Tamil Nadu Legislative Assembly Quinquennial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SS Ramasubbu

SS Ramasubbu https://www.indiamart.com/ss-ramasubbu/ MR. SS Ramasubbu MP (2009-2014) is from a veteran Congress Family .His father Late S.Sudalaimuthu Nadar, a freedom fighter, was a leading Congress personality in Nellai District. MR. SS Ramasubbu is involved in party function for more then ... About Us MR. SS Ramasubbu MP (2009-2014) is from a veteran Congress Family .His father Late S.Sudalaimuthu Nadar, a freedom fighter, was a leading Congress personality in Nellai District. MR. SS Ramasubbu is involved in party function for more then 32 years. He started his political career as district student congress secretary in the year 1972. During the year 1979 he had joined a Bank job. After 7 years of bank service, he resigned his Bank Job and became the full time politician in Congress party to serve the public. In the year 1989 Tamil Nadu Congress Committee took a noble decision to contest assembly election individually without the alliance of any Dravidian Party under the President ship of Sri. G.K.Mooppanar. Mr. S S Ramasubbu was selected to contest at Alangulam Constituency by the grace of our beloved leaders, Sri. Rajiv Gandhi and Sri. Moopanar Jee. It was an historical event that our esteemed leader Sri. Rajiv Gandhi introduced MR. S S Ramasubbu as contesting candidate amidst a very big gathering at Alangulam. MR. Ramasubbu had won the election by defeating the opponent Candidates Mr. Aladi Aruna and Karuppasamy Pandian who are considered to be the big guns in Dravidian Parties from Nellai District. BY appreciating his performance both in Assembly and among public, Congress high Command selected him for second time to contest in Assembly Election 1991. -

Tamil Nadu Government Gazette

© [Regd. No. TN/CCN/467/2009-11. GOVERNMENT OF TAMIL NADU [R. Dis. No. 197/2009. 2011 [Price: Rs. 17.60 Paise. TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY No. 15] CHENNAI, WEDNESDAY, APRIL 27, 2011 Chithirai 14, Thiruvalluvar Aandu–2042 Part VI—Section 4 Advertisements by private individuals and private institutions CONTENTS PRIVATE ADVERTISEMENTS Pages Change of Names .. 6791-834 Notice .. Nil NOTICE NO LEGAL RESPONSIBILITY IS ACCEPTED FOR THE PUBLICATION OF ADVERTISEMENTS REGARDING CHANGE OF NAME IN THE TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE. PERSONS NOTIFYING THE CHANGES WILL REMAIN SOLELY RESPONSIBLE FOR THE LEGAL CONSEQUENCES AND ALSO FOR ANY OTHER MISREPRESENTATION, ETC. (By Order) Director of Stationery and Printing. CHANGE OF NAMES My son, S. Vijay Aditya Muthu, born on 14th March 2009 I, B. Revathi, daughter of Thiru S.K. Bharathan, born on (native district: Chennai), residing at No. 134/A, G1, B-Block, 15th October 1978 (native district: Salem), residing at Y S Enclave, Arcot Road, Virugambakkam, Chennai-600 092, Old No. 4, New No. 7, 3rd E.M.M. Street, Chennimalai Road, shall henceforth be known as S. VIJAY ADITHYA MUTHU. Erode-638 001, shall henceforth be known as B. RENUKA. M. SRIRAMAN. B. REVATHI. Chennai, 18th April 2011. (Father.) Erode, 18th April 2011. I, Suguna Mohan Raam, wife of Thiru B.R. Mohan Ram, My son, R. Naveen, born on 19th June 1997 (native born on 14th February 1958 (native district: Chennai), residing district: Salem), residing at Old No. 13, New No. 20, Adhi at No. 18/6, Sastha Nagar, Villivakkam, Chennai-600 049, Raman Street, Shevapet, Salem-636 002, shall henceforth shall henceforth be known as SUGUNA MOHAN RAM. -

