The Case of George Ernest Thompson Edalji

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yscrys 1.Pdf

Across the Colonial Divide: Friendship in the British Empire, 1875-1940 by You-Sun Crystal Chung A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History and Women’s Studies) in the University of Michigan 2014 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Kali A. K. Israel, Chair Professor Adela Pinch Professor Helmut Puff Associate Professor Damon Salesa, University of Auckland © You-Sun Crystal Chung 2014 To my parents, Hyui Kyung Choi and Sye Kyun Chung, My brother June Won Fred Chung, And the memory of my grandmother Junghwa Kim ii Acknowledgements First, I would like to thank my committee Kali Israel, Adela Pinch, Damon Salesa, and especially Helmut Puff, for his generosity and insight since the inception of this project. Leslie Pincus also offered valuable encouragement when it was most keenly felt. This dissertation would not have been possible without the everyday support provided by Lorna Altstetter, Diana Denney, Aimee Germain, and especially Kathleen King. I have been fortunate throughout the process to be sustained by the friendship of those from home as well as those those I met at Michigan. My thanks to those who have demonstrated for me the strength of old ties: Jinok Baek, Yongran Byun Bang Sunghoon, Jeeyun Cho, Kyungeun Cho, Hae mi Choi, Hyewon Choi, Soonyoung Choi, Woojin Choi, Sue Young Chung, Yoonie Chung, YoonYoung Hwang, Jiah Hyun, Won Sun Hyun, Hailey Jang, Claire Kim, Kim Daeyoung, Max Kepler, Eun Hyung Kim, Hyunjoo Kim, Hye Young Kim, Jiwon Kang, Kim Jeongyeon, Jungeun Kim, Minju Kim, Minseung Kim, Nayeon Kim, Soojeong Kim, Woojae Kim, Bora Lee, Dae Jun Lee, Haeyeon Lee, Philip W. -

Arthur & George

The Game Is On—for Real. Arthur & George With Martin Clunes as Sir Arthur Conan Doyle Adapted from Julian Barnes’s acclaimed novel Sundays, September 6 - 20, 2015 at the special time of 8pm ET on MASTERPIECE on PBS Martin Clunes (Doc Martin) stars as Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, the creator of Sherlock Holmes, in a real-life case that inspired the great author to put down his pen and turn detective. Tracing a string of notorious animal mutilations alleged to involve an attorney named George Edalji, Arthur & George airs in three gripping episodes on MASTERPIECE, Sundays, September 6-20, 2015 at the special time of 8pm ET on PBS (check local listings). Arthur & George is adapted from Julian Barnes’s acclaimed novel of the same name, which was a finalist for the Man Booker Prize, the most prestigious literary award in the English-speaking world. Co-starring are Arsher Ali (The Missing) as George Edalji, a mixed-race solicitor living in the English Midlands; Art Malik (Upstairs Downstairs) as his Indian father, an Anglican minister; and Emma Fielding (Cranford) as his Scottish mother. Also appearing are Charles Edwards (Downton Abbey) as Alfred Wood, Sir Arthur’s private secretary; and Hattie Morahan (Sense and Sensibility) as Jean Leckie, the woman that Doyle befriended while his wife was gravely ill. The three-part drama won plaudits from the press during its recent UK broadcast, with The Sunday Telegraph (London) hailing it as “thoroughly enjoyable … Clunes proves exceptionally winning as the widowed writer and sometime crusader for justice, Arthur Conan Doyle, who finds a new zest for life when he comes across the curious case of George Edalji.” The Edalji case saw an improbable defendant, mild-mannered lawyer George Edalji, convicted for mutilating a pony and, by implication, a host of other farm animals in a slashing spree known as the Great Wyrley Outrages. -

