Guidebook for Fieldtrips in Connecticut and Massachusetts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Triassic- Jurassic Stratigraphy Of

Triassic- Jurassic Stratigraphy of the <JF C7 JL / Culpfeper and B arbour sville Basins, VirginiaC7 and Maryland/ ll.S. PAPER Triassic-Jurassic Stratigraphy of the Culpeper and Barboursville Basins, Virginia and Maryland By K.Y. LEE and AJ. FROELICH U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 1472 A clarification of the Triassic--Jurassic stratigraphic sequences, sedimentation, and depositional environments UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON: 1989 DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR MANUEL LUJAN, Jr., Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Dallas L. Peck, Director Any use of trade, product, or firm names in this publication is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Lee, K.Y. Triassic-Jurassic stratigraphy of the Culpeper and Barboursville basins, Virginia and Maryland. (U.S. Geological Survey professional paper ; 1472) Bibliography: p. Supt. of Docs. no. : I 19.16:1472 1. Geology, Stratigraphic Triassic. 2. Geology, Stratigraphic Jurassic. 3. Geology Culpeper Basin (Va. and Md.) 4. Geology Virginia Barboursville Basin. I. Froelich, A.J. (Albert Joseph), 1929- II. Title. III. Series. QE676.L44 1989 551.7'62'09755 87-600318 For sale by the Books and Open-File Reports Section, U.S. Geological Survey, Federal Center, Box 25425, Denver, CO 80225 CONTENTS Page Page Abstract.......................................................................................................... 1 Stratigraphy Continued Introduction... .......................................................................................... -

Virginia Horse Shows Association, Inc

2 VIRGINIA HORSE SHOWS ASSOCIATION, INC. OFFICERS Walter J. Lee………………………………President Oliver Brown… …………………….Vice President Wendy Mathews…...…….……………....Treasurer Nancy Peterson……..…………………….Secretary Angela Mauck………...…….....Executive Secretary MAILING ADDRESS 400 Rosedale Court, Suite 100 ~ Warrenton, Virginia 20186 (540) 349-0910 ~ Fax: (540) 349-0094 Website: www.vhsa.com E-mail: [email protected] 3 VHSA Official Sponsors Thank you to our Official Sponsors for their continued support of the Virginia Horse Shows Association www.mjhorsetransportation.com www.antares-sellier.com www.theclotheshorse.com www.platinumjumps.com www.equijet.com www.werideemo.com www.LMBoots.com www.vhib.org 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS Officers ..................................................................................3 Official Sponsors ...................................................................4 Dedication Page .....................................................................7 Memorial Pages .............................................................. 8~18 President’s Page ..................................................................19 Board of Directors ...............................................................20 Committees ................................................................... 24~35 2021 Regular Program Horse Show Calendar ............. 40~43 2021 Associate Program Horse Show Calendar .......... 46~60 VHSA Special Awards .................................................. 63-65 VHSA Award Photos .................................................. -

The Moenave Formation: Sedimentologic and Stratigraphic Context of the Triassic–Jurassic Boundary in the Four Corners Area, Southwestern U.S.A

Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 244 (2007) 111–125 www.elsevier.com/locate/palaeo The Moenave Formation: Sedimentologic and stratigraphic context of the Triassic–Jurassic boundary in the Four Corners area, southwestern U.S.A. ⁎ Lawrence H. Tanner a, , Spencer G. Lucas b a Department of Biology, Le Moyne College, 1419 Salt Springs Road, Syracuse, NY 13214, USA b New Mexico Museum of Natural History, 1801 Mountain Road, N.W., Albuquerque, NM 87104, USA Received 20 February 2005; accepted 20 June 2006 Abstract The Moenave Formation was deposited during latest Triassic to earliest Jurassic time in a mosaic of fluvial, lacustrine, and eolian subenvironments. Ephemeral streams that flowed north-northwest (relative to modern geographic position) deposited single- and multi-storeyed trough cross-bedded sands on an open floodplain. Sheet flow deposited mainly silt across broad interchannel flats. Perennial lakes, in which mud, silt and carbonate were deposited, formed on the terminal floodplain; these deposits experienced episodic desiccation. Winds that blew dominantly east to south-southeast formed migrating dunes and sand sheets that were covered by low-amplitude ripples. The facies distribution varies greatly across the outcrop belt. The lacustrine facies of the terminal floodplain are limited to the northern part of the study area. In a southward direction along the outcrop belt (along the Echo Cliffs and Ward Terrace in Arizona), dominantly fluvial–lacustrine and subordinate eolian facies grade mainly to eolian dune and interdune facies. This transition records the encroachment of the Wingate erg. Moenave outcrops expose a north–south lithofacies gradient from distal, (erg margin) to proximal (erg interior). The presence of ephemeral stream and lake deposits, abundant burrowing and vegetative activity, and the general lack of strongly developed aridisols or evaporites suggest a climate that was seasonally arid both before and during deposition of the Moenave and the laterally equivalent Wingate Sandstone. -

