Ubaldo Inspired by Challenging Upbringing Veteran Righty Motivated

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A's News Clips, Thursday, March 3, 2011 A's Outfielder Coco Crisp

A’s News Clips, Thursday, March 3, 2011 A's outfielder Coco Crisp arrested on suspicion of DUI By Joe Stiglich Oakland Tribune A's center fielder Coco Crisp was arrested on suspicion of driving under the influence of alcohol early Wednesday morning, according to an A's news release. Crisp was detained and taken to City of Scottsdale Jail before being released Wednesday morning. He showed up to Phoenix Municipal Stadium on time to join the team for pre-game drills and was in uniform -- but not in the lineup -- for a game against the Cleveland Indians. Crisp declined to comment when asked about the situation, saying he would address the media "in due time." "The A's are aware of the situation and take such matters seriously," the A's statement read. "The team and Coco will have no further comment until further details are available." Crisp, 31, is in his second season with the A's and is slated to play center field and be the leadoff hitter. Ironically, the A's held a security meeting with Major League Baseball officials before taking the field Wednesday. A message that is stressed in the annual meeting is having awareness of the off-field dangers that exist for professional athletes. Crisp signed with the A's as a free agent in December 2009. He hit .279 with eight homers and 38 RBIs last season but played in just 75 games because of a fractured pinkie and strained rib cage muscle. Crisp posts frequently on his Twitter account and often makes reference to his nighttime socializing. -

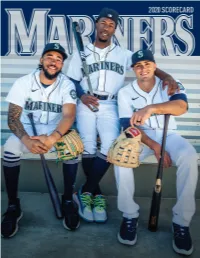

Play Ball in Style

Manager: Scott Servais (9) NUMERICAL ROSTER 2 Tom Murphy C 3 J.P. Crawford INF 4 Shed Long Jr. INF 5 Jake Bauers INF 6 Perry Hill COACH 7 Marco Gonzales LHP 9 Scott Servais MANAGER 10 Jarred Kelenic OF 13 Abraham Toro INF 14 Manny Acta COACH 15 Kyle Seager INF 16 Drew Steckenrider RHP 17 Mitch Haniger OF 18 Yusei Kikuchi LHP 21 Tim Laker COACH 22 Luis Torrens C 23 Ty France INF 25 Dylan Moore INF 27 Matt Andriese RHP 28 Jake Fraley OF 29 Cal Raleigh C 31 Tyler Anderson LHP 32 Pete Woodworth COACH 33 Justus Sheffield LHP 36 Logan Gilbert RHP 37 Paul Sewald RHP 38 Anthony Misiewicz LHP 39 Carson Vitale COACH 40 Wyatt Mills RHP 43 Joe Smith RHP 48 Jared Sandberg COACH 50 Erik Swanson RHP 55 Yohan Ramirez RHP 63 Diego Castillo RHP 66 Fleming Baez COACH 77 Chris Flexen RHP 79 Trent Blank COACH 88 Jarret DeHart COACH 89 Nasusel Cabrera COACH 99 Keynan Middleton RHP SEATTLE MARINERS ROSTER NO. PITCHERS (14) B-T HT. WT. BORN BIRTHPLACE 31 Tyler Anderson L-L 6-2 213 12/30/89 Las Vegas, NV 27 Matt Andriese R-R 6-2 215 08/28/89 Redlands, CA 63 Diego Castillo (IL) R-R 6-3 250 01/18/94 Cabrera, DR 77 Chris Flexen R-R 6-3 230 07/01/94 Newark, CA PLAY BALL IN STYLE. 36 Logan Gilbert R-R 6-6 225 05/05/97 Apopka, FL MARINERS SUITES PROVIDE THE PERFECT 7 Marco Gonzales L-L 6-1 199 02/16/92 Fort Collins, CO 18 Yusei Kikuchi L-L 6-0 200 06/17/91 Morioka, Japan SETTING FOR YOUR NEXT EVENT. -

