Exaggerated Cartoon Style Motion in Hotel Transylvania

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GLAAD Media Institute Began to Track LGBTQ Characters Who Have a Disability

Studio Responsibility IndexDeadline 2021 STUDIO RESPONSIBILITY INDEX 2021 From the desk of the President & CEO, Sarah Kate Ellis In 2013, GLAAD created the Studio Responsibility Index theatrical release windows and studios are testing different (SRI) to track lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and release models and patterns. queer (LGBTQ) inclusion in major studio films and to drive We know for sure the immense power of the theatrical acceptance and meaningful LGBTQ inclusion. To date, experience. Data proves that audiences crave the return we’ve seen and felt the great impact our TV research has to theaters for that communal experience after more than had and its continued impact, driving creators and industry a year of isolation. Nielsen reports that 63 percent of executives to do more and better. After several years of Americans say they are “very or somewhat” eager to go issuing this study, progress presented itself with the release to a movie theater as soon as possible within three months of outstanding movies like Love, Simon, Blockers, and of COVID restrictions being lifted. May polling from movie Rocketman hitting big screens in recent years, and we remain ticket company Fandango found that 96% of 4,000 users hopeful with the announcements of upcoming queer-inclusive surveyed plan to see “multiple movies” in theaters this movies originally set for theatrical distribution in 2020 and summer with 87% listing “going to the movies” as the top beyond. But no one could have predicted the impact of the slot in their summer plans. And, an April poll from Morning COVID-19 global pandemic, and the ways it would uniquely Consult/The Hollywood Reporter found that over 50 percent disrupt and halt the theatrical distribution business these past of respondents would likely purchase a film ticket within a sixteen months. -

Here Comes Television

September 1997 Vol. 2 No.6 HereHere ComesComes TelevisionTelevision FallFall TVTV PrPrevieweview France’France’ss ExpandingExpanding ChannelsChannels SIGGRAPHSIGGRAPH ReviewReview KorKorea’ea’ss BoomBoom DinnerDinner withwith MTV’MTV’ss AbbyAbby TTerkuhleerkuhle andand CTW’CTW’ss ArleneArlene SherShermanman Table of Contents September 1997 Vol. 2, . No. 6 4 Editor’s Notebook Aah, television, our old friend. What madness the power of a child with a remote control instills in us... 6 Letters: [email protected] TELEVISION 8 A Conversation With:Arlene Sherman and Abby Terkuhle Mo Willems hosts a conversation over dinner with CTW’s Arlene Sherman and MTV’s Abby Terkuhle. What does this unlikely duo have in common? More than you would think! 15 CTW and MTV: Shorts of Influence The impact that CTW and MTV has had on one another, the industry and beyond is the subject of Chris Robinson’s in-depth investigation. 21 Tooning in the Fall Season A new splash of fresh programming is soon to hit the airwaves. In this pivotal year of FCC rulings and vertical integration, let’s see what has been produced. 26 Saturday Morning Bonanza:The New Crop for the Kiddies The incurable, couch potato Martha Day decides what she’s going to watch on Saturday mornings in the U.S. 29 Mushrooms After the Rain: France’s Children’s Channels As a crop of new children’s channels springs up in France, Marie-Agnès Bruneau depicts the new play- ers, in both the satellite and cable arenas, during these tumultuous times. A fierce competition is about to begin... 33 The Korean Animation Explosion Milt Vallas reports on Korea’s growth from humble beginnings to big business. -