Court No.2 Hon'ble Mr.Justice M.Jaichandren Hon'ble Mr

COURT NO.2 HON'BLE MR.JUSTICE M.JAICHANDREN HON'BLE MR.JUSTICE S.NAGAMUTHU AND HON'BLE MR.JUSTICE M.VENUGOPAL BEFORE THE MADURAI BENCH OF MADRAS HIGH COURT TORDERS TO BE DELIVERED ON FRIDAY THE 29TH DAY OF NOVEMBER 2013 AT 10.30 A.M. ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ------ FOR ORDERS ~~~~~~~~~~ WRIT PETITION RELATING TO THE QUESTION AS TO WHETHER SERVICE REGULARIZATION ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ WILL BE FROM THE DATE OF INITIAL APPOINTMENT (OR) FROM THE DATE OF COMPLETION ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ OF 3 YEARS OF SERVICE ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ 1. WP(MD).1083/2012 M/S. S. ARUNACHALAM SPL. G.P. TAKES NOTICE (Service) R. MURUGAN FOR R1 AND R2 MR.G.R.SWAMINATHAN FOR R3 (III SET NOT FILED) 2. WA(MD).555/2010 M/S.M.SURESH KUMAR R1-THE STATE OF TAMIL NADU M/S.R.MURALI REP BY ITS SECRETARY DEPT. OF MUNICIPAL ADMINISTRATION AND WATER SUPPLY - CHENNAI R2 - THE COMMISSIONER NAGERCOIL MUNICIPALITY Fix an early date MP(MD).1/2013 M/S.M.SURESH KUMAR M/S.R.MURALI ***************( Concluded )*************** COURT NO.2 HON'BLE MR.JUSTICE M.JAICHANDREN HON'BLE MR.JUSTICE M.VENUGOPAL AND HON'BLE MR.JUSTICE T.RAJA BEFORE THE MADURAI BENCH OF MADRAS HIGH COURT TORDERS TO BE DELIVERED ON FRIDAY THE 29TH DAY OF NOVEMBER 2013 (AFTER FULL BENCH SITTINGS OF THE HON'BLE MR.JUSTICE M.JAICHANDREN, THE HON'BLE MR.JUSTICE S.NAGAMUTHU AND THE HON'BLE MR.JUSTICE M.VENUGOPAL) ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ------ FOR ORDERS ~~~~~~~~~~ WRIT PETITION RELATING TO THE QUESTION AS TO WHETHER EQUIVELANCE CERTIFICATE ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ WILL HAVE PROSPECTIVE EFFECT ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ 1. WP(MD).16181/2012 M/S.D.SHANMUGARAJA SETHUPATHI SPL GP(W) (Service) B.VELAYUTHAM 2. -

TN-Service-Manual-VOL-2.Pdf

TAMIL NADU SERVICES MANUAL VOLUME II STATE SERVICES ______ SPECIAL RULES THIS VOLUME CONTAINS THE SPECIAL RULES RELATING TO THE STATE SERVICES (SECTIONS 1 to 51 OF PART III A) (Incorporates amendments issued upto 31st August 2012) © GOVERNMENT OF TAMIL NADU 2016 PRINTED BY THE DIRECTOR OF STATIONERY AND PRINTING, CHENNAI, ON BEHALF OF THE GOVERNMENT OF TAMIL NADU 2016 TAMIL NADU SERVICES MANUAL, VOLUME II PREFACE This Tamil Nadu Services Manual, Volume II contains various Special Rules pertaining to State Services. This Volume was earlier released in the year 1969. Over the years, several new services were framed and consequently new rules introduced. So, this Department considered it absolute necessary to update the Statutory Manual by constituting a Committee with experts who were senior retired officials of the Personnel and Administrative Reforms Department and for them to be assisted by key officials of the Department. After a massive effort involving all Departments, the Personnel and Administrative Reforms (S) Department has now updated the Manual with the Assistance of Committee Members, Officers of this Department, all other Departments of Secretariat and the respective Heads of Department. Taking into consideration the massive contribution and involvement of the team in Personnel and Administrative Reforms Department that made this possible, it is fitting to place their names on record in appreciation of the good work done. The above Volume is also available in the Tamil Nadu Government Website in electronic form and will be updated online as and when changes or alterations happen. Fort. St. George, P.W.C. DAVIDAR, I.A.S., Secretariat, Principal Secretary to Government Chennai-600 009. -

