TABLE of CONTENTS Page

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DISTRICT BASELINE: Nakasongola, Nakaseke and Nebbi in Uganda

EASE – CA PROJECT PARTNERS EAST AFRICAN CIVIL SOCIETY FOR SUSTAINABLE ENERGY & CLIMATE ACTION (EASE – CA) PROJECT DISTRICT BASELINE: Nakasongola, Nakaseke and Nebbi in Uganda SEPTEMBER 2019 Prepared by: Joint Energy and Environment Projects (JEEP) P. O. Box 4264 Kampala, (Uganda). Supported by Tel: +256 414 578316 / 0772468662 Email: [email protected] JEEP EASE CA PROJECT 1 Website: www.jeepfolkecenter.org East African Civil Society for Sustainable Energy and Climate Action (EASE-CA) Project ALEF Table of Contents ACRONYMS ......................................................................................................................................... 4 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT .................................................................................................................... 5 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................. 6 CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................. 8 1.1 Background of JEEP ............................................................................................................ 8 1.2 Energy situation in Uganda .................................................................................................. 8 1.3 Objectives of the baseline study ......................................................................................... 11 1.4 Report Structure ................................................................................................................ -

STATEMENT by H.E. Yoweri Kaguta Museveni President of the Republic

STATEMENT by H.E. Yoweri Kaguta Museveni President of the Republic of Uganda At The Annual Budget Conference - Financial Year 2016/17 For Ministers, Ministers of State, Head of Public Agencies and Representatives of Local Governments November11, 2015 - UICC Serena 1 H.E. Vice President Edward Ssekandi, Prime Minister, Rt. Hon. Ruhakana Rugunda, I was informed that there is a Budgeting Conference going on in Kampala. My campaign schedule does not permit me to attend that conference. I will, instead, put my views on paper regarding the next cycle of budgeting. As you know, I always emphasize prioritization in budgeting. Since 2006, when the Statistics House Conference by the Cabinet and the NRM Caucus agreed on prioritization, you have seen the impact. Using the Uganda Government money, since 2006, we have either partially or wholly funded the reconstruction, rehabilitation of the following roads: Matugga-Semuto-Kapeeka (41kms); Gayaza-Zirobwe (30km); Kabale-Kisoro-Bunagana/Kyanika (101 km); Fort Portal- Bundibugyo-Lamia (103km); Busega-Mityana (57km); Kampala –Kalerwe (1.5km); Kalerwe-Gayaza (13km); Bugiri- Malaba/Busia (82km); Kampala-Masaka-Mbarara (416km); Mbarara-Ntungamo-Katuna (124km); Gulu-Atiak (74km); Hoima-Kaiso-Tonya (92km); Jinja-Mukono (52km); Jinja- Kamuli (58km); Kawempe-Kafu (166km); Mbarara-Kikagati- Murongo Bridge (74km); Nyakahita-Kazo-Ibanda-Kamwenge (143km); Tororo-Mbale-Soroti (152km); Vurra-Arua-Koboko- Oraba (92km). 2 We are also, either planning or are in the process of constructing, re-constructing or rehabilitating -

Nakaseke Constituency: 109 Nakaseke South County

Printed on: Monday, January 18, 2021 16:36:23 PM PRESIDENTIAL ELECTIONS, (Presidential Elections Act, 2005, Section 48) RESULTS TALLY SHEET DISTRICT: 069 NAKASEKE CONSTITUENCY: 109 NAKASEKE SOUTH COUNTY Parish Station Reg. AMURIAT KABULETA KALEMBE KATUMBA KYAGULA MAO MAYAMBA MUGISHA MWESIGYE TUMUKUN YOWERI Valid Invalid Total Voters OBOI KIIZA NANCY JOHN NYI NORBERT LA WILLY MUNTU FRED DE HENRY MUSEVENI Votes Votes Votes PATRICK JOSEPH LINDA SSENTAMU GREGG KAKURUG TIBUHABU ROBERT U RWA KAGUTA Sub-county: 001 KAASANGOMBE 014 BUKUUKU 01 TIMUNA/KAFENE 716 1 0 1 0 278 2 0 1 0 1 140 424 43 467 0.24% 0.00% 0.24% 0.00% 65.57% 0.47% 0.00% 0.24% 0.00% 0.24% 33.02% 9.21% 65.22% 02 LUKYAMU PR. SCHOOL 778 2 2 0 1 348 2 2 0 1 0 110 468 24 492 0.43% 0.43% 0.00% 0.21% 74.36% 0.43% 0.43% 0.00% 0.21% 0.00% 23.50% 4.88% 63.24% 03 BUKUUKU PRI. SCHOOL 529 0 0 1 1 188 0 1 0 0 0 74 265 3 268 0.00% 0.00% 0.38% 0.38% 70.94% 0.00% 0.38% 0.00% 0.00% 0.00% 27.92% 1.12% 50.66% Parish Total 2023 3 2 2 2 814 4 3 1 1 1 324 1157 70 1227 0.26% 0.17% 0.17% 0.17% 70.35% 0.35% 0.26% 0.09% 0.09% 0.09% 28.00% 5.70% 60.65% 015 BULYAKE 01 NJAGALABWAMI COMM. -

