Planetary Chaos and the (In) Stability of Hungaria Asteroids

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

174 Minor Planet Bulletin 47 (2020) DETERMINING the ROTATIONAL

174 DETERMINING THE ROTATIONAL PERIODS AND LIGHTCURVES OF MAIN BELT ASTEROIDS Shandi Groezinger Kent Montgomery Texas A&M University-Commerce P.O. Box 3011 Commerce, TX 75429-3011 [email protected] (Received: 2020 Feb 21 Revised: 2020 March 20) Lightcurves and rotational periods are presented for six main-belt asteroids. The rotational periods determined are 970 Primula (2.777 ± 0.001 h), 1103 Sequoia (3.1125 ± 0.0004 h), 1160 Illyria (4.103 ± 0.002 h), 1188 Gothlandia (3.52 ± 0.05 h), 1831 Nicholson (3.215 ± 0.004 h) and (11230) 1999 JV57 (7.090 ± 0.003 h). The purpose of this research was to create lightcurves and determine the rotational periods of six asteroids: 970 Primula, 1103 Sequoia, 1160 Illyria, 1188 Gothlandia, 1831 Nicholson and (11230) 1999 JV57. Asteroids were selected for this study from a website that catalogues all known asteroids (CALL). For an asteroid to be chosen in this study, it has to meet the requirements of brightness, declination, and opposition date. For optimum signal to noise ratio (SNR), asteroids of apparent magnitude of 16 or lower were chosen. Asteroids with positive declinations were chosen due to using telescopes located in the northern hemisphere. The data for all the asteroids was typically taken within two weeks from their opposition dates. This would ensure a maximum number of images each night. Asteroid 970 Primula was discovered by Reinmuth, K. at Heidelberg in 1921. This asteroid has an orbital eccentricity of 0.2715 and a semi-major axis of 2.5599 AU (JPL). Asteroid 1103 Sequoia was discovered in 1928 by Baade, W. -

Multiple Asteroid Systems: Dimensions and Thermal Properties from Spitzer Space Telescope and Ground-Based Observations*

Multiple Asteroid Systems: Dimensions and Thermal Properties from Spitzer Space Telescope and Ground-Based Observations* F. Marchisa,g, J.E. Enriqueza, J. P. Emeryb, M. Muellerc, M. Baeka, J. Pollockd, M. Assafine, R. Vieira Martinsf, J. Berthierg, F. Vachierg, D. P. Cruikshankh, L. Limi, D. Reichartj, K. Ivarsenj, J. Haislipj, A. LaCluyzej a. Carl Sagan Center, SETI Institute, 189 Bernardo Ave., Mountain View, CA 94043, USA. b. Earth and Planetary Sciences, University of Tennessee 306 Earth and Planetary Sciences Building Knoxville, TN 37996-1410 c. SRON, Netherlands Institute for Space Research, Low Energy Astrophysics, Postbus 800, 9700 AV Groningen, Netherlands d. Appalachian State University, Department of Physics and Astronomy, 231 CAP Building, Boone, NC 28608, USA e. Observatorio do Valongo/UFRJ, Ladeira Pedro Antonio 43, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil f. Observatório Nacional/MCT, R. General José Cristino 77, CEP 20921-400 Rio de Janeiro - RJ, Brazil. g. Institut de mécanique céleste et de calcul des éphémérides, Observatoire de Paris, Avenue Denfert-Rochereau, 75014 Paris, France h. NASA Ames Research Center, Mail Stop 245-6, Moffett Field, CA 94035-1000, USA i. NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, MD 20771, United States j. Physics and Astronomy Department, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC 27514, U.S.A * Based in part on observations collected at the European Southern Observatory, Chile Programs Numbers 70.C-0543 and ID 72.C-0753 Corresponding author: Franck Marchis Carl Sagan Center SETI Institute 189 Bernardo Ave. Mountain View CA 94043 USA [email protected] Abstract: We collected mid-IR spectra from 5.2 to 38 µm using the Spitzer Space Telescope Infrared Spectrograph of 28 asteroids representative of all established types of binary groups. -

