“The Source of Our Power”: Female Heroes and Restorative

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

215-345-7966 BLUM-MOORE REPORTING SERVICES, INC. 1 BEFORE NEW HOPE BOROUGH COUNCIL in Re: Special Meeti

1 BEFORE NEW HOPE BOROUGH COUNCIL In Re: Special Meeting - - - - MONDAY, NOVEMBER 5, 2018 - - - - A public meeting was held at the Borough Municipal Building, 125 New Street, New Hope, Pennsylvania 18938, commencing at 7:00 p.m. on the day and date above set forth, before Tara Wilson, Professional Reporter and Notary Public in and for the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. - - - - BLUM-MOORE REPORTING SERVICES, INC. 350 SOUTH MAIN STREET, SUITE 203 DOYLESTOWN, PENNSYLVANIA 18901 (215) 345-7966 BLUM-MOORE REPORTING SERVICES, INC. www.blummoore.com 215-345-7966 2 4 1 BOROUGH COUNCIL: 1 MS. KINGSLEY: I'd like to call the 2 Mayor Laurence D. Keller 2 meeting to order. All rise for the pledge of Alison Kingsley, President 3 Connie Gering, Vice-President 3 allegiance. Tina Leifer Rettig (Late arrival) 4 (Pledge of allegiance was recited.) 4 Peter Meyer Ken Maisel 5 MS. KINGSLEY: One special 5 Dan Dougherty 6 announcement, they'll be an executive session 6 E.J. Lee, Borough Manager 7 after this meeting. T.J. Walsh, Esquire, Solicitor 7 8 Tonight's meeting is for the purpose of ALSO PRESENT: 9 hearing the zoning application for the Mansion 8 10 Inn. Chief Michael Cummings 9 New Hope Police Department 11 UNIDENTIFIED SPEAKER: Can't hear you. 10 Jim Ennis, Borough Zoning Officer 12 MS. KINGSLEY: The purpose of tonight's 11 Curtin & Heefner, LLP 13 By Paul Cohen, Esquire meeting is to the hearing the zoning application 12 1040 Stony Hill Road 14 for the Mansion Inn. And our solicitor T.J. Suite 150 15 Walsh, will frame the purpose and the function of 13 Yardley, PA 19067 For the Applicant - Mansion Inn 16 the meeting this evening. -

Would You Understand What I Meant If I Said I Was Only Human?”

”Would you understand what I meant if I said I was only human?” The Image of the Vampire in Stephenie Meyer’s Twilight and Charlaine Harris’s Dead Until Dark Jessica Dimming Fakulteten för humaniora och samhällsvetenskap English IV 15hp Supervisor Magnus Ullén Examiner Adrian Velicu HT 2012 Abstract In this essay I have decided to look at two very popular vampire novels today, Dead Until Dark by Charlaine Harris and Twilight by Stephenie Meyer. The focus of this essay is to look at the similarities and differences between these two novels and compare them to each other but also to the original legend of the vampire; this by using Dracula and other famous vampire stories to get an image of the vampire of pop-culture. I look at the features of the vampires, their abilities and different skills, and also sex and sexuality and how it is represented in these different stories. Even though the novels attract a wide audience they are written for a younger one and have a love story as its center. In this essay I give my opinion and view of the vampires and what I believe to be interesting with the morals and looks of the vampires as one of the different aspects. 2 Content Introduction 3 The Gothic novel 6 The legend of the vampire 7 Setting 10 Narrator 38 Features of the vampires in Twilight 43 Features of the vampires in Dead Until Dark 53 Vampires as sexual objects 67 Love and sexuality in Twilight 75 Love and sexuality in Dead Until Dark 86 Conclusion 95 Works cited 30 3 Introduction Dead Until Dark and Twilight by top selling authors Charlaine Harris and Stephenie Meyer are both novels written for young adults, somewhere between the ages of 14-24, with one major theme in common, vampires. -