Nakaseke Makes Model Town Plan

40 The New Vision, FrIday, June 4, 2010 NAKASEKE DISTRICT REVIEW SUPPLEMENT Farmers benefit from Caritas support JOHN KASOZI By John Kasozi education, in August 1993 increased, I got married truck. Next year, he plans he moved to Kampala to the following year.” to buy a plot in Kampala ILSON Nsobya find employment. He initial- Nsobya now has 15 and build a commercial could not ly wanted to work as a acres of land under structure in future. believe, when vehicle mechanic, but he pineapples. He pays school fees Wa lady she met ended up as a cleaner. He notes that on for his four children and six in the bank paid sh24,000 “I decided to go back average an acre of others. as school fees for her home after working for one pineapple brings in about Joyce Kizito, the kindergarten child. That and half years,” says sh5m per year. But with Kamukamu community was in 1993 when his Nsobya. intensive farming, a farmer resource person from monthly pay was One morning in 1994, can garner about sh10m, Kawula, Luweero who sh20,000. Nsobya decided to pack his he says. is also a CARITAS “From that day, I became four-inch mattress, The cost of one pineapple beneficiary says before restless. I wondered how Panasonic radio, a basin ranges between sh600 to they started getting I would pay fees for my and utensils. He used his sh1, 000, Nsobya says support from from the children, rent, feed the savings of sh3,000 for adding that his clientele is organisation in 2002, their family, settle medical transport. -

ACCESS 2018 ANNUAL REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY EXECUTIVE SUMMARY EXECUTIVE Executive Summary

ACCESS 2018 ANNUAL REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY EXECUTIVE SUMMARY EXECUTIVE Executive Summary 2 3 he African Community Centre for With additional support from our Working with international partners, Social Sustainability (ACCESS) is partners, we have been able to ACCESS has been able to set up T a community-based organisation graduate 24 preschool children and income generating projects, and in the rural district of Uganda called maintained the number of preschool established three patient-centered care Nakaseke. It was founded on the children at 62. We have provided clinics for non-Communicable diseases premise that everyone has a right to scholastic materials for 320 OVCs (NCD) serving over 400 patients. Our a healthy life. Our mission is to work in primary and secondary schools. model has been presented to Uganda with vulnerable people in resource- We held our first graduation for the Ministry of Health and has been limited settings through provision of nurses and midwives in our school, adopted by several partners in the NCD medical care, education and economic 98% passed their national exam with field in Uganda. empowerment to create long lasting excellence, and most of them are change that is owned by the entire employed. We have been able to maintain our community. connection with the community Our medical care services have greatly through training and empowering 122 For the year 2018, we focused on improved. In this year, we treated community health workers who provide strengthening the activities of ACCESS over 3,196 patients and provided support to all our projects. We have in the areas of support for orphans family planning services to 29,614 welcomed new partners and have and other vulnerable children (OVCs), clients including 8,884 youths aged worked on new areas of need based on nursing and midwifery education, 15-24 years in and out of school. -

