An Investigation of the Functions of Leaf Surface Modification in The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Location of Population Allocasuarina Emuina

N SOURCE: JFP Consultants CLIENT TITLE Aveo Group Limited LEGEND 0 25m (Ref: B2403-472A Tree Pickup.pdf) FIGURE 7 LOCATION OF PROJECT ALLOCASUARINA Allocasuarina emuina SCALE: 1 : 1000 @ A3 Protected Plants Survey Report Population 1 : 1 000 PREPARED: BW Coolum Ridges Southern Interchange EMUINA JWA PTY LTD Coolum Ridges Estates, QLD DATE: 06 August 2015 Ecological Consultants Sunshine Coast Regional Council LGA FILE: Q01058_Emuina.cdr POPULATION ALLOCASUARINA EMUINA LOCATION Legend Southern Interchange Extent of Works Survey Area (100m Buffer) Allocasuarina emuina Population N Community 1 -Eucalyptus racemosa woodland Community 2 -Melaleuca quinquenervia closed woodland Community 3 - Wallum heathland Community 4 -Banksia aemula low open woodland Community 5 - Closed sedgeland SOURCE: JWA Site Investigations; Calibre Consulting CLIENT TITLE (X-N07071-BASE.dwg); JFP Consultants (B2403-472A Aveo Group Limited FIGURE 9 050m 100m Tree Pickup.dwg); Google Earth Aug 2014 Aerial PROJECT Protected Plants Survey Report VEGETATION SCALE: 1 : 3500 @ A3 PREPARED: BW 1 : 3500 Coolum Ridges Southern Interchange COMMUNITIES JWA PTY LTD DATE: 06 August 2015 Ecological Consultants Coolum Ridges Estates, QLD Sunshine Coast Regional Council LGA FILE: Q01058_Veg v2.cdr Protected Plant Survey Report – Coolum Ridges Southern Interchange Conservation Status This vegetation is consistent with RE 12.9-10.4 which has a conservation status of Least Concern under the VMA (1999). 3.3.3.3 Community 2: Melaleuca quinquenervia closed woodland Location and area This community is located on both sides of the Sunshine Motorway between the E. racemosa woodland and the wallum heathland, adjacent to an unnamed tributary of Stumers Creek in the southern portion of the subject site, and in low-lying areas in the northern section (FIGURE 9). -

Open Doman MS Thesis.Pdf

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School Department of Geosciences STABLE ISOTOPE AND LIPID SIGNATURES OF PLANTS ACROSS A CLIMATE GRADIENT: IMPLICATIONS FOR BIOMARKER-BASED PALEOCLIMATE RECONSTRUCTIONS A Thesis in Geosciences by Christine E. Doman 2015 Christine E. Doman Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science August 2015 ii The thesis of Christine E. Doman was reviewed and approved* by the following: Katherine H. Freeman Professor of Geoscience Thesis Advisor Mark Patzkowsky Professor of Geosciences Matthew Fantle Associate Professor of Geosciences Demian Saffer Professor of Geosciences Interim Associate Head of Graduate Programs *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School iii ABSTRACT Plant wax n-alkanes are long, saturated hydrocarbons that form part of the protective, waxy cuticle on leaves. These lipids are pervasive and persistent in soils and sediments and are ideal biomarkers of ancient terrestrial organic matter. In ecosystems dominated by C3 plants, fractionation of carbon and hydrogen isotopes during production of whole leaves and hydrocarbon lipids are well documented, but the sensitivity of isotopic fractionation between leaves and lipids to climate has not been fully investigated. Further, there are few studies of stable isotopes in C4 plant lipids. In both cases, it is unclear if carbon and hydrogen isotopic fractionations during lipid production are sensitive to environmental conditions, such as moisture, or if they reflect inherited characteristics tied to taxonomic or phylogenetic affiliation. This study used a natural climate gradient on the Kohala peninsula of Hawaii to investigate relationships 13 2 between climate and the δ C and δ H values of n-alkanes in three taxa of C3 and two taxa of C4 plants. -