The Minor Planet Bulletin

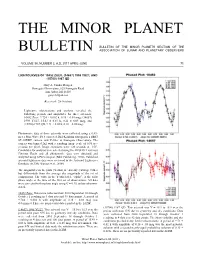

THE MINOR PLANET BULLETIN OF THE MINOR PLANETS SECTION OF THE BULLETIN ASSOCIATION OF LUNAR AND PLANETARY OBSERVERS VOLUME 36, NUMBER 3, A.D. 2009 JULY-SEPTEMBER 77. PHOTOMETRIC MEASUREMENTS OF 343 OSTARA Our data can be obtained from http://www.uwec.edu/physics/ AND OTHER ASTEROIDS AT HOBBS OBSERVATORY asteroid/. Lyle Ford, George Stecher, Kayla Lorenzen, and Cole Cook Acknowledgements Department of Physics and Astronomy University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire We thank the Theodore Dunham Fund for Astrophysics, the Eau Claire, WI 54702-4004 National Science Foundation (award number 0519006), the [email protected] University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire Office of Research and Sponsored Programs, and the University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire (Received: 2009 Feb 11) Blugold Fellow and McNair programs for financial support. References We observed 343 Ostara on 2008 October 4 and obtained R and V standard magnitudes. The period was Binzel, R.P. (1987). “A Photoelectric Survey of 130 Asteroids”, found to be significantly greater than the previously Icarus 72, 135-208. reported value of 6.42 hours. Measurements of 2660 Wasserman and (17010) 1999 CQ72 made on 2008 Stecher, G.J., Ford, L.A., and Elbert, J.D. (1999). “Equipping a March 25 are also reported. 0.6 Meter Alt-Azimuth Telescope for Photometry”, IAPPP Comm, 76, 68-74. We made R band and V band photometric measurements of 343 Warner, B.D. (2006). A Practical Guide to Lightcurve Photometry Ostara on 2008 October 4 using the 0.6 m “Air Force” Telescope and Analysis. Springer, New York, NY. located at Hobbs Observatory (MPC code 750) near Fall Creek, Wisconsin. -

The Minor Planet Bulletin and How the Situation Has Gone from One Mt Tarana Observatory of Trying to Fill Pages to One of Fitting Everything In

THE MINOR PLANET BULLETIN OF THE MINOR PLANETS SECTION OF THE BULLETIN ASSOCIATION OF LUNAR AND PLANETARY OBSERVERS VOLUME 33, NUMBER 2, A.D. 2006 APRIL-JUNE 29. PHOTOMETRY OF ASTEROIDS 133 CYRENE, adjusted up or down to line up with the V-band data). The near- 454 MATHESIS, 477 ITALIA, AND 2264 SABRINA perfect overlay of V- and R-band data show no evidence of color change as the asteroid rotates. This result replicates the lightcurve Robert K. Buchheim period reported by Harris et al. (1984), and matches the period and Altimira Observatory lightcurve shape reported by Behrend (2005) at his website. 18 Altimira, Coto de Caza, CA 92679 USA [email protected] (Received: 4 November Revised: 21 November) Photometric studies of asteroids 133 Cyrene, 454 Mathesis, 477 Italia and 2264 Sabrina are reported. The lightcurve period for Cyrene of 12.707±0.015 h (with amplitude 0.22 mag) confirms prior studies. The lightcurve period of 8.37784±0.00003 h (amplitude 0.32 mag) for Mathesis differs from previous studies. For Italia, color indices (B-V)=0.87±0.07, (V-R)=0.48±0.05, and phase curve parameters H=10.4, G=0.15 have been determined. For Sabrina, this study provides the first reported lightcurve period 43.41±0.02 h, with 0.30 mag amplitude. Altimira Observatory, located in southern California, is equipped with a 0.28-m Schmidt-Cassegrain telescope (Celestron NexStar- 454 Mathesis. DiMartino et al. (1994) reported a rotation period of 11 operating at F/6.3), and CCD imager (ST-8XE NABG, with 7.075 h with amplitude 0.28 mag for this asteroid, based on two Johnson-Cousins filters). -

