely a factor in their decision to hold the first one last year. With no apparent irony in their publicity, the date for that Conclave was chosen, they said, “to mark the birth anniversary of tribal freedom fighter Birsa Munda”. Birsa Munda was a freedom fighter and is honoured to this day by all Adivasis as a hero. He was born on 15 November 1875 at Ulihatu, Ranchi District, in what was then Bihar. He was arrested on 3 March 1900 in Jamkopai forest while he was sleeping along with his tribal guerrilla army which was fighting against British forces. About 460 tribal people were arrested of which one was given capital punishment, 39 were transported for life and 23 given 14 years jail sentences. -

“The Government Wants Us to Shut Up” January 29, 2014 10:11 Amviews: 39

CHINA “The government wants us to shut up” January 29, 2014 10:11 amViews: 39 There is rising discontent among Indonesian migrant workers in Hong Kong after the Erwiana scandal Sally Tang, Socialist Action (CWI in Hong Kong) “I have two kids and two parents to feed. I must send money home to them; if I don’t feed them, who will? I must carry on.” Nisa, in Hong Kong since 2008, explained why hundreds of thousands of Indonesian women come to Hong Kong, Singapore and other cities to work as domestic workers. Nisa’s first job was not a good experience. She suffered verbal and sometimes physical abuse from her employer. The reason she decided to endure this nightmare and finish her two-year contract is because of the excessive agency fees. “I had to finish my contract even if I’m abused by my boss. If I change job, the agency will charge me again, a new fee, which takes up another seven months of my salary.” http://chinaworker.info/en/2014/01/29/5697/ “Free Wu Guijun” – protests in 13 cities around the world Support grows in campaign for release of imprisoned workers’ representative chinaworker.info and CWI reporters It is now five months since Wu Guijun, a migrant worker employed at the Diweixin Product Factory in Shenzhen, was taken into detention by police. Wu had been elected by his workmates during a month-long strike against […] http://chinaworker.info/en/2013/10/26/4819/ INDIA Candle vigil and protest in solidarity of death of Arunachal Student in Delhi 03 Feb TCN News, 2 Feb 2014, New Delhi: Civil society groups such as Khudai Khidmatgar, NAPM, Asha Parivar and SSSC (Save Sharmila Solidarity Campaign) organised a protest gathering in support of North Eastern people near Rajghat. -

Download File

©️ Indigenous Peoples Rights International, 2021. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the publisher's prior written permission. The quotation, reproduction without alteration, and transmission of this document are authorized, provided that it is for non-commercial purposes and with attribution to the copyright holder. Indigenous Peoples Rights International. “Defending Our Lands, Territories and Natural Resources Amid the COVIDt-19 Pandemic: Annual Report on Criminalization of, Violence and Impunity Against Indigenous Peoples.” April 2021. Baguio City, Philippines. Photos Cover Page (Top) Young Lumad women protesting in UP Diliman with placards saying "Women, our place is in the struggle." (Photo: Save Our Schools (SOS) Network) (Bottom) The Nahua People of the ejido of Carrizalillo blocked the entrance to the mines on September 3, 2020 due to Equinox Gold’s breach of the agreement. (Photo: Centro de Derechos Humanos de la Montaña Tlachinollan) Indigenous Peoples Rights International # 7 Planta baja, Calvary St., Easter Hills Subdivision Central Guisad, Baguio City 2600 Filipinas www.iprights.org ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The country contexts and case stories were developed with support from: Diel Mochire, Joseph Itongwa and Aquilas Koko Ngomo (Democratic Republic of Congo); Sonia Guajajara and Carolina Santana (Brazil); Leonor Zalabata, Francisco Vanegas, Maria Elvira Guerra and Héctor Jaime Vinasco (Colombia); Sandra Alarcon, Ariane Assemat, Carmen Herrera and Abel Barrera (Mexico); Gladson Dungdung, Rajendra Tadavi, Siraj Dutta, Sidhart Nayak and Praful Samantaray (India); Prince Albert Turtogo, Tyrone Beyer, Jill Cariño, Marifel Macalanda, and Giya Clemente (Philippines). -