Appendix Bibliography

Cover Page The handle http://hdl.handle.net/1887/71028 holds various files of this Leiden University dissertation. Author: Wibulsilp, P. Title: Nawabi Karnatak: Muhammad Ali Khan in the Making of a Mughal Successor State in Pre-colonial South India, 1749-1795 Issue Date: 2019-04-09 Appendix This appendix provides selective lists of some primary sources related to late-eighteenth- century Karnatak that—due to limitations of time—have not been used in this thesis but which are useful for further research. Persian Sources Published sources: 1. The Ruqaat-i Walajahi (Epistles of the Walajah), edited by T. Chandrasekaran (Madras, 1958). This is a large collection of approximately a thousand letters produced during the period 1774-1775, which were published in 1958. Many of these documents were written by the Nawab’s revenue collectors and officers, while others were replies and orders issued by the Nawab related to day-to-day administrative matters such as land grants, taxes, agricultural activity, public welfare, art and crafts, and military organization. 2. The Nishan-i Hydari (Hydari Signs), by Mir Husain Ali Khan Kirman, written in 1802. This is actually a history of Hyder Ali and Tipu Sultan, the rulers of Mysore. However, it also recounts relations between the Mysore ruler(s) and Nawab Muhammad Ali. It was translated into English by Colonel William Miles and published for the first time in 1864. Unpublished manuscripts: 1. The Tahrik al-Shifah bi-Ausaf Walajah (Mobilising Cure in the Description/ Characteristics of Walajah [?]) , by Amir al-Umara (the Nawab’s second son), written ca. -

THE NEW CAMBRIDGE HISTORY of INDIA Indian Society and The

THE NEW CAMBRIDGE HISTORY OF INDIA Indian society and the making of the British Empire Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008 THE NEW CAMBRIDGE HISTORY OF INDIA General editor GORDON JOHNSON President of Wolfson College, and Director, Centre of South Asian Studies, University of Cambridge Associate editors CA. BAYLY Vere Harmsworth Professor of Imperial and Naval History, University of Cambridge, and Fellow of St Catharine's College and JOHN F. RICHARDS Professor of History, Duke University Although the original Cambridge History of India, published between 1922. and 1937, did much to formulate a chronology for Indian history and de- scribe the administrative structures of government in India, it has inevitably been overtaken by the mass of new research published over the last fifty years. Designed to take full account of recent scholarship and changing concep- tions of South Asia's historical development, The New Cambridge History of India will be published as a series of short, self-contained volumes, each dealing with a separate theme and written by a single person. Within an overall four-part structure, thirty-one complementary volumes in uniform format will be published. As before, each will conclude with a substantial bib- liographical essay designed to lead non-specialists further into the literature. The four parts planned are as follows: I The Mughals and their contemporaries II Indian states and the transition to colonialism III The Indian Empire and the beginnings of modern society IV The evolution of contemporary South Asia A list of individual titles in preparation will be found at the end of the volume. -

Nature and Scope of Archives a Study

Historical Research Letter www.iiste.org ISSN 2224-3178 (Paper) ISSN 2225-0964 (Online) Vol 18, 2015 Nature and Scope of Archives a Study M.SAMPATHKUMAR PhD,Research Scholar, P.G.Research Department of History, Arignar Anna Government Arts College, Musiri- 621 211 INTRODUCTION The word ‘Archives’ is commonly used for denoting the records and other documents as well as the institution which holds the records. Archives is a store house of information concerning all factors of human life. Since it is the emporium of all the activities of mankind from time immemorial to the present, it depicts the customs, conventions and usage of people. Historians and writers are fully dependent upon the documents and records of the archives for portraits of the life and activities of their predecessors. The British Government is popularly called the paper Government because they recorded all matters on paper and preserved them for future reference. Their preservation of records in India and England benefited the histories and gave new enlightment to the subject on Indian study. They paid special attention for preserving their records by establishing actives both in national and regional level in the western model. The increasing mass of record and a better appreciation of their value as public Archives led the Government to establish an independent Record Department in 1909. Therefore, the Madras Record office was built in Egmore area of Chennai. This neo – Gothic building (Indo – British Architecture) was planned with open spaces for future expansion and constructed to provide maximum protection to the records. It is still occupied by the Tamil Nadu Archives today, after India’s Independence, the institution was named as Madras State Archives in 1969. -

M.A. HISTORY (SEMESTER) (CBCS) REVISED SYLLABUS (Effect from 2018 Onwards) REGULATIONS and SCHEME of EXAMINATIONS 1