Für Astronomie Nr

für Astronomie Nr. 28 Zeitschrift der Vereinigung der Sternfreunde e.V. / VdS DAS WELTALL Orionnebel DU LEBST DARIN – ENTDECKE ES! Computerastronomie Internationales Jahr der Astronomie INTERNATIONALES ISSN 1615 - 0880 www.vds-astro.de I/ 2009 ASTRONOMIEJAHR [email protected] • www.astro-shop.com Tel.: 040/5114348 • Fax: 040/5114594 Eiffestr. 426 • 20537 Hamburg Astroart 4.0 The Night Sky Observer´s Guide Photoshop Astronomy Die aktuellste Version Dieses hilfreiche Werk Der Autor arbeitet seit fast 10 Jahren mit Photo- des bekannten Bildbe- dient der erfolg- shop, um seine Astrofotos zu bearbeiten. Die arbeitungspro- reichen Vorbereitung dabei gemachten Erfahrungen hat er in diesem grammes gibt es jetzt einer abwechslungs- speziell auf die Bedürfnisse des Amateurastro- mit interessanten reichen Deep-Sky- nomen zugeschnitte- neuen Funktionen. Nacht. Sortiert nach nen Buch gesammelt. Moderne Dateifor- Sternbildern des Die behandelten The- men sind unter ande- mate wie DSLR-RAW Sommer- und Win- rem: die technische werden unterstützt, terhimmels nden Ausstattung, Farbma- Bilder können sich detaillierte NEU nagement, Histo- durch automa- Beschreibungen Südhimmel gramme, Maskie- 3. Band tische Sternfelderken- zu hunderten rungstechniken, nung direkt überlagert werden, was die Bild- Galaxien, Nebeln, Oenen Stern- und Addition mehrerer feldrotation vernachlässigbar macht. Auch die Kugelhaufen. Der Teleskopanblick jedes Bilder, Korrektur von Bearbeitung von Farbbildern wurde erweitert. Objekts ist beschrieben und mit einem Hin- Vignettierungen, Besonderes Augenmerk liegt auf der Erken- weis bezüglich der verwendeten Optik verse- Farbhalos, Deformationen oder nung und Behandlung von Pixelfehlern der hen. 2 Bände mit insgesamt 446 Fotos, 827 überbelichteten Sternen, LRGB und vieles Aufnahme-Chips. Zeichnungen, 143 Tabellen und 431 Sternkar- mehr. Auf der beigefügten DVD benden sich 90 alle im Buch besprochenen und verwendeten Update ten. -

1 Rotation Periods of Binary Asteroids with Large Separations

Rotation Periods of Binary Asteroids with Large Separations – Confronting the Escaping Ejecta Binaries Model with Observations a,b,* b a D. Polishook , N. Brosch , D. Prialnik a Department of Geophysics and Planetary Sciences, Tel-Aviv University, Israel. b The Wise Observatory and the School of Physics and Astronomy, Tel-Aviv University, Israel. * Corresponding author: David Polishook, [email protected] Abstract Durda et al. (2004), using numerical models, suggested that binary asteroids with large separation, called Escaping Ejecta Binaries (EEBs), can be created by fragments ejected from a disruptive impact event. It is thought that six binary asteroids recently discovered might be EEBs because of the high separation between their components (~100 > a/Rp > ~20). However, the rotation periods of four out of the six objects measured by our group and others and presented here show that these suspected EEBs have fast rotation rates of 2.5 to 4 hours. Because of the small size of the components of these binary asteroids, linked with this fast spinning, we conclude that the rotational-fission mechanism, which is a result of the thermal YORP effect, is the most likely formation scenario. Moreover, scaling the YORP effect for these objects shows that its timescale is shorter than the estimated ages of the three relevant Hirayama families hosting these binary asteroids. Therefore, only the largest (D~19 km) suspected asteroid, (317) Roxane , could be, in fact, the only known EEB. In addition, our results confirm the triple nature of (3749) Balam by measuring mutual events on its lightcurve that match the orbital period of a nearby satellite in addition to its distant companion. -