Pr-Dvd-Holdings-As-Of-September-18

CALL # LOCATION TITLE AUTHOR BINGE BOX COMEDIES prmnd Comedies binge box (includes Airplane! --Ferris Bueller's Day Off --The First Wives Club --Happy Gilmore)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX CONCERTS AND MUSICIANSprmnd Concerts and musicians binge box (Includes Brad Paisley: Life Amplified Live Tour, Live from WV --Close to You: Remembering the Carpenters --John Sebastian Presents Folk Rewind: My Music --Roy Orbison and Friends: Black and White Night)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX MUSICALS prmnd Musicals binge box (includes Mamma Mia! --Moulin Rouge --Rodgers and Hammerstein's Cinderella [DVD] --West Side Story) [videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX ROMANTIC COMEDIESprmnd Romantic comedies binge box (includes Hitch --P.S. I Love You --The Wedding Date --While You Were Sleeping)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. DVD 001.942 ALI DISC 1-3 prmdv Aliens, abductions & extraordinary sightings [videorecording]. DVD 001.942 BES prmdv Best of ancient aliens [videorecording] / A&E Television Networks History executive producer, Kevin Burns. DVD 004.09 CRE prmdv The creation of the computer [videorecording] / executive producer, Bob Jaffe written and produced by Donald Sellers created by Bruce Nash History channel executive producers, Charlie Maday, Gerald W. Abrams Jaffe Productions Hearst Entertainment Television in association with the History Channel. DVD 133.3 UNE DISC 1-2 prmdv The unexplained [videorecording] / produced by Towers Productions, Inc. for A&E Network executive producer, Michael Cascio. DVD 158.2 WEL prmdv We'll meet again [videorecording] / producers, Simon Harries [and three others] director, Ashok Prasad [and five others]. DVD 158.2 WEL prmdv We'll meet again. Season 2 [videorecording] / director, Luc Tremoulet producer, Page Shepherd. -

Netent Announces Jumanji As Its Latest Branded Game Deal in Collaboration with Sony Pictures Entertainment

PRESS RELEASE 19th January, 2018 NetEnt announces Jumanji as its latest branded game deal in collaboration with Sony Pictures Entertainment. NetEnt, the leading provider of digital gaming solutions, has signed an agreement with Sony Pictures Consumer Products to launch a video slot machine game based on the original Jumanji film. The new Jumanji game, which will be released later this year, follows the recent launch of the holiday blockbuster film ‘Jumanji: Welcome to the Jungle’. The current film has resonated with critics and audiences alike around the globe having delivered more than $676 million in global box office. Henrik Fagerlund, Chief Product Officer of NetEnt, said: “Being able to secure a deal for another high-profile title showcases the moves we’re making in diversifying our roster of games.” Jumanji is a great addition to NetEnt’s renowned branded games portfolio alongside the likes of Planet of the Apes™, Guns N’ Roses™ and Motörhead Video Slot™. “The original Jumanji movie, which debuted in 1995, remains a moviegoer favorite and continues to demonstrate its cross-generational appeal more than 20 years later! Also, with the recent release of the new film, the Jumanji brand is more popular than ever. We’re excited for the game launch in 2018, continued Fagerlund.” Attendees at ICE can visit NetEnt’s stand (N3-242) to get a sneak peek of the game. NetEnt will be continuing the tradition at ICE unveiling another branded title at 15:00 on Tuesday, 6th February. For additional information please contact: [email protected] NetEnt AB (publ) is a leading digital entertainment company, providing premium gaming solutions to the world’s most successful online casino operators. -

Available Papers and Transcripts from the Society for Animation Studies (SAS) Annual Conferences

SAS Conference papers Pagina 1 NIAf - Available papers and transcripts from the Society for Animation Studies (SAS) annual conferences 1st SAS conference 1989, University of California, Los Angeles, USA Author (Origin) Title Forum Pages Copies Summary Notes Allan, Robin (InterTheatre, European Influences on Disney: The Formative Disney 20 N.A. See: Allan, 1991. Published as part of A Reader in Animation United Kingdom) Years Before Snow White Studies (1997), edited by Jayne Pilling, titled: "European Influences on Early Disney Feature Films". Kaufman, J.B. (Wichita) Norm Ferguson and the Latin American Films of Disney 8 N.A. In the years 1941-43, Walt Disney and his animation team made three Published as part of A Reader in Animation Walt Disney trips through South America, to get inspiration for their next films. Studies (1997), edited by Jayne Pilling. Norm Ferguson, the unit producer for the films, made hundreds of photo's and several people made home video's, thanks to which Kaufman can reconstruct the journey and its complications. The feature films that were made as a result of the trip are Saludos Amigos (1942) and The Three Caballero's (1944). Moritz, William (California Walter Ruttmann, Viking Eggeling: Restoring the Aspects of 7 N.A. Hans Richter always claimed he was the first to make absolute Published as part of A Reader in Animation Institute of the Arts) Esthetics of Early Experimental Animation independent and animations, but he neglected Walther Ruttmann's Opus no. 1 (1921). Studies (1997), edited by Jayne Pilling, titled institutional filmmaking Viking Eggeling had made some attempts as well, that culminated in "Restoring the Aesthetics of Early Abstract the crude Diagonal Symphony in 1923 . -

PREVIEWS Plus!

