Public Portraits and Portrait Publics Valentijn Byvanck New York University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Key Facts About Kenmore, Ferry Farm, and the Washington and Lewis Families

Key Facts about Kenmore, Ferry Farm, and the Washington and Lewis families. The George Washington Foundation The Foundation owns and operates Ferry Farm and Historic Kenmore. The Foundation is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization. The Foundation (then known as the Kenmore Association) was formed in 1922 in order to purchase Kenmore. The Foundation purchased Ferry Farm in 1996. Historic Kenmore Kenmore was built by Fielding Lewis and his wife, Betty Washington Lewis (George Washington’s sister). Fielding Lewis was a wealthy merchant, planter, and prominent member of the gentry in Fredericksburg. Construction of Kenmore started in 1769 and the family moved into their new home in the fall of 1775. Fielding Lewis' Fredericksburg plantation was once 1,270 acres in size. Today, the house sits on just one city block (approximately 3 acres). Kenmore is noted for its eighteenth-century, decorative plasterwork ceilings, created by a craftsman identified only as "The Stucco Man." In Fielding Lewis' time, the major crops on the plantation were corn and wheat. Fielding was not a major tobacco producer. When Fielding died in 1781, the property was willed to Fielding's first-born son, John. Betty remained on the plantation for another 14 years. The name "Kenmore" was first used by Samuel Gordon, who purchased the house and 200 acres in 1819. Kenmore was directly in the line of fire between opposing forces in the Battle of Fredericksburg in 1862 during the Civil War and took at least seven cannonball hits. Kenmore was used as a field hospital for approximately three weeks during the Civil War Battle of the Wilderness in 1864. -

Carlyle Connection Sarah Carlyle Herbert’S Elusive Spinet - the Washington Connection by Richard Klingenmaier

The Friends of Carlyle House Newsletter Spring 2017 “It’s a fine beginning.” CarlyleCarlyle Connection Sarah Carlyle Herbert’s Elusive Spinet - The Washington Connection By Richard Klingenmaier “My Sally is just beginning her Spinnet” & Co… for Miss Patsy”, dated October 12, 1761, George John Carlyle, 1766 (1) Washington requested: “1 Very good Spinit (sic) to be made by Mr. Plinius, Harpsichord Maker in South Audley Of the furnishings known or believed to have been in John Street Grosvenor Square.” (2) Although surviving accounts Carlyle’s house in Alexandria, Virginia, none is more do not indicate when that spinet actually arrived at Mount fascinating than Sarah Carlyle Herbert’s elusive spinet. Vernon, it would have been there by 1765 when Research confirms that, indeed, Sarah owned a spinet, that Washington hired John Stadler, a German born “Musick it was present in the Carlyle House both before and after Professor” to provide Mrs. Washington and her two her marriage to William Herbert and probably, that it children singing and music lessons. Patsy was to learn to remained there throughout her long life. play the spinet, and her brother Jacky “the fiddle.” Entries in Washington’s diary show that Stadler regularly visited The story of Mount Vernon for the next six years, clear testimony of Sarah Carlyle the respect shown for his services by the Washington Herbert’s family. (3) As tutor Philip Vickers Fithian of Nomini Hall spinet actually would later write of Stadler, “…his entire good-Nature, begins at Cheerfulness, Simplicity & Skill in Music have fixed him Mount Vernon firm in my esteem.” (4) shortly after George Beginning in 1766, Sarah (“Sally”) Carlyle, eldest daughter Washington of wealthy Alexandria merchant John Carlyle and married childhood friend of Patsy Custis, joined the two Custis Martha children for singing and music lessons at the invitation of Dandridge George Washington. -

Seth Eastman, a Portfolio of North American Indians Desperately Needed for Repairs

