Recent Judgments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Household Water Usage Community Awareness Regarding

Original Article DOI: http://doi.org/10.4038/jmj.v32i1.90 The household water usage Community awareness regarding water pollution and factors associated with it among adult residents in MOH area, Uduvil 1Rajeev G , 2Murali V 1 RDHS Jaffna,2 Ministry of Health Abstract Introduction Introduction: Water pollution is a one of the Water is the driving force of nature and most public health burdens and the consumption of important natural resource that permeates all contaminated water has adverse health effects and aspects of the life on Earth. It is essential for even affects fetal development. The objective was human health and contributes to the sustainability to describe the household water usage pattern, of ecosystems. Safe water access and adequate community awareness of water pollution and sanitation are two basic determinants of good health factors associated with it among adult residents in (1). Both of these are important to protect people MOH area, Uduvil. from water related diseases like diarrhoeal diseases and typhoid (2). Method: A descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted on a community-based sample Clean drinking water is important for overall health of 817 adult residents with multi stage cluster and plays a substantial role in health of children sampling method. The data was collected by and their survival. Giving access to safe water is an interviewer administered questionnaire. one of the most effective ways to promote health Statistically significance for selected factors and and reduce poverty. All have the right to access awareness were analyzed with chi square and enough, continuous, safe, physically accessible, Mann-Whitney U test. -

Documents in Support of Their Respective Positions

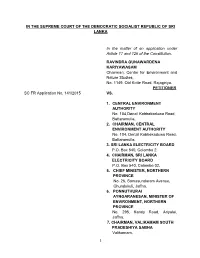

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA In the matter of an application under Article 17 and 126 of the Constitution. RAVINDRA GUNAWARDENA KARIYAWASAM Chairman, Centre for Environment and Nature Studies, No. 1149, Old Kotte Road, Rajagiriya. PETITIONER SC FR Application No. 141/2015 VS. 1. CENTRAL ENVIRONMENT AUTHORITY No. 104,Denzil Kobbekaduwa Road, Battaramulla. 2. CHAIRMAN, CENTRAL ENVIRONMENT AUTHORITY No. 104, Denzil Kobbekaduwa Road, Battaramulla. 3. SRI LANKA ELECTRICITY BOARD P.O. Box 540, Colombo 2. 4. CHAIRMAN, SRI LANKA ELECTRICITY BOARD P.O. Box 540, Colombo 02. 5. CHIEF MINISTER, NORTHERN PROVINCE No. 26, Somasundaram Avenue, Chundukuli, Jaffna. 6. PONNUTHURAI AYNGARANESAN, MINISTER OF ENVIRONMENT, NORTHERN PROVINCE No. 295, Kandy Road, Ariyalai, Jaffna. 7. CHAIRMAN, VALIKAMAM SOUTH PRADESHIYA SABHA Valikamam. 1 8. NORTHERN POWER COMPANY (PVT) LTD. No. 29, Castle Street, Colombo 10. 9. HON. ATTORNEY GENERAL Attorney General‟s Department, Colombo 12. 10. BOARD OF INVESTMENT OF SRI LANKA Level 26, West Tower, World Trade Center, Colombo 1. 11. NATIONAL WATER SUPPLY AND DRAINAGE BOARD P.O. Box 14, Galle Road, Mt. Lavinia. RESPONDENTS 1. DR. RAJALINGAM SIVASANGAR Chunnakam East, Chunnakam. 2. SINNATHURAI SIVAMAINTHAN Chunnakam East, Chunnakam. 3. SIVASAKTHIVEL SIVARATHEES Chunnakam East, Chunnakam. ADDED RESPONDENTS BEFORE: Priyantha Jayawardena, PC, J. Prasanna Jayawardena, PC, J. L.T.B. Dehideniya, J. COUNSEL: Nuwan Bopage with Chathura Weththasinghe for the Petitioner. Dr. Avanti Perera, SSC for the 1st to 4th, 9th, 10th and 11th Respondents. Dr. K.Kanag-Isvaran,PC with L.Jeyakumar instructed by M/S Sinnadurai Sundaralingam and Balendra for the 5th Respondent. Dinal Phillips,PC with Nalin Dissanayake and Pulasthi Hewamanne instructed by Ms. -