NSW Rainforest Trees Part

This document has been scanned from hard-copy archives for research and study purposes. Please note not all information may be current. We have tried, in preparing this copy, to make the content accessible to the widest possible audience but in some cases we recognise that the automatic text recognition maybe inadequate and we apologise in advance for any inconvenience this may cause. · RESEARCH NOTE No. 35 ~.I~=1 FORESTRY COMMISSION OF N.S.W. RESEARCH NOTE No. 35 P)JBLISHED 197R N.S.W. RAINFOREST TREES PART VII FAMILIES: PROTEACEAE SANTALACEAE NYCTAGINACEAE GYROSTEMONACEAE ANNONACEAE EUPOMATIACEAE MONIMIACEAE AUTHOR A.G.FLOYD (Research Note No. 35) National Library of Australia card number and ISBN ISBN 0 7240 13997 ISSN 0085-3984 INTRODUCTION This is the seventh in a series ofresearch notes describing the rainforest trees of N.S. W. Previous publications are:- Research Note No. 3 (I 960)-N.S.W. Rainforest Trees. Part I Family LAURACEAE. A. G. Floyd and H. C. Hayes. Research Note No. 7 (1961)-N.S.W. Rainforest Trees. Part II Families Capparidaceae, Escalloniaceae, Pittosporaceae, Cunoniaceae, Davidsoniaceae. A. G. Floyd and H. C. Hayes. Research Note No. 28 (I 973)-N.S.W. Rainforest Trees. Part III Family Myrtaceae. A. G. Floyd. Research Note No. 29 (I 976)-N.S.W. Rainforest Trees. Part IV Family Rutaceae. A. G. Floyd. Research Note No. 32 (I977)-N.S.W. Rainforest Trees. Part V Families Sapindaceae, Akaniaceae. A. G. Floyd. Research Note No. 34 (1977)-N.S.W. Rainforest Trees. Part VI Families Podocarpaceae, Araucariaceae, Cupressaceae, Fagaceae, Ulmaceae, Moraceae, Urticaceae. -

The Surface Wax of the Grape Berry: Interactions with Chemical Sprays and Subsequent Susceptibility to Botrytis Infection

The surface wax of the grape berry: interactions with chemical sprays and subsequent susceptibility to Botrytis infection Botrytis hyphae growing over surface of grape berry FINAL REPORT to GRAPE AND WINE RESEARCH & DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION Project Number: CSU 02/01 Principal Investigators: Suzy Rogiers & Melanie Weckert Research Organisation: National Wine & Grape Industry Centre Date: February, 2005 1 The surface wax of the grape berry: interactions with chemical sprays and subsequent susceptibility to Botrytis infection Suzy Y Rogiers National Wine & Grape Industry Centre Melanie Weckert Charles Sturt University National Wine & Grape Industry Centre Locked Bag 588 Charles Sturt University Wagga Wagga, NSW 2678 Locked Bag 588 Ph: 02 6933 2436 Wagga Wagga, NSW 2678 Fax: 02 6933 2107 Ph: 02 6933 2720 Email: Fax: 02 6933 2107 [email protected] Email: [email protected] February, 2005 Copyright: National Wine & Grape Industry Centre Disclaimer: The advice provided in this document is intended as a source of information only. The NWGIC and its employees do not guarantee that the publication is without flaw of any kind or is wholly appropriate for your particular purposes and therefore disclaims all liability for any error, loss or other consequence which may arise from your relying on any information in this publication. 2 Table of Contents 1. Abstract 5 2. Executive summary 6 3. Background 8 4. Project aims and performance targets 9 5. Methods 10 5.1 Field treatments 10 5.2 Cryo-SEM 12 5.3 Botrytis inoculation 12 5.4 Microflora populations count 12 5.5 Statstics 12 6. -

