Trade Union Membership, 1897-1962

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trade Unions at Work

Publications and further information The TUC publishes a wide range of reports, leaflets, books and DVDs. We also produce a downloadable educational resource pack for schools and youth organisations, A Better Way to Work, to help young people prepare for the world of work. We have an extensive website at www.tuc.org.uk. This contains press statements, campaign news, policy briefings, statistical information and publications for sale. Register online for free email news updates matching your areas of interest. Reprint of revised edition May 2010 4K Design: Eureka! Print: College Hill Press ISBN 978 1 85006 862 4 Contact details: Trades Union Congress Congress House Great Russell Street London WC1B 3LS Tel: 020 7636 4030 Fax: 020 7636 0632 www.tuc.org.uk If you do not belong to a union and want to know which Trade unions one to join, phone the TUC ‘Join a Union’ line on: 0870 600 4882 at work Calls are charged at the national rate. Front cover photo: For more information about the TUC’s different activities what they are and what they do try one of our websites: John Harris/reportdigital.co.uk www.tuc.org.uk (main site) www.worksmart.org.uk (help and advice for everyone at work) www.unionlearn.org.uk (for learners and learning reps) www.unionhistory.info (TUC archives online) Printed on a FSC Certified Product Including a guide to the Trades Union Congress Contents Introduction 03 Introduction: The world of work the world of work 04 Section 1: Unions today 12 Section 2: The TUC 22 Glossary Work dominates modern life. -

Trade Unions and the Capitalist State.Pdf

,/ ~· InzyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBAparticular, texts such as Th~rborn:s, l/7ha/ b Dou /he Rllling Clan DokjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA Unfortunately there has been a tradicional failure amongst Marxists to Ir,mlll UII/U?, and Poul~tzas , S/a/e, POllJer, JOCla/IJIII, expllcltly con- :..:".r-'~~~- address the relationship between trade unionism and the state in a 't"""." rJj; cáhed tfiemselves with tracing and delineating the changing patterns , - I ~ rigorous dialectical fashion. Therborn's valuable perception, for ..,'.~.~<~ of bourgeois-democratic rule In \Ore ff1ollop·6!y==capinrtistera:! The ¡/ 1 instance, that as a collective mass organization, 'the labour movement \ \ si~f1íficantchanges were broadly seen to entail : a s_hiftin the lo¿us 0L isorganized in a fundamentally different way from the state bureaucracyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA dccision-rnakinp from parliament ro the techno:ratic/exec~tive appar- l or a capitalist firm,' was not carried over to examine the contradietions , --l:> atus of tfie state¡ the fus!on of tIle stafeat ~Ievel wHh the top that arise when trade-union represent¡1tives)oin state personnel and echelons of ca )italis..!_s~rise¡ and the gener:1Qre:úilllg...do.wn of the capitalist management in 'institutionahzed Joint bodles' .• For his <7 public-prizate boundaries hat previously characterized bourgeois part,-Poulantzas made httle attempt to clarify the slgnificance of his e de/riocracy. It glrt ese observations, taken in themselves, were by passing observation that ' "reformist" trade unions are now directly no means new, either within or withour the Marxisr problematic, their inserted in the (state) administrative structure'v! Particularly in Iight: systematic location within a Marxist theory of the state was much to be applaudcd. -

Fast and Private Computation of Cardinality of Set Intersection and Union

Fast and Private Computation of Cardinality of Set Intersection and Union Emiliano De Cristofaroy, Paolo Gastiz, and Gene Tsudikz yPARC zUC Irvine Abstract. With massive amounts of electronic information stored, trans- ferred, and shared every day, legitimate needs for sensitive information must be reconciled with natural privacy concerns. This motivates var- ious cryptographic techniques for privacy-preserving information shar- ing, such as Private Set Intersection (PSI) and Private Set Union (PSU). Such techniques involve two parties { client and server { each with a private input set. At the end, client learns the intersection (or union) of the two respective sets, while server learns nothing. However, if desired functionality is private computation of cardinality rather than contents, of set intersection, PSI and PSU protocols are not appropriate, as they yield too much information. In this paper, we design an efficient crypto- graphic protocol for Private Set Intersection Cardinality (PSI-CA) that yields only the size of set intersection, with security in the presence of both semi-honest and malicious adversaries. To the best of our knowl- edge, it is the first protocol that achieves complexities linear in the size of input sets. We then show how the same protocol can be used to pri- vately compute set union cardinality. We also design an extension that supports authorization of client input. 1 Introduction Proliferation of, and growing reliance on, electronic information trigger the increase in the amount of sensitive data stored and processed in cyberspace. Consequently, there is a strong need for efficient cryptographic techniques that allow sharing information with privacy. Among these, Private Set Intersection (PSI) [11, 24, 14, 21, 15, 22, 9, 8, 18], and Private Set Union (PSU) [24, 15, 17, 12, 32] have attracted a lot of attention from the research community. -