Arthur & George Por Julian Barnes – Na Pista De Um Crime Sem Castigo

UNIVERSIDADE DE TRÁS-OS-MONTES E ALTO DOURO Arthur & George por Julian Barnes – na Pista de um Crime sem Castigo DISSERTAÇÃO DE MESTRADO EM CULTURA E LITERATURA INGLESAS ANABELA CRISTINA ANTUNES PEREIRA Vila Real, 2008 1 Dissertação elaborada no âmbito do Mestrado em Cultura e Literatura Inglesas e apresentada à Universidade de Trás-os-Montes e Alto Douro. Trabalho orientado pela Professora Doutora Laura Fernanda Bulger. 2 Ao meu avô, José da Costa. 3 ÍNDICE Agradecimentos 5 Resumo 6 Abstract 7 Introdução 8 1. Os caminhos tortuosos do Realismo Inglês 10 1.1 - A problemática em torno do Realismo 10 1.2- Intimismo e auto-reflexão 13 1.3 - O romance não-realista de Julian Barnes 16 2. Arthur & George e a ficção da Pós-Modernidade 19 2.1 - A questão da pós-modernidade 19 2.2 - Ambiguidades narrativas 24 2.3 - A reconstituição paródica do passado 35 3. “The Englishness” 38 3.1- England, England - Uma visão paródica de “Englishness” 38 3.2- Arthur and George, “the unoficial Englishmen” 46 4. Perspectivas Dialógicas 52 4.1- A narração omnisciente em Arthur and George 52 4.2- Arthur 58 4.3- George 66 4.4- Arthur and George 75 5. Subversão da lógica detectivesca 83 5.1- Romance Policial 83 5.2- Veredicto 93 5.3- A verdade póstuma do crime 98 Conclusão 104 Referências bibliográficas 107 4 AGRADECIMENTOS Os meus sinceros agradecimentos à Professora Doutora Laura Bulger pelos seus ensinamentos e pela sua orientação atenta durante todos estes meses. A todos os meus Professores de Mestrado, pelo seu profissionalismo e disponibilidade. -

Julian Barnes, Arthur & George

ACTA LITTERARIA COMPARATIVA The Anonymous Letter in the Construction of Racial Prejudice (Julian Barnes, Arthur & George) Anoniminio laiško vaidmuo konstruojant rasizmą Juliano Barneso romane Arthuras & George‘as Oksana WERETIUK University of Rzeszow Institute of English Studies Comparative Literary and Cultural Studies Al. mjr. W. Kopisto 2B 35-315 Rzeszów, Poland [email protected] Summary The article is an attempt to provide a postcolonial interpretation of racism in Arthur & George, a historical novel by Julian Barnes. The main character, George Edalji, the son of an English pastor of Indian descent and a Scottish mother identi- fies himself as “full English.” His birth, citizenship, education, religion, profes- sion confirm his British status. More and more often, the intelligent, slow, too much introverted “hybrid” is exposed to acts fueled by the racial intolerance of the local community members, which occur behind the rectory fence of the vicar- age. All the time the Edalji family suffers from the attacks of a poisonous racist’s anonymous letters. In Arthur & George, the author of Sherlock Holmes runs a private investigation in defense of George. He carefully reads all the letters and becomes certain of a growing aversion to the Edaljis and especially to the intelli- gent George, a solicitor. The novel shows race-based aversion to the dark-skinned neighbor, whose otherness was sufficient evidence of his guilt, not only for the local community, but also for most of British society, including public institutions such as the police, courts, and even the government. With the help of the anony- mous letters, introduced into the plot, Barnes does not present racism as an act of overt discrimination or aggression, as Victorian-era British society is apparently free from racial prejudice. -

Reading Group Guide Spotlight

Spotlight on: Reading Group Guide Arthur & George Author: Julian Barnes Born January 9, 946, in Leicester, England; son of Name: Julian Barnes Albert Leonard (a French teacher) and Kaye (a French Born: January 9, 946 teacher) Barnes; married Pat Kavanagh (a literary Education: Magdalen agent), 979. Education: Magdalen College, Oxford, College, Oxford, B.A. B.A. (with honors), 968. Addresses: Agent: Peters, (with honors) Fraser, and Dunlop Ltd., Drury House, 34-43 Russell St., Address: Peters, Fraser, and London WC2B 5HA, England. Dunlop Ltd., Drury House, 34-43 Russell St., London WC2B 5HA, England. Career: Freelance writer, 972—. Lexicographer for Oxford English Dictionary Supplement, Oxford, England, 969-72; New Statesman, London, England, assistant literary editor, 977-78, television critic, 977-8; Sunday Times, London, deputy literary editor, 979-8; Observer, London, television critic, 982-86; London correspondent for New Yorker magazine, 990-94. Awards: Somerset Maugham Prize, 980, for Metroland; Booker Prize nomination, 984, Geoffrey Faber Memorial Prize, and Prix Medicis, all for Flaubert’s Parrot; American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters award, 986, for work of distinction; Prix Gutembourg, 987; Premio Grinzane Carour, 988; Prix Femina for Talking It Over, 992; Shakespeare Prize (Hamburg), 993; Officier de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres; shortlisted for Booker Prize, 998, for England, England. Writings: Novels Metroland, St. Martin’s Press (New York, NY), 980. Before She Met Me, Jonathan Cape (London, England), 982, McGraw-Hill (New York, NY), 986. Flaubert’s Parrot, Jonathan Cape (London, England), 984, Knopf (New York, NY), 985. Staring at the Sun, Jonathan Cape (London, England), 986, Knopf (New York, NY), 987. -