LEESVOER 27 Juni 2020 Nr

LEESVOER 27 juni 2020 Nr. 1 1 EDITOR-IN-CHIEF EINDREDACTIE REDACTIE VORMGEVING FOTOGRAFIE Marco Stoovelaar Jasper Roos Feiko Drost Jasper Roos Robert Bos Coen Stoovelaar Renata Jansen Györgyike Horvath honkbalweek @honkbalweek honkbalweek honkbalweek www.honkbalweek.nl Welkom... ...in deze eerste speciale editie van Leesvoer. Het is vandaag Snik! zaterdag 27 juni 2020. De eerste speeldag van de 30e Honkbalweek Haarlem stond voor gisteren op het programma Ook dit jaar zou Feiko Drost ondermeer de openingstekst en zou gezien de weersomstandigheden probleemloos zijn maken, zou eindredacteur Jasper Roos de wedstrijdverslagen afgewerkt. Maar er is helaas geen Honkbalweek Haarlem in en lay-out/opmaak weer voor zijn rekening nemen, zou 2020. De reden hiervoor weten we natuurlijk allemaal en de Györgyike Horvath weer vragen voorleggen aan spelers en beslissing om in eind maart de streep door het evenement te medewerkers, zou Coen Stoovelaar wederom aanvullende zetten was de enige juiste. informatie leveren en zou ‘editor-in-chief’ Marco Stoovelaar de redactiegroep weer hebben gepoogd in het gareel te Het redactieteam van Leesvoer was ook dit keer weer van houden (en voor de nodige historische verhalen en grote plan tien dagen lang een lezenswaardig dag-bulletin te achtergrondverhalen/interviews in het Leesvoer hebben creëren. Net als twee jaar geleden een digitale versie die via getekend). Samen zouden we weer de korte berichten hebben de website van de Honkbalweek te downloaden was. Maar verzameld en (soms) verzonnen voor de rubriek Hit & Run vrijwel zeker zou er dit keer ook weer een papieren versie zijn en fotograaf Robert Bos had ongetwijfeld weer voor mooie geweest. -

Port Aransas

Inside the Moon Kite Day A2 Island Spring A4 Botanical Gardens A7 Fishing A11 Remember When A16 Issue 829 The 27° 37' 0.5952'' N | 97° 13' 21.4068'' W Island Free The voiceMoon of The Island since 1996 March 5, 2020 Weekly www.islandmoon.com FREE Around Island Grocery Store Waterpark How the Island Voted The Island Going Up! Ride Nueces County Constable By Dale Rankin Precinct 4 (Runoff) Once upon a time on a beach not so Set to open by summer 2020 1123 (45%) Monty Allen far away Spring Breakers swarmed to Comes 1101 (44%) Robert Sherwood the beach north of Packery Channel By Dale Rankin space. Mr. Rasheed said a verbal between Zahn Road and Newport agreement has been reached to locate 269 (10.8%) John Bowers The 20,420 square-foot IGA grocery Pass. Cheek to jowl they lined the a Denny’s diner on a separate three- store under construction on South Down Padre Island totals beach with tents, couches, giant thousand square-foot site fronting Padre Island Drive south of Whitecap bonfires, and bags of trash, most of SPID. 7882 Total Padre Island which got left behind when they went Boulevard will be open by summer Registered Voters home. 2020, according to owners Lori and Mr. Rasheed said the IGA store will Moshin Rasheed. be roughly based on the design of a 2510 (32%) Total Padre Island Police flooded the area but to little Sprouts Farmer’s Market and will voters “We will have the equipment for avail as the revelers, very few of include walk-in coolers for produce the grocery store arriving in the Contested Races Republican which were actual college students, and meat with a butcher on duty, a next few weeks,” Mr. -