Pigments, Epicuticular Wax and Leaf Nutrients

rch: O ea pe es n A R t c s c e e r s o s Forest Research F Maiti R, et al., Forest Res 2016, 5:2 Open Access DOI: 10.4172/2168-9776.1000170 ISSN: 2168-9776 Research Article Open Access Biodiversity in Leaf Chemistry (Pigments, Epicuticular Wax and Leaf Nutrients) in Woody Plant Species in North-eastern Mexico, a Synthesis Maiti R1*, Rodriguez HG2, Sarkar NC3 and Kumari A4 1Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León, Facultad de Ciencias Forestales, Carr. Nac. No. 85 Km. 45, Linares, Nuevo Leon 67700, México 2Humberto González Rodríguez, Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León, Facultad de Ciencias Forestales, Carr. Nac. No. 85 Km. 45, Linares, Nuevo León 67700, México 3Department of ASEPAN, Institute of Agriculture, Visva-Bharati, PO- Sriniketan, Birbhum (Dist), West Bengal (731 236), India 4Department of Plant Physiology, Professor Jaya Shankar Telangana State Agricultural University, Agricultural College, Polasa, Jagtial, Karimnagar-505 529, India *Corresponding author: Maiti R, Visiting Scientist, Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León, Facultad de Ciencias Forestales, Carr. Nac. No. 85 Km. 45, Linares, Nuevo Leon 67700, México, Tel: 52-8116597090; E-mail: [email protected]/ [email protected] Received date: 11 Jan 2016; Accepted date: 04 Feb 2016; Published date: 06 Feb 2016 Copyright: © 2016 Maiti R, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Abstract The leaves of trees and shrubs possess various chemical components such as leaf pigments, epicuticular wax and various macro and micronutrients. -

Leaf Expansion – an Integrating Plant Behaviour

Plant, Cell and Environment (1999) 22, 1463–1473 COMMISSIONED REVIEW Leaf expansion – an integrating plant behaviour E. VAN VOLKENBURGH Department of Botany, Box 355325, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195, USA ABSTRACT the phase of leaf development contributing most to surface area and shape of the lamina. Leaves expand to intercept light for photosynthesis, to take Leaves can be considered, functionally, as iterated green up carbon dioxide, and to transpire water for cooling and antennae specialized for trapping light energy, absorbing circulation. The extent to which they expand is determined carbon dioxide, transpiring water, and monitoring the envi- partly by genetic constraints, and partly by environmental ronment. The leaf canopy may be made up of many or few, conditions signalling the plant to expand more or less leaf small or large leaves. They may be simple in shape, like the surface area. Leaves have evolved sophisticated sensory monocotyledonous leaves of grasses or dicotyledonous mechanisms for detecting these cues and responding with leaves of sunflower and elm. Or leaves may be more their own growth and function as well as influencing a complex, with intricate morphologies as different as the variety of whole-plant behaviours. Leaf expansion itself is delicate, sensitive structure of the Mimosa leaf is from the an integrating behaviour that ultimately determines canopy magnificent blade of Monstera. Some species, such as development and function, allocation of materials deter- cactus, do not develop leaves at all, but carry out leaf func- mining relative shoot : root volume, and the onset of repro- tions in the stem. Other plants display small leaves in order duction. -

Morphology and Accumulation of Epicuticular Wax on Needles of Douglas-Fir Pseudotsuga( Menziesii Var

Constance A. Harrington1 and William C. Carlson, USDA Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station, 3625 93rd Ave. SW, Olympia, Washington 98512 Morphology and Accumulation of Epicuticular Wax on Needles of Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii var. menziesii) Abstract Past studies have documented differences in epicuticular wax among several tree species but little attention has been paid to changes in accumulation of foliar wax that can occur during the year. We sampled current-year needles from the termi- nal shoots of Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii var. menziesii) in late June/early July, late August and early November. Needles were sampled from two sites that differed in their climate and shoot phenology. Adaxial (upper), abaxial (lower) and cross-sectional surfaces were examined on scanning electron micrographs. Wax thickness increased significantly (P < 0.01) during the year (from 2.9 ± 0.26 µm in late June/early July to 4.4 ± 0.13 µm in early November). Mean wax thick- ness was slightly thicker on adaxial (4.0 ± 0.16 µm) than on abaxial (3.5 ± 0.22 µm) surfaces (P = 0.03). There were no significant differences in wax thickness between needles sampled at the base of the terminal shoot or near the tip of the shoot. Tubular or rod-shaped epicuticular wax crystals were sparsely developed on adaxial surfaces, completely covered abaxial surfaces (including filling all stomatal cavities), and had the same general structure and appearance across sites and sampling dates. Some erosion of epicuticular wax crystals on adaxial surfaces and presence of amorphous wax on abaxial surfaces was observed late in the year when epicuticular wax thickness was the thickest. -

Flying-Fox Dispersal Feasibility Study Cassia Wildlife Corridor, Coolum Beach and Tepequar Drive Roost, Maroochydore