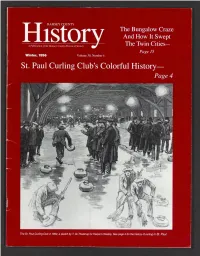

RAMSEY COUNTY The Bungalow Craze And How It Swept A Publication of the Ramsey County Historical Society The Twin Cities— Page 15 Winter, 1996 Volume 30, Number 4 St. Paul Curling Club’s Colorful History The St. Paul Curling Club in 1892, a sketch by T. de Thulstrup for Harper’s Weekly. See page 4 for the history of curling in S t Paul. RAMSEY COUNTY HISTORY Executive Director Priscilla Famham Editor Virginia Brainard Kunz WARREN SCHABER 1 9 3 3 - 1 9 9 5 RAMSEY COUNTY HISTORICAL SOCIETY The Ramsey County Historical Society lost a BOARD OF DIRECTORS good friend when Ramsey County Commis Joanne A. Englund sioner Warren Schaber died last October Chairman of the Board at the age of sixty-two. John M. Lindley CONTENTS The Society came President to know him well Laurie Zehner 3 Letters during the twenty First Vice President years he served on Judge Margaret M. Mairinan the Board of Ramsey Second Vice President 4 Bonspiels, Skips, Rinks, Brooms, and Heavy Ice County Commission Richard A. Wilhoit St. Paul Curling Club and Its Century-old History Secretary ers. We were warmed by his steady support James Russell Jane McClure Treasurer of the Society and its work. Arthur Baumeister, Jr., Alexandra Bjorklund, 15 The Bungalows of the Twin Cities, With a Look Mary Bigelow McMillan, Andrew Boss, A thoughtful Warren We remember the Thomas Boyd, Mark Eisenschenk, Howard At the Craze that Created Them in St. Paul Schaber at his first County big things: the long Guthmann, John Harens, Marshall Hatfield, Board meeting, January 6, series of badly- Liz Johnson, George Mairs, III, Mary Bigelow Brian McMahon 1975. -

1833-1834 Drawings of Mato-Tope and Sih-Chida

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Theses, Dissertations, and Student Creative Activity, School of Art, Art History and Design Art, Art History and Design, School of 2011 Stealing Horses and Hostile Conflict: 1833-1834 Drawings of Mato-Tope and Sih-Chida Kimberly Minor University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/artstudents Part of the American Art and Architecture Commons, and the Art and Design Commons Minor, Kimberly, "Stealing Horses and Hostile Conflict: 1833-1834 Drawings of Mato-Tope and Sih-Chida" (2011). Theses, Dissertations, and Student Creative Activity, School of Art, Art History and Design. 17. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/artstudents/17 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Art, Art History and Design, School of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations, and Student Creative Activity, School of Art, Art History and Design by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Stealing Horses and Hostile Conflict: 1833-34 Drawings of Mato-Tope and Sih-Chida By Kimberly Minor Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts Major: Art History Under the Supervision of Professor Wendy Katz Lincoln, Nebraska April 2011 Stealing Horses and Hostile Conflict: 1833-34 Drawings of Mato-Tope and Sih-Chida Kimberly Minor, M.A. University of Nebraska, 2011 Advisor: Wendy Katz The first documented Native American art on paper includes the following drawings at the Joslyn Art Museum in Omaha, Nebraska: In the Winter, 1833-1834 (two versions) by Sih-Chida (Yellow Feather) and Mato-Tope Battling a Cheyenne Chief with a Hatchet (1834) by Mato-Tope (Four Bears) as well as an untitled drawing not previously attributed to the latter. -

Examine the Exquisite Portraits of the American Indian Leaders Mckenney

Examine the exquisite portraits of the American Indian leaders McKenney, Thomas, and James Hall, History of the Indian Tribes of North America. Philadelphia: Edward C. Biddle (parts 1-5), Frederick W. Greenough (parts 6-13), J.T. Bowen (part 14), Daniel Rice and James G. Clark (parts 15-20), [1833-] 1837-1844 20 Original parts, folio (21.125 x 15.25in.: 537 x 389 mm.). 117 handcolored lithographed portraits after C. B. King, 3 handcolored lithographed scenic frontispieces after Rindisbacher, leaf of lithographed maps and table, 17 pages of facsimile signatures of subscribers, leaf of statements of the genuiness of the portrait of Pocahontas, part eight with the printed notice of the correction of the description of the War Dance and the cancel leaf of that description (the incorrect cancel and leaf in part 1), part 10 with erratum slip, part 20 with printed notice to binders and subscribers, title pages in part 1 (volume 1, Biddle imprint 1837), 9 (Greenough imprint, 1838), 16 (volume 2, Rice and Clark imprint, 1842), and 20 (volume 3, Rice and Clark imprint, 1844); some variously severe but, usually light offsetting and foxing, final three parts with marginal wormholes, not affecting text or images. Original printed buff wrappers; part 2 with spine lost and rear wrapper detached, a few others with spines shipped, part 11 with sewing broken and text and plates loose, part 17 with large internal loss of front wrapper affecting part number, some others with marginal tears or fraying, some foxed or soiled. Half maroon morocco folding-case, gilt rubbed. FIRST EDITION, second issue of title-page of volume 1. -