LEVELAND INDIANS 2012 OFFICIAL GAME INFORMATION CLEVELAND INDIANS (52-61, 3Rd, -10.0G) Vs

LEVELAND INDIANS 2012 OFFICIAL GAME INFORMATION CLEVELAND INDIANS (52-61, 3rd, -10.0G) vs. BOSTON RED SOX (56-58) RHP Zach McAllister (4-4, 3.60) vs. LHP Franklin Morales (3-2, 3.14) Game #114/Home #58 » Sat., Aug. 11, 2012 » Progressive Field » 6:05 p.m. (ET) » STO/WTAM/Indians Radio Network UPCOMING PROBABLES & BROADCAST INFORMATION Date Opponent Probable Pitchers - Cleveland vs. Opponent First Pitch TV/Radio Sun., August 12 vs. Boston RHP Corey Kluber (0-0, 6.10) vs. LHP Jon Lester (5-10, 5.36) 1:05PM ET STO/WTAM/IRN Mon., August 13 at Los Angeles-AL RHP Justin Masterson (8-10, 4.68) vs. LHP C.J. Wilson (9-8, 3.34) 10:05PM ET STO/WTAM/IRN Tues., August 14 at Los Angeles-AL RHP Ubaldo Jimenez (9-11, 5.25) vs. RHP Zack Greinke (0-1, 5.68) 10:05PM ET STO/WTAM/IRN Wed., August 15 at Los Angeles-AL TBD vs. RHP Ervin Santana (5-10, 5.82) 10:05PM ET STO/WTAM/IRN THE STANDINGS: The Indians lost to the Red Sox 3-2 last night, falling SET-EM-UP, KNOCK-EM-DOWN: VINNIE PESTANO has an active score- 10.0 games behind Chicago in the A.L. Central standings...the Tribe less streak of 21.0 consecutive innings, the longest by any Indians pitcher is also 9.0 games back in the A.L. Wild Card standings...Cleveland has this season and longest by a Tribe reliever since PAUL ASSENMACHER been in 3rd place for 27 straight days after spending 56 consecutive days strung together 23.1 shutout frames from June 18-August 26, 1997...Pes- in either first or 2nd place (April 24-July 14)...of the 128 days of the Indians’ tano’s streak is currently the 3rd-longest active streak in the majors behind season, Cleveland has been in first place for 40 days, 2nd place for 46 days Tampa Bay’s J.P. -

2009 Media/Scouts Notes Tuesday, October 13, 2009 Media Relations CONTACTS: Paul Jensen (480/710-8201, [email protected]) Adam C

2009 Media/Scouts Notes Tuesday, October 13, 2009 Media Relations CONTACTS: Paul Jensen (480/710-8201, [email protected]) Adam C. Nichols (843/735-1517, [email protected]) Rob Morse (480/232-1291, [email protected]) Media Relations FAX: 602/681-9363 Website: www.mlbfallball.com Twitter: MLBazFallLeague Eastern Division Team W L Pct. GB Home Away Div. Streak Last 10 Probable Pitchers Mesa Solar Sox 0 0 .000 - 0-0 0-0 0-0 - - October 13, 2009 Phoenix Desert Dogs 0 0 .000 - 0-0 0-0 0-0 - - Surprise at Javelinas, 12:35 PM (A) Scottsdale Scorpions 0 0 .000 - 0-0 0-0 0-0 - - 22 Ian Kennedy (RHP/NYY) 0-0, N/A @ 34 Scot Drucker (RHP/DET) 0-0, N/A Western Division Mesa at Phoenix, 12:35 PM (L) Team W L Pct. GB Home Away Div. Streak Last 10 47 Randor Bierd (RHP/BOS) 0-0, N/A @ Peoria Javelinas 0 0 .000 - 0-0 0-0 0-0 - - 43 Ryohei Tanaka (RHP/BAL) 0-0, N/A Peoria Saguaros 0 0 .000 - 0-0 0-0 0-0 - - Saguaros at Scottsdale, 6:35 PM (F) Surprise Rafters 0 0 .000 - 0-0 0-0 0-0 - - 32 Mike Minor (LHP/ATL) 0-0, N/A @ 49 Joe Martinez (RHP/SF) 0-0, N/A ’09 Fall League “Nuggets” Record Number of 1st-Round Picks: Thirty-six former first-round draft picks will play in the 2009 October 14, 2009 Arizona Fall League. Fourteen – OF Adam Loewen (4th in 2002, BAL), RHP Mark Rogers (5th in 2004, Javelinas at Surprise, 12:35 PM (A) th nd MIL), LHP Andrew Miller (6 in 2006, DET), IF Mike Moustakas (2 in 2007, KC), IF Josh Vitters 31 Justin Cassel (RHP/CWS) 0-0, N/A @ rd th th (3 in 2007, CHC), LHP Danny Moskos (4 in 2007, PIT), C Buster Posey (5 in 2008, SF), IF 34 Jenrry Mejia (RHP/NYM) 0-0, N/A Yonder Alonso (7th in 2008, CIN), C Jason Castro (10th in 2008, HOU), RHP Stephen Strasburg (1st Scottsdale at Saguaros, 12:35 PM (F) in 2009, WSH), OF Dustin Ackley (2nd in 2009, SEA), LHP Mike Minor (7th in 2009, ATL), RHP Mike 56 Donald Veal (LHP/PIT) 0-0, N/A @ th th Leake (8 in 2009, CIN), and RHP Drew Storen (10 in 2009, WSH) – were top 10\ selections. -