Bioscienceenterprisezone 700.Pdf

J U B E N LITTLE LEAGUE FIELDS SS IP R E E I X C Farmington River State Access Area R Second Natural Pond Last Natural Pond C V K T D A T R Y C D A Y N R R R S E WBER C A D D L R O I D D R R O U A O I R W D N T R N G S D R T T O V R A E D G D Y E R R N R C H ROM D I O L A D T R F D U D B E R W X E D N L E I R O Y O D I R R W N R V D O A R D M D L R R D N N R I E A E A I L Z T R G M A R Y N B R G A W Great Brook E N W A FARM BUILDING E E F R I G E N D F N E D O E I T R GR T N DR W R R L TO U G U O N B A N R I T D W H N T KE B X Poplar Swamp Brook NT R I L O AI S A W LE V Y D I G R C LL L T AG E G TUNXIS MEAD PARK E N N E I A R G P S L E M N 460301 S O I U A D N T R T A N ARKIN IN U L S W O AY L T A M D D O F R EN R WICK K E A D W R L O E L WHIT I T A V L R C N E O O T T T L A D N W O M T O R C O D H C U O E R R D N F P TUNXIS MEAD PARK S D T P E O A R RK R Great Brook M A I I L P N NE R T W D E S RE R M O D F Great Brook E D R S D TUNXIS MEAD PARK A T E M TOWN OF FARMINGTON R Pope Brook E S H D I O X Great Brook A N K U A H T IL L R HARTFORD COUNTY, R D TF L B RD P UN HILL E GALOW V A D TUNXIS MEAD PARK RD N HILL T O L VINE T CONNECTICUT E A G O I CT N BYRNE L I F M C R E OAK ESC FA O LA R N ND A R EN T V C T E T A 0 B P V G E 1 L D ¬« E RD EN PHEASANT HILL C H R S D M T APLE A South Reservoir V-FARM Oakland Gardens DG South Reservoir Dam R I E R D OAKLAND GARDENS FIRE STATION BIOSCIENCE A IL RD R L A GE D O U T E E ID IMBE LI N N Q R V E R L South Reservoir A T T R N O ES I C ER A R L ENTERPRISE ZONE V T A A O A T I U I D L D T O R N N R D R R B N D H L A I G T I L R C W L L D N I D R L I N E L H N D I R O N I H P T N N S S A L U I N U I A D T M A N S D I T R R T D N S U E SEWER TREATMENT PLANT S S R O O T D F . -

Giuffrida Park

Giuffrida Park Directions and Parking: Giuffrida Park was originally part of an area farmed in To get to Giuffrida Park, travel along I-91 either north or the late 1600’s and early 1700’s by Jonathan Gilbert and south. Take Exit 20 and proceed west (left off exit from later Captain Andrew Belcher. This farm, the first European north or left, then right from the south) onto Country Club settlement in this region, became known as the “Meriden Road. The Park entrance is on the right. Parking areas are Farm”, from which the whole area eventually took its name. readily available at the Park. Trails start at the Crescent Today, the Park contains 598 acres for passive recreation Lake parking lot. and is adjacent to the Meriden Municipal Golf Course. Permitted/Prohibited Activities: Located in the northeast corner of Meriden, the trails connect to the Mattabessett Trail (a Connecticut Blue-Blazed Trail) Hiking and biking are permitted. Picnic tables are also and are open to the general public. The trails have easy available. Crescent Lake is a reserve water supply terrain particularly around the Crescent Lake shore with therefore, swimming, rock climbing, and boating are steeper areas along the trap rock ridges ascent of the prohibited. Fishing is also prohibited. Metacomet Ridge and approaching Mt. Lamentation. Mount Lamentation was named in 1636 when a member of Wethersfield Colony became lost and was found by a search party three days later on this ridge, twelve miles from home. There is some controversy whether the Lamentation refers to his behavior or that of those looking for him. -