READ ABOUT THESE ITEMS AND MORE AT PREVIEWSworld.com When a new item’s so hot it can’t wait to be solicited in the next issue of PREVIEWS, you’ll find it here in PREVIEWS Plus! Here’s your last chance to order some of the hottest comics, toys and merchandise before they come to your comic shop! Order these items from your retailer by MONDAY, OCTOBER 24 PREMIER PUBLISHERS MARVEL COMICS .com world DEADPOOL: BACK IN BLACK #1 DEATH OF X #1 SECOND PRINTING SECOND PRINTING AARON KUDER VARIANT SALVA ESPIN VARIANT (W) Jeff Lemire, Charles Soule (W) Cullen Bunn (A/CA) Salva Espin (A/CA) Aaron Kuder AMAZING SPIDER-MAN #19 CAGE #1 SECOND PRINTING During 1984’s Secret Wars, Deadpool What happened eight months ago that SECOND PRINTING GENNDY TARTAKOVSKY VARIANT was introduced to an alien symbiote who set the Inhumans and X-Men on a collision ALEX ROSS VARIANT (W) Genndy Tartakovsky PREVIEWS went on to become Spider-Man’s black course? Find out here! The Inhumans (W) Dan Slott, Christos Gage (A) Genndy Tartakovsky, Stephen DeStefano costume and, eventually, Venom. Okay, travel to Japan where one of the Terrigen (A) Giuseppe Camuncoli & Various (CA) Genndy Tartakovsky okay, maybe that really happened in Clouds creates a shocking new Inhuman. (CA) Alex Ross From the award-winning creator of Deadpool’s Secret Secret Wars. Point The X-Men travel to Muir Island where the Before “Dead No More”... Someone Dexter’s Laboratory, Samurai Jack, and is, did you know that after Spider-Man second Terrigen Cloud causes something in the Amazing Spider-Man’s orbit dies. -

The Uses of Animation 1

The Uses of Animation 1 1 The Uses of Animation ANIMATION Animation is the process of making the illusion of motion and change by means of the rapid display of a sequence of static images that minimally differ from each other. The illusion—as in motion pictures in general—is thought to rely on the phi phenomenon. Animators are artists who specialize in the creation of animation. Animation can be recorded with either analogue media, a flip book, motion picture film, video tape,digital media, including formats with animated GIF, Flash animation and digital video. To display animation, a digital camera, computer, or projector are used along with new technologies that are produced. Animation creation methods include the traditional animation creation method and those involving stop motion animation of two and three-dimensional objects, paper cutouts, puppets and clay figures. Images are displayed in a rapid succession, usually 24, 25, 30, or 60 frames per second. THE MOST COMMON USES OF ANIMATION Cartoons The most common use of animation, and perhaps the origin of it, is cartoons. Cartoons appear all the time on television and the cinema and can be used for entertainment, advertising, 2 Aspects of Animation: Steps to Learn Animated Cartoons presentations and many more applications that are only limited by the imagination of the designer. The most important factor about making cartoons on a computer is reusability and flexibility. The system that will actually do the animation needs to be such that all the actions that are going to be performed can be repeated easily, without much fuss from the side of the animator. -

Please Continue on Back If Needed!