A Portrait of Fandom Women in The

DAUGHTERS OF THE DIGITAL: A PORTRAIT OF FANDOM WOMEN IN THE CONTEMPORARY INTERNET AGE ____________________________________ A Thesis Presented to The Honors TutoriAl College Ohio University _______________________________________ In PArtiAl Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation from the Honors TutoriAl College with the degree of Bachelor of Science in Journalism ______________________________________ by DelAney P. Murray April 2020 Murray 1 This thesis has been approved by The Honors TutoriAl College and the Department of Journalism __________________________ Dr. Eve Ng, AssociAte Professor, MediA Arts & Studies and Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Thesis Adviser ___________________________ Dr. Bernhard Debatin Director of Studies, Journalism ___________________________ Dr. Donal Skinner DeAn, Honors TutoriAl College ___________________________ Murray 2 Abstract MediA fandom — defined here by the curation of fiction, art, “zines” (independently printed mAgazines) and other forms of mediA creAted by fans of various pop culture franchises — is a rich subculture mAinly led by women and other mArginalized groups that has attracted mAinstreAm mediA attention in the past decAde. However, journalistic coverage of mediA fandom cAn be misinformed and include condescending framing. In order to remedy negatively biAsed framing seen in journalistic reporting on fandom, I wrote my own long form feAture showing the modern stAte of FAndom based on the generation of lAte millenniAl women who engaged in fandom between the eArly age of the Internet and today. This piece is mAinly focused on the modern experiences of women in fandom spaces and how they balAnce a lifelong connection to fandom, professional and personal connections, and ongoing issues they experience within fandom. My study is also contextualized by my studies in the contemporary history of mediA fan culture in the Internet age, beginning in the 1990’s And to the present day. -

Buffy at Play: Tricksters, Deconstruction, and Chaos

BUFFY AT PLAY: TRICKSTERS, DECONSTRUCTION, AND CHAOS AT WORK IN THE WHEDONVERSE by Brita Marie Graham A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English MONTANA STATE UNIVERSTIY Bozeman, Montana April 2007 © COPYRIGHT by Brita Marie Graham 2007 All Rights Reserved ii APPROVAL Of a thesis submitted by Brita Marie Graham This thesis has been read by each member of the thesis committee and has been found to be satisfactory regarding content, English usage, format, citations, bibliographic style, and consistency, and is ready for submission to the Division of Graduate Education. Dr. Linda Karell, Committee Chair Approved for the Department of English Dr. Linda Karell, Department Head Approved for the Division of Graduate Education Dr. Carl A. Fox, Vice Provost iii STATEMENT OF PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a master’s degree at Montana State University, I agree that the Library shall make it availably to borrowers under rules of the Library. If I have indicated my intention to copyright this thesis by including a copyright notice page, copying is allowable only for scholarly purposes, consistent with “fair use” as prescribed in the U.S. Copyright Law. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this thesis in whole or in parts may be granted only by the copyright holder. Brita Marie Graham April 2007 iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS In gratitude, I wish to acknowledge all of the exceptional faculty members of Montana State University’s English Department, who encouraged me along the way and promoted my desire to pursue a graduate degree. -

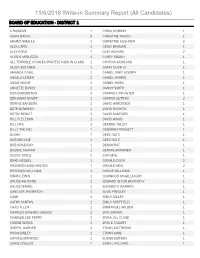

11/6/2018 Write-In Summary Report (All Candidates) BOARD of EDUCATION - DISTRICT 1

11/6/2018 Write-in Summary Report (All Candidates) BOARD OF EDUCATION - DISTRICT 1 A RAINEAR 1 CHRIS MURRAY 1 ADAM HATCH 2 CHRISTINE ASHOO 1 AHMED SMALLS 1 CHRISTINE KUSHNER 2 ALEX CARR 1 CINDY BEAMAN 1 ALEX FORD 1 CLAY WILKINS 2 ALICE E VERLEZZA 1 COREY BRUSH 1 ALL TERRIBLE CHOICES PROTECT KIDS IN CLASS 1 CYNTHIA WOOLARD 1 ALLEN BUTCHER 1 DAFFY DUCK III 1 AMANDA GOWL 1 DANIEL GREY SCURRY 1 ANGELA LEISER 2 DANIEL HARRIS 1 ANGIE WIGHT 1 DANIEL HORN 1 ANNETTE BUSBY 1 DANNY SMITH 1 BEN DOBERSTEIN 2 DAPHNE LANCASTER 1 BENJAMIN DOVER 1 DAPHNE SUTTON 2 BERNIE SANDERS 1 DAVID HARDISTER 1 BETH BOWMAN 1 DAVID RUNYON 1 BETSY BENOIT 1 DAVID SANFORD 1 BILL FLELEHAN 1 DAVID WOOD 1 BILL NYE 1 DEANNE TALLEY 1 BILLY THE KID 1 DEBORAH PRICKETT 1 BLANK 7 DEEZ NUTS 1 BOB MELONE 1 DEEZ NUTZ 1 BOB SPAZIANO 1 DEMOCRAT 1 BOBBIE CAVNAR 1 DENNIS BRAWNER 1 BOBBY JONES 1 DON MIAL 1 BRAD HESSEL 1 DONALD DUCK 2 BRANDON WASHINGTON 1 DONALD MIAL 2 BRANNON WILLIAMS 1 DONNE WILLIAMS 1 BRIAN LEWIS 1 DURWOOD MCGILLACUDY 1 BRUCE ASHFORD 1 EDWARD ALTON HUNTER IV 1 BRUCE MAMEL 1 ELIZABETH WARREN 1 CANDLER THORNTON 1 ELVIS PRESLEY 1 CASH 1 EMILY JOLLEY 1 CATHY SANTOS 1 EMILY SHEFFIELD 1 CHAD ALLEN 1 EMMANUEL WILDER 1 CHARLES EDWARD CHEESE 1 ERIC BROWN 1 CHARLES LEE PERRY 1 ERIKA JILL CLOSE 1 CHERIE WIGGS 1 ERIN E O'LEARY 1 CHERYL GARNER 1 ETHAN MATTHEWS 1 CHRIS BAILEY 1 ETHAN SIMS 1 CHRIS BJORNSTED 1 EUSHA BURTON 1 CHRIS COLLUM 1 EVAN L POLLARD 1 11/6/2018 Write-in Summary Report (All Candidates) BOARD OF EDUCATION - DISTRICT 1 EVERITT 1 JIMMY ALSTON 1 FELIX KEYES 1 JO ANNE -