Michael P. Lucas and Joshua P. Emery

Surface Mineralogy of Mars-Crossing Asteroid 1747 Wright: Analogous to the H Chondrites Michael P. Lucas1 and Joshua P. Emery1 (1) Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, University of Tennessee, 1412 Circle Drive, Knoxville, TN 37996, [email protected] Introduction Mars-Crosser 1747 Wright Mineral Abundance and Composition Figure 6. – 1747 Wright and Asteroid dynamical work has suggested that differentiated • Previously classified in visible-light spectral three more asteroids asteroids, precursors of metallic (core) and olivine-rich (mantle) interior to the main-belt fragments may have formed in the terrestrial planet region and are surveys as an A-type indicated on the band-band now interlopers to the inner main-belt [1]. Furthermore, recent work [3,6], Sl-type [5], or an plot from [15]. 1747 Wright has suggested that the Hungaria asteroids are the survivors of an Ld-type [6] plots within the field of extended and now largely extinct portion of the asteroid belt that • We found 1747 Wright orthopyroxene (black diamonds), while 1509 existed between 1.7 and 2.1 AU early in solar system history [2] to be a Sw-type (Bus- DeMeo extended Esclangona appears to be (Figure 1). The mineralogy of these relatively close objects hold more clinopyroxene (gray important clues to the dynamical evolution of the inner-Solar System. taxonomy) squares) rich. In particular, a key aspect of asteroid mineralogy is the abundance • Presence of Band I and composition of olivine and pyroxene, which can reveal details near 0.90 µm and regarding the degree (or lack) of igneous differentiation. Figure 3. – VISNIR spectrum of 1747 Wright Band II near 1.9 µm obtained with the SpeX instrument on the NASA Figure 7. -

Symposium on Telescope Science

Proceedings for the 26th Annual Conference of the Society for Astronomical Sciences Symposium on Telescope Science Editors: Brian D. Warner Jerry Foote David A. Kenyon Dale Mais May 22-24, 2007 Northwoods Resort, Big Bear Lake, CA Reprints of Papers Distribution of reprints of papers by any author of a given paper, either before or after the publication of the proceedings is allowed under the following guidelines. 1. The copyright remains with the author(s). 2. Under no circumstances may anyone other than the author(s) of a paper distribute a reprint without the express written permission of all author(s) of the paper. 3. Limited excerpts may be used in a review of the reprint as long as the inclusion of the excerpts is NOT used to make or imply an endorsement by the Society for Astronomical Sciences of any product or service. Notice The preceding “Reprint of Papers” supersedes the one that appeared in the original print version Disclaimer The acceptance of a paper for the SAS proceedings can not be used to imply or infer an endorsement by the Society for Astronomical Sciences of any product, service, or method mentioned in the paper. Published by the Society for Astronomical Sciences, Inc. First printed: May 2007 ISBN: 0-9714693-6-9 Table of Contents Table of Contents PREFACE 7 CONFERENCE SPONSORS 9 Submitted Papers THE OLIN EGGEN PROJECT ARNE HENDEN 13 AMATEUR AND PROFESSIONAL ASTRONOMER COLLABORATION EXOPLANET RESEARCH PROGRAMS AND TECHNIQUES RON BISSINGER 17 EXOPLANET OBSERVING TIPS BRUCE L. GARY 23 STUDY OF CEPHEID VARIABLES AS A JOINT SPECTROSCOPY PROJECT THOMAS C. -