Download the Conference Book

Colombo Conclave 2020 Colombo Conclave 2020 Published in December, 2020 © Institute of National Security Studies Sri Lanka ISBN 978-624-5534-00-5 Edited by Udesika Jayasekara, Ruwanthi Jayasekara All rights reserved. No portion of the contents maybe reproduced or reprinted, in any form, without the written permission of the Publisher. Opinions expressed in the articles published in the Colombo Conclave 2020 are those of the authors/editors and do not necessarily reflect the view of the INSSL. However, the responsibility for accuracy of the statements made therein rests with the authors. Published by Institute of National Security Studies Sri Lanka 8th Floor, ‘SUHURUPAYA’, Battarmulla, Sri Lanka. TEL: +94112879087, EMAIL: [email protected] WEB: www.insssl.lk Printed by BANDARA TRADINGINT (PVT) LTD No. 106, Main Road, Battaramulla, Sri Lanka TEL: +9411 22883867 / +94760341703, EMAIL: [email protected] CONTENTS CONCEPT PAPER 1 INAUGURAL SESSION Biography 5 Admiral (Prof.) Jayanath Colombage RSP, VSV, USP, rcds, psc MSc (DS), MA (IS), Dip in IR, Dip in CR, FNI (Lond) Director General, Institute of National Security Studies Sri Lanka and Secretary to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs Welcome Remarks 6 Admiral (Prof.) Jayanath Colombage RSP, VSV, USP, rcds, psc MSc (DS), MA (IS), Dip in IR, Dip in CR, FNI (Lond) Director General, Institute of National Security Studies Sri Lanka and Secretary to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs Biography 9 Maj Gen (Retd) Kamal Gunaratne WWV RWP RSP USP ndc psc MPhil Secretary, Ministry of Defence Keynote Address 10 Maj Gen (Retd) Kamal Gunaratne WWV RWP RSP USP ndc psc MPhil Secretary, Ministry of Defence SESSION 1 - REDEFINING THREATS TO NATIONAL SECURITY Biography 15 Amb. -

No Law Or Ordinance Is Mightier Than Understanding" - Plato

JSA News Letter 2021 Volume 01 Exco 2021 Office Bearers Editorial President First time in our life, we are much delighted when people say we Mr. Prasanna Alwis are negative; that is when we hear our polymerase chain reaction or PCR Magistrate, Nugegoda. test result. Covid -19 has made many significant changes in our day-to-day life. It transformed our lifestyle and made us more accommodating. Was it Vice Presidents possible for a lawyer or litigant or even a judge to sit in the open court with Mr. Udesh Ranathunge a face mask a few years ago? It was a sign of remonstration and amount to Magistrate, contempt or misconduct. Now the law insists everyone wear a face mask Mount Lavinia as a necessity for protection. A sign of misconduct has become the sign of Mr. Priyantha Liyanage protection. Therefore, no tradition or custom is indispensable when it is Magistrate, Fort. not helpful to human existence. I believe that a plain reading of a law passed by the legislature will Secretary not be sufficient for understanding its nature. When law evolves from Miss. Nilupulee Lankapura its previous position to respond to the new challenge, the stakeholders Magistrate, Homagama. of the administration of the justice system should be in the position to Assistant Secretary receive it with understanding. For that, personal development skills such Mrs. Chathurika Silva as legal knowledge and comprehension in the legal analysis are paramount. Additional District Judge, A judicial officer who is willing to take part in the process of a meaningful Colombo. administration of justice has to enhance his/her legal consciousness by a comparative legal analysis of how the law operates in our legal system and Treasurer of how it functions in the other jurisdictions. -

Ceylon Electricity Board Long Term Generation Expansion Plan

CEYLON ELECTRICITY BOARD LONG TERM GENERATION EXPANSION PLAN 2013-2032 Transmission and Generation Planning Branch Transmission Division Ceylon Electricity Board Sri Lanka October 2013 Long Term Generation Expansion Planning Studies 2013- 2032 Compiled and prepared by The Generation Planning Unit Transmission and Generation Planning Branch Ceylon Electricity Board, Sri Lanka Long-term generation expansion planning studies are carried out every two years by the Transmission & Generation Planning Branch of the Ceylon Electricity Board, Sri Lanka and this report is a bi-annual publication based on the results of the latest expansion planning studies. The data used in this study and the results of the study, which are published in this report, are intended purely for this purpose. Price Rs. 3000.00 © Ceylon Electricity Board, Sri Lanka, 2013 Note: Extracts from this book should not be reproduced without the approval of General Manager – CEB Foreword The ‘Report on Long Term Generation Expansion Planning Studies 2013-2032’, presents the results of the latest expansion planning studies conducted by the Transmission and Generation Planning Branch of the Ceylon Electricity Board for the planning period 2013- 2032, and replaces the last of these reports prepared in April 2011. This report, gives a comprehensive view of the existing generating system, future electricity demand and future power generation options in addition to the expansion study results. The latest available data were used in the study. The Planning Team wishes to express their gratitude to all those who have assisted in preparing the report. We would welcome suggestions, comments and criticism for the improvement of this publication. -