Placed at the meeting of Academic Council held on 26.03.2018 APPENDIX - CB MADURAI KAMARAJ UNIVERSITY (University with Potential for Excellence) M.A. HISTORY (SEMESTER) (CBCS) REVISED SYLLABUS (Effect from 2018 onwards) REGULATIONS AND SCHEME OF EXAMINATIONS 1. Introduction of the Programme: The M.A. History Programme has been designed in accordance with the National Education Policy and as per the guidelines given by the Tamil Nadu State Council for Higher Education that emphasise on introduction of innovative and socially relevant courses at the Post Graduate level. It is expected to be highly beneficial to the student community. This Programme introduces new ideas slowly and carefully in such manner so as to give the students a good institutive feeling for the subject and develops an interest in the subject to pursue their studies further. The Syllabus is restricted to suit the needs of the time and to enhance employability of the students without compromising the intrinsic value of studying the past. It would also prove to be a great asset for those preparing for NET, SET and other competitive examinations. 2. Eligibility for admission: Candidates who have a B.A. Degree in History from any recognised University are eligible to join this Programme. The duration of the Programme shall be two academic years comprising four semesters in each academic year. Medium of Instructions: English 3. Objectives of the Programme: The main objective of the course is to provide a detailed study of the history of India and Tamil Nadu as well as substantial surveys of the history of other important countries of the world. -

July 2017 Newsletter

I nternal Q uality A ssurance C ompliance e - Newsletter July 2017 Vision Mission To be a Centre of Excellence of To produce Technically International repute in Competent, Socially committed Education and Research. Technocrats and Administrators through Quality Education and Research. e Newsletter July 2017 INDEX School of Agriculture and Processing Sciences (SoAPS) ................................ ......... 4 School of Bio and Chemical Engineering (SBCE) ................................ ................... 4 School of Environmental and Construction Technology (SECT) ........................... 5 School of Electronics and Electrical Technology (SEET) ................................ ........ 7 School of Computing (SoC) ................................ ................................ ...................... 11 School of Automotive and Mechanical Engineering (SAME) ................................ 14 Kalasalingam Business School (KBS) ................................ ................................ .... 17 School of Advanced Sciences (SAS) ................................ ................................ ....... 20 School of Liberal Arts and Education (SLATE) ................................ .................... 21 Speech and Hearing Impaired persons (SHIP) ................................ ...................... 22 Centres of Excellence ................................ ................................ ............................... 23 Centre for Competitive Examinations Extra - Curricular Activities Research Publications ............................... -

Tamil Nadu Government Gazette

© [Regd. No. TN/CCN/467/2012-14. GOVERNMENT OF TAMIL NADU [R. Dis. No. 197/2009. 2015 [Price: Rs. 36.80 Paise. TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY No. 25] CHENNAI, WEDNESDAY, JUNE 24, 2015 Aani 9, Manmadha, Thiruvalluvar Aandu – 2046 Part VI—Section 4 Advertisements by private individuals and private institutions CONTENTS PRIVATE ADVERTISEMENTS Pages. Change of Names .. 1859-1950 Notice .. 1950 NOTICE NO LEGAL RESPONSIBILITY IS ACCEPTED FOR THE PUBLICATION OF ADVERTISEMENTS REGARDING CHANGE OF NAME IN THE TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE. PERSONS NOTIFYING THE CHANGES WILL REMAIN SOLELY RESPONSIBLE FOR THE LEGAL CONSEQUENCES AND ALSO FOR ANY OTHER MISREPRESENTATION, ETC. (By Order) Director of Stationery and Printing. CHANGE OF NAMES 27046. I, N. Rudramoorthy, son of Thiru C. Natarajan, 27049. My son, V. Vicky, born on 10th June 1998 born on 5th June 1969 (native district: Dindigul), residing at (native district: Madurai), residing at No. 463, East Street, Old No. 3A/12, New No. 4/3/13, Balaji Nagar, Neruji Karumpalai, Madurai-625 020, shall henceforth be Nagar Virivakkam, Dindigul-624 001, shall henceforth be known as V. VIGNESH. known as N. RUTHRA MOORTTHY. º. «õ½. N. RUDRAMOORTHY. Madurai, 15th June 2015. (Father.) Dindigul, 15th June 2015. 27050. I, G. Sundaram, son of Thiru Gurusamy, 27047. My son, R. Justin, son of Thiru C. Ramakrishnan, born on 14th June 1962 (native district: Madurai), born on 15th July 2009 (native district: Ramanathapuram), residing at No. 2/88, Veeravanour, Paramakudi Taluk, residing at No. 1/79, West Street, Vandapuli, Peraiyur Ramanathapuram-623 502, shall henceforth be known Taluk, Madurai-625 705, shall henceforth be as R. -