Typhoid Over Diagnosis in Nakaseke District, June 2016

Public Health Fellowship Program – Field Epidemiology Track Typhoid Over diagnosis in Nakaseke District, June 2016 Dr. Kusiima Joy, MBChB-MHSR Fellow,2016 Typhoid Alert May June 2016 2016 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Notification Data Audit ,12 health Reviewed HMIS data facilities Nakaseke 84 cases/ 50,000 by FFETP(wk 15-21) Typhoid Outbreak verification exercise 323 Typhoid cases reported 2 Typhoid verification in Nakaseke District Objectives . Verify the existence of an outbreak . Verify reported diagnosis using standard case definition . Recommend public health action 3 Typhoid verification in Nakaseke District District location 4 Typhoid verification in Nakaseke District Facilities selected . Private hospital - Kiwoko . Government hospital - Nakaseke . Health center IV - Semuto . Health center III - Kapeeka 5 Typhoid verification in Nakaseke District Data collection . Extracted records from registers (1st/12/ 2015 to 14th/06/2016) . Discussed with clinicians & lab personnel . Took clinical history &examined typhoid suspects 6 Typhoid verification in Nakaseke District Standard case definition . Suspected case: Onset of fever ≥3days,negative malaria test, resident of Nakaseke district Plus any of following: chills, malaise, headache, sore throat, cough, abdominal pain, constipation, diarrhea . Probable case: Suspected case plus positive antigen test (Widal) . Confirmed case: Suspected case plus salmonella typhi (+) blood or stool by culture 7 Typhoid verification in Nakaseke District Data quality assessment . Reviewed laboratory -

BANKABLE-PROJECTS-2.Pdf

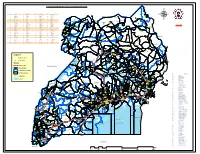

3RD EDITION • VIABLE INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITIES 2019/20 UGANDA - Reference Map S U D A N 0 50 100 150 200 km KOBOKO KAA BONG Moyo YUMBE Kaabong MOYO KITGUM Koboko Yumbe Kitgum Adjumani Page Arua ADJUMA NI Kotido ARUA Kibali PADER Gulu Pader KOT IDO GULU Town Okok MOROT O Moroto Nebbi NEBBI Acuwa APAC Oker D E M O C R A T I C Lira Apac LIRA Amuria R E P U B L I C Victoria Nile O F T H E C O N G O AMURIA U G A N D A Katakwi Nakapiripirit MASINDI Lake Lake Kwania Kaberamaido KATAKWI Albert Masindi Soroti NAKAPIRIPIRIT Bunia Amolatar Lake Shari Hoima Kyoga Kumi NAKASONGOLA Kapchorwa HOIMA KUMI 14 Nakasongola Sironko 13 KAMULI Pallisa Bukwa 12 KIBOGA NAKASEKE Kayunga Nkusi PALLISA Lugo KALIRO Mbale BUNDIBUGYO Victoria NileKamuli Kibaale Kiboga Kaliro Butaleja 10 11 Luweero 7 Manafwa KIBAA LE IGANGA 8 Bundibugyo Nakaseke 6 TORORO Fort Portal Iganga Kyenjojo Tororo Mubende JINJA KABAROLE KYENJOJO MIT YA NA Wakiso Jinja MUBENDE Bugiri Nzola Semliki Mukono Mayuge 9 Busia Kakamega Kasese Kamwenge Masaka Mityana MUKONO KAMPALA MAY UGE Katonga MPIGI Mpigi K E N Y A KASESE WAKISO BUGIRI Sembabule Ibanda Kisumu KIRUHURA MASAKA Lake Kalangala Winam Gulf Edward BUSHENYI Kiruhura Masaka Bushenyi KALANGALA Lake 4 Mbarara Victora Rakai 2 Rukungiri Kanungu ISINGIRO RAKAI Ntungamo Kasese 5 1 Kabale U N I T E D Kisoro 3 R E P U B L I C O F RWA N D A T A N Z A N I A Legend Elevation (meters) 5,000 and above National capital 4,000 - 5,000 First administrative level capital 3,000 - 4,000 Populated place 2,500 - 3,000 2,000 - 2,500 International boundary 1,500 - 2,000 First administrative level boundary 1,000 - 1,500 800 - 1,000 Districts 600 - 800 400 - 600 1. -

Legend " Wanseko " 159 !