(King Philip's War), 1675-1676 Dissertation Presented in Partial

Connecticut Unscathed: Victory in The Great Narragansett War (King Philip’s War), 1675-1676 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Major Jason W. Warren, M.A. Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2011 Dissertation Committee: John F. Guilmartin Jr., Advisor Alan Gallay, Kristen Gremillion Peter Mansoor, Geoffrey Parker Copyright by Jason W. Warren 2011 Abstract King Philip’s War (1675-1676) was one of the bloodiest per capita in American history. Although hostile native groups damaged much of New England, Connecticut emerged unscathed from the conflict. Connecticut’s role has been obscured by historians’ focus on the disasters in the other colonies as well as a misplaced emphasis on “King Philip,” a chief sachem of the Wampanoag groups. Although Philip formed the initial hostile coalition and served as an important leader, he was later overshadowed by other sachems of stronger native groups such as the Narragansetts. Viewing the conflict through the lens of a ‘Great Narragansett War’ brings Connecticut’s role more clearly into focus, and indeed enables a more accurate narrative for the conflict. Connecticut achieved success where other colonies failed by establishing a policy of moderation towards the native groups living within its borders. This relationship set the stage for successful military operations. Local native groups, whether allied or neutral did not assist hostile Indians, denying them the critical intelligence necessary to coordinate attacks on Connecticut towns. The English colonists convinced allied Mohegan, Pequot, and Western Niantic warriors to support their military operations, giving Connecticut forces a decisive advantage in the field. -

Perennial Lakes As an Environmental Control on Theropod Movement in the Jurassic of the Hartford Basin

geosciences Article Perennial Lakes as an Environmental Control on Theropod Movement in the Jurassic of the Hartford Basin Patrick R. Getty 1,*, Christopher Aucoin 2, Nathaniel Fox 3, Aaron Judge 4, Laurel Hardy 5 and Andrew M. Bush 1,6 1 Center for Integrative Geosciences, University of Connecticut, 354 Mansfield Road, U-1045, Storrs, CT 06269, USA 2 Department of Geology, University of Cincinnati, 500 Geology Physics Building, P.O. Box 210013, Cincinnati, OH 45221, USA; [email protected] 3 Environmental Systems Graduate Group, University of California, 5200 North Lake Road, Merced, CA 95340, USA; [email protected] 4 14 Carleton Street, South Hadley, MA 01075, USA; [email protected] 5 1476 Poquonock Avenue, Windsor, CT 06095, USA; [email protected] 6 Department of Evolutionary Biology, University of Connecticut, 75 North Eagleville Road, U-3403, Storrs, CT 06269, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-413-348-6288 Academic Editors: Neil Donald Lewis Clark and Jesús Martínez Frías Received: 2 February 2017; Accepted: 14 March 2017; Published: 18 March 2017 Abstract: Eubrontes giganteus is a common ichnospecies of large dinosaur track in the Early Jurassic rocks of the Hartford and Deerfield basins in Connecticut and Massachusetts, USA. It has been proposed that the trackmaker was gregarious based on parallel trackways at a site in Massachusetts known as Dinosaur Footprint Reservation (DFR). The gregariousness hypothesis is not without its problems, however, since parallelism can be caused by barriers that direct animal travel. We tested the gregariousness hypothesis by examining the orientations of trackways at five sites representing permanent and ephemeral lacustrine environments. -

Environmental Review Record

FINAL Environmental Assessment (24 CFR Part 58) Project Identification: Meriden Mills Apartments Disposition and Related Parcel Assembly Meriden, CT Map/Lots: 0106-0029-0001-0003 0106-0029-0002-0000 0106-0029-001A-0000 Responsible Entity: City of Meriden, CT Month/Year: March 2017 Meriden Mills Apartments Disposition and Related Parcel Assembly, City of Meriden, CT Environmental Assessment Determinations and Compliance Findings for HUD-assisted Projects 24 CFR Part 58 Project Information Responsible Entity: City of Meriden, CT [24 CFR 58.2(a)(7)] Certifying Officer: City Manager, Meriden, CT [24 CFR 58.2(a)(2)] Project Name: Meriden Commons Project Location: 144 Mills Street, 161 State Street, 177 State Street, 62 Cedar Street; Meriden CT. Estimated total project cost: TBD Grant Recipient: Meriden Housing Authority, Meriden CT. [24 CFR 58.2(a)(5)] Recipient Address: 22 Church Street Meriden, CT 06451 Project Representative: Robert Cappelletti Telephone Number: 203-235-0157 Conditions for Approval: (List all mitigation measures adopted by the responsible entity to eliminate or minimize adverse environmental impacts. These conditions must be included in project contracts or other relevant documents as requirements). [24 CFR 58.40(d), 40 CFR 1505.2(c)] The proposed action requires no mitigation measures. 2 4/11/2017 4/11/2017 Meriden Mills Apartments Disposition and Related Parcel Assembly, City of Meriden, CT This page intentionally left blank. 4 Meriden Mills Apartments Disposition and Related Parcel Assembly, City of Meriden, CT Statement of Purpose and Need for the Proposal: [40 CFR 1508.9(b)] This Environmental Assessment (EA) is a revision of the Final EA for Meriden Mills Apartments Disposition and Related Parcel Assembly prepared for the City of Meriden (“the City”) in October 2013. -