23 League in New York Before They Were Purchased by Granville

is identical to a photograph taken in 1866 (fig. 12), which includes sev- eral men and a rowboat in the fore- ground. From this we might assume that Eastman, and perhaps Chapman, may have consulted a wartime pho- tograph. His antebellum Sumter is highly idealized, drawn perhaps from an as-yet unidentified print, or extrapolated from maps and plans of the fort—child’s play for a master topographer like Eastman. Coastal Defenses The forts painted by Eastman had once been the state of the art, before rifled artillery rendered masonry Fig. 11. Seth Eastman, Fort Sumter, South Carolina, After the War, 1870–1875. obsolete, as in the bombardment of Fort Sumter in 1861 and the capture of Fort Pulaski one year later. By 1867, when the construction of new Third System fortifications ceased, more than 40 citadels defended Amer- ican coastal waters.12 Most of East- man’s forts were constructed under the Third System, but few of them saw action during the Civil War. A number served as military prisons. As commandant of Fort Mifflin on the Delaware River from November 1864 to August 1865, Col. Eastman would have visited Fort Delaware on Pea Patch Island, located in the river channel between Wilmington and New Castle, Delaware. Channel-dredging had dumped tons of spoil at the northern end of the island, land upon which a miserable prison-pen housed enlisted Confederate pris- oners of war. Their officers were Fig. 12. It appears that Eastman used this George N. Barnard photograph, Fort quartered within the fort in relative Sumter in April, 1865, as the source for his painting. -

![Thomas Seir Cummings Correspondence and Printed Material [Microfilm]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0114/thomas-seir-cummings-correspondence-and-printed-material-microfilm-800114.webp)

Thomas Seir Cummings Correspondence and Printed Material [Microfilm]

Thomas Seir Cummings correspondence and printed material [microfilm] Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 1 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 1 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 1 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 2 Container Listing ...................................................................................................... Thomas Seir Cummings correspondence and printed material [microfilm] AAA.cummthom Collection Overview Repository: Archives of American Art Title: Thomas Seir Cummings correspondence and printed material [microfilm] Identifier: AAA.cummthom Date: 1826-1893 Creator: Cummings, Thomas Seir, 1804-1894 Extent: 1 Microfilm reel Language: English . Administrative Information Acquisition Information Lent for microfilming 1958 by the Century Association. -

Mackenzie, Donald Ralph. PAINTERS in OHIO, 1788-1860, with a BIOGRAPHICAL INDEX

This dissertation h been microfilmed exactly as received Mic 61—925 MacKENZIE, Donald Ralph. PAINTERS IN OHIO, 1788-1860, WITH A BIOGRAPHICAL INDEX. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1960 Fine A rts University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arltor, Michigan Copyright by Donald Ralph MacKenzie 1961 PAINTERS IN OHIO, 1788-1860 WITH A BIOGRAPHICAL INDEX DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy In the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Donald Ralph MacKenzie, B. A., M. S. ****** The Ohio State University 1960 Approved by /Adviser* School oC Fine and Applied Arts PREFACE In 1953, when the author was commissioned to assemble and catalogue the many paintings owned by the Ohio Historical Society, it quickly became apparent that published reference works on early mid- western painters were sadly lacking. At that time the only source books were the standard biographical indexes of American artists, such as Mallett's Index of Artists and Mantle Fielding's Dictionary of Amer ican Painters. Sculptors and Engravers. The mimeographed WPA Histori cal Survey American Portrait Inventory (1440 Early American Portrait Artists I6b3-1860) furnished a valuable research precedent, which has since been developed and published by the New York Historical Society as the Dictionary of Artists in America 1564-1860. While this last is a milestone in research in American art history, the magnitude of its scope has resulted in incomplete coverage of many locales, especially in the Middlewest where source material is both scarce and scattered. The only book dealing exclusively with the Ohio scene is Edna Marie Clark's Ohio Art and Artists, which was published in 1932. -

Historic-Register-OPA-Addresses.Pdf

Philadelphia Historical Commission Philadelphia Register of Historic Places As of January 6, 2020 Address Desig Date 1 Desig Date 2 District District Date Historic Name Date 1 ACADEMY CIR 6/26/1956 US Naval Home 930 ADAMS AVE 8/9/2000 Greenwood Knights of Pythias Cemetery 1548 ADAMS AVE 6/14/2013 Leech House; Worrell/Winter House 1728 517 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 519 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 600-02 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 2013 601 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 603 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 604 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 605-11 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 606 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 608 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 610 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 612-14 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 613 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 615 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 616-18 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 617 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 619 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 629 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 631 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 1970 635 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 636 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 637 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 638 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 639 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 640 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 641 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 642 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 643 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 703 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 708 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 710 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 712 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 714 ADDISON ST Society Hill -