DARK HORSE DC: VERTIGO MARVEL CONT. ANGEL AMERICAN VAMPIRE DEADPOOL BPRD ASTRO CITY FANTASTIC FOUR BUFFY FABLES GHOST RIDER CONAN THE BARBARIAN FAIREST GUARDIANS OF THE GALAXY HELLBOY FBP HAWKEYE MASSIVE SANDMAN INDESTRUCTIBLE HULK "THE" STAR WARS TRILLIUM IRON MAN STAR WARS - Brian Wood Classic UNWRITTEN IRON PATRIOT STAR WARS LEGACY WAKE LOKI STAR WARS DARK TIMES IDW MAGNETO DC COMICS BLACK DYNAMITE MIGHTY AVENGERS ACTION COMICS DOCTOR WHO MIRACLEMAN ADVENTURES OF SUPERMAN G.I. JOE MOON KNIGHT ALL-STAR WESTERN G.I. JOE REAL AMERICAN HERO MS MARVEL ANIMAL MAN G.I. JOE SPECIAL MISSIONS NEW AVENGERS AQUAMAN GHOSTBUSTERS NEW WARRIORS BATGIRL GODZILLA NOVA BATMAN JUDGE DREDD ORIGIN II BATMAN / SUPERMAN MY LITTLE PONY PUNISHER BATMAN / SUPERMAN POWERPUFF GIRLS SAVAGE WOLVERINE BATMAN & ---- SAMURAI JACK SECRET AVENGERS BATMAN 66 STAR TREK SHE HULK BATMAN BEYOND UNIVERSE TEENAGE MNT CLASSICS SILVER SURFER BATMAN LIL GOTHAM TEENAGE MUTANT NINJA TURTLES SUPERIOR FOES OF SPIDERMAN BATMAN: THE DARK KNIGHT TRANSFORMERS More Than Meets Eye SUPERIOR SPIDERMAN BATWING TRANSFORMERS Regeneration One SUPERIOR SPIDERMAN TEAM-UP BATWOMAN TRANSFORMERS Robots in Disguise THOR GOD OF THUNDER BIRDS OF PREY IMAGE THUNDERBOLTS CATWOMAN ALEX & ADA UNCANNY AVENGERS CONSTANTINE BEDLAM UNCANNY X-MEN DETECTIVE COMICS BLACK SCIENCE WOLVERINE EARTH 2 BOUNCE WOLVERINE & THE X-MEN FLASH CHEW X-FORCE GREEN ARROW EAST OF WEST X-MEN GREEN LANTERN ELEPHANTMENT X-MEN LEGACY -

Aug CUSTOMER ORDER FORM

OrdErS PREVIEWS world.com duE th 18 aug 2013 aug COMIC THE SHOP’S PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CATALOG CUSTOMER ORDER FORM CUSTOMER 601 7 Aug13 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 7/3/2013 3:05:51 PM Available only DEADPOOL: “TACO ENTHUSIAST” from your local BLUE T-SHIRT comic shop! Preorder now! THE WALKING DEAD: STREET FIGHTER: DOCTOR WHO: “THE DIXON BROS.” “THE STREETS” “DON’T BLINK” GLOW ZIP HOODIE RED T-SHIRT IN THE DARK T-SHIRT Preorder now! Preorder now! Preorder now 8 Aug 13 COF Apparel Shirt Ad.indd 1 7/3/2013 10:34:19 AM PrETTY DEADLY #1 ImAgE COmICS THE SHAOLIN COWBOY #1 DArk HOrSE COmICS THE SANDmAN: OVErTUrE #1 DC COmICS / VErTIgO VELVET #1 ELFQUEST SPECIAL: ImAgE COmICS THE FINAL QUEST DArk HOrSE COmICS SAmUrAI JACk #1 IDW PUBLISHINg SUPErmAN/WONDEr mArVEL kNIgHTS: WOmAN #1 SPIDEr-mAN #1 DC COmICS mArVEL COmICS Aug13 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 7/3/2013 9:04:01 AM Featured Items COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS The Fox #1 l ARCHIE COMICS Uber Volume 1 Enhanced HC l AVATAR PRESS Imagine Agents #1 l BOOM! STUDIOS The Shadow Now #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Cryptozoic Man #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Peanuts Every Sunday 1952-1955 HC l FANTAGRAPHICS BOOKS Battling Boy GN/HC l :01 FIRST SECOND Letter 44 #1 l ONI PRESS 1 1 Ben 10 Omniverse Volume 1: Ghost Ship GN l PERFECT SQUARE X-O Manowar Deluxe HC l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT Miss Peregrine’s Home For Peculiar Children HC l YEN PRESS BOOKS The Superman Files HC l COMICS Doctor Who 50th Anniversary Anthology l DOCTOR WHO Doctor Who: The Vault: Treasures from the First 50 Years HC l DOCTOR WHO Dc Comics Guide To Creating Comics Sc l HOW-TO Star Trek: Mr. -