1 Measurable Sets

Math 4351, Fall 2018 Chapter 11 in Goldberg 1 Measurable Sets Our goal is to define what is meant by a measurable set E ⊆ [a; b] ⊂ R and a measurable function f :[a; b] ! R. We defined the length of an open set and a closed set, denoted as jGj and jF j, e.g., j[a; b]j = b − a: We will use another notation for complement and the notation in the Goldberg text. Let Ec = [a; b] n E = [a; b] − E. Also, E1 n E2 = E1 − E2: Definitions: Let E ⊆ [a; b]. Outer measure of a set E: m(E) = inffjGj : for all G open and E ⊆ Gg. Inner measure of a set E: m(E) = supfjF j : for all F closed and F ⊆ Eg: 0 ≤ m(E) ≤ m(E). A set E is a measurable set if m(E) = m(E) and the measure of E is denoted as m(E). The symmetric difference of two sets E1 and E2 is defined as E1∆E2 = (E1 − E2) [ (E2 − E1): A set is called an Fσ set (F-sigma set) if it is a union of a countable number of closed sets. A set is called a Gδ set (G-delta set) if it is a countable intersection of open sets. Properties of Measurable Sets on [a; b]: 1. If E1 and E2 are subsets of [a; b] and E1 ⊆ E2, then m(E1) ≤ m(E2) and m(E1) ≤ m(E2). In addition, if E1 and E2 are measurable subsets of [a; b] and E1 ⊆ E2, then m(E1) ≤ m(E2). -

Julia's Efficient Algorithm for Subtyping Unions and Covariant

Julia’s Efficient Algorithm for Subtyping Unions and Covariant Tuples Benjamin Chung Northeastern University, Boston, MA, USA [email protected] Francesco Zappa Nardelli Inria of Paris, Paris, France [email protected] Jan Vitek Northeastern University, Boston, MA, USA Czech Technical University in Prague, Czech Republic [email protected] Abstract The Julia programming language supports multiple dispatch and provides a rich type annotation language to specify method applicability. When multiple methods are applicable for a given call, Julia relies on subtyping between method signatures to pick the correct method to invoke. Julia’s subtyping algorithm is surprisingly complex, and determining whether it is correct remains an open question. In this paper, we focus on one piece of this problem: the interaction between union types and covariant tuples. Previous work normalized unions inside tuples to disjunctive normal form. However, this strategy has two drawbacks: complex type signatures induce space explosion, and interference between normalization and other features of Julia’s type system. In this paper, we describe the algorithm that Julia uses to compute subtyping between tuples and unions – an algorithm that is immune to space explosion and plays well with other features of the language. We prove this algorithm correct and complete against a semantic-subtyping denotational model in Coq. 2012 ACM Subject Classification Theory of computation → Type theory Keywords and phrases Type systems, Subtyping, Union types Digital Object Identifier 10.4230/LIPIcs.ECOOP.2019.24 Category Pearl Supplement Material ECOOP 2019 Artifact Evaluation approved artifact available at https://dx.doi.org/10.4230/DARTS.5.2.8 Acknowledgements The authors thank Jiahao Chen for starting us down the path of understanding Julia, and Jeff Bezanson for coming up with Julia’s subtyping algorithm. -

The Politics of Privatisation and Trade Union Mobilisation: the Electricity Industry in the UK and Argentina

Ghigliani, Pablo The Politics of privatisation and trade union mobilisation: The Electricity industry in the UK and Argentina Ghigliani, P (2010). The Politics of privatisation and trade union mobilisation : The Electricity industry in the UK and Argentina. Bern : Peter Lang. (Trade unions past, present and future ; 3). En Memoria Académica. Disponible en: http://www.memoria.fahce.unlp.edu.ar/libros/pm.646/pm.646.pdf Información adicional en www.memoria.fahce.unlp.edu.ar Esta obra está bajo una Licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial-CompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ To Mariana, who knows why; to Catalina and Teresa, who will; and to Tecla, who won’t. Contents List of Tables ix List of Abbreviations xi Chapter One Introduction 1 Chapter twO Developing the Analytical Framework 7 Chapter three Research Strategies and Methodologies 29 Chapter fOur Privatisation as Counter-Mobilisation 45 Chapter five The Driving-forces of Privatisation in the UK and Argentina 63 Chapter six Comparative Industrial Relations and Mobilisation Theory 75 Chapter seven The Anti-Privatisation Campaigns in the Light of Mobilisation Theory 95 viii Chapter eight List of Tables The Forms of Counter-Mobilisation: The Politics of Money 137 Chapter nine Privatisation and Collective Bargaining 169 Table 1 Detail of Case-Studies 35 Chapter ten Table 2 Distribution of Interviews among Trade Unions 37 Organisational Change, Leadership Styles and Decision-Making 207 Table 3 Main Primary Sources 39 Chapter eleven Table -