From the Actual to the Possible.Pdf

Wenshan Review of Literature and Culture.Vol 6.2.June 2013.159-190. From the Actual to the Possible: Cosmopolitan Articulation of Englishness in Julian Barnes’ Arthur & George Cheng-Hao Yang ABSTRACT Julian Barnes’ Arthur & George (2005) critiques the nationalistic particularism of English identity and offers the possibility of reconfiguring Englishness. An institutionalized reading of the novel would draw the reader’s attention to the issues of racism and miscarriages of legal justice, and most reviews conform to these readerly expectations. I would argue that this novel works on the deconstruction of the total and totalized English identity, and this deconstruction is coupled with a cosmopolitan articulation of Englishness to facilitate ethical relation and solidarity between the two “unofficial Englishmen”: Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and George Edalji. The deconstruction of the English identity does not discredit the value of national identity, but it turns away from a totalized national identity. In Postcolonial Melancholia, Paul Gilroy asks, “ . what critical perspectives might nurture the ability and the desire to live with difference on an increasingly divided but also convergent planet?” (3). A cosmopolitan articulation of national identity could be a response to Gilroy’s question, as it will shift the focus of the discussion on Englishness from the actual—the entrenched, static and prejudiced national identity, to the possible—the ethical engagement, and the productive relatedness of existent differences in the singularity of each subject. In Arthur & George, differences do not constitute the obstacle between the two main characters, but rather the very reason for Arthur to reach out toward George. KEY WORDS: Englishness, Julian Barnes, Arthur & George, ethical relation, cosmopolitanism I would like to express my gratitude to the anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments and suggestions. -

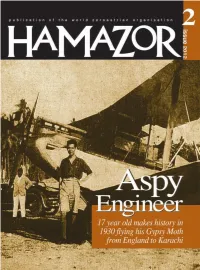

Aspy Meherwan Engineer

HAMAZOR - ISSUE 2 2012 Artist & Social Worker, Jimmy Engineer with Mother Teresa - p34 C o n t e n t s 04 Message from the Chairman, WZO 05 WZO celebrates Nowruz - sammy bhiwandiwalla 06 WZO Trust - An overview for 2011 - dinshaw tamboly 09 Zoroastrianism’s Influence on Christanity - keki bhote 11 Chawk blessings - shiraz engineer 12 The Avesta & its language at Oxford University from 1886 to present - elizabeth tucker COVER 15 The School of Religion at Claremont - arman ariane 16 An After-world itinerary - farrokh vajifdar Photograph of Aspy 21 Prayer & Worship - dina mcintyre Engineer when he landed in Karachi from 25 Legacy of Ancient Iran - philip kreyenbroek London in his Gypsy 28 “My little book of Zoroastrian prayer” - review magdalena rustomji Moth - an achievement 29 “Discovering Ashavan” - review debbie starzynski that made history. 30 Making a difference - marjorie husain Courtesy Cyrus Aspy Engineer 37 The Eighth Outrage - yesmin madon PHOTOGRAPHS 39 In the recall of times lost - jamsheed marker 44 Dilemmas around Development - homi khushrokhan Courtesy of individuals 47 Aspy Meherwan Engineer - rusi sorabji whose articles appear in the magazine or as 54 The Origins of sexual freedom in the West - soonu engineer mentioned 59 Reliable sites on Zoroastrianism on the Internet 60 Feeding the homeless one meal swipe at a time - rustom birdie 63 Nowrojee & Sons General Store www.w-z-o.org 1 In loving memory of my son Cyrus Happy Minwalla M e m b e r s o f t h e M a n a g i n g C o m m i t t e e London, England The World Zoroastrian -