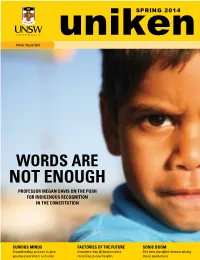

Not Enough Professor Megan Davis on the Push for Indigenous Recognition in the Constitution

Never Stand Still WORDS ARE NOT ENOUGH PROFESSOR MEGAN DAVIS ON THE PUSH FOR INDIGENOUS RECOGNITION IN THE CONSTITUTION CURIOUS MINDS FACTORIES OF THE FUTURE SONIC BOOM Crowdfunding science to give A modern-day alchemist takes The new discipline democratising young researchers a chance recycling to new heights music production UNIKEN • Contents SPRING 2014 COVER STORY Words are not enough 12 FEATURES Dark side of the net 6 Curious minds 7 A new era 8 The great transformer 10 Photo: Man and machine 15 Grant Turner/ Mediakoo The parenting trap 16 Quantum tern 18 Beautiful but a threat 19 YOUR TIME STarts now … Sense of place 20 ANDREW WELLS, UNIVERSITY LIBRARIAN Sign of the times 21 Ripping down all the signs that arrived at UNSW he had 25 years’ library LONG FORM said “Don’t rearrange the furniture” was experience and had witnessed the biggest Surviving in the city 22 the first thing Andrew Wells did when transition libraries have seen to date – the he started working as the head of the move online. “In the print world libraries held the ARTS University Library. “The next day they’d be up again, and jewels and if anyone wanted them they Sonic boom 24 I’d tear them back down. I kept saying, had to come to us – it doesn’t work like Museums of the future 25 ‘This is the students’ library. Not ours.’ ” that anymore, libraries have to work a lot More than a decade later Wells has harder now.” UNSW books 26 created a library he admits some people Your dream job: A physician. -

Fragile Bodies in Stephenie Meyer's Twilight Series

Cultivating Perspectives: Fragile Bodies in Stephenie Meyer’s Twilight Series by Heather Simeney MacLeod A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Department of English and Film Studies University of Alberta © Heather Simeney MacLeod, 2014 ABSTRACT This dissertation project exposes the troubling engagement with classifications of materiality within text and bodies in Stephenie Meyer’s contemporary American vampire narrative, the Twilight Series (2005-2008). It does so by disclosing the troubling readings inherent in genre; revealing problematic representations in the gendered body of the protagonist, Bella Swan; exposing current cultural constructions of the adolescent female; demonstrating the nuclear structure of the family as inextricably connected to an iconic image of the trinity— man, woman, and child; and uncovering a chronicle of the body of the racialized “other.” That is to say, this project analyzes five persistent perspectives of the body—gendered, adolescent, transforming, reproducing, and embodying a “contact zone”—while relying on the methodologies of new feminist materialisms, posthumanism, postfeminism and vampire literary criticism. These conditions are characteristic of the “genre shift” in contemporary American vampire narrative in general, meaning that current vampire fiction tends to shift outside of the boundaries of its own classification, as in the case of Meyer’s material, which is read by a diverse readership outside of its Young Adult categorization. As such, this project closely examines the vampire exposed in Meyer’s remarkably popular text, as well as key texts published in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, such as Joss Whedon’s television series Buffy the Vampire Slayer (1997-2003), Alan Ball’s HBO series True Blood (2009-2014), Kathryn Bigelow’s Near Dark (1987) and Joel Schumacher’s The Lost Boys (1987). -

