Sartre's Account of Human Freedom in Being and Nothingness

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Review of Being and Nothingness

Being and Nothingness: An Essay in Phenomenological Ontology by Jean-Paul Sartre, translated by Sarah Richmond. Abingdon: Routledge, 2018. Jonathan Webber Review published in Mind 2019 Author’s post-print. Please cite only published version. Legend has it that when Jean-Paul Sartre’s first epic tome L’Être et le néant appeared in 1943 the publishers were rather surprised by how well it sold. Who were all these people in the midst of war yet eager to read a 722-page philosophical analysis of the structures of human existence? They discovered that the book, which weighed exactly one kilo, was mostly selling to greengrocers, who were using it to replace the kilo weights that had been confiscated by the Nazis to be melted down for munitions. Sarah Richmond’s superb new translation weighs in at nearly a kilo and a half. The text itself is supplemented by a wealth of explanatory and analytical material. Richmond has taken full advantage of the extensive scholarly and critical analyses of Sartre’s book published over the past three-quarters of a century. The book has been translated into English only once before, by Hazel Barnes over sixty years ago. Richmond’s strategy has not been to edit that version, but to translate the text anew, informed by its reception in both its original form and its Barnes translation. Richmond traces the main contours of this reception in her introduction to the book, which relates the text to the main currents of anglophone and European thought since the war and, in so doing, indicates the influences on her own reading of the text. -

The Rhetoric of Imagination in Sartre's Philosophy and Prose

Language and Engagement: The Rhetoric of Imagination in Sartre’s Philosophy and Prose Merel Aalders (11753560) Master Thesis UvA Philosophy First Reader: dr. A. van Rooden Second reader: dr. E.C Brouwer September 2018 1 Table of Contents Abstract ................................................................................................................................. 3 Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 4 1. Early Engagement: A Literature of Praxis ........................................................................ 8 I Being and Nothingness: Consciousness and Freedom .................................................... 8 II What is Literature?: Consciousness, Freedom and Creative Imagination ................. 10 III The Relationship between Reader and Writer ........................................................... 14 IV The Situation of the Writer .......................................................................................... 15 V Between Language and World ...................................................................................... 19 2. Late Engagement: Materiality, Alienation and Ambiguity ............................................ 25 VI Engagement Evolves ..................................................................................................... 25 VII Disinformation and the Inexpressible ........................................................................ 28 VIII Materiality, Ambiguity -

European Academic Research

EUROPEAN ACADEMIC RESEARCH Vol. II, Issue 9/ December 2014 Impact Factor: 3.1 (UIF) ISSN 2286-4822 DRJI Value: 5.9 (B+) www.euacademic.org Condemned to be Free: Orestes in Sartre’s The Flies MOHSIN HASSAN KHAN Research Scholar Department of English A.M.U., Aligarh, India Abstract: Jean Paul Sartre’s Orestes’ is one of the strong characters as far as literary sketch of any existential character is concerned. Embodiment of Sartrean philosophy, Orestes, in the play The Flies (1943) is a representation of the philosophy of freedom in which Sartre has put his literary thesis with the philosophic. In doing so with the character of Orestes, he comes back again to his lifelong pursuit of freedom and tries to explore it in the most possible and natural sense making freedom as an absolute and a strong value. The idea of freedom has been smoothly sketched in the play and its strident treatment matches the doctrines of freedom by the playwright. In this play, Sartre expresses the idea of condemned freedom and an attempt has been made in this paper to show this particular Sartrean brand of freedom expressed in Orestes. Key words: Existentialism, Existence, Freedom, Condemned, Absolute, No. Enlightenment Jean Paul Sartre, an avowed existentialist and a militant atheist, being at the centre of the modern philosophy is a very important figure in French existentialism. Truly a philosopher in the traditional sense like Heidegger and also a political figure protesting in the student’s revolution of 1968 in which he was almost close to becoming a rebel, he is a fine amalgamation of 20th century thought in which letters and actions go together 11954 Mohsin Hassan Khan- Condemned to be Free: Orestes in Sartre’s The Flies simultaneously. -