Higher Education Department

HIGHER EDUCATION DEPARTMENT POLICY NOTE 2013 – 2014 DEMAND NO. 20 P. PALANIAPPAN MINISTER OF HIGHER EDUCATION © Government of Tamil Nadu 2013 CONTENTS Sl. Headings Pages No. 1. Introduction 1- 22 2. Collegiate Education 23-32 3. Technical Education 33-44 4. Universities 45-111 5. Tamil Nadu Archives 112-114 6. Tamil Nadu State Council 115-121 for Higher Education 7. Tamil Nadu State Council 122-123 for Technical Education 8. Science City 124-127 9. Tamil Nadu Science and 128-132 Technology Centre 10. Tamil Nadu State Council 133-143 for Science and Technology 11. Tamil Nadu State Urdu 144-145 Academy POLICY NOTE DEMAND NO.20 - HIGHER EDUCATION 2013–2014 INTRODUCTION “Without a body of sufficiently skilled and balanced workforce, no economy can hope to develop to its potential. Vision 2023, under its Education and Skills mission, aims to establish a robust human resources pipeline.” Hon’ble Chief Minister of Tamil Nadu Vision Tamil Nadu 2023 1.1 Tamil Nadu is a frontline State in several fields viz., Education, Health, Industries, Social Welfare etc., thanks to the dynamic guidance of our Hon’ble Chief Minister. The Higher Education sector in Tamil Nadu is moving at an accelerated pace to meet the demands of the century, in terms of research and development. In keeping with the vision of our Hon’ble Chief Minister to make Tamil Nadu, “the innovation hub and the knowledge capital of India” and “to set Tamil Nadu in a high growth trajectory” Higher Education Department is all set to ensure access, equity and world class standards for our youth. -

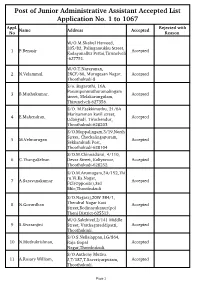

Post of Junior Administrative Assistant Accepted List Application No. 1 to 1067 Appl

Post of Junior Administrative Assistant Accepted List Application No. 1 to 1067 Appl. Rejected with Name Address Accepted No Reason W/O.M.Shahul Hameed, 205/82, Palingamukku Street, 1 P.Benasir Accepted Kadayanallur Pettai,Tirunelveli -627751. W/O.T.Narayanan, 2 N.Velammal. 2BCE/66, Murugesan Nagar, Accepted Thoothukudi-8 S/o. Bagavathi, 16A, Pasumponmuthuramalingam 3 B.Muthukumar, Accepted street, Melakarungulam, Thirunelveli-627356. S/O. M.Esakkimuthu, 21/6A Mariyamman kovil street, 4 E.Mahendran, Accepted Udangudi, Tiruchendur, Thoothukudi-628203 S/O.Muppalingam,3/19,North Street, Chockalingapuram, 5 M.Velmurugan Accepted Sekkarakudi Post, Thoothukudi-628104 S/O.M.Chinnadurai, 4/110, 6 C.ThangaSelvan Devar Street, Kaliyavoor, Accepted Thoothukudi-628252. S/O.M.Arumugam,3A/152,Thi ru.Vi.Ka.Nagar, 7 A.Saravanakumar Accepted FCI(Opposite),3rd Mile,Thoothukudi S/O.Nagaraj,20W 3B4/1, 8 N.Govardhan Thendral Nagar East Accepted Street,Bodinayakanur(po) Theni District-625513. W/O.Sakthivel,2/141 Middle 9 S.Sivaranjini Street, Varthagareddipatti, Accepted Thoothukudi. S/O.S.Nellaiappan,1G/864, 10 N.Muthukrishnan, Raja Gopal Accepted Nagar,Thoothukudi. S/O.Anthony Muthu. 11 A.Rosary William, J,7/187,T.Saveriyarpuram, Accepted Thoothukudi. Page 1 S/O.S.Seenivasagam, 7/36,Colony Street, 12 S.Premkumar, k.Velayuthapurm, Accepted Kurukkuchalai Post,Ottapidaram Taluk,Thoothukudi. D/O.Pandiyarajan,1/73,Vaniya 13 P.Gunavathy, vallam,NainarKoil Accepted Post,Paramakudi,Ramanathap uram District. D/O.K.Vilvanathan, 14 K.V.Maharasi Malathi 25/29,Toovipuram West Street Accepted No 4,Thoothukudi. S/O.P.Ragunathan, 51,Chellappa Nagar, 15 G.R.Boobalan, Madeswran Koil Accepted Street,Gobichettipalayam Post,Erode District.