Naïve Set Theory Basic Definitions Naïve Set Theory Is the Non-Axiomatic Treatment of Set Theory

Naïve Set Theory Basic Definitions Naïve set theory is the non-axiomatic treatment of set theory. In the axiomatic treatment, which we will only allude to at times, a set is an undefined term. For us however, a set will be thought of as a collection of some (possibly none) objects. These objects are called the members (or elements) of the set. We use the symbol "∈" to indicate membership in a set. Thus, if A is a set and x is one of its members, we write x ∈ A and say "x is an element of A" or "x is in A" or "x is a member of A". Note that "∈" is not the same as the Greek letter "ε" epsilon. Basic Definitions Sets can be described notationally in many ways, but always using the set brackets "{" and "}". If possible, one can just list the elements of the set: A = {1,3, oranges, lions, an old wad of gum} or give an indication of the elements: ℕ = {1,2,3, ... } ℤ = {..., -2,-1,0,1,2, ...} or (most frequently in mathematics) using set-builder notation: S = {x ∈ ℝ | 1 < x ≤ 7 } or {x ∈ ℝ : 1 < x ≤ 7 } which is read as "S is the set of real numbers x, such that x is greater than 1 and less than or equal to 7". In some areas of mathematics sets may be denoted by special notations. For instance, in analysis S would be written (1,7]. Basic Definitions Note that sets do not contain repeated elements. An element is either in or not in a set, never "in the set 5 times" for instance. -

Fast and Private Computation of Cardinality of Set Intersection and Union*

Fast and Private Computation of Cardinality of Set Intersection and Union* Emiliano De Cristofaroy, Paolo Gastiz, Gene Tsudikz yPARC zUC Irvine Abstract In many everyday scenarios, sensitive information must be shared between parties without com- plete mutual trust. Private set operations are particularly useful to enable sharing information with privacy, as they allow two or more parties to jointly compute operations on their sets (e.g., intersec- tion, union, etc.), such that only the minimum required amount of information is disclosed. In the last few years, the research community has proposed a number of secure and efficient techniques for Private Set Intersection (PSI), however, somewhat less explored is the problem of computing the magnitude, rather than the contents, of the intersection – we denote this problem as Private Set In- tersection Cardinality (PSI-CA). This paper explores a few PSI-CA variations and constructs several protocols that are more efficient than the state-of-the-art. 1 Introduction Proliferation of, and growing reliance on, electronic information generate an increasing amount of sensitive data stored and processed in the cyberspace. Consequently, there is a compelling need for efficient cryptographic techniques that allow sharing information while protecting privacy. Among these, Private Set Intersection (PSI) [15, 29, 18, 26, 19, 27, 12, 11, 22], and Private Set Union (PSU) [29, 19, 21, 16, 36] have recently attracted a lot of attention from the research community. In particular, PSI allows one party (client) to compute the intersection of its set with that of another party (server), such that: (i) server does not learn client input, and (ii) client learns no information about server input, beyond the intersection. -

The Soviet Union and the British General Strike of 1926 Alastair Kocho-Williams University of the West of England, Bristol [email protected]

The Soviet Union and the British General Strike of 1926 Alastair Kocho-Williams University of the West of England, Bristol [email protected] This paper addresses the Soviet analysis and response to the British General Strike of 1926 in the light of newly available documents. The recently discovered and published stenograms of Politburo meetings provide new information concerning Soviet politics and the political process. Previously, scholars have had only Soviet official documents and protocols of Politburo meetings, which only detail participants with a brief summary of decisions (vypuski) along with who received these summaries.1 From the protocols, and other sources, scholars were aware that verbatim stenograms existed, some of which were published and distributed to Central Committee members and other party leaders with instructions for them to be returned after they had been read.2 Amongst the ‘lost Politburo stenograms’ is the record of a lengthy, heated, discussion of the ‘lessons of the British General Strike’ on 3 June 1926.3 It is this that the current paper is chiefly concerned with, detailing the Soviet stance towards the General Strike, inconsistency in the Soviet analysis, the extent to which Soviet internal politics was linked to foreign policy, how as senior figures disagreed factions developed around divisions in policy, and the way in which the handling of the international situation formed a strand of the opposition to Stalin and the Politburo majority in 1926.4 The British General Strike ran from 4-12 May 1926. Although it drew British industry to a halt, and hadn’t been planned much in advance, there had been ample warning of a coming labour dispute, of which the British and Soviet Governments were well aware, although the Soviets had concluded that major action was unlikely I am grateful to Paul Gregory and Alexander Vatlin for their assistance in the writing of this paper. -