Quando Conan Doyle Indaga: Il Centenario Del Caso Edalji Tra Realtà E Finzione

Roberta Mullini – Università di Urbino Quando Conan Doyle indaga: il centenario del caso Edalji tra realtà e finzione [email protected] 1. I FATTI Se si inserisce sul sito di Google il nome “George Edalji” si scopre che vi sono moltissimi riferimenti: direi che oggi (2007) ciò deriva dal fatto che due anni fa uscì il romanzo Arthur & George del famoso scrittore inglese Julian Barnes, una ricostruzione romanzata degli avvenimenti che misero in contatto Arthur Co- nan Doyle con le vicende di questo sconosciuto signore di origine Parsi. Pri- ma, infatti, ritengo che George Edalji fosse noto solo ai biografi di Doyle, ai lettori di tali biografie e a coloro che si interessano della storia giudiziaria in- glese del primo Novecento, mentre penso che ben poco ne sapessero gli ap- passionati di Sherlock Holmes. Nel 1903, dopo un processo giudicato, a posteriori, poco corretto e che aveva usato prove inaccettabili e tendenziose, George Edalji – giovane legale, figlio di un pastore anglicano di origine Parsi abitante a Great Wyrley nella re- gione del South Staffordshire, poco lontano da Birmingham, e di una donna scozzese – fu condannato a sette anni di prigione in quanto ritenuto colpevole di aver mutilato e ucciso un cavallo e di aver scritto una lunga serie di lettere anonime. Suscitate dalle rimostranze della famiglia, presto iniziarono campagne in difesa dell’imputato, tanto che – senza alcuna spiegazione – Edalji fu liberato alla fine del 1906. Doyle venne a conoscenza del caso dalla stampa che ne dibat- té a lungo (a favore e contro), tanto che all’inizio di gennaio del 1907 i due si incontrarono. -

Julian Barnes, Conan Doyle, Sherlock Holmes and the Edalji Case

International Commentary on Evidence Volume 4, Issue 2 2006 Article 3 Boxes in Boxes: Julian Barnes, Conan Doyle, Sherlock Holmes and the Edalji Case D. Michael Risinger∗ ∗Seton Hall University School of Law, [email protected] Copyright c 2007 The Berkeley Electronic Press. All rights reserved. Boxes in Boxes: Julian Barnes, Conan Doyle, Sherlock Holmes and the Edalji Case∗ D. Michael Risinger Abstract The topic of this symposium has allowed me to indulge myself in addressing a number of pet complaints, ranging from the pernicious effects of Sherlock Holmes on the self-image of forensic scientists, to the dangers of relying on fiction in the teaching of evidence. It is not often that one has the opportunity to deal with such a diverse catalogue of peeves in a single piece, and still claim that they are central to the topic set out by a symposium organizer. We owe this to the special nature of the subject for this symposium: A novel about the actual investigation of a real criminal case by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, who of course is best remembered as the writer who created Sherlock Holmes, a fictional character (for those of you who were unsure). What we are to examine is art imitating life imitating art imitating life. The first “art” in that sentence is the art brought to bear by the novelist Julian Barnes in the creation of his 2005 novel Arthur & George. This novel is a novel of a particular sort. It is based on an actual episode of crime and punishment, and is peopled dominantly with characters who had real historical existence. -

The Postmodern Condition: Inhumanity and Agnosticism in Barnes's Arthur and George (2005) and Nothing to Be Frightened of (200

MINSTRY OF HIGHER EDUCATION AND SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH UNIVERSITY OF ORAN-SENIA FACULTY OF LETTERS & LANGUAGES DEPARTMENT OF ANGLO-SAXON LANGUAGES Doctoral School of English: 2009 SECTION OF ENGLISH The Postmodern Condition: Inhumanity and Agnosticism in Barnes’s Arthur and George (2005) and Nothing to be Frightened of (2008) Submitted in partial fulfilment for the degree of Magister in British and Commonwealth Studies: British Literature by Nariman LARBI soutenue le 09/05/2013 Board of Examiners Chairwoman: Prof. R. YACINE, UNIVERSITY OF ORAN Supervisor : Prof. A.BAHOUS, UNIVERSITY OF MOSTAGANEM Examiner : Dr L. MOULFI, UNIVERSITY OF ORAN M.C.A. Examiner : Dr B. BELMEKKI, UNIVERSITY OF ORAN M.C.A. 2012-2013 To my Father, my Mother and Sister Y.L Abstract The focal point of this dissertation is to demonstrate the continuous demise of religion and Man’s hopeless sustainability of the belief in a divine state/purpose in the face of the post-modern reality. The purpose of this modest thesis is to prove that Julian Barnes’s anxiety in his admission of God and religion as a divine set of abstract foundation resides in the validity of the truthfulness, or even the authenticity of their nature and essence. The latter being the most doubted characteristic which brings about Man’s sceptical position concerning the transcendental. Hence it is the lack of evidence; earthly tangible evidence though, which renders the transcendental uncertain of its being. Postmodernism values the scientifically and empirically sustained truth, the latter being of an eminent foreground in a century which relies on materialistic evidence to forge judgement, knowledge, and sustainability for its legitimacy.