70806 CEA Terms It

www.themorning.lk Late City VOL 01 | NO 13 | Rs. 30.00 { WEDNESDAY } WEDNESDAY, FEBRUARY 10, 2021 GODS, DEVAS, WI TOUR TO BE YAKAS, AND DEMONS REARRANGED AS A IN POP ART LIMITED-OVER SERIES? ECT: HANGING FROM MANUFACTURING A GEOPOLITICAL COACHES: EVALUATION NOOSE COMMITTEE APPOINTED »SEE PAGE 11 »SEE PAGE 5 »SEE PAGE 7 »SEE PAGE 16 ALLEGED ‘DEFORESTATION’ OF VEDDA LANDS Vaccine gap may CEA terms it ‘a political problem’ become 12 weeks BY PAMODI WARAVITA – cultivates maize on lands yesterday (9), CEA Chairman z Time between 1st and z Immunisation Advisory z Second vaccination The Central Environmental that are also in reality the Siripala Amarasinghe said Authority (CEA) is of the dwelling places of the veddas, that the CEA has given 2nd doses 4 weeks now Group mulls lengthening essential view that if the Mahaweli the country’s indigenous first permission to the Mahaweli BY DINITHA RATHNAYAKE “The National Immunisation National Institute of Infectious Diseases Authority – to which it nation people, then such Authority to cultivate maize The National Immunisation Technical Advisory Group Technical Advisory Group is discussing Hospital (IDH) senior consultant has granted permission to would constitute a “political in lands that do not have a is considering extending the gap between the first and the matter. A second vaccination is physician Dr. Ananda Wijewickrama cultivate maize in lands that problem”. forest cover. second doses of Covid-19 vaccines from four weeks to absolutely essential because it triggers told The Morning yesterday (9). do not have a forest cover Speaking to The Morning Contd. on page 2 12 weeks, The Morning learnt. -

Decisions of the Supreme Court on Parliamentary Bills

DECISIONS OF THE SUPREME COURT ON PARLIAMENTARY BILLS 2014 - 2015 VOLUME XII Published by the Parliament Secretariat, Sri Jayewardenepura Kotte November - 2016 PRINTED AT THE DEPARTMENT OF GOVERNMENT PRINTING, SRI LANKA. Price : Rs. 364.00 Postage : Rs. 90.00 DECISIONS OF THE SUPREME COURT OF THE REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA UNDER ARTICLES 120, 121 AND 122 OF THE CONSTITUTION OF THE DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA FOR THE YEARS 2014 AND 2015 i ii 2 - PL 10020 - 100 (2016/06) CONTENTS Title of the Bill Page No. 2014 Assistance to and Protection of Victims of Crime and Witnesses 03 2015 Appropriation (Amendment ) 13 National Authority on Tobacco and Alcohol (Amendment) 15 National Medicines Regulatory Authority 21 Nineteenth Amendment to the Constitution 26 Penal Code (Amendment) 40 Code of Criminal Procedure (Amendment) 40 iii iv DECISIONS OF THE SUPREME COURT ON PARLIAMENTARY BILLS 2014 (2) D I G E S T Subject Determination Page No. No. ASSISTANCE TO AND PROTECTION OF VICTIMS 01/2014 to 03 - 07 OF CRIME AND WITNESSES 06/2014 to provide for the setting out of rights and entitlements of victims of crime and witnesses and the protection and promotion of such rights and entitlements; to give effect to appropriate international norms, standards and best practices relating to the protection of victims of crime and witnesses; the establishment of the national authority for the protection of victims of crime and witnesses; constitution of a board of management; the victims of crime and witnesses assistance and protection division of the Sri Lanka Police Department; payment of compensation to victims of crime; establishment of the victims of crime and witnesses assistance and protection fund and for matters connected therewith or incidental thereto. -