18Th Annual Immunology Retreat

th 18 Annual Immunology Retreat Friday to Sunday, November 18-20, 2005 Willow Valley Resort and Conference Center 2416 Willow Street Pike Lancaster, PA 17602-4898 Friday, November 18, 2005 3-6 pm Registration and Check-in, Main Lobby When you arrive, please set up posters for the remainder of the conference in Statesman C/D 5:30-7pm Dinner Smorgasbord, Terrace Dining Room 7-10pm Session I, Statesman Hall A/B/C/D Session Chairs: Ginny Shapiro and Jan Burkhardt 7-7:15pm Welcome, Steve Reiner 7:15-8:30 pm Keynote Speaker, Christophe Benoist, M.D., Ph.D. Member, National Academy of Sciences Section on Immunology and Immunogenetics Joslin Diabetes Center, Department of Medicine Brigham and Women’s Hospital 8:30-8:50 pm Break 8:50-9:20 pm Stefania Gallucci, MD, Assistant Professor, Pediatrics, CHOP "Dendritic cells, Interferons and Lupus" 9:20-9:50 pm John Wherry, PhD, Assistant Professor, Immunology Program, Wistar "Memory CD8 T cell differentiation following acute versus chronic infection" 9:50 pm End of session Saturday, November 19, 2005 8-9am Breakfast Smorgasbord, Terrace Dining Room 9-12am Session II, Statesman Hall A/B/C/D Session Chair: Ben Schwarz 9:00-9:25 Ben Schwarz, Bhandoola Lab “From bone marrow to the thymus: a prerequisite for T cell development” 9:25-9:50 Stanley Adoro, Singer Lab “Cytokine dependence of CD8α coreceptor expression and CD8+ lineage choice” 9:50-10:15 Terry Fang, Pear Lab “Notch is a critical regulator of type 2 immunity” 10:15-10:45 Break 10:45-11:10 Marion Pepper, Hunter Lab “Tracking the generation of the -

Buffy the Post-Anarchist Vampire Slayer

Buffy the Post-Anarchist Vampire Slayer Lewis Call 2011 Contents ‘WE’VE GOT IMPORTANT WORK HERE. A LOT OF FILING, GIVING THINGS NAMES.’ 5 Post-Anarchist Themes in Late Season Four of Buffy ................ 5 References .......................................... 12 2 The publication of Post-Anarchism: A Reader confirms what many of us have suspected (and cautiously hoped for) these past few years: a kind of post-anarchist moment has arrived. Ben- jamin Franks has argued that this moment has already enabled a small but identifiable post- anarchist movement to emerge; he quite sensibly names Todd May, Saul Newman, Bob Black, Hakim Bey and me as members of this movement (2007: 127). Legend has it that Bey got the whole thing started back in the 1980s, when he called for a ‘post-anarchism anarchy’ which would build on the legacy of Situationism in order to reinvigorate anarchism from within (1985: 62). Interestingly, Bey identified popular entertainment as a vehicle for ‘radical re-education’ (ibid.). It is in this spirit that I offer my post-anarchist reading of Joss Whedon’s popular fantasy programme Buffy the Vampire Slayer. My text will be Buffy’s fourth season. This season undeni- ably represents Buffy’s anarchist moment; I will argue that season four also offers its audience an accessible yet sophisticated post-anarchist politics. But what does a post-anarchist politics look like? Newman has pointed out that post-anarchism is not ‘after’ anarchism and does not seek to dismiss the classical anarchist tradition; rather, post- anarchism attempts to radicalize the possibilities of that tradition (2008: 101). -