CONSTITUENT MAP FOR UGANDA_ELECTORAL AREAS 2016 CONSTITUENT MAP FOR UGANDA GAZETTED ELECTORAL AREAS FOR 2016 GENERAL ELECTIONS CODE CONSTITUENCY CODE CONSTITUENCY CODE CONSTITUENCY CODE CONSTITUENCY 266 LAMWO CTY 51 TOROMA CTY 101 BULAMOGI CTY 154 ERUTR CTY NORTH 165 KOBOKO MC 52 KABERAMAIDO CTY 102 KIGULU CTY SOUTH 155 DOKOLO SOUTH CTY Pirre 1 BUSIRO CTY EST 53 SERERE CTY 103 KIGULU CTY NORTH 156 DOKOLO NORTH CTY !. Agoro 2 BUSIRO CTY NORTH 54 KASILO CTY 104 IGANGA MC 157 MOROTO CTY !. 58 3 BUSIRO CTY SOUTH 55 KACHUMBALU CTY 105 BUGWERI CTY 158 AJURI CTY SOUTH SUDAN Morungole 4 KYADDONDO CTY EST 56 BUKEDEA CTY 106 BUNYA CTY EST 159 KOLE SOUTH CTY Metuli Lotuturu !. !. Kimion 5 KYADDONDO CTY NORTH 57 DODOTH WEST CTY 107 BUNYA CTY SOUTH 160 KOLE NORTH CTY !. "57 !. 6 KIIRA MC 58 DODOTH EST CTY 108 BUNYA CTY WEST 161 OYAM CTY SOUTH Apok !. 7 EBB MC 59 TEPETH CTY 109 BUNGOKHO CTY SOUTH 162 OYAM CTY NORTH 8 MUKONO CTY SOUTH 60 MOROTO MC 110 BUNGOKHO CTY NORTH 163 KOBOKO MC 173 " 9 MUKONO CTY NORTH 61 MATHENUKO CTY 111 MBALE MC 164 VURA CTY 180 Madi Opei Loitanit Midigo Kaabong 10 NAKIFUMA CTY 62 PIAN CTY 112 KABALE MC 165 UPPER MADI CTY NIMULE Lokung Paloga !. !. µ !. "!. 11 BUIKWE CTY WEST 63 CHEKWIL CTY 113 MITYANA CTY SOUTH 166 TEREGO EST CTY Dufile "!. !. LAMWO !. KAABONG 177 YUMBE Nimule " Akilok 12 BUIKWE CTY SOUTH 64 BAMBA CTY 114 MITYANA CTY NORTH 168 ARUA MC Rumogi MOYO !. !. Oraba Ludara !. " Karenga 13 BUIKWE CTY NORTH 65 BUGHENDERA CTY 115 BUSUJJU 169 LOWER MADI CTY !. -

NAKASEKE DLG Q4 REPORT.Pdf

Local Government Quarterly Performance Report Vote: 569 Nakaseke District 2016/17 Quarter 4 Structure of Quarterly Performance Report Summary Quarterly Department Workplan Performance Cumulative Department Workplan Performance Location of Transfers to Lower Local Services and Capital Investments Submission checklist I hereby submit _________________________________________________________________________. This is in accordance with Paragraph 8 of the letter appointing me as an Accounting Officer for Vote:569 Nakaseke District for FY 2016/17. I confirm that the information provided in this report represents the actual performance achieved by the Local Government for the period under review. Name and Signature: Chief Administrative Officer, Nakaseke District Date: 8/23/2017 cc. The LCV Chairperson (District)/ The Mayor (Municipality) Page 1 Local Government Quarterly Performance Report Vote: 569 Nakaseke District 2016/17 Quarter 4 Summary: Overview of Revenues and Expenditures Overall Revenue Performance Cumulative Receipts Performance Approved Budget Cumulative % UShs 000's Receipts Budget Received 1. Locally Raised Revenues 1,338,786 1,704,820 127% 2a. Discretionary Government Transfers 3,314,474 3,260,284 98% 2b. Conditional Government Transfers 16,270,489 15,459,486 95% 2c. Other Government Transfers 948,643 966,847 102% 4. Donor Funding 22,900 Total Revenues 21,872,393 21,414,338 98% Overall Expenditure Performance Cumulative Releases and Expenditure Perfromance Approved Budget Cumulative Cumulative % % % UShs 000's Releases Expenditure -

![Uganda Health Facilities Survey 2002 [FR140]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8904/uganda-health-facilities-survey-2002-fr140-1738904.webp)

Uganda Health Facilities Survey 2002 [FR140]