The Minor Planet Bulletin, Alan W

THE MINOR PLANET BULLETIN OF THE MINOR PLANETS SECTION OF THE BULLETIN ASSOCIATION OF LUNAR AND PLANETARY OBSERVERS VOLUME 42, NUMBER 2, A.D. 2015 APRIL-JUNE 89. ASTEROID LIGHTCURVE ANALYSIS AT THE OAKLEY SOUTHERN SKY OBSERVATORY: 2014 SEPTEMBER Lucas Bohn, Brianna Hibbler, Gregory Stein, Richard Ditteon Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology, CM 171 5500 Wabash Avenue, Terre Haute, IN 47803, USA [email protected] (Received: 24 November) Photometric data were collected over the course of seven nights in 2014 September for eight asteroids: 1334 Lundmarka, 1904 Massevitch, 2571 Geisei, 2699 Kalinin, 3197 Weissman, 7837 Mutsumi, 14927 Satoshi, and (29769) 1999 CE28. Eight asteroids were remotely observed from the Oakley Southern Sky Observatory in New South Wales, Australia. The observations were made on 2014 September 12-14, 16-19 using a 0.50-m f/8.3 Ritchey-Chretien optical tube assembly on a Paramount ME mount and SBIG STX-16803 CCD camera, binned 3x3, with a luminance filter. Exposure times ranged from 90 to 180 sec depending on the magnitude of the target. The resulting image scale was 1.34 arcseconds per pixel. Raw images were processed in MaxIm DL 6 using twilight flats, bias, and dark frames. MPO Canopus was used to measure the processed images and produce lightcurves. In order to maximize the potential for data collection, target asteroids were selected based upon their position in the sky approximately one hour after sunset. Only asteroids with no previously published results were targeted. Lightcurves were produced for 1334 Lundmarka, 1904 Massevitch, 2571 Geisei, 3197 Weissman, and (29769) 1999 CE28. -

The Minor Planet Bulletin

THE MINOR PLANET BULLETIN OF THE MINOR PLANETS SECTION OF THE BULLETIN ASSOCIATION OF LUNAR AND PLANETARY OBSERVERS VOLUME 38, NUMBER 2, A.D. 2011 APRIL-JUNE 71. LIGHTCURVES OF 10452 ZUEV, (14657) 1998 YU27, AND (15700) 1987 QD Gary A. Vander Haagen Stonegate Observatory, 825 Stonegate Road Ann Arbor, MI 48103 [email protected] (Received: 28 October) Lightcurve observations and analysis revealed the following periods and amplitudes for three asteroids: 10452 Zuev, 9.724 ± 0.002 h, 0.38 ± 0.03 mag; (14657) 1998 YU27, 15.43 ± 0.03 h, 0.21 ± 0.05 mag; and (15700) 1987 QD, 9.71 ± 0.02 h, 0.16 ± 0.05 mag. Photometric data of three asteroids were collected using a 0.43- meter PlaneWave f/6.8 corrected Dall-Kirkham astrograph, a SBIG ST-10XME camera, and V-filter at Stonegate Observatory. The camera was binned 2x2 with a resulting image scale of 0.95 arc- seconds per pixel. Image exposures were 120 seconds at –15C. Candidates for analysis were selected using the MPO2011 Asteroid Viewing Guide and all photometric data were obtained and analyzed using MPO Canopus (Bdw Publishing, 2010). Published asteroid lightcurve data were reviewed in the Asteroid Lightcurve Database (LCDB; Warner et al., 2009). The magnitudes in the plots (Y-axis) are not sky (catalog) values but differentials from the average sky magnitude of the set of comparisons. The value in the Y-axis label, “alpha”, is the solar phase angle at the time of the first set of observations. All data were corrected to this phase angle using G = 0.15, unless otherwise stated. -

Multiple Asteroid Systems: Dimensions and Thermal Properties from Spitzer Space Telescope and Ground-Based Observations Q ⇑ F