Municipal Plan and Regulation Review, the Committee Provided Municipal Land Use Regulations and Pcds for Most of the Participating Towns

MUNICIPAL PLAN & REGULATION REVIEW LOWER FARMINGTON RIVER & SALMON BROOK WILD AND SCENIC STUDY COMMITTEE March 2009 Avon Bloomfield Burlington Canton East Granby Farmington Granby Hartland Simsbury Windsor Courtesy of FRWA MUNICIPAL PLAN & REGULATION REVIEW LOWER FARMINGTON RIVER & SALMON BROOK WILD AND SCENIC STUDY COMMITTEE MARCH 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS • EXECUTIVE SUMMARY • INTRODUCTION • PROJECT OVERVIEW AND METHODOLOGY • STATUTORY FRAMEWORK • DEFINITIONS & ACRONYMS • STUDY CORRIDOR SUMMARY • TOWN SUMMARIES o Avon o Bloomfield o Burlington o Canton o East Granby o Farmington o Granby o Hartland o Simsbury o Windsor • REVIEW CHART o Geology o Water Quality o Biodiversity o Recreation o Cultural Landscape o Land Use EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The proposed designation of the lower Farmington River and Salmon Brook as a Wild and Scenic River, pursuant to 16 U.S.C. §§ 1271 to 1287 (2008), is a regional effort to recognize and protect the River itself and its role as critical habitat for flora and fauna, as a natural flood control mechanism, and as an increasingly significant open space and recreational resource. A review of the municipal land use regulations and Plans of Conservation and Development (“PCD”) for the ten towns bordering the River within the Lower Farmington and Salmon Brook Watersheds (the “Corridor Towns”) was conducted (the “Review”). The results of the Review identify and characterize the level of protection established in local regulations for each of the six different Outstanding Resource Values (“ORVs”), or natural, cultural, or recreational values of regional or national significance associated with the Lower Farmington River and Salmon Brook. Designation of the Lower Farmington River and Salmon Brook as Wild and Scenic will not impact existing land use plans and regulations in the ten Corridor Towns. -

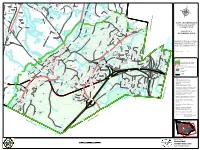

AQUIFERPROTECTIONAREA SP Lainville

d n H L Bradley Brook Beaverdam Pond Williams Pond r r R u D H r D s D t d Taine and y ell S 4 d Mountain c 7 Upl nd xw rn e Rd a a e 6 n i m M F n SV k 1 t L l or t n R s r s n o l N a Morley Elementary School R H l y Fisher Meadows gg s E N ! e L w Pi u e r H b a o b r S m d r n ld D W R e l b k D O'Larrys Ice Pond No 1 t o el c T e e r r A r o e a w a R a Ratlum Mountain Fish & Game Club Pond i t x y a Edward W Morley School u r f S r d r M t h r A 162 a d v D r l h a i i n h l r d R o v s y Charles W House u n R L C l u A o n l P l a o r Av ry l ll n e t i e d a n M M D w r n R n i e m k H L c D S e d Farmington Woods 2 H e B 4 v t o n d R R o o l a r i S i d Fisher Meadows e n a C e n l B 167 p V o M S r i l e lton St D r A A 133 F l V l r r o D u i S e C V i M n v s l l R o S e r D u v B e H b u o D y T H y A 156 A A e o q l ob n l m S e o d S i e t i e t A 162 r S n S r i o s n r n o v r d H R e l i u t s ar Av Punch Brook n r l b a h t e n r v c rm l s e e r Trout Brook R h o o D S c b n i O e a d l e R e l r v m o k l e L t A r t s d W s r i n s d r r West Hartford Reservoir No 5 a o l a R f o C d o r R tm d r e r S f i d o h i W o o i y Taine Mountain W v D e a t s n l a u t d R n i l W L e k r f v l r y A V O N Dyke Pond D D L a b r t e d W B e L l n o a r R o y t A R a n y i S g r d a r Punch Brook Ponds J n g y e i o d M a d B S d r B n a d e t a a y A s i i n b o H E r P d t G L e c r r d L r t R w il n y v d n o e f l a il H A P x r e t u e i n m nc M t l i w h B P e t e l R e r e a i S R o Norw s ! o ood Rd t d Bayberry -