Oil Workers' Rights Will Not Be Undermined, Minister Says

SUBSCRIPTION WEDNESDAY, JUNE 22, 2016 RAMADAN 17, 1437 AH www.kuwaittimes.net Alghanim to More than 700 England Iran: Bahrain Ramadan TImings expand Wendy’s doctors killed progress after ‘will pay price’ Emsak: 03:04 brand into Saudi in Syrian war Slovakia draw for crackdown Fajer: 03:14 Shrooq: 04:48 Dohr: 11:50 Asr: 15:24 Maghreb: 18:51 2 7 19 13 Eshaa: 20:23 Oil workers’ rights will not Min 33º Max 47º be undermined, Minister says High Tide 02:55 & 12:12 Low Tide MPs call for new strategy for Kuwaiti investments 06:55 & 19:57 40 PAGES NO: 16912 150 FILS KUWAIT: Finance Minister and Acting Oil Minister Anas Ramadan Kareem Al-Saleh said yesterday the government will not under- mine the rights of the workers in the oil sector who Social dimension went on a three-day strike in April to demand their rights. The minister said that the oil sector proposed a of fasting, Ramadan number of initiatives to cut spending in light of the sharp drop in oil prices and the workers went on strike By Hatem Basha even before these initiatives were applied. ost people view Ramadan as a sublime peri- He said the Ministry is currently in talks with the od, where every Muslim experience sublime workers about the initiatives but insisted that the Mfeelings as hearts soften and souls tran- rights of the workers will not be touched. The minis- scend the worldly pleasures. Another dimension that ter’s comments came in response to remarks made by is often overlooked is the social dimension of fasting. -

Oakland Athletics Virtual Press

OAKLAND ATHLETICS Game Information Oakland Athletics Baseball Company h 7000 Coliseum Way h Oakland, CA 94621 510-638-4900 h Public Relations Facsimile 510-562-1633 h www.oaklandathletics.com YESTERDAY OAKLANDC ATHLETICS (12-15-3) VS. SAN FRANCISCO GIANTS (21-11) The A’s shutout the Giants on five FRIDAY, APRIL 2, 2010 – AT&T PARK – 7:15 P.M. hits in San Francisco, 9-0…Justin Duchscherer started for the A’s and tossed 6.0 innings, allowing three ABOUT THE A’s of the hits and walking two while ABOUT THE A’S: The A’s snapped a five-game winless streak last night and are now 12-15-3 striking out six…Jerry Blevins, (.450)…have clinched a losing record for the second consecutive spring (went 17-18-2 last year)…the last Craig Breslow and Tyson Ross time the A’s finished the spring with a winning percentage under .450 was in 1990 when they went 6-10 pitched one scoreless inning of (.375)…the A’s record is tied for ninth best among the 15 Cactus League teams, but it is the best mark relief each…Kevin Kouzmanoff had among the four American League West teams…have three tie games, which are the A’s most ties during a RBI double in the first inning to the spring since moving to Arizona in 1969…the shutout last night lowered the A’s ERA to 5.62, which is open the scoring and Kurt Suzuki the lowest it has been since the fourth game of the spring (March 8)…however, it is the fourth highest ERA followed with a two-run in the majors…rank third in the majors in most hits (316) and tied for third in most walks (118)…are tied for homer…Rajai Davis and the -

Cincinnati Reds'