Icarus 221 (2012) 1130–1161 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Icarus journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/icarus Multiple asteroid systems: Dimensions and thermal properties from Spitzer Space Telescope and ground-based observations q ⇑ F. Marchis a,g, , J.E. Enriquez a, J.P. Emery b, M. Mueller c, M. Baek a, J. Pollock d, M. Assafin e, R. Vieira Martins f, J. Berthier g, F. Vachier g, D.P. Cruikshank h, L.F. Lim i, D.E. Reichart j, K.M. Ivarsen j, J.B. Haislip j, A.P. LaCluyze j a Carl Sagan Center, SETI Institute, 189 Bernardo Ave., Mountain View, CA 94043, USA b Earth and Planetary Sciences, University of Tennessee, 306 Earth and Planetary Sciences Building, Knoxville, TN 37996-1410, USA c SRON, Netherlands Institute for Space Research, Low Energy Astrophysics, Postbus 800, 9700 AV Groningen, Netherlands d Appalachian State University, Department of Physics and Astronomy, 231 CAP Building, Boone, NC 28608, USA e Observatorio do Valongo, UFRJ, Ladeira Pedro Antonio 43, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil f Observatório Nacional, MCT, R. General José Cristino 77, CEP 20921-400 Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil g Institut de mécanique céleste et de calcul des éphémérides, Observatoire de Paris, Avenue Denfert-Rochereau, 75014 Paris, France h NASA, Ames Research Center, Mail Stop 245-6, Moffett Field, CA 94035-1000, USA i NASA, Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, MD 20771, USA j Physics and Astronomy Department, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC 27514, USA article info abstract Article history: We collected mid-IR spectra from 5.2 to 38 lm using the Spitzer Space Telescope Infrared Spectrograph Available online 2 October 2012 of 28 asteroids representative of all established types of binary groups. -

A Study of Asteroid Pole-Latitude Distribution Based on an Extended

Astronomy & Astrophysics manuscript no. aa˙2009 c ESO 2018 August 22, 2018 A study of asteroid pole-latitude distribution based on an extended set of shape models derived by the lightcurve inversion method 1 1 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 J. Hanuˇs ∗, J. Durechˇ , M. Broˇz , B. D. Warner , F. Pilcher , R. Stephens , J. Oey , L. Bernasconi , S. Casulli , R. Behrend8, D. Polishook9, T. Henych10, M. Lehk´y11, F. Yoshida12, and T. Ito12 1 Astronomical Institute, Faculty of Mathematics and Physics, Charles University in Prague, V Holeˇsoviˇck´ach 2, 18000 Prague, Czech Republic ∗e-mail: [email protected] 2 Palmer Divide Observatory, 17995 Bakers Farm Rd., Colorado Springs, CO 80908, USA 3 4438 Organ Mesa Loop, Las Cruces, NM 88011, USA 4 Goat Mountain Astronomical Research Station, 11355 Mount Johnson Court, Rancho Cucamonga, CA 91737, USA 5 Kingsgrove, NSW, Australia 6 Observatoire des Engarouines, 84570 Mallemort-du-Comtat, France 7 Via M. Rosa, 1, 00012 Colleverde di Guidonia, Rome, Italy 8 Geneva Observatory, CH-1290 Sauverny, Switzerland 9 Benoziyo Center for Astrophysics, The Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot 76100, Israel 10 Astronomical Institute, Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, Friova 1, CZ-25165 Ondejov, Czech Republic 11 Severni 765, CZ-50003 Hradec Kralove, Czech republic 12 National Astronomical Observatory, Osawa 2-21-1, Mitaka, Tokyo 181-8588, Japan Received 17-02-2011 / Accepted 13-04-2011 ABSTRACT Context. In the past decade, more than one hundred asteroid models were derived using the lightcurve inversion method. Measured by the number of derived models, lightcurve inversion has become the leading method for asteroid shape determination.