Annual Report 2012-13

Annual Report 2012-13 Social Initiatives for Growth and Networking (SIGN), Ranchi “Social Initiatives for Growth and Networking” (SIGN) is the official Body of the Catholic Bishops of Jharkhand for social concern and human development. It anchors the effort of the 8 Social Service Societies of the dioceses of Ranchi, Gumla, Jamshedpur, Simdega, Khunti, Daltoganj, Hazaribag and Dumka in promoting a just and humane Society based on the Gospel values of love, peace, equality and dignity to all. Mission An Empowered society - Vision Well Knit and Disciplined, that upholds Human dignity of the oppressed and the A just and humane society marginalized, especially the Tribals and based on the Gospel values of the Dalits by means of advocacy, liaison love, peace, equality and Networking with the diocesan and dignity to all. institutions in collaboration with Government and like-minded organizations. GOAL Ensuring sustainable livelihood opportunities to all, especially the poor and the marginalized by promoting effective governance, enabling a holistic and healthy society, imparting quality education, recognizing women’s contribution to society and fostering inter-religious harmony. Thrust Natural Resource Management, Agriculture, Animation and Empowerment, Good Governance, Gender, Tribal Development, Health, Education and Inter-Religious Harmony Area Jharkhand & Andamans are immediate focus area for operation 2 Governing Body S.N Name Address Designation 1 His Eminence Cardinal Archbishop’s House, Dr. Camil Bulcke Path, P.B. No-05, Ranchi-834001, Ex-Officio Telesphore P. Toppo Jharkhand 2 Most Rev. Felix Toppo S.J Bishop’s House, P.O. Golmuri, Jamshedpur – 831003, Jharkhand President 3 Most Rev. Binay Kandulna Bishop House, P.O. -

March Monthly Magazine Engli

IMPORTANT DAYS IN FEBRUARY February 02 World Wetlands Day February 04 World Cancer Day Interim Budget - 2019 2 February 10 National De-worming Day National News 5 February 12 National Productivity Day International News 12 500+ G.K. One Liner Questions 18 February 13 World Radio Day Awards 38 February 14 Valentine Day New Appointments 42 February 20 World Day of Social Justice Sports 47 February 28 National Science Day Banking & Financial Awareness 52 IMPORTANT DAYS IN MARCH Defence & Technology 55 Study Notes 58 March 01 World Civil Defence Day Tricky Questions 69 March 03 World Wildlife Day SSC CGL (Tier-I) Practice Test Paper 80 March 04 National Security Day RRB JE (PRE) Practice Test Paper 92 March 08 International Womens Day SSC GD (Tier-I) Practice Test Paper 102 March 13 No Smoking Day IMPORTANT RATES March 22 World Day for Water March 24 World TB Day (03-02-2019) March 27 World Theatre Day Repo Rate 6.50% Reverse Repo Rate 6.25% Marginal Standing Facility Rate 6.75% Statutory Liquidity Ratio 19.25% Cash Reserve Ratio 4% Bank Rate 6.75% RRB (JE) : 11th & 14th February 19 SSC CGL: 11th& 21th February 19 For Admission Contact : IBT Nearest Center or Call Toll Free www.makemyexam.in & www.ibtindia.com performance through the mock tests taken by the Institute every week and the online mock tests provided by the Institute. Thus they will get to know about their strong and weak areas which act as a key strength while taking the examination. IBT: What according to you is the best strategy while taking any competitive exam? Rahul: Sir, for any examination, selection of proper Name: Rahul Bhatia questions is very important. -

As Others See Us

as others see us... BIRSA SINCE 1987 BIRSA SINCE 1987 we are, we were, we will be here! we are, we were, we will be here! we are, we were, we will be here! Contents 5 As Others See Us 7 Prof. Kamal Kabra 9 Mr. Gladson Dungdung 11 Prof. Arvind Rajagopal 13 Dr. Alf Gunvald Nilsen 15 Dr. Ghanshyam Singh 17 Mr. Johannes Lapping 19 Mr. Roger Moody We are grateful to Noel Aranha, Toronto, Canada, for the booklet design and to Panos South Asia for the use of their picture, all gratis; to a fellow Indian in the USA for meeting the printing cost of this booklet. Cover and inside photo by Johann Rousselot, Paris, France. Back cover photo by Tirth Raj Birulee, BIRSA. E as others see us... e the Adivasis1/Dalits of this our Greater Jharkhand homeland (encompassing the Adivasi Wregions of Chhattisgarh, Orissa and West Bengal) trace our history from our ancestors, whose resistance to all forms of colonialism spans 200 years. Today, in their footsteps, we continue the fight to protect our identity, culture, and economy. Our identity and survival depends on our ability to protect our land, forest and other natural resources. In order to sustain these struggles, our movement needed a space for reflection, documentation and training. In 1986 a group of activists and intellectuals set rolling the process of developing an institution to fulfil this need. They founded Bindrai Institute for Research Study & Action BIRSA- and in 1987-88 it received its registration under the Societies Registration Act. From an abandoned shed in Amlatola, Chaibasa, BIRSA today has grown into four branches as shown in the diagram on the next page.