Sunshine Coast Council Flying-Fox Dispersal Feasibility Study Cassia Wildlife Corridor, Coolum Beach and Tepequar Drive Roost, Maroochydore. Environmental Operations May 2013 0 | Page Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 2 Purpose ............................................................................................................................................... 2 Flying-fox Mitigation Strategies .......................................................................................................... 2 State and Federal Permits ................................................................................................................... 4 Roost Management Plan .................................................................................................................... 4 Risk ...................................................................................................................................................... 5 Flying-fox Dispersal Success in Australia ............................................................................................. 6 References .......................................................................................................................................... 7 Cassia Wildlife Corridor ................................................................................................................ 8 Background ........................................................................................................................................ -

Scanning Electron Microscopy of the Leaf Epicuticular Waxes of the Genus Gethyllis L

Soulh Afnc.1n Journal 01 Bol811Y 2001 67 333-343 Copynghl €I NISC Ply LId Pnmed In South Alnca - All ngills leserved SOUTH AFRICAN JOURNAL OF BOTANY ISSN 0254- 5299 Scanning electron microscopy of the leaf epicuticular waxes of the genus Gethyllis L. (Amaryllidaceae) and prospects for a further subdivision C Weiglin Technische Universitat Berlin, Herbarium BTU, Sekr. FR I- I, Franklinstrasse 28-29, 0-10587 Berlin, Germany e-mail: [email protected] Recei ved 23 August 2000, accepled in revised form 19 January 2001 The leaf epicuticular wax ultrastructure of 32 species of ridged rodlets is conspicuous and is interpreted as the genus Gethyllis are for the first time investigated being convergent. In three species wax dimorphism was and discussed. Non-entire platelets were observed in discovered, six species show a somewhat rosette-like 12 species, entire platelets with transitions to granules orientation of non-entire or entire platelets and in four in seven species, membranous platelets in nine species a tendency to parallel orientation of non-entire species and smooth layers in eight species, Only or entire platelets was evident. It seems that Gethyllis, GethyJlis transkarooica is distinguished by its trans from its wax morphology, is highly diverse and versely ridged rodlets. The occurrence of transversely deserves further subdivision. Introduction The outer epidermal cell walls of nearly all land plants are gle species among larger taxa, cu ltivated plants , varieties covered by a cuticle cons isting mainly of cutin, an insoluble and mutants (Juniper 1960, Leigh and Matthews 1963, Hall lipid pOlyester of substituted aliphatic acids and long chain et al. -

Species List Alphabetically by Common Names

SPECIES LIST ALPHABETICALLY BY COMMON NAMES COMMON NAME SPECIES COMMON NAME SPECIES Actephila Actephila lindleyi Native Peach Trema aspera Ancana Ancana stenopetala Native Quince Guioa semiglauca Austral Cherry Syzygium australe Native Raspberry Rubus rosifolius Ball Nut Floydia praealta Native Tamarind Diploglottis australis Banana Bush Tabernaemontana pandacaqui NSW Sassafras Doryphora sassafras Archontophoenix Bangalow Palm cunninghamiana Oliver's Sassafras Cinnamomum oliveri Bauerella Sarcomelicope simplicifolia Orange Boxwood Denhamia celastroides Bennetts Ash Flindersia bennettiana Orange Thorn Citriobatus pauciflorus Black Apple Planchonella australis Pencil Cedar Polyscias murrayi Black Bean Castanospermum australe Pepperberry Cryptocarya obovata Archontophoenix Black Booyong Heritiera trifoliolata Picabeen Palm cunninghamiana Black Wattle Callicoma serratifolia Pigeonberry Ash Cryptocarya erythroxylon Blackwood Acacia melanoxylon Pink Cherry Austrobuxus swainii Bleeding Heart Omalanthus populifolius Pinkheart Medicosma cunninghamii Blue Cherry Syzygium oleosum Plum Myrtle Pilidiostigma glabrum Blue Fig Elaeocarpus grandis Poison Corkwood Duboisia myoporoides Blue Lillypilly Syzygium oleosum Prickly Ash Orites excelsa Blue Quandong Elaeocarpus grandis Prickly Tree Fern Cyathea leichhardtiana Blueberry Ash Elaeocarpus reticulatus Purple Cherry Syzygium crebrinerve Blush Walnut Beilschmiedia obtusifolia Red Apple Acmena ingens Bollywood Litsea reticulata Red Ash Alphitonia excelsa Bolwarra Eupomatia laurina Red Bauple Nut Hicksbeachia -