Oil Spill Contamination of Ground Water in Chunnakam Aquifer, Jaffna, Srilanka S

Oil spill contamination of Ground water in Chunnakam Aquifer, Jaffna, Srilanka S. Saravanan1 1National Water Supply and Drainage Board ABSTRACT The Chunnakam aquifer has high capacity and contains acceptable quality water for drinking and other usages. Water supplies are generated from this area. Fuel smell had been continuously observed in Chunnakam water intake site. The intake site is located very close to the Chunnakam fossil fuel power station, and on analysis, the intake well and the adjacent wells showed oil contamination. A research study was carried out during the peri- od November 2013 to August 2014. The total number of 150 wells was analyzed, of these 109 (73%) wells have shown higher oil level than the Srilankan standard 614(1983) of 1.0 mg/l, 07 (4%) wells were under the limit and 34 wells (23%) were not contaminated with oil and grease. From the analysis the oil and grease contamination was observed within 1.5 km surrounding of the power station. The high oil and grease concentration layers were observed in the surrounding of the Chunnakam power station area. Keywords Oil and Grease, Chunnakam, Ground water, Wells, Power station 1. Introduction Agriculture is practiced to a larger extent in this area. Therefore the aquifer is exposed to number of severe The Jaffna peninsula is located in the Northern vulnerabilities such as over-extraction of groundwater tip of Srilanka. It covers an area of 1,012.01 excessive fertilizer usage, and other forms of pollution by km2, including inland waters with a population anthropogenic activities. (Feasibility study, March 2006) of 607,158.(Statistical Hand book, Jaffna 2013) Fossil fuel power plants use chemical energy, In Jaffna, four main groundwater aquifers are avail- which is stored in fossil fuels such as coal, fuel oil, able for water consumption based on the water capac- natural gas or oil shale. -

Covid-19 a Refining Local Cases Total Cases 3,388 Process Deaths Recovered Active Cases 130 13 3,245 Rs

DEVELOPING AN ENERGY HUB COVID-19 A REFINING LOCAL CASES TOTAL CASES 3,388 PROCESS DEATHS RECOVERED ACTIVE CASES 130 13 3,245 RS. 70.00 PAGES 88 / SECTIONS 7 VOL. 03 – NO. 01 SUNDAY, OCTOBER 4, 2020 CASES AROUND THE WORLD RECOVERED TOTAL CASES 25,732,161 DECISIVE IMF STILL DEATHS WEEK AHEAD CONSIDERING 34,579,033 1,029,177 FOR 20A RFI REQUEST THE ABOVE STATISTICS ARE CONFIRMED UP UNTIL 8.10 P.M. ON 02 OCTOBER 2020 »SEE PAGES 8 & 9 »SEE BUSINESS PAGE 1 »SEE PAGE 4 Japan’s tit for LRT tat z Decides to hold transmission and distribution project z Concerned about SL debt situation and financial policy BY MAHEESHA MUDUGAMUWA Greater Colombo Transmission bilateral co-operation are until the above mentioned situations and Distribution Loss Reduction treated with gravity by Japan. are improved,” the letter stated. In what is likely a reaction to the Sri Lankan Government’s Project Phase II towards the The policies included the “JICA shall follow the Government stance on the Colombo Light Rail Transit (LRT) Project, the appraisal stage”. request for a debt moratorium of Japan’s policies but we are willing Japanese Government has decided to put on hold the Greater The letter, signed by JICA South by the GoSL to Japan, the to restart the formulation process Colombo Transmission and Distribution Loss Reduction Asia Department South Asia Division construction of a new power regarding the project once the Project Phase II. 3 Director Naoaki Miyata, stated that plant, and the project for Government of Japan confirms the Japan is concerned about the current establishing an LRT system situations are improved.” In a letter written to the Director was seen by The Sunday Morning, debt situation of the Government in Colombo. -

Covid-19 Sliding Local Cases Total Cases Towards 3,345 a Grave Deaths Recovered Disaster Active Cases 174 13 3,158 Rs

Illegal and hazardous constructions COVID-19 SLIDING LOCAL CASES TOTAL CASES TOWARDS 3,345 A GRAVE DEATHS RECOVERED DISASTER ACTIVE CASES 174 13 3,158 RS. 70.00 PAGES 88 / SECTIONS 7 VOL. 02 – NO. 53 SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 27, 2020 CASES AROUND THE WORLD RECOVERED TOTAL CASES 22,092,196 DORMANT 20A STIRS UP A DEATHS OIL PIPELINE HORNET’S NEST IN AND 30,407,457 951,473 RESURFACES OUTSIDE GOVERNMENT THE ABOVE STATISTICS ARE CONFIRMED UP UNTIL 7.20 P.M. ON 25 SEPTEMBER 2020 »SEE BUSINESS PAGE 1 »SEE PAGES 8 & 9 »SEE PAGE 5 LRT project still alive z Transport Ministry yet z Cabinet decision z Current cost lower to act on letter required to terminate than initial estimate BY MAHEESHA MUDUGAMUWA this is a costly project and we have to think about the country’s The Colombo Light Rail Transit (LRT) Project is yet economic situation after the to be terminated despite the request made by impact of Covid. Therefore, the President’s Secretary Dr. P.B Jayasundara as per the President’s Secretary requested directives of President Gotabaya Rajapaksa last me to think about this project week, The Sunday Morning learnt. and take proper decisions. The decision of course cannot be When contacted by The Sunday project had been approved by the made at the ministry level. It Morning, Ministry of Transport Cabinet, it should be terminated should be done by the Cabinet Secretary Monti Ranatunga by the Cabinet, he said. of Ministers because this project stressed that the directives to “There is an evaluation started based on the cabinet terminate the project should committee, and the committee’s decision.” come from the Cabinet; as the recommendation is that maybe Contd. -