Existential Aspect of Being: Interpreting J. P. Sartre's Philosophy

Existential aspect of Being: Interpreting J. P. Sartre’s Philosophy Ivan V. Kuzin, Alexander A. Drikker & Eugene A. Makovetsky Saint Petersburg State University, Russia Abstract The article discusses rationalistic and existential approaches to the problem of existence. The comparison of Sartre's pre-reflective cogito and Descartes' reflective cogito makes it possible to define how Sartre’s thought moves from the thing to consciousness and from consciousness to the thing. At the same time, in Being and Nothingness Sartre does not only define the existence of the thing in its passivity—which in many respects corresponds to Descartes' philosophy, but also as an open orientation towards consciousness, the latter concept not being fully developed by him. This statement may be regarded as a hidden component of Sartre’s key thesis about the role of the Other in the verification of our existence. The most important factor in understanding this is the concept of the look. Detailed analysis of Sartre’s theses in Being and Nothingness enables us to demonstrate that the concept of the look makes it possible to consider the identity of being-in-itself and being-for-itself (consciousness). Keywords: Sartre, rationalism, existentialism, thing, being, the look, existence, nothingness, consciousness, the Other 1. Introduction E. Husserl said that being of the object is such “that it is cognisable in itself” (“daß es in seinem Wesen liegt, erkennbar zu sein”). (Ingarden 1992: 176) This statement is important if we are to accept the fact that the possibility of looking at the object correlates with being of the object itself. -

Anarchism in Australia

The Anarchist Library (Mirror) Anti-Copyright Anarchism in Australia Bob James Bob James Anarchism in Australia 2009 James, Bob. “Anarchism, Australia.” In The International Encyclopedia of Revolution and Protest: 1500 to the Present, edited by Immanuel Ness, 105–108. Vol. 1. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009. Gale eBooks (accessed June 22, 2021). usa.anarchistlibraries.net 2009 James, B. (Ed.) (1983) What is Communism? And Other Essays by JA Andrews. Prahran, Victoria: Libertarian Resources/ Backyard Press. James, B. (Ed.) (1986) Anarchism in Australia – An Anthology. Prepared for the Australian Anarchist Centennial Celebra- tion, Melbourne, May 1–4, in a limited edition. Melbourne: Bob James. James, B. (1986) Anarchism and State Violence in Sydney and Melbourne, 1886–1896. Melbourne: Bob James. Lane, E. (Jack Cade) (1939) Dawn to Dusk. N. P. William Brooks. Lane, W. (J. Miller) (1891/1980) Working Mans’Paradise. Syd- ney: Sydney University Press. 11 Legal Service and the Free Store movement; Digger, Living Day- lights, and Nation Review were important magazines to emerge from the ferment. With the major events of the 1960s and 1970s so heavily in- fluenced by overseas anarchists, local libertarians, in addition Contents to those mentioned, were able to generate sufficient strength “down under” to again attempt broad-scale, formal organiza- tion. In particular, Andrew Giles-Peters, an academic at La References And Suggested Readings . 10 Trobe University (Melbourne) fought to have local anarchists come to serious grips with Bakunin and Marxist politics within a Federation of Australian Anarchists format which produced a series of documents. Annual conferences that he, Brian Laver, Drew Hutton, and others organized in the early 1970s were sometimes disrupted by Spontaneists, including Peter McGre- gor, who went on to become a one-man team stirring many national and international issues. -

Existentialism in Two Plays of Jean-Paul Sartre

Journal of English and Literature Vol. 3(3), 50-54, March 2012 Available online at http://www.academicjournals.org/IJEL DOI:10.5897/IJEL11.042 ISSN 2141-2626 ©2012 Academic Journals Review Existentialism in two plays of Jean-Paul Sartre Cagri Tugrul Mart Department of Languages, Ishik University, Erbil, Iraq. E-mail: [email protected]. Tel: (964) 7503086122. Accepted 26 January, 2012 Existentialism is the movement in the nineteenth and twentieth century philosophy that addresses fundamental problems of human existence: death, anxiety, political, religious and sexual commitment, freedom and responsibility, the meaning of existence itself (Priest, 2001: 10). This study tries to define what existentialism is and stresses themes of existentialism. This research finally points out these themes of existentialism by studying on two existentialist drama plays written by Jean-Paul Sartre who was a prominent existentialist writer. The plays by Sartre studied in this research are ‘The Flies’ and ‘Dirty Hands’. Key words: Existentialism, freedom, absurdity, anguish, despair, nothingness. INTRODUCTION Existentialism is the philosophy that makes an religious, political, or sexual commitment? How should authentically human life possible in a meaningless and we face death? (Priest, 2001: 29). We can briefly define absurd world (Panza and Gale, 2008: 28). It is essentially existentialism as: ‘existentialism maintains that, in man, the search of the condition of man, the state of being and in man alone, existence precedes essence’. This free, and man's always using his freedom. Existentialism simply means that man first is, and only subsequently is, is to say that something exists, is to say that it is. -