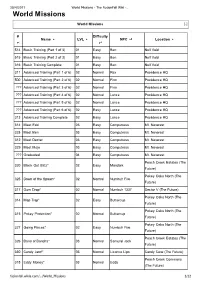

World Missions - the Fusionfall Wiki -… World Missions

20/4/2011 World Missions - The FusionFall Wiki -… World Missions World Missions [-] # Difficulty Name LVL NPC Location 514 Basic Training (Part 1 of 3) 01 Easy Ben Null Void 515 Basic Training (Part 2 of 3) 01 Easy Ben Null Void 316 Basic Training Complete 01 Easy Ben Null Void 311 Advanced Training (Part 1 of 6) 02 Normal Rex Providence HQ 500 Advanced Training (Part 2 of 6) 02 Normal Finn Providence HQ ??? Advanced Training (Part 3 of 6) 02 Normal Finn Providence HQ ??? Advanced Training (Part 4 of 6) 02 Normal Lance Providence HQ ??? Advanced Training (Part 5 of 6) 02 Normal Lance Providence HQ ??? Advanced Training (Part 6 of 6) 02 Easy Lance Providence HQ 313 Advanced Training Complete 02 Easy Lance Providence HQ 314 Meet Edd 03 Easy Computress Mt. Neverest 328 Meet Ben 03 Easy Computress Mt. Neverest 312 Meet Dexter 03 Easy Computress Mt. Neverest 329 Meet Mojo 03 Easy Computress Mt. Neverest ??? Graduated 04 Easy Computress Mt. Neverest Peach Creek Estates (The 320 Black Out Blitz* 02 Easy Mandark Future) Pokey Oaks North (The 325 Dawn of the Spawn* 02 Normal Numbuh Five Future) 317 Gum Drop* 02 Normal Numbuh 1337 Sector V (The Future) Pokey Oaks North (The 314 Map Trap* 02 Easy Buttercup Future) Pokey Oaks North (The 315 Pokey Protection* 02 Normal Buttercup Future) Pokey Oaks North (The 327 Going Places* 02 Easy Numbuh Five Future) Peach Creek Estates (The 326 Band of Bandits* 03 Normal Samurai Jack Future) 330 Candy Jarrr!* 03 Normal Licorice Lips Candy Cove (The Future) Peach Creek Commons 318 Eddy Money* 03 Normal Eddy (The -

Cultural Stereotypes: from Dracula's Myth to Contemporary Diasporic Productions

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2006 Cultural Stereotypes: From Dracula's Myth to Contemporary Diasporic Productions Ileana F. Popa Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/1345 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cultural Stereotypes: From Dracula's Myth to Contemporary Diasporic Productions A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at Virginia Commonwealth University. Ileana Florentina Popa BA, University of Bucharest, February 1991 MA, Virginia Commonwealth University, May 2006 Director: Marcel Cornis-Pope, Chair, Department of English Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond, Virginia May 2006 Table of Contents Page Abstract.. ...............................................................................................vi Chapter I. About Stereotypes and Stereotyping. Definitions, Categories, Examples ..............................................................................1 a. Ethnic stereotypes.. ........................................................................3 b. Racial stereotypes. -

Movies & Languages 2013-2014 Hotel Transylvania

Movies & Languages 2013-2014 Hotel Transylvania About the movie (subtitled version) DIRECTOR Genndy Tartakovsky YEAR / COUNTRY 2012 U.S.A GENRE Comedy, Animation ACTORS Adam Sandler, Andy Samberg, Steve Buscemi, Selena Gomez PLOT The Hotel Transylvania is Dracula's lavish five-stake resort he built for his beloved wife Martha and their daughter Mavis. Monsters and their families are invited to Mavis's 118th birthday party where they can live it up, free from meddling with the human world. But here's a little known fact about Dracula: he is not only the Prince of Darkness; he is also a dad. Over-protective of his teenage daughter, Mavis, Dracula fabricates tales of elaborate dangers to dissuade her adventurous spirit. As a haven for Mavis, he opens the Hotel Transylvania, where his daughter and some of the world's most famous monsters – Frankenstein and his bride, the Mummy, the Invisible Man, a family of werewolves, gremlins and more – can kick back in safety and peace. For Drac, catering to all of these legendary monsters is no problem but his world could come crashing down when one ordinary guy discovers the hotel and takes a shine to Mavis. LANGUAGE Simple English spoken in Eastern European, American and French accents GRAMMAR INDEPENDENT ELEMENTS/INTERJECTIONS Introductory - Oh! ah! alas! Ha ha, ha! hollo! hurrah! pshaw! etc. express sudden bursts of feeling. As they have no grammatical relation to any other word in the sentence, we say that they are independent. Words belonging to other parts of speech become interjections when used as mere exclamations: What! are you going? Well! you surprise me Other words besides interjections may be used independently: Come on boys Well, we will try it Now, that is strange Why, this looks right There is reason in this Boys simply arrests the attention of the persons addressed.