The Horse-Breeder's Guide and Hand Book

LIBRAKT UNIVERSITY^' PENNSYLVANIA FAIRMAN ROGERS COLLECTION ON HORSEMANSHIP (fop^ U Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2009 with funding from Lyrasis IVIembers and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/horsebreedersguiOObruc TSIE HORSE-BREEDER'S GUIDE HAND BOOK. EMBRACING ONE HUNDRED TABULATED PEDIGREES OF THE PRIN- CIPAL SIRES, WITH FULL PERFORMANCES OF EACH AND BEST OF THEIR GET, COVERING THE SEASON OF 1883, WITH A FEW OF THE DISTINGUISHED DEAD ONES. By S. D. BRUCE, A.i3.th.or of tlie Ainerican. Stud Boole. PUBLISHED AT Office op TURF, FIELD AND FARM, o9 & 41 Park Row. 1883. NEW BOLTON CSNT&R Co 2, Entered, according to Act of Congress, in the year 1883, By S. D. Bruce, In the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington, D. C. INDEX c^ Stallions Covering in 1SS3, ^.^ WHOSE PEDIGREES AND PERFORMANCES, &c., ARE GIVEN IN THIS WORK, ALPHABETICALLY ARRANGED, PAGES 1 TO 181, INCLUSIVE. PART SECOISTD. DEAD SIRES WHOSE PEDIGREES AND PERFORMANCES, &c., ARE GIVEN IN THIS WORK, PAGES 184 TO 205, INCLUSIVE, ALPHA- BETICALLY ARRANGED. Index to Sires of Stallions described and tabulated in tliis volume. PAGE. Abd-el-Kader Sire of Algerine 5 Adventurer Blythwood 23 Alarm Himvar 75 Artillery Kyrle Daly 97 Australian Baden Baden 11 Fellowcraft 47 Han-v O'Fallon 71 Spendthrift 147 Springbok 149 Wilful 177 Wildidle 179 Beadsman Saxon 143 Bel Demonio. Fechter 45 Billet Elias Lawrence ' 37 Volturno 171 Blair Athol. Glen Athol 53 Highlander 73 Stonehege 151 Bonnie Scotland Bramble 25 Luke Blackburn 109 Plenipo 129 Boston Lexington 199 Breadalbane. Ill-Used 85 Citadel Gleuelg... -

) Baieiicanjizseum

)SovitatesbAieiicanJizseum PUBLISHED BY THE AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY CENTRAL PARK WEST AT 79TH STREET, NEW YORK 24, N.Y. NUMBER 1901 JULY 22, 1958 Coelurosaur Bone Casts from the Con- necticut Valley Triassic BY EDWIN HARRIS COLBERT1 AND DONALD BAIRD2 INTRODUCTION An additional record of a coelurosaurian dinosaur in the uppermost Triassic of the Connecticut River Valley is provided by a block of sandstone bearing the natural casts of a pubis, tibia, and ribs. This specimen, collected nearly a century ago but hitherto unstudied, was brought to light by the junior author among the collections (at present in dead storage) of the Boston Society of Natural History. We are much indebted to Mr. Bradford Washburn and Mr. Chan W. Wald- ron, Jr., of the Boston Museum of Science for their assistance in mak- ing this material available for study. The source and history of this block of stone are revealed in brief notices published at the time of its discovery. The Proceedings of the Boston Society of Natural History (vol. 10, p. 42) record that on June 1, 1864, Prof. William B. Rogers "presented an original cast in sand- stone of bones from the Mesozoic rocks of Middlebury, Ct. The stone was probably the same as that used in the construction of the Society's Museum; it was found at Newport among the stones used in the erec- tion of Fort Adams, and he owed his possession of it to the kindness of Capt. Cullum." S. H. Scudder, custodian of the museum, listed the 1 Curator of Fossil Reptiles and Amphibians, the American Museum of Natural History.