2019–2020 Annual Report

ANNUAL REPORT 2019–20 Dear Friends, This annual report was finalized in a world that was unthinkable when the year began. Even though such a report typically looks back, this unprecedented moment calls for looking forward. The Museum is now an all-digital, all-the-time enterprise, for how long we do not know. But that alone is not enough. This is a time for learning and growing. Our digital education resources and virtual trainings and programs must serve our many diverse partners and audiences—teachers, faculty, students, leaders, and the general public. But, we have learned that in digital education, quantity is not quality, and that virtual education is much more complex than we imagined. Demand for our online resources and teaching support has soared, and we are experimenting and reimagining our work for this new world. Our role has always been to help build and lead the fields of Holocaust scholarship and education as well as genocide prevention. Now these fields face challenges and opportunities as never before. Thanks to your ongoing generosity, the Museum is well positioned to learn from this crisis and grow into an even stronger, more impactful institution, whose educational message is more urgent than ever. Thank you, Howard M. Lorber, Chairman Allan M. Holt, Vice Chairman Sara J. Bloomfield, Director FOUNDERS SOCIETY Gifts as of August 7, 2020 The Museum is deeply grateful to our leading donors, whose cumulative gifts of $1 million or more make our far-reaching impact possible. GUARDIANS OF MEMORY PILLARS OF MEMORY Planethood Foundation, Inc. The Chrysler Corporation Fund Doris and Simon* Konover Judith B. -

Circumstantially Hurt.Pdf

Disclaimer: THIS STORY IS COPYRIGHT © 2002-2021 BY MultiMapper. THIS STORY IS FULLY PROTECTED UNDER THE UNITED STATES COPYRIGHT LAWS © 17 USC §§ 101, 102(a), 302(a). ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. PLACING OR POSTING THIS STORY ON ANY WEBSITE, OR DISTRIBUTION OF THIS WORK IN ANY WAY (PARTS OR WHOLE) WITHOUT THE EXPLICIT CONSENT OF THE AUTHOR IS STRICTLY PROHIBITED. ANY AND ALL COPYRIGHT INFRINGEMENTS WILL BE PROSECUTED TO THE FULLEST EXTENT OF THE LAW. DISTRIBUTION FOR COMMERCIAL GAIN, INCLUDING, BUT NOT LIMITED TO, POSTING ON SITES OR NEWSGROUPS, DISTRIBUTION AS PARTS OR IN BOOK FORM (EITHER AS A WHOLE OR PART OF A COMPILATION) WITH OR WITHOUT A FEE, OR DISTRIBUTION ON CD, DVD, OR ANY OTHER ELECTRONIC MEDIA WITH OR WITHOUT A FEE, IS EXPRESSLY PROHIBITED WITHOUT THE AUTHOR'S WRITTEN CONSENT. YOU MAY DOWNLOAD ONE (1) COPY OF THIS STORY FOR PERSONAL USE; ANY AND ALL COMMERCIAL USE EXCEPTING EDUCATIONAL INSTITUTIONS REQUIRES THE AUTHORS WRITTEN CONSENT. THE AUTHOR MAY BE CONTACTED AT: [email protected]. BY CONTINUING TO READ THIS STORY, YOU ARE STATING THAT YOU HAVE READ AND AGREED TO ALL DISCLAIMERS FOUND ON THE DISCLAIMER PAGE WHICH IS USED TO ACCESS THIS STORY. IF YOU CAME FROM ANOTHER SITE AND DID NOT VIEW THIS PAGE, YOU ARE REQUIRED TO VIEW IT BY FOLLOWING THE NORMAL NAVIGATION STEPS FOUND ON BENT & TWISTED AT WWW.BENTANDTWISTED.US. FAILURE TO DO SO RELEASES ALL PERSONS AND ENTITIES ASSOCIATED WITH THIS STORY AND/OR SITE FROM ANY CONSEQUENCES OF YOU ACCESSING THIS STORY. This story is a work of fiction. -

Confronting Eternity

Confronting Eternity Strange (Im)mortalities, and States of Undying in Popular Fiction January 27, 2014 Edwin Bruce Bacon 46250931 [email protected] Department of English University of Canterbury, Christchurch, New Zealand Supervisors: Dr. Anna Smith and Dr. Mary Wiles To Glen and Benjamin, The inspirations for immortality. ii Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS .....................................................................................................................III THESIS ABSTRACT .......................................................................................................................... V AN INTRODUCTION TO IMMORTALITY.......................................................................................... VI GLOSSARY OF NEOLOGISMS AND UNIQUE PHRASES .................................................................... IX CHAPTER ONE: THE MIRIFIC MORTALITIES OF DOCTOR WHO ......................................................... 1 PHOENICAL MEN, AND “THE MASTER RACE” ............................................................................................. 1 Phoenical Bodies, Tardevism, and “The Long View” ................................................................... 3 Moriartesque Supervillainies: The Master as a Moriarty .......................................................... 13 The Master as a Cambion, as a Merl(i/y)n, and as a Misanthrope ........................................... 16 The Master as Misanthrope, and as Many...............................................................................