Nausea and the Adventures of the Narrative Self Ben Roth1

How Sartre, Philosopher, Misreads Sartre, Novelist: Nausea and the Adventures of the Narrative Self Ben Roth1 Besides, art is fun and for fun, it has innumerable intentions and charms. Literature interests us on different levels in different fashions. It is full of tricks and magic and deliberate mystification. Literature entertains, it does many things, and philosophy does one thing. Iris Murdoch (1997, p. 4) If there is something comforting—religious, if you want—about paranoia, there is still also anti-paranoia, where nothing is connected to anything, a condition not many of us can bear for long. Thomas Pynchon, Gravity's Rainbow (p. 434) Both those who write in favor of and against the notion of the narrative self cite Sartre and his novel Nausea as exemplary opponents of it. Alasdair MacIntyre, a central proponent of the narrative self, writes: “Sartre makes Antoine Roquentin argue not just [...] that narrative is very different from life, but that to present human life in the form of a narrative is always to falsify it” (1984, p. 214). Galen Strawson, a critic of narrativity, writes that “Sartre sees the narrative, story-telling impulse as a defect, regrettable. [...] He thinks human Narrativity is essentially a matter of bad faith, of radical (and typically irremediable) inauthenticity” (2004, p. 435). I think that this type of interpretation of Nausea is blindered and bad and relies on an impoverished approach to reading fiction typical of philosophers: of taking one character at one moment as mouthpiece for both a novel as a whole and author behind it. Beginning as it does in description, the novel challenges these conceptual orders rather than taking one side or the other; it thus invites us to rethink the terrain of narrativity. -

ED311449.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 311 449 CS 212 093 AUTHOR Baron, Dennis TITLE Declining Grammar--and Other Essays on the English Vocabulary. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, Ill. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-1073-8 PUB DATE 89 NOTE :)31p. AVAILABLE FROM National Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Rd., Urbana, IL 61801 (Stock No. 10738-3020; $9.95 member, $12.95 nonmember). PUB TYPE Books (010) -- Viewpoints (120) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC10 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *English; Gr&mmar; Higher Education; *Language Attitudes; *Language Usage; *Lexicology; Linguistics; *Semantics; *Vocabulary IDENTIFIERS Words ABSTRACT This book contains 25 essays about English words, and how they are defined, valued, and discussed. The book is divided into four sections. The first section, "Language Lore," examines some of the myths and misconceptions that affect attitudes toward language--and towards English in particular. The second section, "Language Usage," examines some specific questions of meaning and usage. Section 3, "Language Trends," examines some controversial r trends in English vocabulary, and some developments too new to have received comment before. The fourth section, "Language Politics," treats several aspects of linguistic politics, from special attempts to deal with the ethnic, religious, or sex-specific elements of vocabulary to the broader issues of language both as a reflection of the public consciousness and the U.S. Constitution and as a refuge for the most private forms of expression. (MS) *********************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. *********************************************************************** "PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE THIS MATERIAL HAS BEEN GRANTED BY J. Maxwell TO THE EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES INFORMATION CENTER (ERIC)." U S. -

Forget Reaganreagan His Foreign Policy Was Right for His Time—Not Ours

Our Lousy Generals Immigration Reformed American Pravda Sex, Spies & the ’60s ANDREW J. BACEVICH WILLIAM W. CHIP RON UNZ CHRISTOPHER SANDFORD MAY/JUNE 2013 IDEAS OVER IDEOLOGY • PRINCIPLES OVER PARTY ForgetForget ReaganReagan His foreign policy was right for his time—not ours $9.99 US/Canada theamericanconservative.com Meet Pope Francis The Pope from the End of the Earth This lavishly illustrated volume by bestselling author Thomas J. Craughwell commemorates the election of Francis—first Pope from the New World—and explores in fascinating detail who he is and what his papacy will mean for the Church. • Forward by Cardinal Seán O’Malley. • Over 60 full-color photographs of Francis’s youth, priesthood and journey to Rome. • In-depth biography, from Francis’s birth and early years, to his mystical experience as a teen, to his ministry as priest and bishop with a heart for the poor and the unflagging courage to teach and defend the Faith. • Francis’s very first homilies as Pope. • Supplemental sections on Catholic beliefs, practices and traditions. $22.95 978-1-618-90136-1 • Hardcover • 176 pgs American Conservative Readers: Save $10 when you use coupon code TANGiftTAC at TANBooks.com. Special discount code expires 8/31/2013. Available at booksellers everywhere and at TANBooks.com e Publisher You Can Trust With Your Faith 58 THE AMERICAN CONSERVATIVE 1-800-437-5876MAY/JUNE 2013 Vol. 12, No. 3, May/June 2013 22 28 51 COVER STORY FRONT LINES ARTS & LETTERS 12 Reagan, Hawk or Dove? 7 Defense spending isn’t 40 The Generals: American The right foreign-policy lessons defense strength Military Command From to take from the 40th president WILLIAM S. -