CCIINNCCIINNNNAATTII RREEDDSS PPRREESSSS CCLLIIPPPPIINNGGSS MARCH 1,, 2014 THIS DAY IN REDS HISTORY: MARCH 1, 2007 – THE FATHER AND SON DUO, MARTY AND THOM BRENNAMAN, CALLED THEIR FIRST REDS GAME AS BROADCAST PARTNERS ON 700 WLW. THE TWO WORKED TOGETHER ONCE BEFORE ON A CUBS-REDS GAME IN THE EARLY 1990S FOR THE BASEBALL NETWORK. THEY BECAME THE FOURTH FATHER SON BROADCAST TEAM IN MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL (JOE AND JOHN BUCK, HARRY, SKIP AND CHIP CARAY AND HARRY AND TODD KALAS). CINCINNATI ENQUIRER Intensity is always Tony Cingrani's specialty Cingrani has one speed, and that's going all out By C. Trent Rosecrans GOODYEAR, ARIZ. — Tony Cingrani gets angry every time he gives up a hit. It doesn’t matter if it’s a spring training exhibition game – like the one he will start Saturday against the Colorado Rockies – or against the St. Louis Cardinals. As the Reds’ second-year starter sees it, it’s his job to not give up any hits and if he gives up a hit, he didn’t do his job. That makes him angry – and like a famous fictional character, you wouldn’t like him when he’s angry. “That’s how I get myself fired up. I need to throw harder, so I try to get super angry and throw it harder,” Cingrani said. “I’m not turning green – I’m trying to scare somebody and see what happens.” Cingrani’s intensity even turned into a meme among Reds fans, with the “Cingrani Face” becoming synonymous with an intense, scary mug. Cingrani said he saw that, and even chuckles quietly about it. -

0908 Giants.Pdf

Manager: Scott Servais (29) NUMERICAL ROSTER 1 Kyle Lewis OF 3 J.P. Crawford INF 4 Shed Long Jr. INF 6 Yoshihisa Hirano RHP 7 Marco Gonzales LHP 9 Dee Strange-Gordon INF/OF 12 Evan White INF 13 Perry Hill COACH 14 Manny Acta COACH 15 Kyle Seager INF 18 Yusei Kikuchi LHP 20 Phillip Ervin OF 21 Tim Laker COACH 22 Luis Torrens C 23 Ty France INF 25 Dylan Moore INF/OF 26 José Marmolejos INF 27 Joe Thurston COACH 28 Sam Haggerty INF 29 Scott Servais MANAGER 32 Pete Woodworth COACH 33 Justus Sheffield LHP 35 Justin Dunn RHP 37 Casey Sadler RHP 38 Anthony Misiewicz LHP 39 Carson Vitale COACH 40 Brian DeLunas COACH 44 Jarret DeHart COACH 48 Jared Sandberg COACH 49 Kendall Graveman RHP 50 Erik Swanson RHP 52 Nick Margevicius LHP 54 Joseph Odom C 55 Yohan Ramirez RHP 59 Joey Gerber RHP 60 Seth Frankoff RHP 62 Brady Lail RHP 65 Brandon Brennan RHP 66 Fleming Báez COACH 73 Walker Lockett RHP 74 Ljay Newsome RHP 81 Aaron Fletcher LHP 89 Nasusel Cabrera COACH SEATTLE MARINERS ROSTER NO. PITCHERS (16) B-T HT. WT. BORN BIRTHPLACE 65 BRENNAN, Brandon (IL) R-R 6-4 220 07/26/91 Mission Viejo, CA 35 DUNN, Justin R-R 6-2 185 09/22/95 Freeport, NY 81 FLETCHER, Aaron L-L 6-0 220 02/26/96 Geneseo, IL 60 FRANKOFF, Seth R-R 6-5 215 08/27/88 Raleigh, NC 59 GERBER, Joey R-R 6-4 215 05/03/97 Maple Grove, MN 7 GONZALES, Marco L-L 6-1 199 02/16/92 Fort Collins, CO 49 GRAVEMAN, Kendall R-R 6-2 200 12/21/90 Alexander City, AL 6 HIRANO, Yoshihisa R-R 6-1 185 03/08/84 Kyoto, Japan 18 KIKUCHI, Yusei L-L 6-0 200 06/17/91 Iwate, Japan 62 LAIL, Brady R-R 6-2 200 08/09/93 South Jordan, UT 73 LOCKETT, Walker R-R 6-5 225 05/03/94 Jacksonville, FL 52 MARGEVICIUS, Nick L-L 6-5 220 06/18/96 Cleveland, OH 38 MISIEWICZ, Anthony R-L 6-1 200 11/01/94 Detroit, MI 74 NEWSOME, Ljay R-R 5-11 210 11/08/96 La Plata, MD 55 RAMIREZ, Yohan R-R 6-4 190 05/06/95 Villa Mella, DR 37 SADLER, Casey R-R 6-3 205 07/13/90 Stillwater, OK 33 SHEFFIELD, Justus L-L 6-0 200 05/13/96 Tullahoma, TN 50 SWANSON, Erik (IL) R-R 6-3 220 09/04/93 Fargo, ND NO. -