Legislative Provisions Underlying Trade Unions' Right to Define Their

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ENVIRONMENTAL & SCIENCE EDUCATION 2016, VOL. 11, NO. 10, 3925-3936 OPEN ACCESS Legislative Provisions Underlying Trade Unions’ Right to Define Their Organizational Structure Victoria V. Korobchenkoa, Yury V. Penova and Valery A.Safonova aSaint Petersburg State University, Saint-Petersburg, RUSSIA ABSTRACT The article contains a comparative analysis of constitutional and other legislative provisions that ensure a trade union’s right to define its own administrative structure in European states. The aim of the study is to reveal the management’s problems of European trade unions, declarative and empirical mass-character legislative provisions, which allow to structure trade unions by themselves. The result is that the state should not set forth an exhaustive list of various types of trade unions. The article also examines the authority of trade union associations to define the requirements imposed on their members’ charters. These requirements are argued to comply with the principle of the freedom of association. Moreover, the work reveals that many European legislative provisions are declarated but rarely realized in sphere of inner management. The novelty of the research is the comparative analytic review, basing on the modern local and collective European laws. KEYWORDS ARTICLE HISTORY Trade union, freedom of association, trade union Received 18 March 2016 associations, trade union charter Revised 03 May 2016 Accepted 22 May 2016 Introduction The right to freedom of association is an integral part of a person’s constitutional rights. In labour sphere, workers exercise it and employees either form or join trade unions that serve to protect their rights and interests. According to International Labour Organization’s (ILO) Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work, the freedom of association and effective recognition of the right to collective bargaining belong to the major principles of the labour sphere. -

Trade Unions Are Organisations That Represent People at Work

What do trade i unions do? This is a basic guide to what a trade union is, what we do and why you should join. What is a trade union? Trade unions are organisations that represent people at work. ‘Representing’ 1could mean someone from the union meeting with management on behalf of a member or a group of staff or taking up a problem with your employer for you. Trade unions aim to protect their members. This includes making sure that 2workplaces are safe and that people’s health is not being put at risk through their jobs. It also means legal protection – trade unions usually employ lawyers to make sure that companies and organisations treat their staff in accordance with the law. Trade unions aim to improve their members’ pay and conditions. If a single 3member of staff approaches management because they feel they should be paid more, they are much less likely to be successful than if every member of staff speaks as one through their trade union. Trade unions collectively negotiate better pay and conditions on behalf of their members and, statistically, union members earn more than non-union members. What do trade unions do? l Trade unions speak on behalf of their members. l Trade unions provide members with information, advice and guidance about work-related problems. l Trade unions provide members with a range of services including training, insurance, financial services and legal advice. UCU factsheet 01 What do trade i unions do? l Trade unions bargain with employers to get better pay for members. -

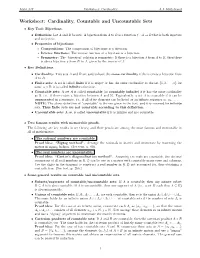

Worksheet: Cardinality, Countable and Uncountable Sets

Math 347 Worksheet: Cardinality A.J. Hildebrand Worksheet: Cardinality, Countable and Uncountable Sets • Key Tool: Bijections. • Definition: Let A and B be sets. A bijection from A to B is a function f : A ! B that is both injective and surjective. • Properties of bijections: ∗ Compositions: The composition of bijections is a bijection. ∗ Inverse functions: The inverse function of a bijection is a bijection. ∗ Symmetry: The \bijection" relation is symmetric: If there is a bijection f from A to B, then there is also a bijection g from B to A, given by the inverse of f. • Key Definitions. • Cardinality: Two sets A and B are said to have the same cardinality if there exists a bijection from A to B. • Finite sets: A set is called finite if it is empty or has the same cardinality as the set f1; 2; : : : ; ng for some n 2 N; it is called infinite otherwise. • Countable sets: A set A is called countable (or countably infinite) if it has the same cardinality as N, i.e., if there exists a bijection between A and N. Equivalently, a set A is countable if it can be enumerated in a sequence, i.e., if all of its elements can be listed as an infinite sequence a1; a2;::: . NOTE: The above definition of \countable" is the one given in the text, and it is reserved for infinite sets. Thus finite sets are not countable according to this definition. • Uncountable sets: A set is called uncountable if it is infinite and not countable. • Two famous results with memorable proofs.