Characterization and Chemical Composition of Epicuticular Wax from Banana Leaves Grown in Northern Thailand

Songklanakarin J. Sci. Technol. 39 (4), 509-516, Jul - Aug. 2017 http://www.sjst.psu.ac.th Original Article Characterization and chemical composition of epicuticular wax from banana leaves grown in Northern Thailand Suporn Charumanee1*, Songwut Yotsawimonwat 1, Panee Sirisa-ard 1, and Kiatisak Pholsongkram2 1 Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Faculty of Pharmacy, Chiang Mai University, Mueang, Chiang Mai, 50200 Thailand 2Department of Food Science and Technology, Faculty of Sciences, Payap University, Mueang, Chiang Mai, 50000 Thailand Received: 22 April 2016; Revised: 2 July 2016; Accepted: 16 July 2010 Abstract This study aimed to investigate the physicochemical properties and chemical composition of epicuticular wax extracted from leaves of Kluai Namwa, a banana cultivar which is widely grown in Northern Thailand. Its genotype was identified by a botanist. The wax was extracted using solvent extraction. The fatty acid profiles and physicochemical properties of the wax namely melting point, congealing point, crystal structures and polymorphism, hardness, color, and solubility were examined and compared to those of beeswax, carnauba wax and paraffin wax. The results showed that the genotype of Kluai Namwa was Musa acuminata X M. balbisiana (ABB group) cv. Pisang Awak. The highest amount of wax extracted was 274 g/cm2 surface area. The fatty acid composition and the physicochemical properties of the wax were similar to those of carnauba wax. It could be suggested that the banana wax could be used as a replacement for carnauba wax in various utilizing areas. Keywords: epicuticular wax, banana wax, Kluai Namwa, Musa spp. carnauba wax 1. Introduction air pollution. However, it is interesting that, the outermost part of banana leaf is covered with lipid substance, which is Banana (Musa spp.) is one of the most widely so-called the epicuticular wax. -

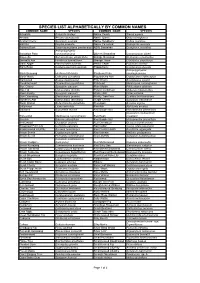

Kingdom Class Family Scientific Name Common Name I Q a Records

Kingdom Class Family Scientific Name Common Name I Q A Records animals amphibians Bufonidae Rhinella marina cane toad Y 12 animals amphibians Hylidae Litoria nasuta striped rocketfrog C 4/1 animals amphibians Hylidae Litoria peronii emerald spotted treefrog C 4 animals amphibians Hylidae Litoria rubella ruddy treefrog C 1/1 animals amphibians Hylidae Litoria wilcoxii eastern stony creek frog C 7 animals amphibians Hylidae Litoria gracilenta graceful treefrog C 3 animals amphibians Hylidae Litoria latopalmata broad palmed rocketfrog C 2 animals amphibians Hylidae Litoria cooloolensis Cooloola sedgefrog NT 1/1 animals amphibians Hylidae Litoria olongburensis wallum sedgefrog V V 1 animals amphibians Hylidae Litoria fallax eastern sedgefrog C 17 animals amphibians Hylidae Litoria freycineti wallum rocketfrog V 1 animals amphibians Limnodynastidae Limnodynastes tasmaniensis spotted grassfrog C 1 animals amphibians Limnodynastidae Limnodynastes terraereginae scarlet sided pobblebonk C 5 animals amphibians Limnodynastidae Platyplectrum ornatum ornate burrowing frog C 2 animals amphibians Limnodynastidae Limnodynastes peronii striped marshfrog C 11 animals amphibians Limnodynastidae Adelotus brevis tusked frog V 2 animals amphibians Myobatrachidae Crinia parinsignifera beeping froglet C 2 animals amphibians Myobatrachidae Mixophyes fasciolatus great barred frog C 2 animals amphibians Myobatrachidae Pseudophryne raveni copper backed broodfrog C 3 animals amphibians Myobatrachidae Mixophyes iteratus giant barred frog E E 9 animals amphibians Myobatrachidae