SULLY, THOMAS Date

Docent Handbook - Artist Fact Sheet Artist Name: SULLY, THOMAS Date: 1783-1872 Nationality: American, born English Title/Date: The Student (Rosalie Kemble Sully), 1848 Size: 30 ½ x 26 ¼ inches Medium: Oil on canvas Gallery Location: 4th Floor, Gallery 2 Salient Characteristics of this Work: - Portrait of the artist’s daughter, Rosalie Kemble Sully (1818-1847) - Rosalie was also an artist, a painter of miniatures, having been tutored by her father - Began on November 5th, 1848 and completed on December 18th, according to Sully’s record book - Three portraits of Rosalie as a student exist, another version completed in 1937, before her death at age 29 - Seated, resting figure with crossed hands on portfolio, holding pencil; lampshade casts shadow over face; elongated neck is characteristic of the romantic style Information Narrative: - 1783, born to actors in Horncastle, Lincolnshire, England - 1792, emigrated to the U.S. with his family and settled in Charleston, South Carolina - 1799, moved to Virginia to live with his older brother Lawrence, a painter of miniatures - 1804, Lawrence died and Sully took up the care of his brother’s widow, Sarah, and three young children - 1806, married Sarah and moved to New York because marriage to a brother’s widow was illegal in Virginia - 1807, moved with Sarah to Philadelphia - 1809, became an American citizen and then departed for England to study painting for about nine months with Benjamin West - 1812, elected to honorary membership to the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art; served on its board from -

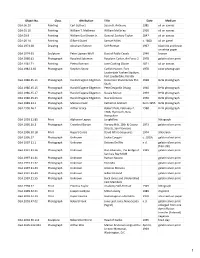

1 Object No. Class. Attribution Title Date Medium CGA.00.10 Painting

Object No. Class. Attribution Title Date Medium CGA.00.10 Painting Carl Gutherz Susan B. Anthony 1985 oil on canvas CGA.01.10 Painting William T. Mathews William McKinley 1900 oil on canvas CGA.03.9 Painting William Garl Brown Jr. General Zachary Taylor 1847 oil on canvas CGA.09.14 Painting Gilbert Stuart Samuel Miles c. 1800 oil on panel CGA.1974.28 Drawing Abraham Rattner Self-Portrait 1967 black ink and brush on white paper CGA.1974.63 Sculpture Peter Lipman-Wulf Bust of Pablo Casals 1946 bronze CGA.1980.61 Photograph Rosalind Solomon Rosalynn Carter, Air Force 2 1978 gelatin silver print CGA.1981.71 Painting Pietro Bonnani Jane Cocking Glover 1821 oil on canvas CGA.1982.3.60 Photograph Stephen Shore Catfish Hunter, Fort 1978 color photograph Lauderdale Yankee Stadium, Fort Lauderdale, Florida CGA.1986.45.11 Photograph Harold Eugene Edgerton Densmore Shute Bends The 1938 B+W photograph Shaft CGA.1986.45.15 Photograph Harold Eugene Edgerton Pete Desjardin Diving 1940 B+W photograph CGA.1986.45.17 Photograph Harold Eugene Edgerton Gussie Moran 1949 B+W photograph CGA.1986.45.23 Photograph Harold Eugene Edgerton Gus Solomons 1960 B+W photograph CGA.1989.13.1 Photograph Mariana Cook Katharine Graham born 1955 B+W photograph CGA.1990.16.2 Photograph Arthur Grace Robert Dole, February 2, 1988 B+W photograph 1988, Plymouth, New Hampshire CGA.1993.11.85 Print Alphonse Legros Longfellow lithograph CGA.1995.10.3 Photograph Crawford Barton Harvey Milk, 18th & Castro 1973 gelatin silver print Streets, San Francisco CGA.1996.50.18 Print Rupert Garcia David Alfaro Sequeiros 1974 silkscreen CGA.1996.57 Photograph Unknown Jackie Coogan c. -

The Notebook of Bass Otis, Philadelphia Portrait Painter

The Notebook of Bass Otis, Philadelphia Portrait Painter THOMAS KNOLES INTRODUCTION N 1931, Charles H. Taylor, Jr., gave the American Antiquarian Society a small volume containing notes and sketches made I by Bass Otis (1784-1 S6i).' Taylor, an avid collector of Amer- ican engravings and lithographs who gave thousands of prints to the Society, was likely most interested in Otis as the man generally credited with producing the first lithographs made in America. But to think of Otis primarily in such terms may lead one to under- estimate his scope and productivity as an artist, for Otis worked in a wide variety of media and painted a large number of portraits in the course of a significant career which spanned the period between 1812 and 1861. The small notebook at the Society contains a varied assortment of material with dated entries ranging from 1815 to [H54. It includes scattered names and addresses, notes on a variety of sub- jects, newspaper clippings, sketches for portraits, and even pages on which Otis wiped off his paint brush. However, Otis also used the notebook as an account book, recording there the business side of his life as an artist. These accounts are a uniquely important source of information about Otis's work. Because Otis was a prohfic painter who left many of his works unsigned, his accounts have been I. The notebook is in the Manuscripts Department, American Andquarian Society. THOMAS KNOLES is curator of manuscripts at the American Andquarian Society. Copyright © i<^j3 by American Andquarian Society Í79 Fig. I. Bass Otis (i7«4-iH6i), Self Portrait, iHfio, oil on tin, y'/z x f/i inches.