Statistical Digest 2011

LECO ELECTRICITY SALES GENERAL STATISTICS LENGTH OF TRANSMISSION AND DISTRIBUTION LINES IN km. C.E.B. TARIFF - EFFECTIVE FROM 01-01-2011 TO 31-12-2011 % % DOMESTIC - Unit Rate Fixed Charge SALES BY TARIFF IN GWh. CONSUMER ACCOUNTS BY TARIFF Units 2010 2011* Change 2010 2011 Change (for each 30 days billing period) % % Population (Mid Year) Thous. 20,653 20,869 1.0 % Block 1 - First 30 units @ Rs 3.00 per unit + Rs. 30.00 2010 2011 Change 2010 2011 Change 220 kV Route Length O.H. 483 483 0.0 % GNP at Current Prices Rs.m. 5,534,327 6,470,617 16.9 % Block 2 - 31 - 60 units @ Rs 4.70 per unit + Rs. 60.00 132 kV Route Length O.H. 1,714 1,724 0.6 % Chunnakam Domestic 503 538 7.0% 404,495 412,858 2.1% GNP at Constant (2002) Prices Rs.m. 2,612,603 2,832,318 8.4 % Block 3 - 61 - 90 units @ Rs 7.50 per unit + Rs. 90.00 GDP at Current Prices Rs.m. 5,604,104 6,542,663 16.7 % 132 kV Route Length U.G. 41 50 21.0 % Block 4 - 91 - 120 units @ Rs 21.00 per unit + Rs. 315.00 Transmission Religious 7 8 9.7% 2,287 2,325 1.7% Block 5 - 121 - 180 units @ Rs 24.00 per unit + Rs. 315.00 GDP at Constant (2002) Prices Rs.m. 2,645,542 2,863,854 8.3 % 33 kV Route Length O.H. 24,370 25,257 3.6 % General Total 321 367 14.3% 64,514 67,634 4.8% Block 6 - Above 180 units @ Rs 36.00 per unit + Rs. -

Decisions of the Supreme Court on Parliamentary Bills (2018)

DECISIONS OF THE SUPREME COURT OF THE REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA UNDER ARTICLES 120 AND 121 OF THE CONSTITUTION OF THE DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA FOR THE YEAR 2018 ( i ) ( ii ) CONTENTS Title of the Bill Page No. Active Liability Management 5 Judicature (Amendment) 17 National Audit 32 Land (Restrictions on Alienation) (Amendment) 39 Mutual Assistance in Criminal Matters (Amendment) 43 Office for Reparations 51 Medical (Amendment) 60 Twentieth Amendment to the Constitution 67 Counter Terrorism 83 -------- ( iii ) (iv) DECISIONS OF THE SUPREME COURT ON PARLIAMENTARY BILLS 2018 ( v ) Digest of the Decisions of the Supreme Court on Parliamentary Bills - 2018 D I G E S T Determination Page Subject No. No. Active Liability Management to authorise the raising of loans in or outside Sri Lanka for 1/2018 to the purpose of Active Liability Management to improve 6/2018 public debt management in Sri Lanka and to make provisions for matters connected therewith or incidental thereto. The Supreme Court determined that the provisions of the Bill are not inconsistent with the Constitution. Judicature (Amendment) 07/2018 to 13/2018 to amend the Judicature Act, No. 2 of 1978 The Supreme Court determined that Section 12A (1) of the Bill is inconsistent with the Article 154P (3)(a) of the Constitution and an amendment is required to be made to the Constitution to give effect to the Section 12A (1) of the Bill. This requires the Bill to be passed by a two- third majority. However, if the jurisdiction is conferred on the High Court of Provinces under Article 154P (3)(C) like in Act No.