2010 Championship Game Notes Saturday, November 20, 2010 Media Relations CONTACTS: Paul Jensen (480/710-8201, [email protected]) Adam C

2010 Championship Game Notes Saturday, November 20, 2010 Media Relations CONTACTS: Paul Jensen (480/710-8201, [email protected]) Adam C. Nichols (617/448-1942, [email protected]) Pat Kurish (480/628-4446, [email protected]) Media Relations FAX: 602/681-9363 Website: www.mlbfallball.com Facebook: www.facebook.com/MLBFallBall Twitter: @MLBazFallLeague Arizona Fall League East Division Team W L Pct. GB Home Away Div. Streak Last 10 AFL Championship History Scottsdale Scorpions 20 12 .625 - 12-3 8-9 8-5 L1 6-4 2009 Phoenix Desert Dogs 4 Mesa Solar Sox 13 17 .433 6.0 8-7 5-10 3-8 L6 3-7 Peoria Javelinas 5 Phoenix Desert Dogs 11 17 .393 7.0 6-8 5-9 7-5 W3 5-5 2008 Mesa Solar Sox 4 Phoenix Desert Dogs 10 Arizona Fall League West Division 2007 Phoenix Desert Dogs 7 Team W L Pct. GB Home Away Div. Streak Last 10 Surprise Rafters 2 Peoria Javelinas 20 10 .667 - 10-5 10-5 8-4 W1 7-3 Surprise Rafters 17 12 .586 2.5 11-5 6-7 9-3 W4 6-4 2006 Grand Canyon Rafters 2 Phoenix Desert Dogs 6 Peoria Saguaros 9 22 .290 11.5 6-9 3-13 1-11 W1 2-8 2005 Surprise Scorpions 2 Phoenix Desert Dogs 6 AFL Championship Game First-Round Draft Picks The Championship Game will feature nine first-round picks between the teams 2004 Scottsdale Scorpions 2 nd 2B Dustin Ackley (SEA) 2 in ’09 Phoenix Desert Dogs 6 RHP Rex Brothers (COL) 34th in ‘09 2003 Mesa Solar Sox 7 OF Mike Burgess (WSH) 49th in ‘07 st Mesa Desert Dogs 2 IF Charlie Culberson (SF) 51 in ‘07 C Ed Easley (ARI) 61st in ‘07 2002 Peoria Javelinas 7 RHP Josh Fields (SEA) 20th in ‘08 Scottsdale Scorpions 1 IF Conor Gillaspie (SF) 37th in ‘08 OF Bryce Harper (WSH) 1st in ‘10 2001 Phoenix Desert Dogs 12 OF A.J. -

Pronk's Homer Punctuates Sweep of Royals by Robert Falkoff / Special

Pronk's homer punctuates sweep of Royals By Robert Falkoff / Special to MLB.com | 4/15/2012 8:20 PM ET KANSAS CITY -- The Indians made a statement with their offense over the weekend and Travis Hafner delivered the symbolic exclamation point. In Cleveland's 13-7 victory over the Royals on Sunday, Hafner launched the most majestic of his team's four homers. Hafner's 456-foot blast to right field in the fifth inning off Luis Mendoza traveled so far that it wound up as a souvenir inside Rivals Sports Bar, which is located high above the wall. No word on whether it came down in somebody's order of chicken wings. It was the first homer to land in the Rivals establishment since Kauffman Stadium was renovated in 2009. In short, Hafner got all of it and then some. "I was able to stay back on an off-speed pitch and backspin it," said Hafner, who finished 3-for-4. "I think there have been some [homers] before that measured in the 470s, but that's about as good as I can hit 'em." Shelley Duncan, Casey Kotchman and Jason Kipnis joined Hafner in the home run parade, as the Indians put up runs in bunches and applied the finishing touches on a three-game sweep. Right-hander Ubaldo Jimenez, making his return from a five-game suspension, labored through five innings, but got the win thanks to robust offensive support. "The first three innings, it was hard to get in a good rhythm," said Jimenez, who refused to use rustiness as an excuse.