Brilliant Creatures

A STUDY GUIDE BY PAULETTE GITTINS http://www.metromagazine.com.au ISBN: 978-1-74295-471-4 http://www.theeducationshop.com.au ‘They made us laugh, made us think, made us question, made us see Australia differently... are A two-part documentary By Director PAUL CLARKE and Executive Producers MARGIE BRYANT & ADAM KAY and Series Producer DAN GOLDBERG Written and presented by HOWARD JACOBSON SCREEN AUSTRALIA and 2014 © ATOM SCREEN EDUCATION THE ABC present a Serendipity and Mint Pictures production A STUDY GUIDE BY PAULETTE GITTINS 2 Introduction remarkable thing’ The story of the Australia they left in the sixties, and the impact they would have on the world stage is well worth reflecting on. Robert Hughes: firebrand art critic. Clive James: memoirist, broadcaster, poet. But why did they leave? What explains their spectacular success? Was it because they were Australian that they Barry Humphries: savage satirist. were able to conquer London and New York? And why does it matter so much to me? Germaine Greer: feminist, libertarian. asks our narrator. This is a deeply personal journey for Exiles from Australia, all of them. Howard Jacobson, an intrinsic character in this story. Aca- demic and Booker Prize winner, he reflects on his own ex- perience of Australia and how overwhelmed he was by the positive qualities he immediately sensed when he arrived ith these spare, impeccably chosen in this country. Why, he asks us, would Australians ever words, the voice-over of Howard Jacob- choose to exile themselves from such beauty and exhilara- son opens the BBC/ABC documentary tion? What were they sailing away to find? Brilliant Creatures and encapsulates the essence of four Australians who, having In wonderfully rich archive and musical sequences that Wsailed away from their native shores in the 1960’s, achieved reflect a fond ‘take’ on the era, director Paul Clarke has spectacular success in art criticism, literature, social cri- also juxtaposed interviews from past and present days. -

A Critical Analysis of Jean Paul Sartre's Existential Humanism with Particular Emphasis Upon His Concept of Freedom and Its Moral Implications

University of Windsor Scholarship at UWindsor Electronic Theses and Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, and Major Papers 1-1-1963 A critical analysis of Jean Paul Sartre's existential humanism with particular emphasis upon his concept of freedom and its moral implications. Joseph P. Leddy University of Windsor Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd Recommended Citation Leddy, Joseph P., "A critical analysis of Jean Paul Sartre's existential humanism with particular emphasis upon his concept of freedom and its moral implications." (1963). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 6331. https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd/6331 This online database contains the full-text of PhD dissertations and Masters’ theses of University of Windsor students from 1954 forward. These documents are made available for personal study and research purposes only, in accordance with the Canadian Copyright Act and the Creative Commons license—CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution, Non-Commercial, No Derivative Works). Under this license, works must always be attributed to the copyright holder (original author), cannot be used for any commercial purposes, and may not be altered. Any other use would require the permission of the copyright holder. Students may inquire about withdrawing their dissertation and/or thesis from this database. For additional inquiries, please contact the repository administrator via email ([email protected]) or by telephone at 519-253-3000ext. 3208. A CRITICAL ANALYSIS OF JEAN PAUL SARTRE'S EXISTENTIAL HUMANISM WITH PARTICULAR EMPHASIS UPON HIS CONCEPT OF FREEDOM AND ITS MORAL IMPLICATIONS A THESIS Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies through the Department of Philosophy in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts at Assumption University of Windsor by JOSEPH P. -

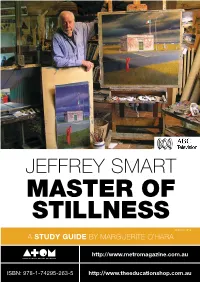

Jeffrey Smart Master of Stillness

JEFFREY SMART MASTER OF STILLNESS © ATOM 2012 A STUDY GUIDE BY MArguerite o’hARA http://www.metromagazine.com.au ISBN: 978-1-74295-263-5 http://www.theeducationshop.com.au I find it funny that perhaps in 100 years time, if people look at paintings done by the artists of this century, of our century, that the most ubiquitous things, like motor cars and television sets and telephones, don’t appear in any of the pictures. We should paint the things around us. Motor cars are very beautiful. I’m a great admirer of Giorgio Morandi; we all love Morandi, and he had all his props, his different bottles and his things. See, my props are petrol stations and trucks If a good painting comes off, it has a stillness, it has and it’s just the same a perfection, and that’s as great as anything that a thing. It’s a different musician or a poet can do. – Jeffrey Smart range of things. Introduction Jeffrey Smart Jeffrey Smart: Master of Stillness (Catherine Hunter, 2012) sheds light on the early influences of one of our greatest painters. Born in Adelaide in 1921, Smart’s early years were spent discovering the back lanes of the city’s inner suburbs. Now retired from painting, his last work Labyrinth (2011) evokes those memories. It is also a kind of arrival at the painting he was always chasing, never satisfied, hoping the next one on the easel would be the elusive masterpiece, the one that said it all. In this sense, Labyrinth brings a full stop to his career, and at the same time makes for a full, perpetual circle within his life.