Uganda Health Facilities Survey 2002 Ministry of Health Kampala, Uganda ORC Macro MEASURE DHS+ Calverton, Maryland, USA John Snow, Inc./DELIVER Arlington, Virginia, USA JSI Research & Training Institute, Inc./ Uganda AIDS/HIV Integrated Model District Programme (AIM) Kampala, Uganda June 2003 Contributors: John Snow, Inc./DELIVER JSI Research and Training Institute, Inc./AIM Dana Aronovich Evas Kansiime Allison Farnum Cochran Maurice Adams Erika Ronnow Ministry of Health ORC Macro F. G. Omaswa Gregory Pappas H. Kyabaggu Eddie Mukooyo Martin O. Oteba This report presents findings from the 2002 Uganda Health Facilities Survey (UHFS 2002) carried out by the Uganda Ministry of Health. ORC Macro (MEASURE DHS+) and John Snow, Inc. (DELIVER) provided technical assistance. Other organizations contributing to the project were the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC/Uganda), the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID/Uganda), and the JSI Research and Training Institute, Inc., AIDS/HIV Integrated Model District Programme (AIM). MEASURE DHS+, a USAID-funded project, assists countries worldwide in the collection and use of data to monitor and evaluate population, health, and nutrition programs. Information about the Uganda Health Facilities Survey or about the MEASURE DHS+ project can be obtained by contacting: MEASURE DHS+, ORC Macro, 11785 Beltsville Drive, Suite 300, Calverton, MD 20705 (Telephone 301-572-0200; Fax 301-572-0999; E-mail [email protected]; Internet: www.measuredhs.com). DELIVER, a worldwide technical assistance support project, is funded by the Commodities Security and Logistics Division (CSL) of the Office of Population and Reproductive Health of the Bureau for Global Health (GH) of the U.S. -

Vote:569 Nakaseke District Quarter4

Local Government Quarterly Performance Report FY 2019/20 Vote:569 Nakaseke District Quarter4 Terms and Conditions I hereby submit Quarter 4 performance progress report. This is in accordance with Paragraph 8 of the letter appointing me as an Accounting Officer for Vote:569 Nakaseke District for FY 2019/20. I confirm that the information provided in this report represents the actual performance achieved by the Local Government for the period under review. Katotoroma John Date: 25/08/2020 cc. The LCV Chairperson (District) / The Mayor (Municipality) 1 Local Government Quarterly Performance Report FY 2019/20 Vote:569 Nakaseke District Quarter4 Summary: Overview of Revenues and Expenditures Overall Revenue Performance Ushs Thousands Approved Budget Cumulative Receipts % of Budget Received Locally Raised Revenues 1,920,021 666,949 35% Discretionary Government 3,701,682 3,677,141 99% Transfers Conditional Government Transfers 21,605,823 22,182,854 103% Other Government Transfers 1,888,246 1,870,522 99% External Financing 412,232 443,506 108% Total Revenues shares 29,528,003 28,840,972 98% Overall Expenditure Performance by Workplan Ushs Thousands Approved Cumulative Cumulative % Budget % Budget % Releases Budget Releases Expenditure Released Spent Spent Administration 2,844,971 3,958,380 3,863,561 139% 136% 98% Finance 920,368 465,593 465,593 51% 51% 100% Statutory Bodies 1,278,586 708,290 704,680 55% 55% 99% Production and Marketing 1,199,600 1,106,894 1,106,893 92% 92% 100% Health 6,782,333 6,994,819 6,650,197 103% 98% 95% Education 13,126,979 -

Iud Contraceptive Use Among Women of Reproductive Age

IUD CONTRACEPTIVE USE AMONG WOMEN OF REPRODUCTIVE AGE: A QUALITATIVE STUDY AT THE FAMILY PLANNING CLINIC OF NAKASEKE GENERAL HOSPITAL BY NAMBALIRWA TEDDY 15/U/20585/PS SUPERVISOR: Dr. SCOVIA NALUGO MBALINDA (PhD, MSc, BScN) A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO MAKERERE UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF NURSING IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT FOR AWARD OF A DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF SCIENCE IN NURSING OF MAKERERE UNIVERSITY MAY, 2019 DECLARATION i DEDICATION I dedicate this dissertation report to my father Mr. Male Alozious, my brother Kayongo Joseph and my husband Mr. Ddumba Richard who have been a great source of encouragement and financial supporters throughout my academic years. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I thank the almighty God, for the love, grace, guidance, wisdom, understanding, providence and strength He has granted me to make this study a reality. Throughout the writing of this dissertation, I have received a great deal of support and assistance. I would first like to thank my supervisor, Dr. Mbalinda Nalugo Scovia, whose expertise was priceless in formulating research topic and methodology in particular and helped me to do this wonderful study on the topic IUD use among WRA, which has helped in doing findings and to know many of the women‟s experiences. A would also like to express my special thanks of gratitude to my colleagues in year four 2019 nursing school for their wonderful collaboration. You supported greatly and were always willing to help me. I would also like to thank my tutors for their valuable guidance. You provided me the tools that I need to choose the right direction and successfully completed my dissertation.